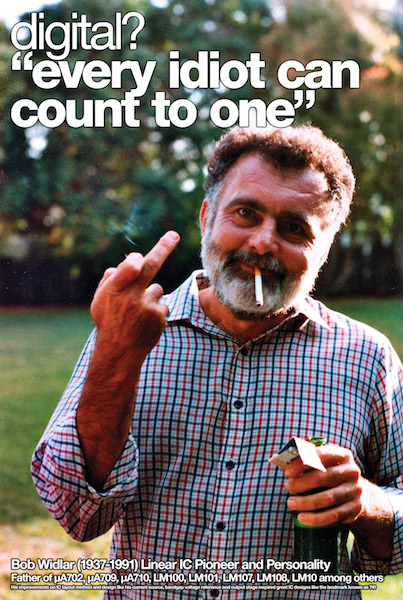

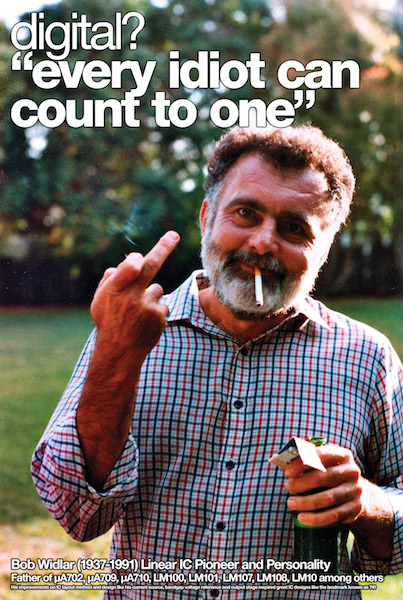

Legendary Robert Vidlar. Paranoid and hermit

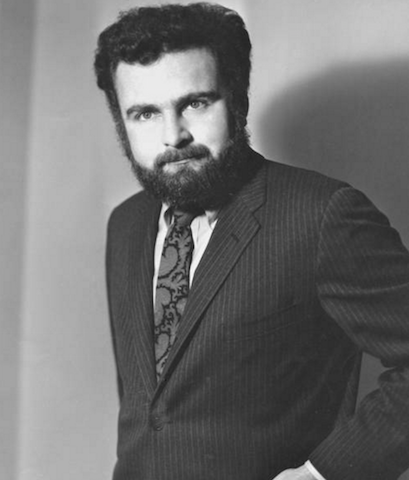

The name of Robert Vidlar became known during the time of the so-called first semiconductor boom, he took an active part in many research works related to operational amplifiers. Surely we can say that he was one of the important figures in the early startups of Silicon Valley. Startups like Fairchild and National Semiconductor were not without its breakthrough ideas and developments. Paranoid and recluse, at times simply intolerable type, lover of indulging in alcoholic drinks ... and a brilliant engineer - Bob Vidlar! From the words of colleagues, Bob could ruffle and irritate anyone, but they had to endure his antics, since electronics in those times was an area of “creative singles”, and Robert was one such loner.

Who has not heard of such a process as "visualization"? The process is the destruction of defective parts and non-working prototypes with nothing more than a hammer. Vidlar was very intolerant of such “troubles”, therefore, armed with a hammer, ruthlessly sent them to the dump: “... the ax hung in his office in a prominent place and also served as an anti-stealer: Vidlar chopped off the stitched pieces of paper. very much: Vidlar made copies of everything that he happened to read. " In an interesting way, Bob struggled "with loud sounds," which he simply could not bear. Personally, in his office, the engineer installed a device that, in case the visitor raised his voice or started shouting at Widlar, issued a shrill whistle. "The Hassler" - so colleagues have called this device (from the English. Pester).

')

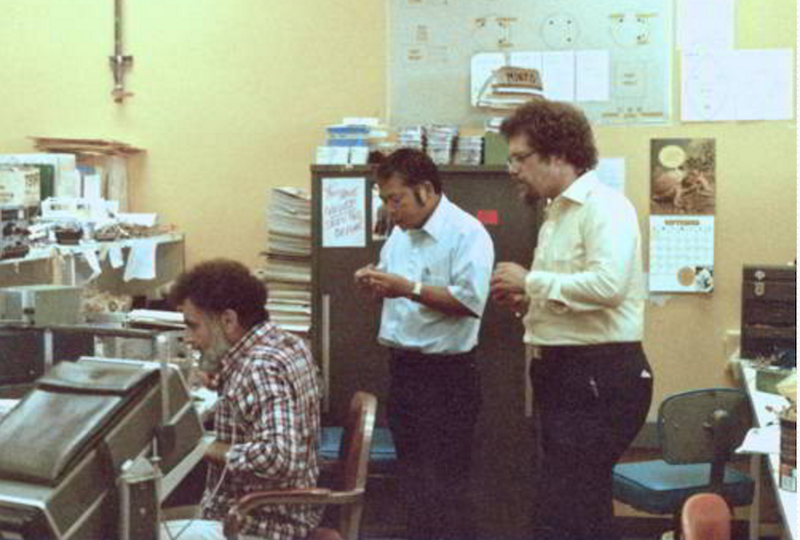

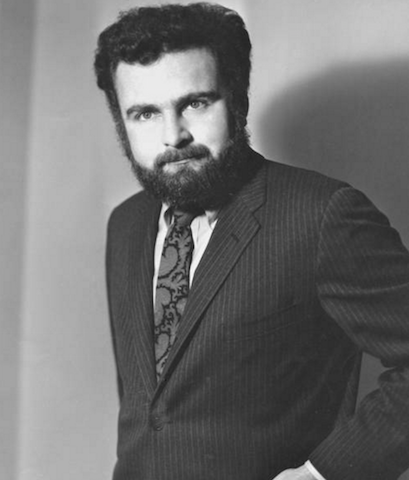

In the 60s, young specialist Robert Vidlar became the head of the linear integrated circuit department at Fairchild . He was a pioneer developer of semiconductor operational amplifiers. Operational amplifiers were used to perform operations on analog signals (addition, multiplication, integration). OA remained the most important components of almost any electronic device associated with analog signals. Vidlaru first came up with the idea that you should not save on elements, because the cost of the chip will not change due to the number of transistors on it will be placed, or it will be 10 pieces, or 100 pieces. And ... Bob created an operational amplifier with characteristics unattainable for discrete circuitry. In 1966, Bob quit his job with Fairchild and began working at National Semiconductors, it was here that Vidlar created an OU line, whose names begin with LM.

Bob Widlar - treasonable genius

From 1961 to 1963, Fairchild was one of the most prominent companies in business history. Many scientific and business talents “in great concentration” were gathered here ... “having achieved success in the business world, they asked themselves: what would happen if they could stay together and rule the world of semiconductors by more than one generation? ..” But now all the same about Bob Vidlar.

"... The door opened. The first person to go through it was Bob Widlar, a traitorous genius. Looking at his past drunkenness, fights and erratic behavior, one cannot help but notice that Widlar was one of the most creative minds in the history of technology. Its strong the side were linear devices - non-digital circuits like amplifiers, which were the last best canvases of prominent artists in electronics. "

Fairchild's golden years are not only years of development of technologies of historical significance, but also crazy parties, parties, fun to bewilderment: "... there were endless drunken parties in the next Wagon Wheel saloon where workers of the company were seduced, families were destroyed, hostility was maintained, and in time - workers were lured away by competitors. " Frequently such was the design genius Robert Widlar. He was considered the craziest of the inhabitants of Silicon Valley. He could in anger because of an unsuccessful invention to go out and cut down the trees that were planted for the improvement of the environment. Napodbiter Vidlar could take part in fights to the blood with competitors at the demonstration site of the industry exhibition.

Bob was very worried about his freedom, even more than his linear devices. Restrictions in anything were not for his nature. The shortage of money was also a kind of restriction, which was the reason that in 1966, Vidlar left Fairchild Semiconductor with the small semiconductor company National Semiconductor. This love of his was shown to them when he had to go through the dismissal procedure and fill out a six-page list of questions about dismissal. On each page in large block letters Vidlar wrote - I WANT TO BECOME REAL and modestly signed at the end of the "X".

Little biography

Robert Vidlar was born on November 30, 1937, in the city of Cleveland (Ohio). His family did not feel material needs, his father - with German roots, his mother - Czech. Walter Vidlar, of the influential German lineage, was a self-taught radio engineer, published in the professional and local press, was an expert in frequency modulation. Already at the age of 15, Bob Jr., following in the footsteps of his father, started repairing televisions and successfully mastered the basics of radio engineering. At the age of 45, Bob's father died of a massive heart attack.

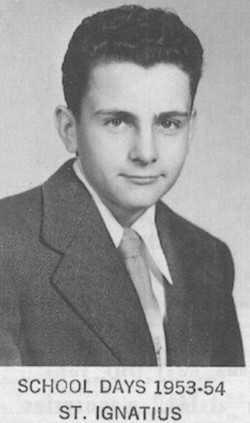

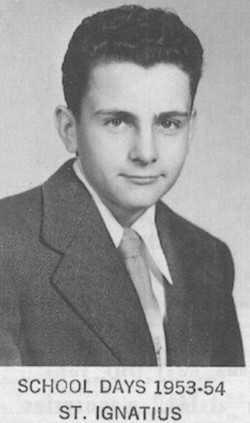

Robert Vidlar took the place of his father in a large family, he had to earn a living, initially he was engaged in cleaning, and later repairing radio equipment. After graduating from the Jesuit school of St. Ignatius in Cleveland, he worked for a year as a technician at the firm where his father once worked, and in 1958 he volunteered for the US Air Force and served two full years as an electronic equipment instructor based in Colorado. In 1960, the Air Force Training Department published his first book in an edition of 100 copies. It was a tutorial on semiconductor devices.

In 1962, Bob graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder. In 1961, Robert retired from the Air Force and got a job as an engineer at the instrument engineering company Ball Brothers Research Corporation. The company, working on NASA orbital station control devices, first encountered the problem of the radiation resistance of transistors. In order to understand, Amelco was forced to meet with the leaders (the only company at that time that produced a transistor with certified radiation resistance). Jean Ernie and Sheldon Roberts were the last founders of Fairchild Semiconductor. After this meeting, Vidlar decided to be in the center of events concerning electronics, that is, to begin work on semiconductor production. Fairchild Semiconductor violated its professional ethics and lured Robert from her client.

At the end of 1963, Bob moved to the southwest of the USA, to California (Mountain View), in Silicon Valley. As mentioned earlier, there he began working at Fairchild and headed the department of linear integrated circuits.

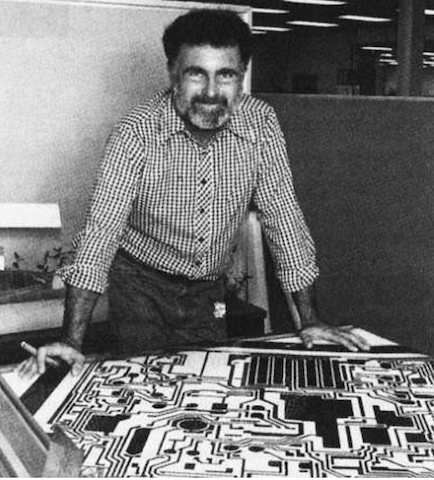

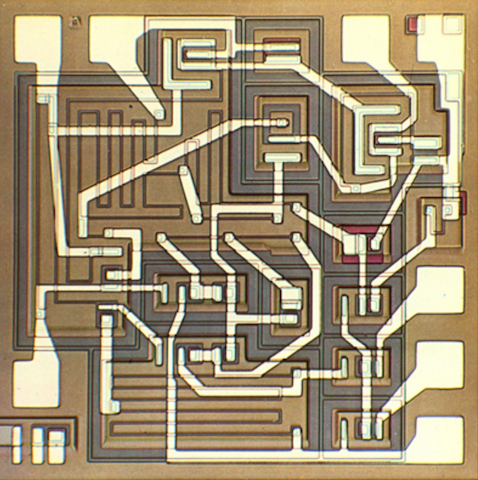

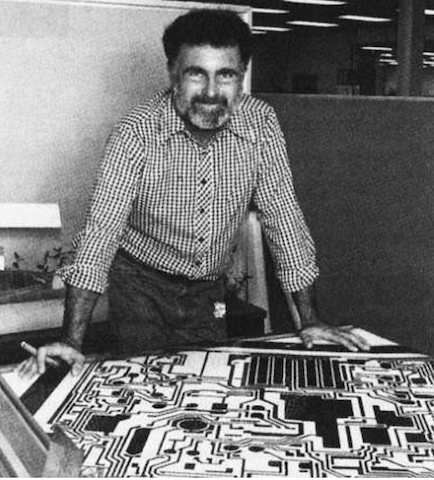

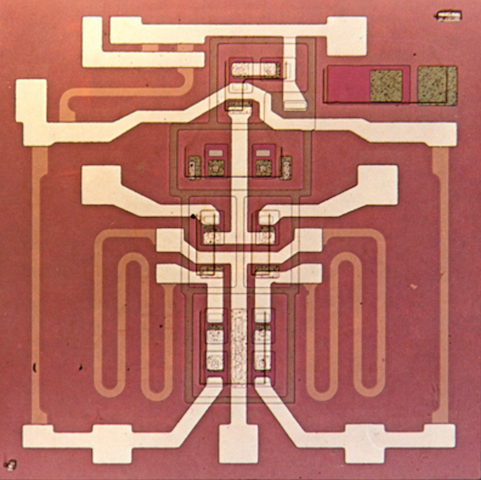

At 26, Robert Vidlar developed his first monolithic OU chip, mA702. Its price was 300 dollars apiece. Later, Bob improved the circuit, and the light saw a new operational amplifier, which was designated as mA709, was sold such an opamp at $ 70 apiece. After such an economically successful development, Vidlar asked for a salary increase. After refusal, he quit. During the three years of work in this company, Vidlar developed and introduced into production his world-wide “linear series”: m702 (141), m709 (1531), m710 (5212), m711 (5211), m723, m726. In general, from 10 to 100 million pieces were released for each position.

m700

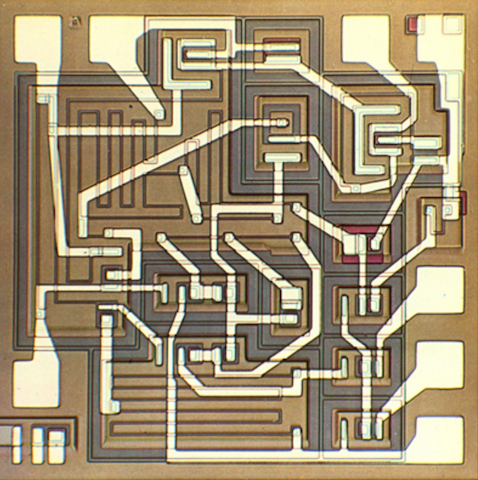

m709

He went to work at the company National Semiconductor, where Vidlar was very pleased, because even then he was considered the person who initiated the development of analog chips.

In 1966, he became one of the founders of the National Semiconductors Linear IC Group (abbreviated NS) - not only a purely semiconductor company, but also a specialized linear (Santa Clara, California). In 1967, Vidlar developed an even more advanced op amp for National Semiconductor, which became known as the LM101. Widlar took up the position of director of promising schemes in NS and took up the development of next-generation chips: LM101 (153UD2), LM108 (104UD14), LM118 (140UD10,) LM102, LM109, LM111 (521CA3).

An interesting fact . Fairchild was worried about the sudden rival Bob Widlar, so in the company's research lab, young employee David Fullagar began to study the LM101 Shelter thoroughly. He found several flaws in the chip. In order to avoid frequency distortions, developers had to hang an external capacitor to the IC, and the input stage of some instances of the microcircuit was very sensitive to external noise - this was due to the spread of parameters during manufacturing.

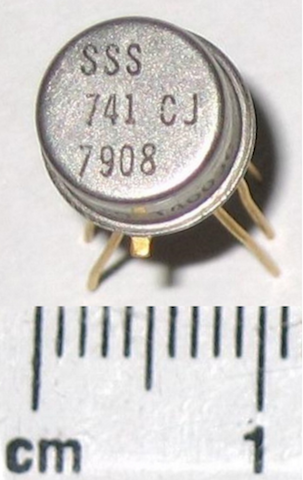

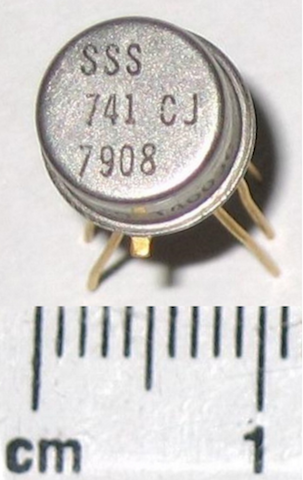

Fullagar took it upon himself to develop OU. He expanded the manufacturing process tolerances by installing a 30 picofarad capacitor inside the chip. The input stage has been improved by adding a pair of transistors to the circuit. This addition has improved the repeatability of the chips. As a result, a new mA741 chip was developed, which has become the standard for operational amplifiers. This chip, its variants were sold in hundreds of millions of pieces. For $ 300 it was possible to buy almost a thousand 741 chips.

LM101 (153UD2)

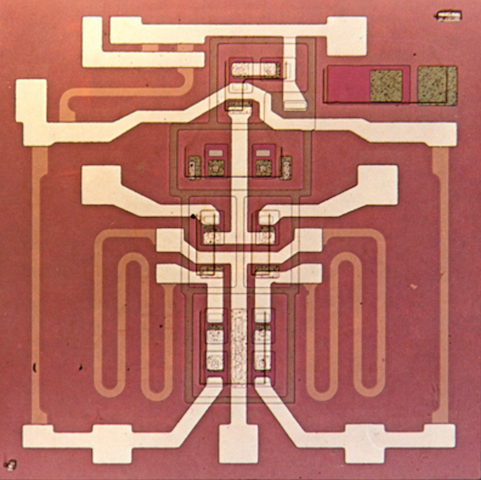

Vidlar developed the LM101 operational amplifier, which became the first second-generation opamp, the LM101 block diagram became the basis for all subsequent universal operational amplifiers. Active loads provided the LM101 with large gains for each stage, the input emitter repeaters loaded on the differential cascade on pnp transistors in turn provided a wide range of permissible input voltages and low bias currents.

DC gain reached 500,000 (50,000-100,000 for first-generation amplifiers). The input stage was protected from high voltages, the output stage had full short circuit protection. Two stages of voltage amplification were used, the so-called two-stage scheme. The LM101 was stable with a single external correction capacitance of just 30pF.

It was here that Vidlar made an error when he did not try to pack this capacitance on the crystal of the operational amplifier. A year later, as mentioned above, this gap was filled by competitors from Fairchild, and the A741 was released; roughly speaking, clone LM101 with internal frequency correction. This easy-to-use microchip has won the universal OU market.

A741

In the following years (1968 - 1969), Vidlar and Telbert developed and debugged new active devices in production: super-beta transistors , a multi-collector bipolar transistor and an epitaxial field-effect transistor

In 1969, Vidlar developed the first super-beta transistor operational amplifier, which was named the LM108 .

At the end of 1969, a new operational accelerator was released, the functional equivalent of the LM101 on the new element base - LM101A .

In 1970, the LM101 version with built-in correction capacity, the LM107 , was developed.

Telbert's six-hour process technology later allowed both pinch resistors, field-effect transistors, super-beta transistors, and side pnp transistors with a current gain of over 100 to be implemented on a single chip. The number of transistors serving current sources LM101A was reduced through the use of multicolumn pnp transistors. The input impedance of the operational accelerator, which did not use composite transistors at the input, for the first time exceeded the level of 1 MΩ.

From 1963 to 1971, Robert Vidlar wrote more than 50 articles on linear topics, where he described the “insides” of the OS, methods of their application. Vidlar patented integrated structures: side pnp, band-gap supporting element, super beta transistor, low voltage (1.2 V) amplifiers and others.

National Semiconductor released the Vllar LM100 , which was the first integral voltage regulator in history. The LM100 stabilized voltages from 2 to 30V with a cumulative error in the military temperature range (55 to 125C) not more than 1%. The reference voltage source the 6.3V Zener, the regulating element is a relatively low-power composite transistor, so in practice the LM100 was used not as a complete stabilizer, but as an external power transistor control circuit. The demand surpassed the most istichnye expectations. "

In 1970, the LM109 was produced - the world's first integrated three-output voltage regulator for 5V, which became the direct predecessor of the A7805 . Its creation was preceded by the requirement of customers to combine a control circuit and a power transistor on a single chip, while packing a full-fledged stabilizer into a case with three terminals: input, output, and common. Vidlar stated that such an arrangement of a power transistor and a control circuit on a single chip is not only permissible, but also greatly simplifies the overheating protection circuit. Such a stabilizer has already been implemented in silicon and was ready for serial production.

The LM109 microcircuit differed from the LM100 in limiting values of current and power, in its ease of use, the source of the reference voltage in an opamp was no longer served by a Zener diode, but by the Vglar bandgap .

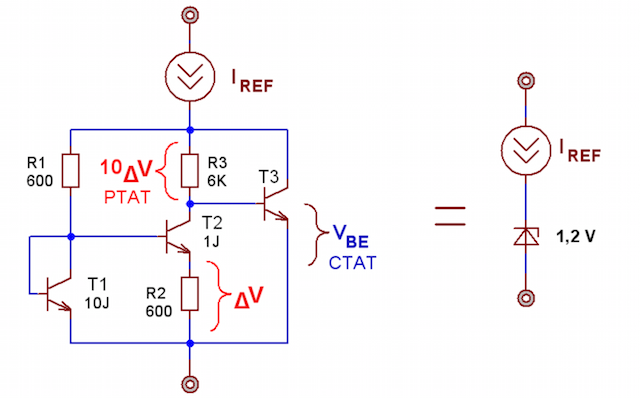

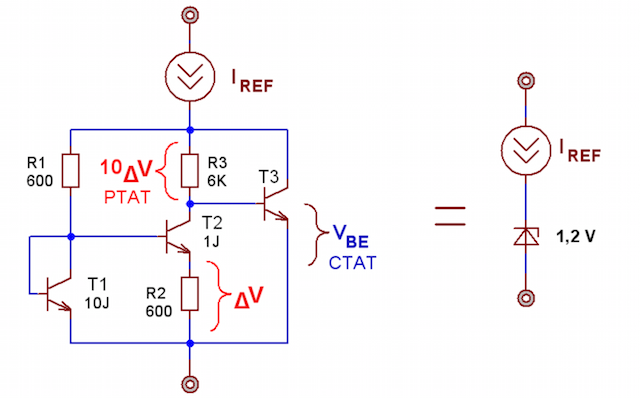

The simplest implementation scheme for bandgap Vidlar

Bandgap Vidlar - transistor voltage reference, approximately equal to the width of the forbidden zone of silicon (about 1.2V). Vidlar was the first to design the first practical bandgap principle (which was formulated back in 1964 by David Hilbiber). LM109 was the first chip with integrated bandgap.

In 1971, the LM113 was developed, which was a two-pin precision diode in the Vidlar bandgap. Replacing the high-voltage (about 6V) Zener diode with a low-voltage (1.2V) bandgap made it possible to create cost-effective stabilizers for low output voltages (3.3V, 2.5B and below) and amplifiers with low-voltage power (from 1.1V).

At the beginning of the 70 Robert Vidlar disappeared. In 1971, the legend moved to Mexico, then he began working in his new company Linear Technology Corp (abbreviated LTC). It was rumored that in Mexico, the tax press was "softer" than in the United States.

Many call Robert Widlar - Steve Jobs 70 years. He was brilliant, but at the same time paranoid. His passion for a glass is often mentioned on the pages of his biography. But, surprisingly, he was unusually efficient, he could work on the microcircuit for days, months ... and only then he went into the booze. He was sick of work, not feeling tired - worked.

Although Robert came to electronics before the spread of computer simulation of electronic circuits, until the end of his life he refused to use them.

Owning the traditional skills of mathematical analysis, he could, for several hours, without interruption, be engaged in calculations, and then without a single mistake, put the results on paper. Vidlar wanted to control everything; the entire product development cycle, including sales, was to be under its control. Developing schemes, wrote to them all the technical documentation, up to a detailed guide to their use.

After Bob retired from Fairchild, the problem of alcohol was even worse. He spent the night in bars, drunk to a semi-conscious state.

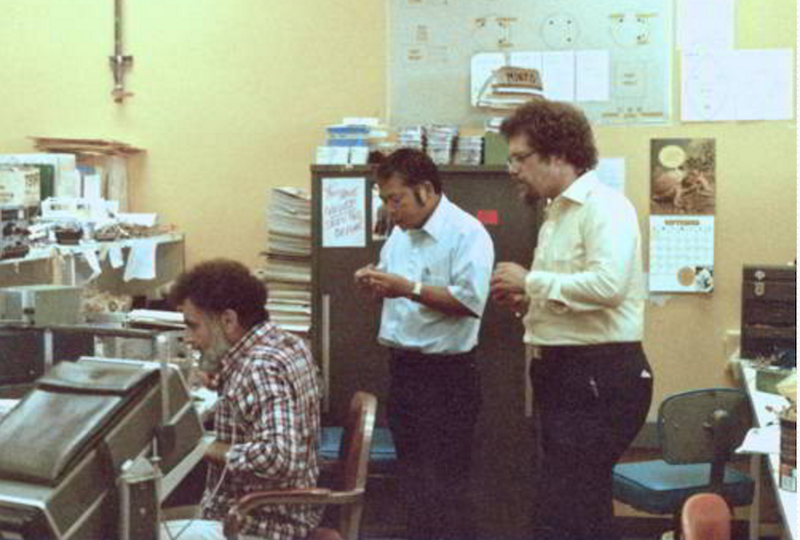

He was cocky, in one of the night showdowns, after drinking, he “invited” Mike Scott (the future president of Apple) to go out to talk, this conversation ended in a knockout of Widlar. Later, Vidlar began to drink continuously, his antics covered and even rescued him from arrest. Here is what Spork recalled about Widlar's drunkenness: "... He drank too much, and I had to endure it. I had no choice: this guy, for a while, was National Semiconductor. Once, at a seminar in Paris, we gathered about 1,200 engineers from We made a mistake in France and Belgium by opening access to the bar at lunchtime - in France it was so accepted.

And so he began to drink gin, neat, with large glasses, and I realized - to be in trouble. After lunch, he returned to the hall with a full glass of gin. I got to Peter Sprague, who was sitting next to Vidlar, and said to him: Peter, get rid of this gin before Vidlar falls under the table. Poor Peter sacrificed himself and drank everything to the bottom. At the beginning of his speech, Vidlar habitually reached for his glass, but it was empty. Vidlar shouted that he would not utter a word until a glass was poured over him. There was no choice, I had to pour him a full glass, and he continued. He could barely stand on his feet, but what is interesting is that even in such a state he fascinated the listener. And then I took him to the hotel by subway. He stood, reeling, at the very edge of the platform, and I stood at the back, ready to grab him. If he had fallen on the rails, the company would have died with him. "

The legendary sheep of Robert Vidlar

At the end of 1970, Vidlar decided to leave National Semiconductor.The company, in order to save, refused to mow lawns in front of the main building ... Bob decided to make a gift to the company). For $ 60, he bought a sheep from a familiar farmer and, being unhappy with the view of an overgrown meadow (where he parked his two-seater Mercedes), let the animal “trim” the lawn. Vidlar invited a San Jose News reporter for publicity to write an article with a comment from Bob about how "... a sheep has left many gardeners without work, but it can not only cut it, it can also fertilize!"

A sheep was stolen at night. There are many legends and myths around this story. Someone said that Vidlar himself took a sheep and drank it in one of the bars, according to another version, the sheep was not a sheep at all, but a goat, or, better still, a goat.

The last 20 years of his life, Vidlar worked under contracts with National Semiconductor and was engaged in some kind of uncertain development of production processes. From 1971 to the end of 1989, he issued only 8 patents for inventions. After the dismissal, he got a million dollars in his hands, went to Mexico and settled in Puerto Vallarta.

At thirty-three, Vidlar, finally got the freedom she dreamed of. He did not work on a permanent job. Vidlar continued to work alone on complex circuit design issues, occasionally lecturing in the USA.

In 1974, Spord managed to persuade Widlar to return to National Semiconductor. Vidlar became an independent company consultant, while living in Mexico. From 1974 to 1991, Widlar developed dozens of new projects for National Semiconductor.

In 1976, the LM10 was developed . This is a micropowerful operational amplifier and a reference voltage source, which is capable of operating at a supply voltage from 1.1 to 40 V, the first operational amplifier fully capable of operating from a single 1.4 V electroplating cell.

After the LM11 was developed , a precision bipolar OU which was designed for electrometric measurements.

In 1987, the first powerful (10 A, 80 W) LM12 operational amplifier was launched .

On February 27, 1991, the body of Widlar was found in the vicinity of Puerto Vallarta. There was a version that Bob died of a heart attack while jogging on the beach. But Bob Pease rejected this version, as usually Vidlar ran in the mountains, perhaps the attack caught him as he went down the slope, fell and died. The fact remains, the legendary personality was gone at the age of 53 years. As Vidlar himself assured, recently he settled down, even started a permanent relationship with a woman, stopped drinking alcohol. But predisposition to heart disease and lifestyle in young years, alas, did not go "without a trace."

The unpredictability, genius of Robert Vidlar mixed with his love for alcohol, hermit lifestyle made him, even during his lifetime, a legend.

Who has not heard of such a process as "visualization"? The process is the destruction of defective parts and non-working prototypes with nothing more than a hammer. Vidlar was very intolerant of such “troubles”, therefore, armed with a hammer, ruthlessly sent them to the dump: “... the ax hung in his office in a prominent place and also served as an anti-stealer: Vidlar chopped off the stitched pieces of paper. very much: Vidlar made copies of everything that he happened to read. " In an interesting way, Bob struggled "with loud sounds," which he simply could not bear. Personally, in his office, the engineer installed a device that, in case the visitor raised his voice or started shouting at Widlar, issued a shrill whistle. "The Hassler" - so colleagues have called this device (from the English. Pester).

')

In the 60s, young specialist Robert Vidlar became the head of the linear integrated circuit department at Fairchild . He was a pioneer developer of semiconductor operational amplifiers. Operational amplifiers were used to perform operations on analog signals (addition, multiplication, integration). OA remained the most important components of almost any electronic device associated with analog signals. Vidlaru first came up with the idea that you should not save on elements, because the cost of the chip will not change due to the number of transistors on it will be placed, or it will be 10 pieces, or 100 pieces. And ... Bob created an operational amplifier with characteristics unattainable for discrete circuitry. In 1966, Bob quit his job with Fairchild and began working at National Semiconductors, it was here that Vidlar created an OU line, whose names begin with LM.

Bob Widlar - treasonable genius

From 1961 to 1963, Fairchild was one of the most prominent companies in business history. Many scientific and business talents “in great concentration” were gathered here ... “having achieved success in the business world, they asked themselves: what would happen if they could stay together and rule the world of semiconductors by more than one generation? ..” But now all the same about Bob Vidlar.

"... The door opened. The first person to go through it was Bob Widlar, a traitorous genius. Looking at his past drunkenness, fights and erratic behavior, one cannot help but notice that Widlar was one of the most creative minds in the history of technology. Its strong the side were linear devices - non-digital circuits like amplifiers, which were the last best canvases of prominent artists in electronics. "

Fairchild's golden years are not only years of development of technologies of historical significance, but also crazy parties, parties, fun to bewilderment: "... there were endless drunken parties in the next Wagon Wheel saloon where workers of the company were seduced, families were destroyed, hostility was maintained, and in time - workers were lured away by competitors. " Frequently such was the design genius Robert Widlar. He was considered the craziest of the inhabitants of Silicon Valley. He could in anger because of an unsuccessful invention to go out and cut down the trees that were planted for the improvement of the environment. Napodbiter Vidlar could take part in fights to the blood with competitors at the demonstration site of the industry exhibition.

Bob was very worried about his freedom, even more than his linear devices. Restrictions in anything were not for his nature. The shortage of money was also a kind of restriction, which was the reason that in 1966, Vidlar left Fairchild Semiconductor with the small semiconductor company National Semiconductor. This love of his was shown to them when he had to go through the dismissal procedure and fill out a six-page list of questions about dismissal. On each page in large block letters Vidlar wrote - I WANT TO BECOME REAL and modestly signed at the end of the "X".

Little biography

Robert Vidlar was born on November 30, 1937, in the city of Cleveland (Ohio). His family did not feel material needs, his father - with German roots, his mother - Czech. Walter Vidlar, of the influential German lineage, was a self-taught radio engineer, published in the professional and local press, was an expert in frequency modulation. Already at the age of 15, Bob Jr., following in the footsteps of his father, started repairing televisions and successfully mastered the basics of radio engineering. At the age of 45, Bob's father died of a massive heart attack.

Robert Vidlar took the place of his father in a large family, he had to earn a living, initially he was engaged in cleaning, and later repairing radio equipment. After graduating from the Jesuit school of St. Ignatius in Cleveland, he worked for a year as a technician at the firm where his father once worked, and in 1958 he volunteered for the US Air Force and served two full years as an electronic equipment instructor based in Colorado. In 1960, the Air Force Training Department published his first book in an edition of 100 copies. It was a tutorial on semiconductor devices.

In 1962, Bob graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder. In 1961, Robert retired from the Air Force and got a job as an engineer at the instrument engineering company Ball Brothers Research Corporation. The company, working on NASA orbital station control devices, first encountered the problem of the radiation resistance of transistors. In order to understand, Amelco was forced to meet with the leaders (the only company at that time that produced a transistor with certified radiation resistance). Jean Ernie and Sheldon Roberts were the last founders of Fairchild Semiconductor. After this meeting, Vidlar decided to be in the center of events concerning electronics, that is, to begin work on semiconductor production. Fairchild Semiconductor violated its professional ethics and lured Robert from her client.

At the end of 1963, Bob moved to the southwest of the USA, to California (Mountain View), in Silicon Valley. As mentioned earlier, there he began working at Fairchild and headed the department of linear integrated circuits.

At 26, Robert Vidlar developed his first monolithic OU chip, mA702. Its price was 300 dollars apiece. Later, Bob improved the circuit, and the light saw a new operational amplifier, which was designated as mA709, was sold such an opamp at $ 70 apiece. After such an economically successful development, Vidlar asked for a salary increase. After refusal, he quit. During the three years of work in this company, Vidlar developed and introduced into production his world-wide “linear series”: m702 (141), m709 (1531), m710 (5212), m711 (5211), m723, m726. In general, from 10 to 100 million pieces were released for each position.

m700

m709

He went to work at the company National Semiconductor, where Vidlar was very pleased, because even then he was considered the person who initiated the development of analog chips.

In 1966, he became one of the founders of the National Semiconductors Linear IC Group (abbreviated NS) - not only a purely semiconductor company, but also a specialized linear (Santa Clara, California). In 1967, Vidlar developed an even more advanced op amp for National Semiconductor, which became known as the LM101. Widlar took up the position of director of promising schemes in NS and took up the development of next-generation chips: LM101 (153UD2), LM108 (104UD14), LM118 (140UD10,) LM102, LM109, LM111 (521CA3).

An interesting fact . Fairchild was worried about the sudden rival Bob Widlar, so in the company's research lab, young employee David Fullagar began to study the LM101 Shelter thoroughly. He found several flaws in the chip. In order to avoid frequency distortions, developers had to hang an external capacitor to the IC, and the input stage of some instances of the microcircuit was very sensitive to external noise - this was due to the spread of parameters during manufacturing.

Fullagar took it upon himself to develop OU. He expanded the manufacturing process tolerances by installing a 30 picofarad capacitor inside the chip. The input stage has been improved by adding a pair of transistors to the circuit. This addition has improved the repeatability of the chips. As a result, a new mA741 chip was developed, which has become the standard for operational amplifiers. This chip, its variants were sold in hundreds of millions of pieces. For $ 300 it was possible to buy almost a thousand 741 chips.

LM101 (153UD2)

Vidlar developed the LM101 operational amplifier, which became the first second-generation opamp, the LM101 block diagram became the basis for all subsequent universal operational amplifiers. Active loads provided the LM101 with large gains for each stage, the input emitter repeaters loaded on the differential cascade on pnp transistors in turn provided a wide range of permissible input voltages and low bias currents.

DC gain reached 500,000 (50,000-100,000 for first-generation amplifiers). The input stage was protected from high voltages, the output stage had full short circuit protection. Two stages of voltage amplification were used, the so-called two-stage scheme. The LM101 was stable with a single external correction capacitance of just 30pF.

It was here that Vidlar made an error when he did not try to pack this capacitance on the crystal of the operational amplifier. A year later, as mentioned above, this gap was filled by competitors from Fairchild, and the A741 was released; roughly speaking, clone LM101 with internal frequency correction. This easy-to-use microchip has won the universal OU market.

A741

In the following years (1968 - 1969), Vidlar and Telbert developed and debugged new active devices in production: super-beta transistors , a multi-collector bipolar transistor and an epitaxial field-effect transistor

In 1969, Vidlar developed the first super-beta transistor operational amplifier, which was named the LM108 .

At the end of 1969, a new operational accelerator was released, the functional equivalent of the LM101 on the new element base - LM101A .

In 1970, the LM101 version with built-in correction capacity, the LM107 , was developed.

Telbert's six-hour process technology later allowed both pinch resistors, field-effect transistors, super-beta transistors, and side pnp transistors with a current gain of over 100 to be implemented on a single chip. The number of transistors serving current sources LM101A was reduced through the use of multicolumn pnp transistors. The input impedance of the operational accelerator, which did not use composite transistors at the input, for the first time exceeded the level of 1 MΩ.

From 1963 to 1971, Robert Vidlar wrote more than 50 articles on linear topics, where he described the “insides” of the OS, methods of their application. Vidlar patented integrated structures: side pnp, band-gap supporting element, super beta transistor, low voltage (1.2 V) amplifiers and others.

National Semiconductor released the Vllar LM100 , which was the first integral voltage regulator in history. The LM100 stabilized voltages from 2 to 30V with a cumulative error in the military temperature range (55 to 125C) not more than 1%. The reference voltage source the 6.3V Zener, the regulating element is a relatively low-power composite transistor, so in practice the LM100 was used not as a complete stabilizer, but as an external power transistor control circuit. The demand surpassed the most istichnye expectations. "

In 1970, the LM109 was produced - the world's first integrated three-output voltage regulator for 5V, which became the direct predecessor of the A7805 . Its creation was preceded by the requirement of customers to combine a control circuit and a power transistor on a single chip, while packing a full-fledged stabilizer into a case with three terminals: input, output, and common. Vidlar stated that such an arrangement of a power transistor and a control circuit on a single chip is not only permissible, but also greatly simplifies the overheating protection circuit. Such a stabilizer has already been implemented in silicon and was ready for serial production.

The LM109 microcircuit differed from the LM100 in limiting values of current and power, in its ease of use, the source of the reference voltage in an opamp was no longer served by a Zener diode, but by the Vglar bandgap .

The simplest implementation scheme for bandgap Vidlar

Bandgap Vidlar - transistor voltage reference, approximately equal to the width of the forbidden zone of silicon (about 1.2V). Vidlar was the first to design the first practical bandgap principle (which was formulated back in 1964 by David Hilbiber). LM109 was the first chip with integrated bandgap.

In 1971, the LM113 was developed, which was a two-pin precision diode in the Vidlar bandgap. Replacing the high-voltage (about 6V) Zener diode with a low-voltage (1.2V) bandgap made it possible to create cost-effective stabilizers for low output voltages (3.3V, 2.5B and below) and amplifiers with low-voltage power (from 1.1V).

At the beginning of the 70 Robert Vidlar disappeared. In 1971, the legend moved to Mexico, then he began working in his new company Linear Technology Corp (abbreviated LTC). It was rumored that in Mexico, the tax press was "softer" than in the United States.

Many call Robert Widlar - Steve Jobs 70 years. He was brilliant, but at the same time paranoid. His passion for a glass is often mentioned on the pages of his biography. But, surprisingly, he was unusually efficient, he could work on the microcircuit for days, months ... and only then he went into the booze. He was sick of work, not feeling tired - worked.

Although Robert came to electronics before the spread of computer simulation of electronic circuits, until the end of his life he refused to use them.

Owning the traditional skills of mathematical analysis, he could, for several hours, without interruption, be engaged in calculations, and then without a single mistake, put the results on paper. Vidlar wanted to control everything; the entire product development cycle, including sales, was to be under its control. Developing schemes, wrote to them all the technical documentation, up to a detailed guide to their use.

“Vidlar called this approach minimizing future phone calls. But despite this, colleagues not only called, but also wrote Vidlar many letters with questions. Vidlar’s precise and prompt answers generated in the professional environment the opinion that he himself wrote the answers to each addressee. In fact, Vidlar's letters consisted of model paragraphs, reprinted from his outline. Having received a letter with a question (and the questions inevitably recurred), Vidlar only pointed out to the secretary the paragraphs of the abstract that should have been reprinted, and then signed the ready answer. ”

After Bob retired from Fairchild, the problem of alcohol was even worse. He spent the night in bars, drunk to a semi-conscious state.

He was cocky, in one of the night showdowns, after drinking, he “invited” Mike Scott (the future president of Apple) to go out to talk, this conversation ended in a knockout of Widlar. Later, Vidlar began to drink continuously, his antics covered and even rescued him from arrest. Here is what Spork recalled about Widlar's drunkenness: "... He drank too much, and I had to endure it. I had no choice: this guy, for a while, was National Semiconductor. Once, at a seminar in Paris, we gathered about 1,200 engineers from We made a mistake in France and Belgium by opening access to the bar at lunchtime - in France it was so accepted.

And so he began to drink gin, neat, with large glasses, and I realized - to be in trouble. After lunch, he returned to the hall with a full glass of gin. I got to Peter Sprague, who was sitting next to Vidlar, and said to him: Peter, get rid of this gin before Vidlar falls under the table. Poor Peter sacrificed himself and drank everything to the bottom. At the beginning of his speech, Vidlar habitually reached for his glass, but it was empty. Vidlar shouted that he would not utter a word until a glass was poured over him. There was no choice, I had to pour him a full glass, and he continued. He could barely stand on his feet, but what is interesting is that even in such a state he fascinated the listener. And then I took him to the hotel by subway. He stood, reeling, at the very edge of the platform, and I stood at the back, ready to grab him. If he had fallen on the rails, the company would have died with him. "

The legendary sheep of Robert Vidlar

At the end of 1970, Vidlar decided to leave National Semiconductor.The company, in order to save, refused to mow lawns in front of the main building ... Bob decided to make a gift to the company). For $ 60, he bought a sheep from a familiar farmer and, being unhappy with the view of an overgrown meadow (where he parked his two-seater Mercedes), let the animal “trim” the lawn. Vidlar invited a San Jose News reporter for publicity to write an article with a comment from Bob about how "... a sheep has left many gardeners without work, but it can not only cut it, it can also fertilize!"

A sheep was stolen at night. There are many legends and myths around this story. Someone said that Vidlar himself took a sheep and drank it in one of the bars, according to another version, the sheep was not a sheep at all, but a goat, or, better still, a goat.

The last 20 years of his life, Vidlar worked under contracts with National Semiconductor and was engaged in some kind of uncertain development of production processes. From 1971 to the end of 1989, he issued only 8 patents for inventions. After the dismissal, he got a million dollars in his hands, went to Mexico and settled in Puerto Vallarta.

At thirty-three, Vidlar, finally got the freedom she dreamed of. He did not work on a permanent job. Vidlar continued to work alone on complex circuit design issues, occasionally lecturing in the USA.

In 1974, Spord managed to persuade Widlar to return to National Semiconductor. Vidlar became an independent company consultant, while living in Mexico. From 1974 to 1991, Widlar developed dozens of new projects for National Semiconductor.

In 1976, the LM10 was developed . This is a micropowerful operational amplifier and a reference voltage source, which is capable of operating at a supply voltage from 1.1 to 40 V, the first operational amplifier fully capable of operating from a single 1.4 V electroplating cell.

After the LM11 was developed , a precision bipolar OU which was designed for electrometric measurements.

In 1987, the first powerful (10 A, 80 W) LM12 operational amplifier was launched .

On February 27, 1991, the body of Widlar was found in the vicinity of Puerto Vallarta. There was a version that Bob died of a heart attack while jogging on the beach. But Bob Pease rejected this version, as usually Vidlar ran in the mountains, perhaps the attack caught him as he went down the slope, fell and died. The fact remains, the legendary personality was gone at the age of 53 years. As Vidlar himself assured, recently he settled down, even started a permanent relationship with a woman, stopped drinking alcohol. But predisposition to heart disease and lifestyle in young years, alas, did not go "without a trace."

He did not drink and did not sink. In no case. He was fine, he was in his right mind death came when he lived with dignity and soberness.

The unpredictability, genius of Robert Vidlar mixed with his love for alcohol, hermit lifestyle made him, even during his lifetime, a legend.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/368573/

All Articles