High Frequency Trading: Pros and Cons

The publication The Atlantic has published material in which he spoke about the role of high-frequency traders who are active on exchanges around the world. What are the advantages of their activities, and how it can harm the markets - read our adapted translation of this story.

What gives the market HFT

As the American financier Justin Fox rightly points out (Justin Fox) - throughout the history of stock trading, there have always been some intermediaries who received their commission. Nowadays, thanks to the growth of markets and the development of technology, this commission has become smaller, but it still exists. This money is received by intermediaries who guarantee that there will be a seller for each buyer and vice versa.

')

But today another type of intermediary has appeared. They do not work on exchanges or in banks. They work in hedge funds and are engaged in trading at breathtaking speeds. These high-frequency traders (HFT) use computer algorithms - the so-called. robots - for, for example, arbitrage transactions that allow you to earn on the difference in prices of related financial instruments at different exchange platforms that may occur during infinitesimally short periods of time.

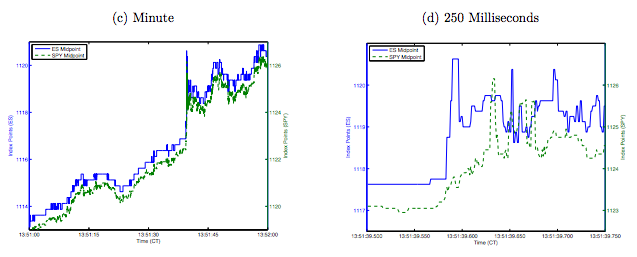

To understand how quickly everything actually happens, you can refer to the schedule from research by scientists Eric Budish (Eric Budish) and John Shim (John Shim) from the University of Chicago and Peter Cramton (Peter Cramton) from the University of Maryland. They used the 2011 data to show the difference in price between futures (blue line) and trading volumes (green line) - both values refer to the S & P 500 index. These two lines should perfectly correlate, and everything happens - in minute time intervals.

But if you look at the interval of 250 milliseconds, the correlation disappears - and this is slightly less than half the time it takes to blink. This phenomenon is market inefficiency, which is “corrected” by high-frequency traders.

In this regard, the development of robotic trading helps "ordinary" investors. Bid-ask spreads - that is, the difference between how much buyers want to buy, and sellers to sell - over the past 20 years has decreased significantly. This is partly a consequence of decimation (in the early 2000s, the New York Stock Exchange switched to the decimal system when trading - the price move began to equal 1 cent, and not 1/16 of a dollar). Another important factor is the proliferation of electronic trading, which, even in not so quick times, contributed to the growth of liquidity. And another reason - HFT-traders have added even more liquidity to the markets, reducing bid-ask spreads. The researchers found that when in 2012 the Canadian government introduced additional fees to limit high-frequency trading, bid-ask spreads on the country's exchanges increased by 9% .

Not so simple

All this, however, does not mean at all that high-frequency trading is an unequivocal benefit. As Noah Smith, a financial observer for Bloomberg, says, we do not have enough data to analyze all the pros and cons.

We only know that, on the one hand, reduced bid-ask spreads are a plus. But how much is this big advantage for the market? On the US stock exchanges now the bid-ask spreads are 3 basis points, 20 years ago this number was 90. This means that even if, like in Canada, HFT-traders reduced from 9%, their final impact is not so serious.

All this may have other consequences. In his book The Fast Boys (Flash Boys), Michael Lews describes some of them. Here are the three biggest factors that critics call “high-frequency trading costs”.

1. He does not create a market, but “takes” it.

The protagonist Lewis, a trader named Brad Katsuyama, had a problem. Every time he tried to buy shares for his client, he managed to buy at the right price only a small amount of securities. For example, on one exchange it was possible to buy at the right price, but on others the price managed to “slip” to a higher level by the time the transaction was executed. What is the matter here?

Katsuyama became a victim of frontranning . Therefore, part of his order was executed at the right price only on the stock exchange, which was physically closer to him - to which the signal on the optical fiber should have gone less - but not on other sites. HFT-robots saw his order on the first exchange, and then rushed to others to buy there the share he needed, and then resell more expensive. That's what happens all the time - Nicholas Hirschey from the London School of Business found that HFT funds are aggressively buying stocks right before someone places a large buy order.

This is what university professor Barnard Rajiv Networks (Rajiv Sethi) calls “unnecessary financial intermediation” - HFT traders “wedge in” between sellers and buyers who would already find each other after a couple of milliseconds.

2. Nobody wants to lose the robot

As Lewis writes, “When markets became less transparent, Katsuyama lost interest in working for them, adding liquidity.” This is what the Economist calls “ unfavorable selection ”, the idea is simple: the number of HFT traders is growing, because ordinary merchants do not want to fight against robots, which they probably lose, which means they need their own robots.

This also applies to HFT-funds. According to the former Reuters editor and the current senior editor of Fusion Felix Salmon (Felix Salmon), the share of HFT trading on American exchanges has decreased from 61% in 2009 to 51% in 2012. Why? Everything is simple - now the robots are fighting with each other, and these battles are not limited to just making deals.

As Johannes Breckenfelder from the Institute of Financial Researchers found out, HFT robots change their strategies when they compete with their own kind in this way. They are not engaged in "creating a market" and trying to buy or sell shares at a certain price - in this case they can lose the same way they do. They are trying to act smarter. As a result, there is less liquidity in the market, and volatility increases, at least within a specific trading day. (HFT-traders do not hold overnight shares, so volatility does not change over several trading sessions.)

3. Waste of money and talent

Very often, for particular people, high-frequency trading is profitable, but it is absolutely useless for society as a whole. Take Spread Networks, for example. In her book, Lewes describes in paints how her specialists dragged the fiber-optic line between Chicago and New York along the most direct route, in order to shorten the transaction time between two sites by three milliseconds.

To do this, they had to cut a gap in the Allegheny Mountains, and the whole operation cost $ 300 million. At the same time, it was necessary to avoid laying the cable on both sides of the road, as the CEO of Spread Networks believed that "it would cost a hundred nanoseconds."

Felix Salmon is right that such infrastructure costs carry some advantages. But in general, the question sounds like, does it make sense in such costs, if by and large, only HFT merchants can benefit from them? Considering that there are many tasks in the world that are worthy of spending money on their decision. Perhaps there is no point.

The problem is that tweeters have to spend this money. This is an arms race , and the one who comes in her second will not be awarded a silver medal. The fact is that the HFT strategy should not be faster than ordinary investors, but faster than other high-frequency robots. Every time someone manages to reduce the time of a transaction by a couple of microseconds, this means the need for huge expenses. Or defeat in a fight with those who are willing to go to these expenses.

But it is also an intellectual arms race. HFT is not only about how to send applications faster by wire (or microwaves ). It is also about the speed of data processing algorithms. And getting the best algorithm requires the work of real mathematical talents. Budish, Cremton and Shim point out that despite the reduction in the duration of arbitrage opportunities due to the actions of high-frequency traders from 97 milliseconds in 2005 to 7 milliseconds in 2011, the profitability of these operations has not changed. That is, HFT does not remove these market inefficiencies. Now they simply "disappear" faster than a person can blink.

Conclusion

HFT has real costs, and it is difficult to give this phenomenon an unequivocal assessment. Perhaps the reduced bid-ask spreads allow you to close your eyes to other cons, and maybe not. Bid-ask spreads will not return to the level of 1999, if today we just take and ban HFT.

It is necessary to understand that there are different players on the market - these are long-term investors, speculators, and algorithmic traders (we wrote about it in more detail here ). The actions of each of them are determined by different approaches and even philosophical attitudes. Therefore, it is impossible to compare HFT, for example, with long-only funds.

HFT traders can be called athletes who compete with the same tweeters, and sometimes with themselves.

Other HFT articles from ITinvest

- Investigation: As October 15, 2014, high-frequency traders crashed the US Treasury bond market and manipulated it

- Flash Crash 2010: Trillion Dollar Prime Suspect

- Algorithms and trading on the stock exchange: Hiding large transactions and predicting the price of shares

- Online algorithms in high-frequency trading: problems of competition

- What's New: 3 technological trends in algorithmic trading

- Experiment: Is it possible to create an effective trading strategy using machine learning and historical data

- Creating trading robots: 11 development tools

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/367143/

All Articles