The world's first counting device - Schickard machine

In 1957, the Director of the Keplerovsky Scientific Center, Franz Hammer, made a presentation at a seminar on the history of mathematics, held in Germany. He made a sensational news that the project of the first counting machine appeared for several decades before the famous "wheels" of Pascal. The first counting device was invented in the middle of 1623 and was called the Schickard machine.

The discovery of this fact Hammer made almost by accident. When he worked in the Stuttgart library, he came across a mysterious photocopy of a sketch of a counting device. And since I had never seen anything like this before, I became very interested in an unknown sketch. After conducting a series of studies, Hammer found that the sketch found was the missing appendix to the letter of William Schickard, a professor at the University of Tübingen, addressed to his colleague mathematician Johann Kepler. In his letter, Schickard described the counting machine in detail and referred to the drawing.

')

copy of the sketch

A bit of history

Wilhelm Schickard was born on April 22, 1592 in the city of Herrenberg (Germany). He was extremely talented and already at the age of 17 he received a master’s degree from the University of Tübingen, and two years later became a Bachelor of Science. He gained worldwide fame for his achievements in the sciences: astronomy, mathematics and oriental studies (Professor of the Oriental Languages Department at the University of Tübingen). And also, Shikkard created the first computing machine.

Wilhelm Schickard (1592-1635)

From 1617, Schickard began teaching Oriental languages at the University of Tübingen. There he met Kepler, who appreciated the extraordinary abilities of the young scientist and recommended him to study mathematics. Schickard obeyed his advice and achieved considerable success in the new field. In 1631 he became a professor of mathematics and astronomy at the University of Tübingen.

Shikkard was a pioneer in other areas. Like for example - in astronomy. The scientist constantly developed, corresponded with many German, French, Italian and Dutch scientists on matters relating to astronomy. He created the first mechanical planetarium, which clearly demonstrated the position of the Sun, Earth and Moon according to the Copernican system. In addition, I observed meteors from different points to determine their trajectories.

The breadth of interests of Shikkard really deserves respect. He was an experienced mechanic, cartographer, wood and metal engraver, conducted astronomical observations, wrote treatises on Semitic languages, astronomy, mathematics, optics and meteorology. The scientist has achieved outstanding scientific success and was truly a brilliant inventor. But it was powerless before the cholera epidemic. This merciless disease of the XVII century in 1635 took the life of Shikkard and his family. The works of the scientist at the time were forgotten because of the Thirty Years War.

Shikkard machine - the beginning of the XVII century

In one of the letters to Kepler (dated September 20, 1623) it was reported that Schickard mechanically carried out everything that Kepler did algebraically, namely, he constructed a machine that automatically performed addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Shikkard wrote that Kepler was pleasantly surprised if he saw how the device itself accumulates and transfers to the left a dozen or a hundred numbers and how it takes away what it held in memory during subtraction.

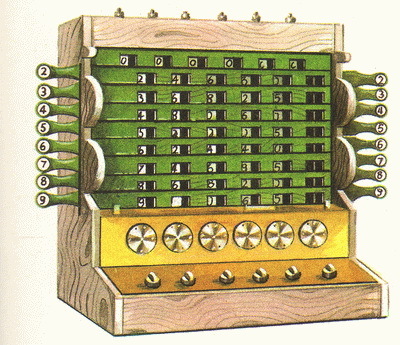

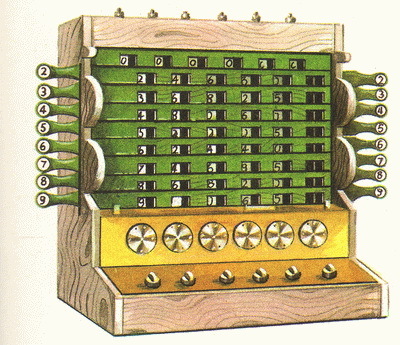

The invention, which became the first counting machine, was created in 1623. Shikkard invented and developed a model of a six-digit mechanical computing device that performs simple mathematical functions, such as - add and subtract numbers. Not for nothing, he was called "the clock for the account." The Schickard machine contained summing and multiplying devices, as well as a mechanism for recording intermediate results.

From a letter to Kepler:

Johann Kepler (1571-1630)

A more detailed description helps to get an idea of the invention. The first block in the form of a six-digit summing machine was a combination of gears. On each axis there was a gear with ten teeth and an auxiliary single-tooth wheel - a finger. The finger served to transfer the unit to the next digit, that is, to turn the gear to a tenth of a full turn, after the gear of the previous discharge makes such a turn. When subtracting the gear needed to rotate in the opposite direction. It was possible to control the course of calculations with the help of special windows where numbers appeared. A device was used for multiplication, the main part of which consisted of six axes with multiplication tables “screwed” on them. The subtraction was performed by rotating the setting wheels in the opposite direction, since the transfer mechanism of dozens was reversible.

In fact, the work of the machine Schickard was pretty simple. For example, to find out what is the product of 296 x 73, you need to set the cylinder in a position that allows you to display the first factor in the top row of windows: 000296. The product 296 x 3 is obtained if you open the windows of the third row and sum up the numbers you see, as in lattice mode . Then, in exactly the same way, the windows of the seventh row open, giving the product 296 x 7 to which the fame is attributed to 0. And it remains only to add the numbers found on the summing device. All result is ready.

The unresolved question remains - was the actual model of the machine assembled during the life of the scientist? There is very little data on this. In the letters of Schickard, all the same to Kepler it is a question of a “practically finished” copy of the device, which burned down during a fire. He was in development with the mechanic Wilhelm Pfister. Whether the second model of the car was assembled is not known for certain. Most likely, no one except Shikkard and Pfister saw the finished and acting device. In any case, evidence of performance has not been preserved.

But what is for sure - for a long time, the Schickard machine remained known only to a narrow circle of trustees. And this invention could not influence the subsequent development of account mechanization. Who knows, maybe with the help of this project the progress of computing devices could be accelerated. But anyway, the name of the German scientist Wilhelm Schickard is on a par with the great minds, the inventors of calculating devices of the XVII — XIX centuries. Such as Blaise Pascal, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Charles Babbage, Paphnuti Lvovich Chebyshev, Herman Hollerith and others.

modern prototype of the Shickard machine

Based on materials found by Hammer, staff at Tubingen University in the early 1960s created a working model of Schickard machine. The operations of addition and subtraction were carried out mechanically in it, and multiplication and division - with elements of mechanization. The prototype of the invention is owned by the university.

The evolution in computing technology is a rather uneven process that occurs abruptly from periods of decline to periods of decline. The achieved results are used in practice and each new step brings the process of computational evolution to a new, higher level.

The discovery of this fact Hammer made almost by accident. When he worked in the Stuttgart library, he came across a mysterious photocopy of a sketch of a counting device. And since I had never seen anything like this before, I became very interested in an unknown sketch. After conducting a series of studies, Hammer found that the sketch found was the missing appendix to the letter of William Schickard, a professor at the University of Tübingen, addressed to his colleague mathematician Johann Kepler. In his letter, Schickard described the counting machine in detail and referred to the drawing.

')

copy of the sketch

A bit of history

Wilhelm Schickard was born on April 22, 1592 in the city of Herrenberg (Germany). He was extremely talented and already at the age of 17 he received a master’s degree from the University of Tübingen, and two years later became a Bachelor of Science. He gained worldwide fame for his achievements in the sciences: astronomy, mathematics and oriental studies (Professor of the Oriental Languages Department at the University of Tübingen). And also, Shikkard created the first computing machine.

Wilhelm Schickard (1592-1635)

From 1617, Schickard began teaching Oriental languages at the University of Tübingen. There he met Kepler, who appreciated the extraordinary abilities of the young scientist and recommended him to study mathematics. Schickard obeyed his advice and achieved considerable success in the new field. In 1631 he became a professor of mathematics and astronomy at the University of Tübingen.

Shikkard was a pioneer in other areas. Like for example - in astronomy. The scientist constantly developed, corresponded with many German, French, Italian and Dutch scientists on matters relating to astronomy. He created the first mechanical planetarium, which clearly demonstrated the position of the Sun, Earth and Moon according to the Copernican system. In addition, I observed meteors from different points to determine their trajectories.

The breadth of interests of Shikkard really deserves respect. He was an experienced mechanic, cartographer, wood and metal engraver, conducted astronomical observations, wrote treatises on Semitic languages, astronomy, mathematics, optics and meteorology. The scientist has achieved outstanding scientific success and was truly a brilliant inventor. But it was powerless before the cholera epidemic. This merciless disease of the XVII century in 1635 took the life of Shikkard and his family. The works of the scientist at the time were forgotten because of the Thirty Years War.

Shikkard machine - the beginning of the XVII century

In one of the letters to Kepler (dated September 20, 1623) it was reported that Schickard mechanically carried out everything that Kepler did algebraically, namely, he constructed a machine that automatically performed addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Shikkard wrote that Kepler was pleasantly surprised if he saw how the device itself accumulates and transfers to the left a dozen or a hundred numbers and how it takes away what it held in memory during subtraction.

The invention, which became the first counting machine, was created in 1623. Shikkard invented and developed a model of a six-digit mechanical computing device that performs simple mathematical functions, such as - add and subtract numbers. Not for nothing, he was called "the clock for the account." The Schickard machine contained summing and multiplying devices, as well as a mechanism for recording intermediate results.

From a letter to Kepler:

... aaa - these are the upper ends of the vertical cylinders, on their side surfaces multiplication tables are plotted; If necessary, the figures of these tables can be observed in the bbb windows of sliding slats. From the inside of the car, wheels with ten teeth are attached to ddd disks, each of which is in such engagement with its own kind that if any right wheel turns ten times, then the wheel to its left will make one turn, or if the first of the wheels mentioned makes 100 turns , the third from the left wheel will turn once. In order for the gears to rotate in the same direction, it is necessary to have intermediate wheels ...

Johann Kepler (1571-1630)

A more detailed description helps to get an idea of the invention. The first block in the form of a six-digit summing machine was a combination of gears. On each axis there was a gear with ten teeth and an auxiliary single-tooth wheel - a finger. The finger served to transfer the unit to the next digit, that is, to turn the gear to a tenth of a full turn, after the gear of the previous discharge makes such a turn. When subtracting the gear needed to rotate in the opposite direction. It was possible to control the course of calculations with the help of special windows where numbers appeared. A device was used for multiplication, the main part of which consisted of six axes with multiplication tables “screwed” on them. The subtraction was performed by rotating the setting wheels in the opposite direction, since the transfer mechanism of dozens was reversible.

In fact, the work of the machine Schickard was pretty simple. For example, to find out what is the product of 296 x 73, you need to set the cylinder in a position that allows you to display the first factor in the top row of windows: 000296. The product 296 x 3 is obtained if you open the windows of the third row and sum up the numbers you see, as in lattice mode . Then, in exactly the same way, the windows of the seventh row open, giving the product 296 x 7 to which the fame is attributed to 0. And it remains only to add the numbers found on the summing device. All result is ready.

The unresolved question remains - was the actual model of the machine assembled during the life of the scientist? There is very little data on this. In the letters of Schickard, all the same to Kepler it is a question of a “practically finished” copy of the device, which burned down during a fire. He was in development with the mechanic Wilhelm Pfister. Whether the second model of the car was assembled is not known for certain. Most likely, no one except Shikkard and Pfister saw the finished and acting device. In any case, evidence of performance has not been preserved.

But what is for sure - for a long time, the Schickard machine remained known only to a narrow circle of trustees. And this invention could not influence the subsequent development of account mechanization. Who knows, maybe with the help of this project the progress of computing devices could be accelerated. But anyway, the name of the German scientist Wilhelm Schickard is on a par with the great minds, the inventors of calculating devices of the XVII — XIX centuries. Such as Blaise Pascal, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Charles Babbage, Paphnuti Lvovich Chebyshev, Herman Hollerith and others.

modern prototype of the Shickard machine

Based on materials found by Hammer, staff at Tubingen University in the early 1960s created a working model of Schickard machine. The operations of addition and subtraction were carried out mechanically in it, and multiplication and division - with elements of mechanization. The prototype of the invention is owned by the university.

The evolution in computing technology is a rather uneven process that occurs abruptly from periods of decline to periods of decline. The achieved results are used in practice and each new step brings the process of computational evolution to a new, higher level.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/367083/

All Articles