The History of Thomas Edison Cylindrical Phonograph

The phonograph was invented as a result of the work of Thomas Edison on two other inventions: the telephone and the telegraph. In 1877, Edison worked on a device that could record messages in the form of grooves on a paper tape, which could then be repeatedly sent via the telegraph. The study led Edison to the idea that you could also record a telephone conversation in this way. He experimented with a membrane fitted with a small press held above a fast-moving paraffin-coated paper. Vibrations created by voice, left marks on paper.

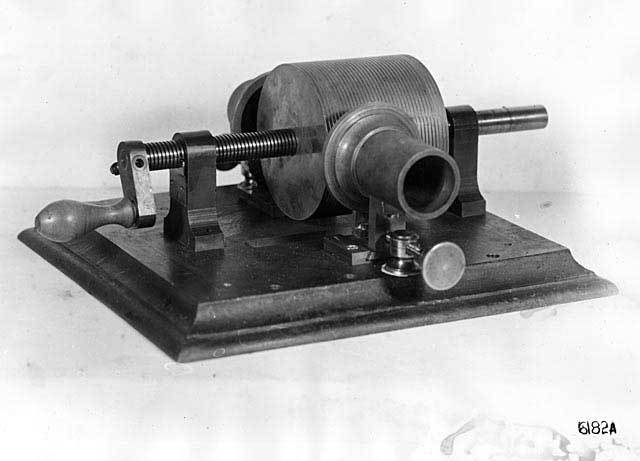

The phonograph was invented as a result of the work of Thomas Edison on two other inventions: the telephone and the telegraph. In 1877, Edison worked on a device that could record messages in the form of grooves on a paper tape, which could then be repeatedly sent via the telegraph. The study led Edison to the idea that you could also record a telephone conversation in this way. He experimented with a membrane fitted with a small press held above a fast-moving paraffin-coated paper. Vibrations created by voice, left marks on paper.Later, Edison replaced the paper with a metal cylinder wrapped in tin foil. The device had two elements in the form of a membrane connected to the needle — one for recording and the other for reproduction. When someone spoke into a horn, the sound vibrations impacted the recording needle, and it left grooves of different depths on the cylinder. Edison gave a sketch of the scheme of the device to his mechanic John Kruezi (John Kreusi), and he allegedly built the car in 30 days.

Edison immediately tested the car, saying the nursery rhyme "Mary had a lamb" in the mouthpiece. To his surprise, the device reproduced what he said. Although it was claimed that this event took place on August 12, 1877, some historians believe that it may have happened several months later, because Edison did not file a patent application until December 24, 1877. Also, in Charles Batchelor’s diary, one of Edison's assistants, contains a record saying that the phonograph began to be constructed on December 4, and was completed in two days. The patent for the phonograph (# 200,521) was issued on February 19, 1878. The invention was very original. The only mention of such an invention was found in the work of the French scientist Charles Cros, which he wrote on April 18, 1877. Cro and Edison were different in their ideas, but Cro did not create a working model of the phonograph, and his work remained a theory.

')

Original Edison phonograph (tin foil used in the design). Photo courtesy of the US Department of the Interior, National Park Service and Edison National Historic Site

Edison took his new invention to the Scientific American office in New York and demonstrated his work. In the December 22, 1877 issue, there was an article: “Mr. Thomas Edison recently came to our office, put a small device on our table, turned the handle, and the device took an interest in our health, asked if we liked the phonograph, spoke about its advantages, and kindly wished us good night. " The device aroused great interest, and it was told about it in several newspapers in New York, and later in other American newspapers and magazines.

On January 24, 1878, Edison founded The Edison Speaking Phonograph, a company that made money by demonstrating a phonograph to people. Edison earned $ 10,000 by selling manufacturing rights and also received 20% of sales. The novelty had incredible success, but only experts could work with the device, and the foil was enough for only a few reproductions.

In an interview for North American in June 1878, Edison spoke about the possible applications of the phonograph:

- Dictation and recording of letters without resorting to the help of stenographers.

- Talking books that will be read for blind people.

- Teaching oratory.

- Playing music.

- “Family Records” - records of aphorisms and memories of family members in their own voices, the last words of the dying and much more.

- Music boxes and toys.

- Hours that will notify about lunch time, the end of the working day and much more.

- Preservation of languages, by accurately reproducing the manner of speech.

- Educational goals; for example, recording material given by the teacher so that the student can always refer to them. Record spelling lessons or any other for easy memorization.

- An auxiliary device connected to the telephone to transmit short, multiple information in order to avoid monotonous short-term calls.

Over time, the device came into use, and Edison did not make any improvements in the design of the phonograph, instead he focused on creating an incandescent lamp.

Since Edison left the work on the phonograph, others began to improve it. In 1880, Alexander Graham Bell received a Volt prize of $ 10,000 from the French government for inventing the telephone. Bell used the money to create a laboratory for further research on electrical and acoustic phenomena. He worked with his cousin Chichester A.Bell, a chemical engineer and Charles Sumner Tainter, a scientist and mechanic. They perfected Edison's invention somewhat by using wax instead of tin foil and replacing the fixed needle of the recorder with a moving pen that cut the wax instead of pushing the grooves on the foil.

The patent was handed to C. Bell and Tainter on May 4, 1886. The device was presented to the public as a graphophone. Bell and Tainter sent representatives to Edison to discuss possible cooperation to improve the device, but Edison refused and decided to do it on his own. By this time he had already completed the creation of the incandescent lamp and could now resume his work on the phonograph. Edison called the improved invention the New Phonograph, in which he also used Bell and Tainter wax cylinders.

The Edison Phonography Company The Edison Phonograph Company was founded on October 8, 1887 to sell the Edison car. He introduced the Improved Phonograph in May 1888, followed by the Perfect Phonograph. The first wax cylinders that Edison used were white and made from ceresin, beeswax and stearin wax.

Edison's Home Phonograph

Entrepreneur Jesse H. Lippincott (Jesse H.Lippincott) took control of the phonographic companies by purchasing the Edison Phonography Company and becoming the only licensee of the American Graphophone Company. Agreeing with other phonographic companies, he founded the North American Phonograph Company on July 4, 1888. Lippinkot saw the potential of phonographs only from a financial point of view, and leased them to various partner companies as text dictation machines. Unfortunately, the business was not very profitable, because it could not compete with stenographers.

Meanwhile, in 1890, Edison's factory made talking dolls for the company of phonographic toys (Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Co). Tiny wax cylinders were used in these dolls. Today it is very difficult to find such dolls, since Edison ceased cooperation with the company in 1891. The phonographic plant also produced musical cylinders for jukeboxes, which began to be used in some subsidiaries. Prototypes of jukeboxes have shown that entertainment is the future of phonographs.

In the fall of 1890, Lippincott fell ill and handed over control of the North American phonographic company to Edison, who was his main creditor. Edison made several changes to the company's policy - one of the changes was the decision to start selling phonographs, and not to rent them out.

Edison increased production of cylinders for entertainment purposes. In 1892, such cylinders were made from wax, today known among collectors as “brown wax”. Although the word “brown” was in the title, the color of the cylinders could vary from off-white to light brown or dark brown. The name, the performer and the manufacturer were indicated on the edge of the cylinder.

[Left: A poster with an Edison Phonograph of the new standard in Harper magazine, September 1898]

[Left: A poster with an Edison Phonograph of the new standard in Harper magazine, September 1898]In 1894, Edison announced the bankruptcy of the North American phonographic company, which allowed him to redeem the rights to his invention. It took two years to settle the bankruptcy case, so that Edison could continue to promote his invention. Edison's phonograph with a spring motor appeared in 1895, although at that time Edison was not allowed to sell phonographs due to the bankruptcy agreement. In January 1896, he founded the National Phonograph Company (National Phonograph Company), which produced phonographs for home and entertainment purposes. For three years, the company's branches spread throughout Europe. In 1896, under the auspices of the company, he announced a spring motor phonograph, followed by Edison's home phonograph, and began producing cylinders. A year later, the standard Edison phonograph, created in the press only in 1898, was created. It was the first phonograph created to promote a new brand. Compared to earlier versions of phonographs, their prices have declined. For the standard model they asked for $ 20, instead of $ 150, as in 1891, and for the model, known as GEM (gem), presented in 1899, $ 7.50.

Cylinders of a standard phonograph were 4.25 inches in length and 2.1875 inches in diameter, rotated at playback speed of 120 revolutions per minute during playback, and cost 50 cents each. Among the records on the cylinders one could find: marches, sentimental ballads, Negro songs, hymns, comic monologues and reconstructions of the events that occurred.

Early cylinder models had two major flaws. The first - a short cylinder length limited the recording time to 2 minutes, which narrowed the area of its application. The second drawback was that there was no way to create a large number of copies of the cylinders. To record several cylinders, the artists were forced to repeat their performances many times. This method of recording not only took a long time, but was also very costly.

Edison's concert phonograph, which has a louder sound and enlarged cylinders 4.25 inches long and 5 inches in diameter, was introduced in 1899 at a price of 125 dollars. The cost of the cylinders for it was set at $ 4. Sales of the concert phonograph were low, and as a result the price was lowered. Production was halted in 1912.

[Left: catalog of records for Edison cylinders, September 1911]

[Left: catalog of records for Edison cylinders, September 1911]Mass production of copies of wax cylinders launched in 1901. The grooves on the cylinders were melted, rather than cut out with a feather, and more solid waxes were used. The process was compared with the melting of gold, due to the gold vapor rising from the gold-plated electrodes used in the process. According to the reference sample, molds were made that were already used for the manufacture of cylinders. In one form, it was possible to create from 120 to 150 cylinders per day. The new wax used in the manufacture of cylinders was black in color and at first they were called “new high-speed records melted from solid wax,” but later they changed the name to “Cast from gold”. In the middle of 1904, mastering mass production made it possible to reduce the price of cylinders to 25 cents per piece. The beveled ends were made to accommodate titles.

A new phonograph for business was introduced in 1905. It looked like a regular phonograph, but it has undergone changes in the device of the loudspeaker and the reading needle. Early device models were difficult to use, and their fragility often led to breakdowns. Although the device was improved a few years later, it still cost more than the popular low-cost dictaphones from Columbia. Later, controls and electric motors were added to the Edison phonograph design, which improved the device's performance. (Some of Edison's phonographs, produced before 1895, also had electric motors, but they were replaced by spring motors).

After modifications, the phonograph for Edison’s business turned into a system for dictating text. The system used three devices: a dictating machine, a typing machine and a cylinder replacement unit. This system can be seen in the commercial “Friend of the Stenographer”, filmed by Edison in 1910. The improved Edifon device was introduced in 1916, and its sales after World War I grew steadily, until the 20s of the 20th century.

[Left: catalog of cast-cylinder records, March 1903]

[Left: catalog of cast-cylinder records, March 1903]In terms of playback time, 2-minute wax cylinders could not compete with competitors' disks, which made it possible to reproduce recordings of up to 4 minutes in duration. As a response to the disks in November 1908, the cylinder of the brand Amberol Record was presented, whose playback time increased to 4 minutes due to thinner grooves. Over time, the 2-minute cylinders became known as Edison's two-minute recordings, which later became known as standard Edison recordings. In 1909, the party of Grand Opera Amberols cylinders (as the heir to the two-minute Grand Opera cylinders, introduced in 1906) was introduced to the market to attract influential customers, but this attempt was unsuccessful. In 1909, the Amberola I phonograph was presented to the public. It was assumed that this luxury model with high quality of reproduction would compete with such models as Victrola and Grafonola. In 1910, the company was reorganized into the Thomas Edison Corporation (Thomas A. Edison, Inc.). Frank L. Dyer was its first president, after him Edison became president and remained in office from December 1912 until August 1926. After Edison, his son Charles became president, and Edison himself remained chairman of the board of directors.

Columbia - one of the main competitors of Edison, left the market for the sale of cylinders in 1912. (Columbia refused to produce its own cylinders in 1909, and until 1912 they sold cylinders purchased from Indestructible Phonographic Record). The United States Phonograph company ceased production of its cylinders under the brand USEverlasting in 1913, leaving the market to Edison. The disc has steadily gained popularity among customers, especially thanks to the artists who recorded their albums at the studio Victor. Edison did not abandon the cylinders and presented instead of Blue Amberol Record a cylinder that did not wear out over time and provided the best sound that could be achieved at that time. The thinner sound of the cylinder is partially due to its constant rotational speed at all points, in contrast to the disks, which began to rattle when the rotational speed is slowing.

Edison argued that a vertical groove of a groove produces a better sound than a side cut from Victor and other disc manufacturers. At that time, the cylinders found their regular audience, but could not compete with the discs, and even the best sound of the Blue Amberol cylinders could not increase the demand for them. Edison surrendered to the currents of time in 1913, when he announced Edison's disc phonograph. Edison's company did not forget the loyal customers of the cylinders and produced Blue Amberol cylinders until the company ceased to exist in 1929, although most of them were copies of Edison's diamond discs.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/364317/

All Articles