Hansen collaboration: either good or no

We received a selection from Milfgard for another novelty in the communal library of the team, for which we give the author a special thanks. Collaboration, networking and other overvalued communication with colleagues is a trend topic and, accordingly, arousing a spirit of controversy. Business analyst Morten Hansen takes a moderate and sober position in relation to this, which in a nutshell can be expressed in two theses:

- Collaboration as a company policy is beneficial if it is introduced meaningfully and according to a certain scheme, otherwise it is an inefficient waste of a resource;

- Collaboration should not become an end in itself - it is not always necessary, in many cases it is more expedient to abandon it

The book is conventionally divided into two parts. In the first, the researcher discusses why inefficient collaboration is so common, citing examples from its business analyst practice, reveals the concept of “rational collaboration” and tells how to evaluate the company's capabilities and prospects in this regard. The second is devoted to specific methods of restructuring the workflow for those who have decided that they need it.

')

Under the cut - our squeeze from the first part: the difference between a rational and inefficient collaboration, cooperation and independence, the barriers of collaboration and the factors that determine whether it is needed at all.

Collaboration Pitfalls

Let's go from the opposite: we first define what does not apply to rational cooperation. In its most general form, an ineffective collaboration is an interaction that is characterized by a large number of differences and a weak focus on results. Based on a number of cases from his practice, the author comes to the conclusion that it arises as a result of four types of errors made when planning collaboration strategies.

Collaborating in a hostile culture

It would be a mistake to consider that a collaboration is reduced to a set of practices that can be implemented in any environment. If the atmosphere in the company goes against the way of thinking necessary for it, the interaction will be conducted formally and will not bring results. Collaboration is impossible in organizations where competition and independence are encouraged - such an environment poisons any attempt at cooperation.

Excessive Collaboration

As John Leggate said, people always have a good reason to see each other. When leaders promote collaboration in their companies, they often get more than they expect - employees cross the border and begin to communicate for the sake of communication, without understanding the main goal. This leads to unnecessarily complicating the structure of the organization and wasting time on endless meetings.

Overpricing potential value

Some leaders place too much hope on the collaboration. It is very easy to get carried away with the idea that synergy between business units will bring huge benefits to the company simply by default. In fact, each individual case requires analysis and balance. When expectations are inflated, the result is often insufficient to recoup all costs.

Cost underestimation

Even being well aware of the benefits of cooperation, managers sometimes are not fully aware of what expenses (working time, technical means, personnel training) will require debugging work inside the organization and resolving conflicts. For example, if workers nestled a deep mutual distrust of each other, it is useless to wait for quick results - conflicts will “eat up” most of the resource.

Wrong definition of the problem

It is not enough just to state the fact that people do not interact enough with each other, it is also necessary to identify the causes. There are two completely different types of problems. The first is related to the lack of opportunities for workers to seek help, the second - with their internal resistance to working together. Leaders need to understand which collaboration barriers are relevant to their company. If any problem is not taken into account, she can sabotage all attempts to rectify the situation.

Making the wrong decisions

This is a direct consequence of the previous paragraph. Managers often fall into such a trap, confident that some kind of universal solution — an IT system, a motivation system, a common goal — will facilitate interaction under any circumstances. But different barriers of collaboration require different approaches.

Practice shows that even competent managers fall into these traps - they are hardly noticeable and it can be difficult to recognize them “in the field”. In order to clearly see the differences between high-quality and low-quality cooperation, it is necessary to understand what lies at the heart of a rational collaboration.

Example: as an illustration of how the traps knock leaders off course, the author describes Sony’s attempt to force Apple out of the new generation of music players in the market. The management did not take into account that up to this point in the company culture flourished, based on fierce competition and separate work of teams. The new project was large-scale and required the joint work of five autonomous units, some of which were located in the United States, the other part in Japan. Communication was so difficult that the most fundamental decisions were often taken by one of the groups unilaterally. The feedback on the interface, the wishes to the playback formats were ignored - in the end, the release of the Connect player turned into a great failure. Moreover, even the feverish “work on the mistakes” did not save the situation: the conflict between the groups became aggravated and productivity became even lower.

Rational Collaboration

The idea of a rational collaboration can be formulated in one phrase: this is a leadership practice that helps determine when it is beneficial to cooperate and when not, and training in subordinates desire and the ability to interact when necessary.

To implement a rational collaboration, leaders must complete three steps.

Step one: evaluate the possibilities of collaboration. Simply put, to answer the question: will it have a positive effect? Cooperation is not a value in itself, but a means of achieving the goal; the goal is high performance. To be rational in relation to interaction is to understand when it is not needed.

Step two: identify the barriers of the collaboration. What prevents people from interacting effectively under current conditions? Details of the types of barriers will be described later.

Step three: develop solutions for breaking down barriers. Different barriers require different leverage. The ultimate goal is not to make people interact more, but to ensure that the right people interact in the framework of the right projects.

Collaboration vs. decentralization

One of the reasons why many leaders are skeptical about the idea of collaboration as a management principle is the belief that it will inevitably lead to less independent work of the units.

Modern management seeks the following model of work: an organization is a decentralized system with clear areas of responsibility, high accountability and awards for those who have achieved good results in their field. This is an excellent system, it brings results - but only up to a certain point. The problem is that over time, independence may turn into disunity: managers are increasingly holding onto the interests of their area, employees only care about achieving their own goals and have little interest in helping others. In the end, decentralization risks turning the company into a weakly managed cluster of departments, as happened at Sony.

The solution, however, is not to eliminate the decentralized system and move to its opposite - maximum centralization, where all decisions are made and all information is processed by a few elected at the head of the company. Rational collaboration assumes that the organization functions as decentralized, but the work of the teams is coordinated.

Rational collaboration removes the need to choose between decentralization and cooperation. All departments within the organization work independently - this allows people to freely manage their work array, feel responsible, receive a response and reward for the results achieved. But this model is complemented by a collaborative layer - the ability to independently recognize when it is necessary to join forces with other groups.

Before introducing the proposed methodology into an organization, you need to understand where it is located along the 'autonomy-cooperation' axes. If the company adheres to a decentralized management model, you can proceed to the actions described in the next chapter. If the collaboration is a priority, but it is not well established, you should first prepare the ground by returning the ability and habit of independent work to employees.

When to cooperate, and when not

Transfer

Are you lonely? Tired of working independently? Do not like to make decisions? BUILD MEETING! You will be able to: see people, show charts, feel like an important person, poke a pointer, eat donuts, impress colleagues - all at the expense of the company!

Meeting: a practical alternative to work.

Meeting: a practical alternative to work.

To determine whether to start implementing a rational collaboration, you need to perform the following sequence of actions:

The first task: to determine the arguments in favor of the collaboration.

The second task: to assess the strengths of the company.

The third task is to understand when to say “no” to a collaboration project.

On the basis of these steps, the general rules are then formulated. when it is worth implementing a collaboration.

Arguments for collaboration

There are three areas of potential business growth:

1. Innovation

The most successful innovations occur when people from different areas get together, generate new ideas in the process of interaction and develop products together. The economic logic is to combine resources - products, knowledge, technology, brands, ideas - in order to create something new from the existing one. This practice leads to more innovation at lower cost.

Example: the company P & G throughout its history has used developments in current areas to develop new niches. Initially, the company was engaged in the production of candles and soaps; then their knowledge of using fats and oils allowed them to add peanut butter and chips to their range; long-term work with vegetable raw materials brought ideas on how to use fibers for the production of absorbent materials - and so on.

2. Growing sales

Another advantage of the collaboration is cross-selling, in which cross-divisions are often involved: one begins to offer its products to customers of another. The economic logic is that selling a greater quantity of goods to existing consumers is cheaper than seeking new consumers.

Example: many banks have introduced the practice of gradually expanding the range of services in different directions for the client. Consultants offer options, report on profitable promotions, transfer contacts to other departments, which subsequently communicate with the consumer. The number of services per client for companies that have mastered this technique well reaches 5-6.

3. Optimization of activities in general

The third argument in favor of cooperation is based on increasing the effectiveness of employee actions. Here the economic logic is to reuse the available resources. Methods that have proven their suitability for one department can be used in others.

Example: to solve the problem of urban poverty in the West African region, the experience of similar initiatives in Asia and Latin America was widely used - as a result, the development of a strategy to improve sanitation, design, and housing needed less effort and cost.

So, a collaboration affects sales, costs, and asset efficiency — the cumulative effect of all three parameters on capital profitability can be significant.

Strengths of the company

However, a natural question arises here: how applicable is it for your company, what value does it make sense to pursue? It depends on the specifics of the market, activities and other individual circumstances.

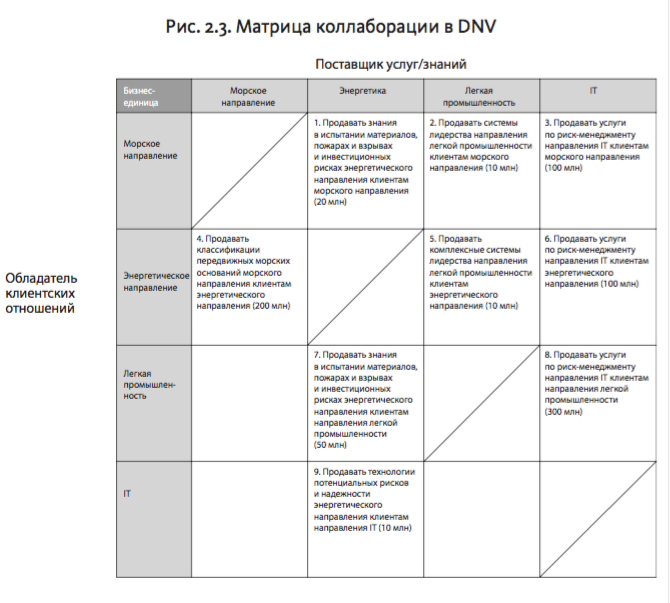

To create a differentiated approach to assessing prospects, the author advises using the collaboration matrix. Its meaning is to make all the admissible business pairs (a pair form any two divisions - from small teams to entire areas) and analyze their potential. By applying this systematic assessment method — pair by pair — the leaders can conduct a full analysis of the possibilities and calculate from which to really benefit.

As you remember, both overestimation and underestimation are the root causes of irrational collaboration. When looking at options, one should avoid generalizations and prejudices - not every couple can work together, but the opportunity itself should not be dismissed immediately.

When to say no to a collaboration?

Now that the goal is defined and outlined a range of possible ways to achieve it, it remains to answer the question whether it is worth it. This can be done on the basis of mathematical calculations.

The collaboration project should be launched only if the net value of the interaction is higher than the difference between the profit and the sum of the costs. The researcher calls this net value a collaboration premium — it can be expressed by simple equality:

Collaboration award = project profit - opportunity costs - collaboration costs.

Opportunity costs are the net cash flow that organizations miss by building interaction instead of doing something else.

Collaboration costs - cash costs arising from the above (extra travel, time spent on dialogue, the cost of resolving conflicts).

However, in order to correctly estimate the volume of these costs, it is necessary to have a clear idea of how things are in the company at the current moment. The number of additional investments that will be needed before the company moves to a new work model is determined by how many barriers it has.

Four Collaboration Barriers

Collaboration rarely occurs in a natural way, because leaders often inadvertently create barriers that prevent people from interacting.

Four barriers usually interfere with the interaction.

1. Barrier "not invented here"

This barrier arises as a result of problems with motivation - often people simply do not want to go beyond their divisions, receive new information and interact. Several factors contribute to this:

- Isolated culture: team cohesion has its disadvantages - its members go into themselves and are isolated from the outside world. As a result, the flow of ideas is limited, and new points of view do not receive development in a society of like-minded people. Solutions to emerging problems are sought within the team and performance decreases.

- The difference in statuses: people scornfully relate to the advice of those who "stand below" them in some respect. In turn, low-status workers are also uncomfortable to cooperate with their superiors - this deprives them of self-confidence. The status gap operates in two directions, making it difficult for employees to interact effectively.

- Self-sufficiency: it is the deep-rooted belief that people must solve their problems themselves. Seeking help for many means showing your incompetence and helplessness.

- Fear of showing flaws: asking for help, we put ourselves in a vulnerable position, we invite others to evaluate our work. Sometimes people are afraid to show their weak points to others and prefer to turn to those whom they know well and whom they trust, even if this is not the optimal solution.

2. Barrier hoarding

The previous paragraph dealt with the reluctance to ask for help, but there is an inverse problem. Some people deliberately avoid sharing with others - refuse to provide help, information, time and energy. Of course, few people declare this openly, usually in such cases, employees invent excuses or “forget” about the request.

Here, too, a number of defining motives can be identified:

- Competition: rivalry within the company reduces people's desire for cooperation. In such conditions, transferring resources to someone means losing the advantage and harming your team.

- Lack of stimulation: when people are rewarded only for achieving their goals, they begin to pay attention only to their own work. Motivation system "by performance" encourages hoarding.

- Big employment: workers may simply not have enough time and energy to help others. They have to choose between isolation and the prospect of not coping with their own responsibilities, being distracted by other people's problems.

- Fear of losing credibility: the more employees have some kind of knowledge or skill, the lower its specific value. Many fear that by passing their expertise to others, ultimately the company will not be needed.

3. Search Barrier

Here the snag is: the one who has the problem cannot find the one who has the solution. In contrast to the previous barriers, where people themselves do not seek interaction, the search barrier implies the impossibility to get in touch.

Barrier search occurs under the influence of the following factors:

- Company size: naturally, this problem occurs more often in large companies. The size is determined by the number and structure of business units, product line, subsidiaries and sales geography.

- Physical distance: people prefer to interact with those nearby. The likelihood of collaboration is inversely proportional to distance. The gap is observed even in cases where the workplaces of employees divide the distance of more than 25 meters. If teams are in different buildings, the chances are reduced even more, but if we are talking about offices in different countries, it is practically reduced to zero.

- Excess information: in an effort to provide people with access to the right data, management often goes too far. The necessary information is drowned in information noise, which significantly complicates the search.

- Weak networks: the world is not as small as is commonly believed. As a rule, only certain people have a wide network of contacts that help them quickly send a request in the right direction. The rest of the communication is weaker and the search for the right person takes a lot of time and effort.

4. Transmission barrier

In this case, the difficulty also lies not in unwillingness, but in the impossibility of establishing contact. Even highly motivated staff members often find it difficult to find a common language for various reasons.

Here are a few of them:

- Implicit knowledge: sometimes the type of information itself prevents direct transmission - not everything can be expressed in formulas or instructions. The process of communication is complicated when it comes to ambiguous, intuitive knowledge that is difficult to empirically substantiate (say, recommendations for negotiating).

- The lack of a common basis: you can not neglect the fact that unfamiliar people do not have an understanding of the usual style of work, forms of communication, the individual characteristics of the other side. All this seriously "inhibits" their interaction.

- Weak connections: the lack of strong relationships, a long experience of communication and leads to the fact that it is more difficult for employees to discuss subtle working issues and solve emerging problems.

From barriers to solutions

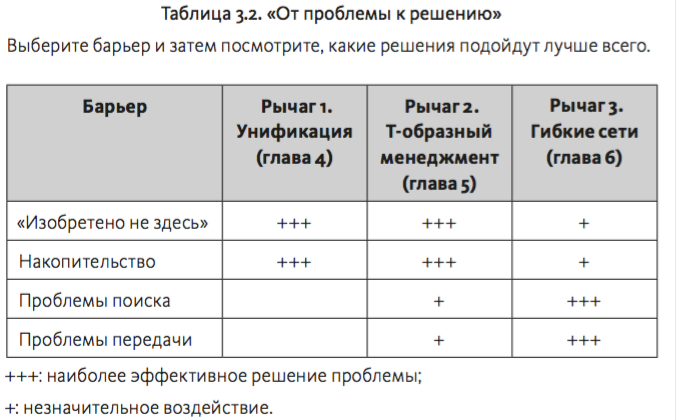

The first step is to pinpoint the barrier that is currently obstructing. The second step is the development of a management solution to eliminate each barrier. In general, the problems are related to the solutions proposed by the author as follows:

The first two barriers (“not invented here” and hoarding) concern the problems of motivation. From this it follows that management decisions should set people up to interact. This can be done in two ways.

- Bring people together: create a unifying goal, establish the fundamental value of teamwork, and use the leadership role to signal the start of interaction.

- Apply the system of T-shaped management: use recruitment, career promotion, dismissal and promotion to start a collaboration.

At the same time, the other two barriers — search and transmission — are related to the possibility of qualitative interaction. Overcoming these barriers has nothing to do with motivation. For them, there is only one effective solution: to build flexible networks, that is, to establish personal relationships between departments.

On this intriguing note, we will pause - the author gives a rather detailed description of each of these three methods; we intend to devote a separate post to them.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/359266/

All Articles