NIST finally changes password recommendations: now long passphrases are recommended

In the photo: Lorry Faith Kranor, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, in a dress with 500 of the most popular passwords on the Internet, at a summit on cybersecurity at Stanford University. She hopes that studying the dress will help other people to realize the need to change their weak password.

In the photo: Lorry Faith Kranor, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, in a dress with 500 of the most popular passwords on the Internet, at a summit on cybersecurity at Stanford University. She hopes that studying the dress will help other people to realize the need to change their weak password.In 2003, Bill Burr worked as a middle manager at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. He and his colleagues were instructed to write a boring instruction - a document with instructions for choosing and managing passwords, which was to become a recommendation for US government organizations. Employees completed the task - and this document became known as NIST Special Publication 800-63B . Personally, Burr wrote Appendix A to this standard (Appendix A) - an eight-page example that gives practical advice on choosing and managing passwords. Bill Burr recommended alternating numbers, special characters, lowercase and uppercase letters, as well as periodically changing passwords.

Over the years, the NIST recommendation has become a standard that has become mandatory for implementation in many state institutions, and the author himself is now fully aware of the scale of his mistakes and now regrets his deed, writes The Wall Street Journal .

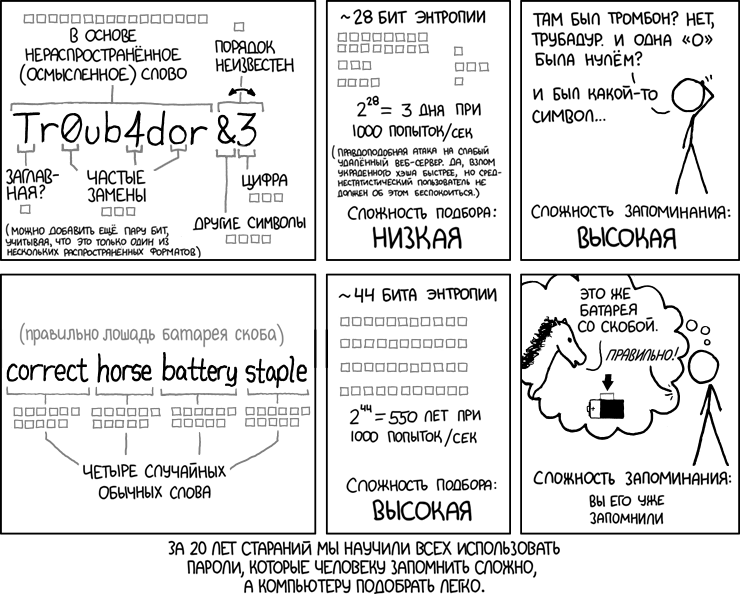

Absurd recommendations for choosing and managing passwords at one time became the plot of the famous comic strip XKCD .

')

It is unlikely that the manager of the National Institute of Standards and Technology could have imagined that his recommendations would become so widespread, become the absolute truth for millions of users and a huge number of companies, government agencies, educational institutions and others. They all set rules for selecting and managing passwords in accordance with NIST guidelines.

But over time, one problem manifested itself. It turned out that these recommendations are wrong, they do not contribute to improving computer security.

First, as noted above, they provide less entropy than long passphrases, and it is much more difficult to remember them. Try to remember a random set of characters in upper and lower case, mixed with numbers.

Secondly, the recommendation to change passwords every 90 days turned out to be particularly wrong. If a user can remember at least one complex password of letters with numbers, how can he change it after 90 days and remember a new password? As practice has shown, most people solve this problem in the most logical way: they make minimal changes to the password. For example, they simply change the last digit by adding one: Pa55word! 1, Pa55word! 2, Pa55word! 3, and so on. This does not contribute to increased safety at all.

Now Mr. Burr is 72 years old, he is retired. In the commentary of The Wall Street Journal, he said that he regretted most of the deed. Perhaps he does not need to be so strict with himself. Who would have thought that the recommendations of NIST would diverge so widely and become the “golden rules” for system administrators? In addition, at that time there was not enough academic research on password security, and it was difficult to write really competent recommendations, and the authorities were pressured by Burr demanding a quick finish. The specialist who programmed military mainframes during the Vietnam War simply did not have time to thoroughly study the topic. He even asked administrators to give him a look at the real passwords of NIST employees for analysis, but he was surprised to be denied for reasons of protecting confidential data.

The administrators were surprised even by the request itself. Without empirical data, Burr was guided by the research of the 80s - this is the best that was found. As it turned out 15 years later, he made the wrong choice.

In June 2017, the two-year work on the processing of the NIST Special Publication 800-63B standard was completed. Initially, it was planned to restrict ourselves with light fixes, but in the end, a group of employees had to rewrite everything from scratch. In the new rules there is no mandatory requirement to use special characters (such as question marks and exclamation marks) and there is no requirement for a mandatory password change.

Now finally, the entropy rules from the Munro comic come to the NIST experts - and the updated standard recommends using long passphrases , easy to remember, but difficult for bruteforce.

Changing passwords is now recommended only if there is a possibility of compromise, that is, if there are signs of leakage.

Well, finally justice triumphed. What many security experts said was officially recognized at the NIST level. Millions of users who stupidly changed passwords every three months, choosing lowercase and uppercase letters, numbers and special characters, intuitively felt the absurdity of this process - and now they too can breathe a sigh of relief. New rules involve the use of passphrases, which are much easier to remember. These can be lines from a poem or arbitrary sentences. To brute-force 40-character phrases, hackers will have to use new dictionaries with word compatibility graphs. This is more difficult than truncating an eight-character password with arbitrary characters.

Researchers say that even a phrase of four arbitrary words provides a high enough level of security to reliably protect against brute force.

All users spend every day about 1300 years on typing passwords, so the correct recommendations are very important. With passphrases, the time consumption of humanity, however, will increase even more. But the entropy of passwords will increase, more importantly.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/357406/

All Articles