Web application security: fighting with oneself, or drawing the line of adequacy

How safe should the application be? For some, this question does not make sense. "As much as possible. The safer the better." But this is not an exhaustive answer. And it does not help to form a security policy in the project. Moreover, if we follow only this directive (“the more security, the better”), we can do a disservice to ourselves. Why? The answer is under the cut.

Security conflicts with usability

Extra security checks make the application less convenient. This mainly affects 2 parts of the application: password authentication and recovery.

Multi-factor authentication, which includes sending SMS and entering additional data in addition to a password, makes the life of users a little more secure, but less happy. And if the whole essence of your service is that there you can exchange pictures with cats, then the user may not appreciate your desire to make his experience more secure.

Best Security Practices recommend that in case of authentication errors, we should give the user as little information as possible about where the error could occur, so that an attacker could not build a user base. According to these recommendations, if a site visitor went through 33 authentication steps and made a typo in one of the fields, the best security solution would be to write a neutral message: "Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again." Thanks to the developers and sincere admiration for the noble intentions of the site security system - these are not the emotions that the user will have in this case.

It is necessary to clearly understand in what cases and how much the user experience deteriorates when introducing certain safety practices. And decide whether it is needed specifically for your application.

Security makes the application harder to develop and maintain

The more security an application implements, the more difficult it is to develop. The duration of writing a separate functionality can grow several times for the sake of minor security improvements.

Many activities can be spent not on actual protection from vulnerabilities, but on making the life of cybercriminals more miserable. As an extreme example of this case, we can cite the obfuscation of the names of the REST API methods and their parameters.

Often, developers devote a lot of time to an attacker not being able to collect a database of user names through the login form, registration or password recovery.

You can meet the approaches when the application marks the user as an attacker, but does not give out information about it. User requests are just ignored.

If multifactor authentication includes a “secret question” that is unique to each user, then for a non-existent username, the application can still display the secret question. Moreover, the web application can store in the session or in the database the name of this nonexistent user and the question that was shown to him for the first time in order to consistently ask for the same information.

There are hundreds of other ways to confuse the attacker. But, of course, they require time for implementation. These mechanisms can be quite complex to understand and maintain, even with good code and accompanying comments. But the most important thing is that these things do not close any vulnerabilities, but are done solely in order to impede the search for these very vulnerabilities.

It is not always easy to separate "Competently designed and safe functionality" from "Crazy mind games with an imaginary hacker." Moreover, this border floats depending on how your application attracts potential intruders.

Security makes the application harder to test

All our rules and checks should be tested. Unit tests, integration tests, manual testing - we need to decide which approach will be used for each specific security mechanism.

Just do not test, we can not. Because in the code errors creep in. And even if we initially wrote everything without errors, then in the process of support, modification, refactoring - errors will definitely appear. No one writes legacy code right away. It becomes legacy code gradually.

It would not be entirely reasonable if the business functionality is thoroughly tested, but security mechanisms are considered indestructible, flawless and absolute.

If this is all manually tested, then the question is how often. If we have a more or less complex web application that uses the REST API, then there are potentially dozens, if not hundreds, of places where a broken authentication vulnerability could creep in. A typical example of a vulnerability is when we change a parameter (for example, a user ID) to another in an HTTP request and return information to which we should not have access. To check every case like this is a titanic work. Do I have to do this before every major release? Do I need to allocate for this individual? Or a separate team?

These questions are important because broken authentication is very easy to allow. For any change in the model, for any new REST method, you should always think about whether this vulnerability will appear. There is no universal and simple solution. But there are various approaches that allow the project to deal with the problem consistently. For example, in our CUBA platform, we use roles and access groups that allow us to customize which entities are available to whom. There is still a lot of work on setting up the rules, but these rules are uniform and consistent, which facilitates support.

In addition to broken authentication, there are dozens of security problems that are also advisable to check. And, introducing new checks and mechanisms, we need to think about how it will be tested. Things that are not tested, tend to break down over time. And then we have enough of not having normal security, so there will also be a false assurance that it is.

Particular problems are delivered by 2 categories of defense mechanisms: those that are included only for production, and those that constitute the protection of the second (third, fourth) level.

Protection that is implemented only in production. Suppose a session token cookie must have the https checkbox. But, if http is used on the testing environment, this means that there are separate configurations for testing and production. Consequently, it is not quite tested what they will use. And, if during the migration or any changes this tick is no longer placed, we can not immediately notice. How to solve this problem? Introduce another environment for pre-production? If so, what part of the functionality to test on it?

Multi-level protection. People tempted by security like to create a protection that can be tested only if the first barrier broke. The idea is reasonable. Even if an attacker found vulnerability in the first echelon, he will be stuck on the 2nd. But how to test it? A typical example is the use of different db users for different users of an application. Even if our REST contains broken authentication, then the attacker will not be able to edit / delete the data, because his db user will not have rights. Of course, these configurations become obsolete, break if they are not maintained and tested.

A lot of security can make an application less secure

The more security checks, the greater the complexity. The greater the complexity, the greater the likelihood of making a mistake. The more likely to make a mistake, the worse security.

Take for example the login form again. Login with two fields (username and password) is simple to implement. You just need to check if there is such a user in the system and if the password is entered correctly. Well, it is also necessary to check that the login / password is in the request body, and not in the URL parameters. It is advisable to make sure that the application does not suggest where there is an error in the login or password - so that it is impossible to build a database with a list of users (this item can be ignored for some applications in the name of a better user experience). And be sure to make sure that the anti-bruteforce mechanism is implemented. Which, of course, must be resistant to fail-open vulnerabilities. Even better, if we don’t show the hacker that we’ve marked him as a “hacker” and just start ignoring his requests, let him continue to think that he is hacking the login. Yes, and we must not forget to make sure that we do not write the transmitted password anywhere in the logs. Well, and a few subtleties that need to be remembered. In general, what could be simpler than the usual login form with two fields?

Another thing is multifactor authentication. Where we send some kind of token to the mail or by SMS. Or where you need to enter some additional data. Or you have to go through a number of steps, gradually entering information about yourself. All this is difficult. In theory, all these additional checks should reduce the likelihood of hacking. If everything is implemented correctly, then this is true. The likelihood of hacking remains (neither SMS, nor e-mail messages, nor anything else gives a 100% guarantee against hacking), but decreases. But the already rather complex authentication logic becomes even more complex, and somewhere to make a mistake becomes easier. The presence of at least one mistake or one wrong assumption makes the whole model less securious than a simple form with 2 fields.

Moreover, annoying and inconvenient security measures may force users to keep their information less secure. For example, if in a corporate network you need to change your password every month, then users who are absolutely incomprehensible to these strange requirements can simply start writing their password on a sticker and glue it to the monitor. “This is a problem for users if they make such a stupid mistake” - you might argue. But no. This is our problem with you. In the end, isn't it for these users that we make our applications?

Wonderful. What do you suggest?

I suggest from the very beginning of development to determine how far we are ready to go to deceive the attacker. Are we ready to optimize our login form so that the response time to the login request will never tell if there is a user with that name or not? Are you ready to implement such checks during authentication, that even a friend of a victim of hacking with her phone in her hands and from her computer is not able to enter our application? Are we ready to complicate development at times, significantly increase the budget and development time, sacrifice good user experience in order to make the attacker's life a little more difficult?

You can endlessly work on security, erecting new levels of protection, improving monitoring and analysis of user behavior, making it difficult to obtain information. There must be a line that separates us from what should be done and what should not be done. Of course, in the course of the project development, this feature can be rethought and changed.

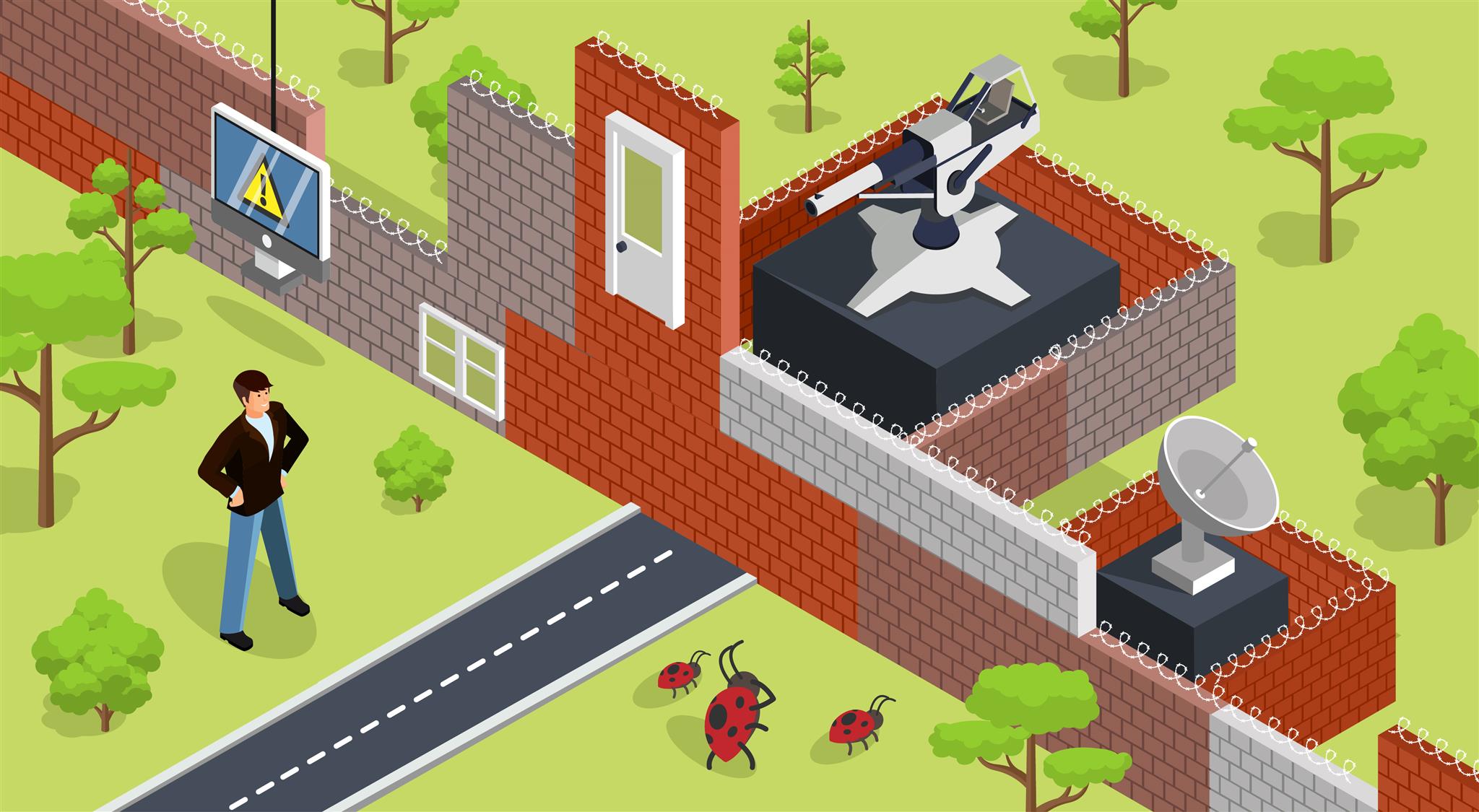

In the worst case, a project can spend a lot of resources on building an impenetrable wall against one type of attack, when there is a huge security breach in another application.

When making a choice, whether we will work on this or that security mechanism, or whether we will configure another level of protection, we must take into account many factors:

- How easy is a vulnerability to exploit? Broken authentication is very easy to use and does not require a technical background for this. Therefore, we must pay considerable attention to this issue.

- How critical is vulnerability? If an attacker gains access to the information of other users or can change the information of other users, then obviously this is a very important problem. If an attacker can collect IDs of certain products in our system, but has no way to do anything with these IDs, then the importance of the problem is several times lower.

- How much will the security of the site increase if we implement it? If this is not about the first level of protection (for example, checking XSS problems on an input, when a good mechanism for sanitizing an output is already implemented) or it is simply that confusing the attacker more (instead of blocking his actions, we start to ignore his requests, "pretending "that we did not recognize the attack), - the priority of these changes is not very high, if they should be implemented at all.

- How long will it take / will it cost?

- How much will the user experience worsen as a result of this change?

- How difficult will it be to maintain and test? It is common practice not to use code 403 when trying to access a forbidden resource, but always to return 404 to make it difficult to gather information about existing identifiers. This solution, although it makes sense and really makes an attacker’s life more difficult, at the same time can complicate testing, analysis of production errors and even affect the positive user experience when instead of telling them that they have not enough rights to get it resource, we say that such a resource is not in principle.

Yes. In your particular case, complex multifactor authentication may be necessary. But you should be aware of how difficult it is to support and develop it and how much it makes your application less enjoyable for users.

You excuse disregard for security

No way. There are security-sensitive applications where additional protection may be needed even to the detriment of user experience and development costs.

Well, in any case, there are a number of vulnerabilities that are not allowed to have, no matter what the application is intended for. CSRF is an example of such a vulnerability. The fight against it definitely does not make the user experience worse and does not greatly complicate the development. Many server-side (for example, Spring MVC) and client-side (for example, Angular) frameworks make it easy to support CSRF tokens out of the box. Further, using the same Spring MVC, adding several necessary headers (Access-Control- * headers, Content-Security-Policy) is also a fairly simple task.

Broken authentication, XSS, SQL injections and some other vulnerabilities can not be in your applications. Protection against them is easy to understand and is dismantled on the shelves in numerous books and articles. Passing sensitive information in URL parameters or storing weakly hashed passwords are included here.

Ideally, the project should have a manifest that regulates security policy: what and how to protect, description of password policy, what is being tested, etc. This manifest will be different for different projects. Projects where there is an insertion of user input into the command of the operating system will contain a description of protection against injection OS commands. Projects where the user can upload his files to the server (including the avatar) require a description of the basic vulnerabilities that may appear in this case.

Of course, writing and maintaining such a manifest is not an easy task. But hoping that every member of the team (including testing and support teams) will remember which practices to follow in the project, and will consistently and consistently implement them, is naive. In addition, the problem is that for many vulnerabilities, there are several prevention options. And in the absence of a clearly defined policy, there may be a situation where in some places one practice is used (for example, validation of input parameters), and in the other - the opposite (for example, validation of output parameters). In some places, sanitization will be used, and in part - the initiation of validation errors. And even if these different mechanisms are implemented very well, inconsistency is an excellent basis for the emergence of bugs, the difficulty of support and the formation of false expectations about the work of the code.

If the team is small and the technical manager is unchanged and has a developed security policy, then a permanent code review may be sufficient to avoid such problems even without a manifest.

Findings:

- When working on security, you need to consider how sensitive the site is to security. Applications for banks and an application for publishing jokes require different approaches.

- When working on security, you need to consider how much the user experience will deteriorate as a result of this or that change.

- When working on security, you need to consider how much this solution will make the code more complicated and more painful support.

- Security mechanisms need to be tested.

- In the team, it is desirable to introduce educational activities on security issues and / or expose the whole work to a thorough security review.

- There are vulnerabilities that it is desirable to get rid of for web applications of any level: xss, xsrf, injections (including SQL), broken authentication, etc.

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/354992/

All Articles