Marvin Minsky "The Emotion Machine": Chapter 3 "The Pain"

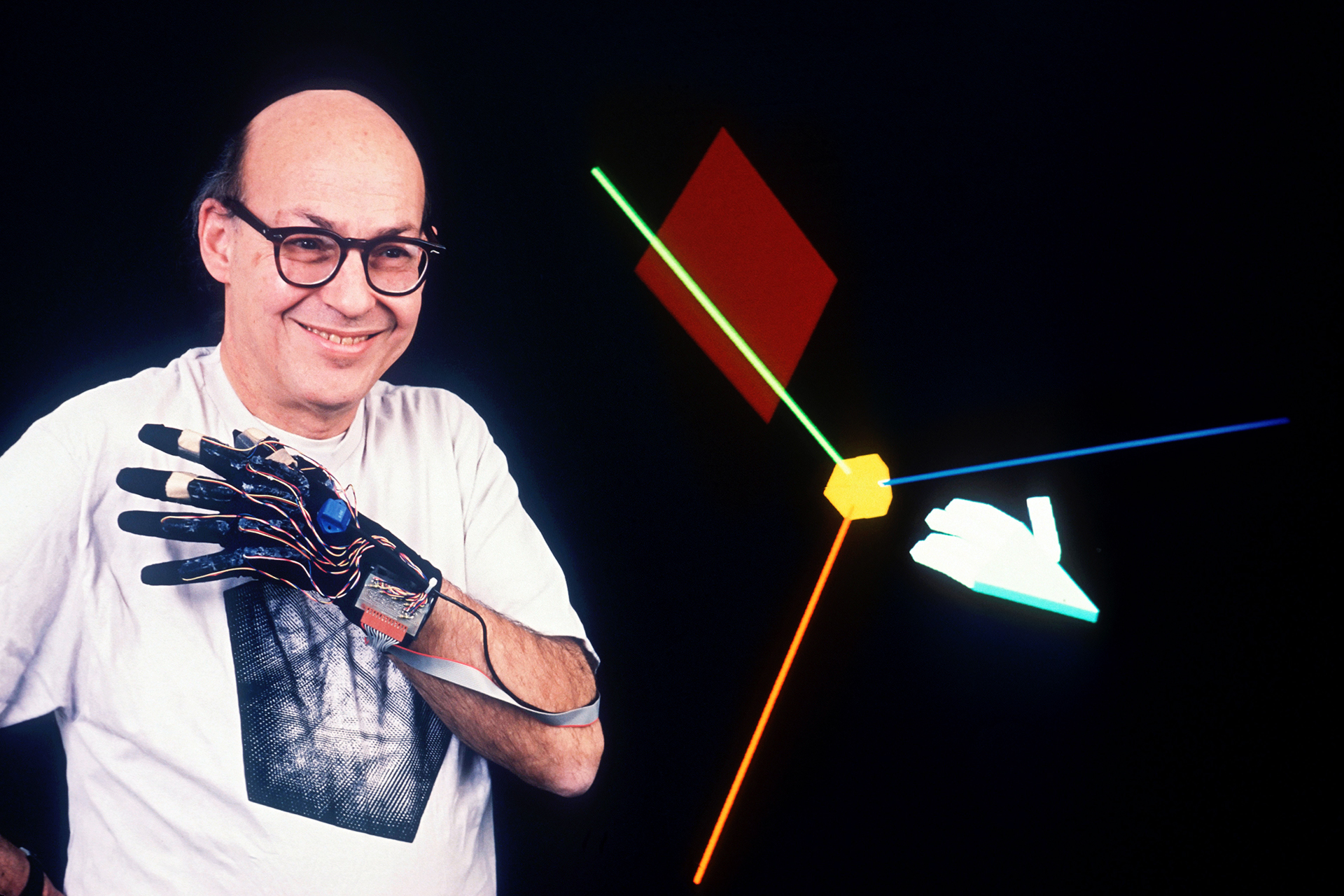

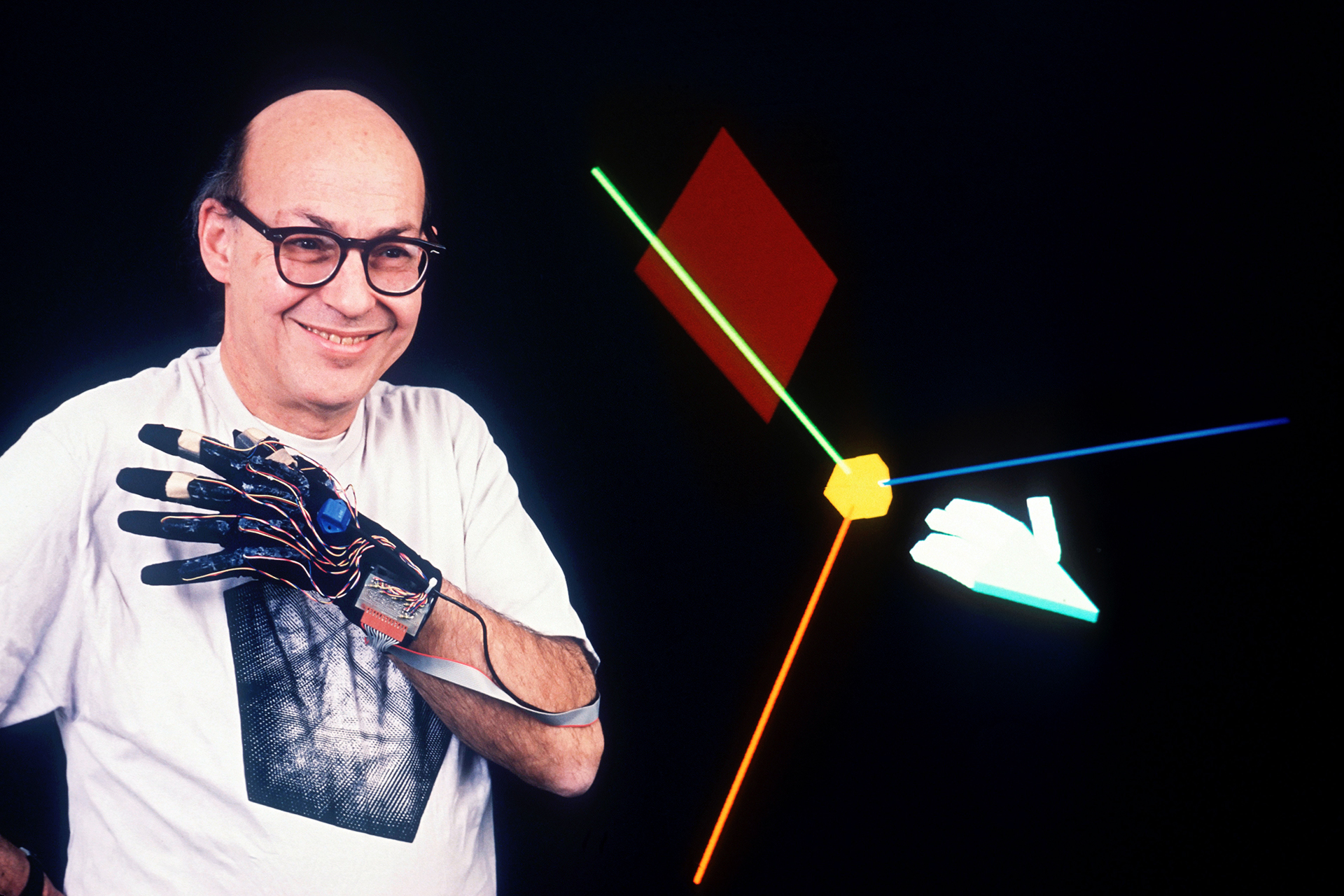

The father of artificial intelligence is thinking about how to make a machine that would be proud of us . Marvin Minsky was a rather tough scientist and the fact that he explored the theme of feelings and emotions with his “scalpel of knowledge”, which makes us human, is quite interesting and useful. The book is an excellent example of how to use the “ITish approach” to try to comprehend the “human”: values, ideals, love, pain, common sense.

Why does the sensation we call pain sometimes lead to what we call suffering? How can such an insignificant event affect all other thoughts so strongly? This chapter proposes the following hypothesis: if the pain is sufficiently intense and does not subside, the brain will attract additional resources to solve the problem, and those, in turn, will attract more. Further, if such dynamics continue, the mind will become a victim of a large-scale “cascade” that will eventually absorb it completely, as described in Section 1-7:

Sometimes pain is just pain; if she is not too intense and long, she will not bother you too much. Even if the pain is acute, you can usually numb it for a while, trying to think about something else. Finally, you can ease the pain by thinking about it yourself — by focusing on it, assessing its intensity, trying to view its shades as interesting innovations.

')

And yet, we should be glad that the pain "survived" in the framework of the evolutionary process - it protects our bodies from damage. First, according to Darwin, pain can cause you to shake off the irritant - it can keep you from trying to move the damaged part of the body, allowing it to rest and heal. Here are other ways in which pain protects us from injury:

But instead of being grateful for the pain, we only complain about it. “Why are we cursed at these terrible sensations?” The victims of pain ask. We often think of pain and pleasure as opposites - but they are united by many properties:

It can be assumed that pleasure and pain involve the same “mechanisms”. For example, both narrow our range of attention, both relate to how we absorb information, and both give priority to only one of many human goals. Given these similarities, it is easy to imagine that a reasonable newcomer may wonder why people love pleasure so much, but try to avoid pain:

Alien: Why do people complain of pain?

Man: We don't like pain because it hurts.

Newcomer: Explain what it means to "hurt"?

Man: It hurts when we feel pain.

Newcomer: Please explain what a “feeling” is?

At this point, the conversation may come to a standstill, since many human thinkers believe that we can never explain such things - because the feelings are “irreducible”.

Dualist philosopher: Science can only explain a phenomenon with other, simpler phenomena. But subjective feelings, such as pleasure and pain, are by definition irreducible (they cannot be simplified). They cannot be divided into the simplest parts, such as atoms: either they are or they are not.

This book describes the opposite view of feelings, not as simple, “irreducible” phenomena - as extremely complex, complex phenomena. And, somewhat paradoxically, as soon as we recognize this complexity, we can explain why pleasure and pain are similar, presenting (which we will try to do in Chapter 9) both feelings as the results of the work of similar “mechanisms”.

People often use the word "pain", the concepts of "pain" and "suffering" as if they describe the same condition, and differ only in severity. This chapter presents an alternative point of view: that we need significantly more pronounced differences and separate theories for each of these phenomena.

Our idea of the work mechanism of Suffering is this: any acute and prolonged pain leads to a cascade of mental changes that have a devastating effect on your plans and goals. By suppressing the majority of other brain resources in this way, the process narrows your circle of interests - so that most of your mind obeys one irresistible team: Get rid of the Pain at any cost.

These mechanisms certainly have great value - provided that they force you to get rid of the irritant so that you can get back to business. However, if the intensity of the pain persists after you have done everything possible to get rid of it, it can continue to occupy the resources already allocated - and continue to “grab” new ones - until you lose the ability to “think about something other than it.” This spread may stop by itself, but until the pain disappears, the cascade can continue to grow and, as it absorbs new resources, it will decrease your ability to think, until it starts to seem that the remnants of your mind are sucked into a black hole of suffering. .

In such circumstances, your usual goals will seem much more difficult-achievable. Whatever you try to do, the pain will interfere with the process with your own requests and destroy your plans until the pain and trouble caused by it fill your mind, pushing out almost everything else. Perhaps the severity of suffering stems in large part from the inability to consciously choose what to think about. Suffering is a form of imprisonment.

Neurologist: Your assumptions about the destructive cascades are very tempting, but do you have any proof of the existence of such processes? How do you demonstrate your guesswork?

It will be impossible to demonstrate with today's technology, but when scanners can show what is happening in the brain with a higher resolution, we will most likely be able to see these cascades. For the time being, does someone need more substantive confirmation than complaints of the suffering:

Hence, it is possible to assume that we use such words as “suffering”, “longing” and “torture” in an attempt to describe what is happening to us when these destructive stages continue: as all new systems become frustrated and transmit alarm signals, your usual train of thought is so disturbed that it may seem as though your mind was “stolen”.

Citizen: I agree that all these emotions can accompany suffering. But this does not explain what suffering is. Certainly disgust, repentance, confusion and fear are associated with reactions to pain - and can make us suffer. But would it not be better to consider suffering just as another sensation?

As a rule, speaking of sensations, we mean signals from sensors that react to events in the outside world. However, we are talking here, it seems to me, about signals coming not from outside, from outside, but from special resources that track high-level states and stimuli [can be interpreted as: priority states] inside the brain. Later in section 4-3, we will assume exactly how these resources work.

Be that as it may, it is difficult for the suffering person to maintain a habitual way of thinking. So, being cut off from your usual thoughts, you find it difficult to talk about something other than the current state of burden - and awareness of your own plight only aggravates the problem. As mentioned above, pain deprives you of freedom, and a significant component of suffering is the despair of losing your freedom to make a mental choice. translator: by "mental choice" the author implies the freedom to consciously choose what to think about].

The same (although to a lesser extent) also applies to our ordinary states: our thoughts are always limited to actual goals, which, in turn, involve different processes. Sometimes these processes interact productively, but often they also collide and conflict. We never have enough time to do everything that we want to do - so, each new goal or idea can make us postpone or abandon other ambitions.

Most often, we do not pay much attention to these conflicts, because we feel that control is still in our hands, that we can make decisions ourselves - and if we are not satisfied with the result, we are still “free” to go back and try a different approach. But when pain interferes in the matter, all projects and plans are thrown away, as if by some external force - and then we come up with desperate ways to avoid pain. The urgency of the pain is useful when you have to deal with emergency situations - but if after that you cannot get rid of it quickly, the pain can turn into a catastrophe.

Indeed, suffering can affect you so much that friends will begin to see another person in your place. It may even make you fall so low that you will cry and beg for help, as if turning into a child. Of course, you may feel that you have not changed and still have your old memories and abilities. But you cannot use them productively until you return to your true identity.

The primary function of Pain is to make a person get rid of its source. However, to do this, she will have to undermine a person’s desire for most of his usual goals. When this leads to a vast cascade, we use words like “misery” to describe what remains of the mind of its victim.

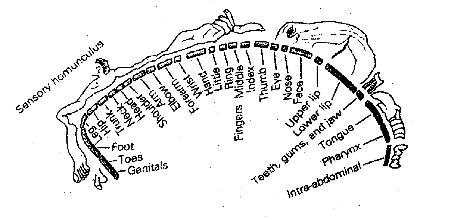

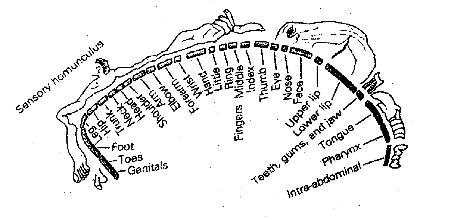

How does Joan know where her pain is concentrated? It turns out that it is very easy for her to tie a specific pain sensation to a specific place on the skin - she orients herself according to the innate “maps” of the skin integument located in different parts of her brain; similar to this, located in the sensory zone of the cortex.

Many brain tutorials state that these cards help us localize tactile sensations — but these tutorials do not explain the advantage of having these cards — given that skin could easily take over. However, to locate the internal foci of pain, we are far from doing so well. It seems that in the human brain there are no mechanisms that could localize the structure under the skin. Presumably, their maps were not preserved within the framework of the evolutionary process due to extremely low utility: there was no way, for example, to protect the spleen before the era of medicine, in addition to protecting the entire abdominal cavity - and therefore, a person needed only to know when his stomach hurt. In particular, we never say “My brain hurts terribly” because we never had any way to treat the brain, because of which the pain in the brain and the ability of spatial localization of mental events did not evolve.

Anyway, the pain Joan will be useful for her only if she forces her to focus on her knee - postponing, at the same time, her other goals. “Get rid of me,” inspires pain, “return to your Normal State.” Joan will not be able to return to working on the report until this requirement is met.

How does our sense of pain really work? Our scientists know at least a little bit only about a few events occurring in the first seconds after injury. First, damaged cells release substances that cause certain nerves to send signals to the spinal cord. Then certain neural networks send their own signals to the brain. However, our scientists are rather poorly aware of what happens after that in the rest of the brain. I have never seen a single worthy theory explaining why pain leads to suffering. Instead, you can find descriptions like the following:

Perhaps we will be able to find more clues about these things by exploring a rare disease that occurs as a result of damage to certain parts of the brain: the victims of Pain Asymbolism still feel what most of us call pain - but do not find these feelings unpleasant, and may even laugh at the answer to them. Perhaps they have lost some resources that cause the rest of us painful cascades.

Citizen: Physical pain is only one type of pain; emotional pain can be just as intense; at times they even lead people to suicide. Can your theory also explain this?

Is it possible that mental and physical pain are one and the same? You can often notice that they affect our mental states in a similar way. What could be the relationship between our reactions to, say, pinching or burning of the skin and “painful” internal experiences, such as

Imagine hearing Charles say, "I felt so restless and upset that something was tearing me apart from the inside." One could conclude that Charles' sensations reminded him of what he experienced with terrible abdominal pain.

Physiologist: Your feeling “as if you were torn apart from the inside” could be quite reasonable - your mental state could force the brain to send signals to the gastrointestinal tract.

In a similar way, we speak of “wounded feelings”, as if they resemble sensations of physical pain, despite the different circumstances of their occurrence. The reason may lie in the fact that those and other processes involve one type of high-level mechanisms. Thus, the disrespect of a comrade can disrupt the work of the brain just as badly as a deep, dull pain. And sometimes what begins with physical pain can be reinforced “psychologically”:

Student: Once, as a child, I hit my head on a chair and covered the damaged area with my palm. And although the pain was acute, it didn’t really upset me. Just seeing the blood on my arm, I panicked and burst into tears.

However, most of the senses are extremely difficult to describe, because we know very little about the mechanics of their work. However, it may be much easier to recognize the mental state (both in yourself and in others), since you only need to notice several criteria of a certain state. And this will most often be enough to help us communicate - we use the so-called “empathy”. Because to two minds that have structural similarities, it may be just a few clues to recognize the familiar signs in each other.

For the translation, thanks to Savva Sumin.

Marvin Lee Minsky (Eng. Marvin Lee Minsky; August 9, 1927 - January 24, 2016) - American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence, co-founder of the Laboratory of artificial intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Wikipedia ]

Interesting Facts:

3-1. Pain

“For countless generations, great pain has pushed animals to avoid suffering at the cost of the most bitter, most varied efforts. And even a person, feeling pain in a limb or another part of the body, is in the habit of shaking it, as if shaking off the cause of the pain, although it may obviously be impossible. ”What happens when you hit your big toe? You have not yet had time to fully feel the blow, but your breath is already lost, you start to sweat - because you know what follows the blow: terrifying pain, which twists the insides, forcing you to forget about all the goals, except one - to get rid of the pain .

- Charles Darwin.

Why does the sensation we call pain sometimes lead to what we call suffering? How can such an insignificant event affect all other thoughts so strongly? This chapter proposes the following hypothesis: if the pain is sufficiently intense and does not subside, the brain will attract additional resources to solve the problem, and those, in turn, will attract more. Further, if such dynamics continue, the mind will become a victim of a large-scale “cascade” that will eventually absorb it completely, as described in Section 1-7:

Sometimes pain is just pain; if she is not too intense and long, she will not bother you too much. Even if the pain is acute, you can usually numb it for a while, trying to think about something else. Finally, you can ease the pain by thinking about it yourself — by focusing on it, assessing its intensity, trying to view its shades as interesting innovations.

Daniel Dennett: If you manage to force yourself to study your pain (even very intense), you will find that you stop feeling it (there is no space for pain). However, studying pain (for example, headache) will bore you soon and, as soon as you stop studying it, it will return and “continue to hurt”, which, oddly enough, is often more interesting than studying a boring object and even in some way preferable.But this is only a temporary relief, because until the pain disappears, she will continue to nag and demand attention, as if an upset, unsatisfied child; you can think about something for a while, but no matter how hard you try, pain will soon dominate the mind again.

')

And yet, we should be glad that the pain "survived" in the framework of the evolutionary process - it protects our bodies from damage. First, according to Darwin, pain can cause you to shake off the irritant - it can keep you from trying to move the damaged part of the body, allowing it to rest and heal. Here are other ways in which pain protects us from injury:

- Pain focuses our attention on the affected part of the body.

- Pain prevents us from thinking about anything other than its source.

- Pain makes us avoid what causes it.

- It makes us strive to get out of the current state and teaches us not to return to it in the future.

But instead of being grateful for the pain, we only complain about it. “Why are we cursed at these terrible sensations?” The victims of pain ask. We often think of pain and pleasure as opposites - but they are united by many properties:

- Pleasure causes us to concentrate on certain parts of the body involved in the process.

- Pleasure makes it difficult to think about anything other than him.

- It forces us to get closer to its source.

- It encourages staying in the current state and teaches that in the future it is worth returning to it more often.

It can be assumed that pleasure and pain involve the same “mechanisms”. For example, both narrow our range of attention, both relate to how we absorb information, and both give priority to only one of many human goals. Given these similarities, it is easy to imagine that a reasonable newcomer may wonder why people love pleasure so much, but try to avoid pain:

Alien: Why do people complain of pain?

Man: We don't like pain because it hurts.

Newcomer: Explain what it means to "hurt"?

Man: It hurts when we feel pain.

Newcomer: Please explain what a “feeling” is?

At this point, the conversation may come to a standstill, since many human thinkers believe that we can never explain such things - because the feelings are “irreducible”.

Dualist philosopher: Science can only explain a phenomenon with other, simpler phenomena. But subjective feelings, such as pleasure and pain, are by definition irreducible (they cannot be simplified). They cannot be divided into the simplest parts, such as atoms: either they are or they are not.

This book describes the opposite view of feelings, not as simple, “irreducible” phenomena - as extremely complex, complex phenomena. And, somewhat paradoxically, as soon as we recognize this complexity, we can explain why pleasure and pain are similar, presenting (which we will try to do in Chapter 9) both feelings as the results of the work of similar “mechanisms”.

People often use the word "pain", the concepts of "pain" and "suffering" as if they describe the same condition, and differ only in severity. This chapter presents an alternative point of view: that we need significantly more pronounced differences and separate theories for each of these phenomena.

3-2. Prolonged Pain leads to Cascades

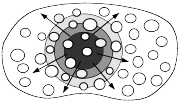

Our idea of the work mechanism of Suffering is this: any acute and prolonged pain leads to a cascade of mental changes that have a devastating effect on your plans and goals. By suppressing the majority of other brain resources in this way, the process narrows your circle of interests - so that most of your mind obeys one irresistible team: Get rid of the Pain at any cost.

These mechanisms certainly have great value - provided that they force you to get rid of the irritant so that you can get back to business. However, if the intensity of the pain persists after you have done everything possible to get rid of it, it can continue to occupy the resources already allocated - and continue to “grab” new ones - until you lose the ability to “think about something other than it.” This spread may stop by itself, but until the pain disappears, the cascade can continue to grow and, as it absorbs new resources, it will decrease your ability to think, until it starts to seem that the remnants of your mind are sucked into a black hole of suffering. .

In such circumstances, your usual goals will seem much more difficult-achievable. Whatever you try to do, the pain will interfere with the process with your own requests and destroy your plans until the pain and trouble caused by it fill your mind, pushing out almost everything else. Perhaps the severity of suffering stems in large part from the inability to consciously choose what to think about. Suffering is a form of imprisonment.

Neurologist: Your assumptions about the destructive cascades are very tempting, but do you have any proof of the existence of such processes? How do you demonstrate your guesswork?

It will be impossible to demonstrate with today's technology, but when scanners can show what is happening in the brain with a higher resolution, we will most likely be able to see these cascades. For the time being, does someone need more substantive confirmation than complaints of the suffering:

- Dissatisfaction with unmet goals.

- Irritation of loss of mobility.

- Annoyance of inability to think.

- The horror of becoming a helpless cripple.

- Shame from becoming a burden for friends.

- Repentance of unfulfilled obligations.

- The confusion of the probability of failure.

- Chagrin of their own "abnormality" in the eyes of others.

- Outrage from missed opportunities.

- Fear of the need for survival and the likelihood of death.

Hence, it is possible to assume that we use such words as “suffering”, “longing” and “torture” in an attempt to describe what is happening to us when these destructive stages continue: as all new systems become frustrated and transmit alarm signals, your usual train of thought is so disturbed that it may seem as though your mind was “stolen”.

Citizen: I agree that all these emotions can accompany suffering. But this does not explain what suffering is. Certainly disgust, repentance, confusion and fear are associated with reactions to pain - and can make us suffer. But would it not be better to consider suffering just as another sensation?

As a rule, speaking of sensations, we mean signals from sensors that react to events in the outside world. However, we are talking here, it seems to me, about signals coming not from outside, from outside, but from special resources that track high-level states and stimuli [can be interpreted as: priority states] inside the brain. Later in section 4-3, we will assume exactly how these resources work.

Be that as it may, it is difficult for the suffering person to maintain a habitual way of thinking. So, being cut off from your usual thoughts, you find it difficult to talk about something other than the current state of burden - and awareness of your own plight only aggravates the problem. As mentioned above, pain deprives you of freedom, and a significant component of suffering is the despair of losing your freedom to make a mental choice. translator: by "mental choice" the author implies the freedom to consciously choose what to think about].

The same (although to a lesser extent) also applies to our ordinary states: our thoughts are always limited to actual goals, which, in turn, involve different processes. Sometimes these processes interact productively, but often they also collide and conflict. We never have enough time to do everything that we want to do - so, each new goal or idea can make us postpone or abandon other ambitions.

Most often, we do not pay much attention to these conflicts, because we feel that control is still in our hands, that we can make decisions ourselves - and if we are not satisfied with the result, we are still “free” to go back and try a different approach. But when pain interferes in the matter, all projects and plans are thrown away, as if by some external force - and then we come up with desperate ways to avoid pain. The urgency of the pain is useful when you have to deal with emergency situations - but if after that you cannot get rid of it quickly, the pain can turn into a catastrophe.

Indeed, suffering can affect you so much that friends will begin to see another person in your place. It may even make you fall so low that you will cry and beg for help, as if turning into a child. Of course, you may feel that you have not changed and still have your old memories and abilities. But you cannot use them productively until you return to your true identity.

The primary function of Pain is to make a person get rid of its source. However, to do this, she will have to undermine a person’s desire for most of his usual goals. When this leads to a vast cascade, we use words like “misery” to describe what remains of the mind of its victim.

Mechanics of suffering

“The restless, fussy nature of nature is the root of pain, so I say. Find the peace of mind that rests in the pacification of immortality. Your “I” is only a pile of composite features, and his world is nothing more than an empty fantasy. ”

- Buddha.

"Life is full of grief, loneliness and suffering - and ends too quickly."Joan stumbled on the stairs yesterday. She did not have the slightest suspicion about the injury - but today she felt a terrible pain in her knee. She is working on an important report and plans to submit it tomorrow. “But if it continues,” she thinks, “I won’t even get to the place.” She tries to force herself to return to work, but soon she drops her pen and groans: "I need to get rid of this pain as soon as possible." In an attempt to get to the home first-aid kit and find a pill that can help a little, she suddenly feels a sharp, stabbing pain that makes her sit down and stop using her injured leg. She grabs her knee, tries to catch her breath and think about what to do next - but the pain subordinates her to herself so much that she cannot concentrate on anything else but her.

- Woody Allen.

How does Joan know where her pain is concentrated? It turns out that it is very easy for her to tie a specific pain sensation to a specific place on the skin - she orients herself according to the innate “maps” of the skin integument located in different parts of her brain; similar to this, located in the sensory zone of the cortex.

Many brain tutorials state that these cards help us localize tactile sensations — but these tutorials do not explain the advantage of having these cards — given that skin could easily take over. However, to locate the internal foci of pain, we are far from doing so well. It seems that in the human brain there are no mechanisms that could localize the structure under the skin. Presumably, their maps were not preserved within the framework of the evolutionary process due to extremely low utility: there was no way, for example, to protect the spleen before the era of medicine, in addition to protecting the entire abdominal cavity - and therefore, a person needed only to know when his stomach hurt. In particular, we never say “My brain hurts terribly” because we never had any way to treat the brain, because of which the pain in the brain and the ability of spatial localization of mental events did not evolve.

Anyway, the pain Joan will be useful for her only if she forces her to focus on her knee - postponing, at the same time, her other goals. “Get rid of me,” inspires pain, “return to your Normal State.” Joan will not be able to return to working on the report until this requirement is met.

How does our sense of pain really work? Our scientists know at least a little bit only about a few events occurring in the first seconds after injury. First, damaged cells release substances that cause certain nerves to send signals to the spinal cord. Then certain neural networks send their own signals to the brain. However, our scientists are rather poorly aware of what happens after that in the rest of the brain. I have never seen a single worthy theory explaining why pain leads to suffering. Instead, you can find descriptions like the following:

The feeling of pain arises as a result of the reaction of certain nerves to high temperatures, pressure, etc. Then their signals rise to your thalamus, from which signals are also sent to other areas of the brain - provoking processes that at different levels include hormones, endorphins and neurotransmitters. Reaching your limbic system, they provoke such emotions as sadness, anger and frustration.But this explanation is not enough, because to understand the nature of suffering is not enough understanding of which areas of the brain are involved in the process. You also need to understand the functions of these zones and how each of them affects the rest; both during the stay of the object in its usual state, and during the above-mentioned cascades (in order to better understand the characteristics of suffering). Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall, one of the first to study the problem of pain, carefully note:

“A certain zone of the anterior cingulate layer of the cerebral cortex has a highly specialized function in the treatment of pain sensations, corresponding to involvement in the characteristic emotional-motivational component of pain.”However, we also know that pain affects many other areas of the brain. Melzac and Wall continue:

“The concept of a“ pain center ”is pure fantasy, unless you consider the whole brain as this center; because the thalamus, the limbic system, the hypothalamus, the reticular substance of the brain stem, the parietal and frontal zones of the cortex are all involved in the perception of pain. "Also, our reactions to pain depend on the following mental states:

Daniel Dannet: “The real pain is connected with the impulse to survival, with the real probability of death, with the ailments of our soft, vulnerable, warm flesh. [...] It is impossible to deny (although the experience of many shows the possibility of ignoring) that our concept of pain is inextricably linked to our ethical perception, our sufferings, responsibilities and evil. ”Generally speaking, we do not know so much about how physical pain leads to suffering. And although we were able to localize many of the related processes within the brain, we practically do not understand how each corresponding zone works - because for this we need theories (like those outlined in this book) about what exactly they do.

Perhaps we will be able to find more clues about these things by exploring a rare disease that occurs as a result of damage to certain parts of the brain: the victims of Pain Asymbolism still feel what most of us call pain - but do not find these feelings unpleasant, and may even laugh at the answer to them. Perhaps they have lost some resources that cause the rest of us painful cascades.

Physical pain versus mental “pain”

Citizen: Physical pain is only one type of pain; emotional pain can be just as intense; at times they even lead people to suicide. Can your theory also explain this?

Is it possible that mental and physical pain are one and the same? You can often notice that they affect our mental states in a similar way. What could be the relationship between our reactions to, say, pinching or burning of the skin and “painful” internal experiences, such as

- The pain of losing a friend.

- The pain of seeing the pain of other people.

- Pain from sleep deprivation.

- The pain of humiliation and foreseeable failures.

- Pain from excessive and prolonged stress.

Imagine hearing Charles say, "I felt so restless and upset that something was tearing me apart from the inside." One could conclude that Charles' sensations reminded him of what he experienced with terrible abdominal pain.

Physiologist: Your feeling “as if you were torn apart from the inside” could be quite reasonable - your mental state could force the brain to send signals to the gastrointestinal tract.

In a similar way, we speak of “wounded feelings”, as if they resemble sensations of physical pain, despite the different circumstances of their occurrence. The reason may lie in the fact that those and other processes involve one type of high-level mechanisms. Thus, the disrespect of a comrade can disrupt the work of the brain just as badly as a deep, dull pain. And sometimes what begins with physical pain can be reinforced “psychologically”:

Student: Once, as a child, I hit my head on a chair and covered the damaged area with my palm. And although the pain was acute, it didn’t really upset me. Just seeing the blood on my arm, I panicked and burst into tears.

However, most of the senses are extremely difficult to describe, because we know very little about the mechanics of their work. However, it may be much easier to recognize the mental state (both in yourself and in others), since you only need to notice several criteria of a certain state. And this will most often be enough to help us communicate - we use the so-called “empathy”. Because to two minds that have structural similarities, it may be just a few clues to recognize the familiar signs in each other.

For the translation, thanks to Savva Sumin.

Table of Contents of The Emotion Machine

Introduction

Chapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

Chapter 1. Falling in Love

Chapter 2. ATTACHMENTS AND GOALS

Chapter 3. FROM PAIN TO SUFFERINGChapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

about the author

Marvin Lee Minsky (Eng. Marvin Lee Minsky; August 9, 1927 - January 24, 2016) - American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence, co-founder of the Laboratory of artificial intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Wikipedia ]

Interesting Facts:

- Minsky was a friend of critic Harold Bloom from Yale University (Yale University), who spoke of him as “sinister Marvin Minsky”.

- Isaac Asimov described Minsky as one of two people who are smarter than himself; the second, in his opinion, was Karl Sagan.

- Marvin is a robot with artificial intelligence from the cycle of Douglas Adams novels Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (film).

- Minsky has a contract to freeze his brain after death in order to be “resurrected” in the future.

- In honor of Minsk named the dog of the protagonist in the movie Tron: Legacy. [ Wikipedia ]

About #philtech

#philtech (technology + philanthropy) is an open, publicly described technology that aligns the standard of living of as many people as possible by creating transparent platforms for interaction and access to data and knowledge. And satisfying the principles of filteha:

1. Opened and replicable, not competitive proprietary.

2. Built on the principles of self-organization and horizontal interaction.

3. Sustainable and prospective-oriented, and not pursuing local benefits.

4. Built on [open] data, not traditions and beliefs.

5. Non-violent and non-manipulative.

6. Inclusive, and not working for one group of people at the expense of others.

Philtech's social technology startups accelerator is a program of intensive development of early-stage projects aimed at leveling access to information, resources and opportunities. The second stream: March – June 2018.

Chat in Telegram

A community of people developing filtech projects or simply interested in the topic of technologies for the social sector.

#philtech news

Telegram channel with news about projects in the #philtech ideology and links to useful materials.

Subscribe to the weekly newsletter

#philtech (technology + philanthropy) is an open, publicly described technology that aligns the standard of living of as many people as possible by creating transparent platforms for interaction and access to data and knowledge. And satisfying the principles of filteha:

1. Opened and replicable, not competitive proprietary.

2. Built on the principles of self-organization and horizontal interaction.

3. Sustainable and prospective-oriented, and not pursuing local benefits.

4. Built on [open] data, not traditions and beliefs.

5. Non-violent and non-manipulative.

6. Inclusive, and not working for one group of people at the expense of others.

Philtech's social technology startups accelerator is a program of intensive development of early-stage projects aimed at leveling access to information, resources and opportunities. The second stream: March – June 2018.

Chat in Telegram

A community of people developing filtech projects or simply interested in the topic of technologies for the social sector.

#philtech news

Telegram channel with news about projects in the #philtech ideology and links to useful materials.

Subscribe to the weekly newsletter

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/354724/

All Articles