Solar JSOC Forensics: mining case on 32 non-existent hypervisors

The last year can be considered the heyday of mass mining cryptocurrency. Exactly a year ago, this HYIP reached its peak, and the prices for video cards in the stores soared. Then the mining algorithms were ported to browsers, and the famous service Coinhive appeared. Even the recent fall in the rate of the main cryptocurrency did not slow down the process much. Naturally, the attackers not only watched this phenomenon, but took an active part in it.

You can have different attitudes to the cryptocurrency and tokens themselves, however, every security person has a negative attitude towards mining when it is performed unauthorized and on the equipment of the enterprise. We recorded and investigated many incidents where external violators spread miners into the load to the main malware module, hide it under the names of system processes (for example, C: \ Windows \ Sys \ taskmgr.exe), and sometimes there were cases when account network exploits, Psexec-ov and their analogues, and of course, malicious Javascript.

But, apart from the external violator, there is an internal violator. And more often he knows well what he is doing and how to hide the traces so as to go unpunished. One such case was asked to investigate.

')

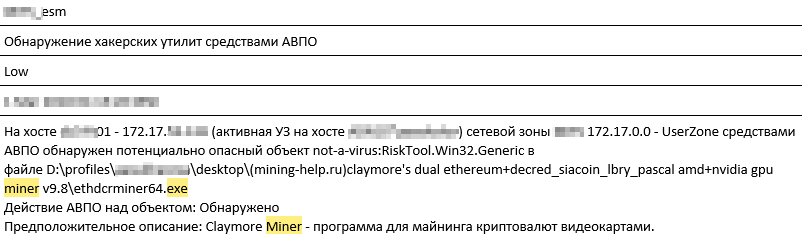

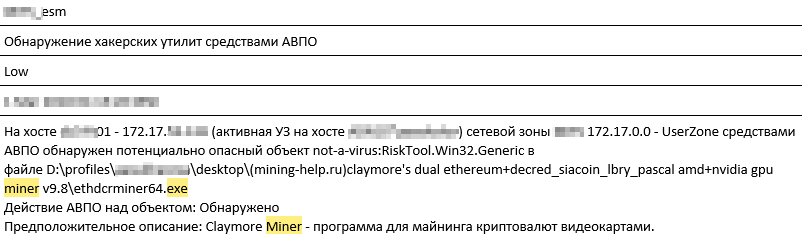

Sometimes it is enough to look at the SIEM logs to understand who launched the miner: the following screenshot shows that the miner’s executable file was unpacked to the desktop of one of the server users:

Hypothesis 0. The employee did it deliberately, since the file is unpacked to the desktop. The likelihood that this made malware is minimal.

It is very easy to test such a hypothesis - just look at the antivirus log in the user's workplace. Surely the same rule previously worked on the archive, lying in the \ Downloads folder.

However, not always, looking at the journals in the SIEM, it turns out to establish who is the insider who violates the security policy of the enterprise. In such cases, incidents are transmitted to Solar JSOC CERT.

As part of the provision of Solar JSOC services, there is a high-level entity — a monitoring scenario. It describes what incidents we are committed to identifying and how different monitoring lines should respond to them. Naturally, all customers are different, and each has its own set of scenarios, which are periodically reviewed and changed.

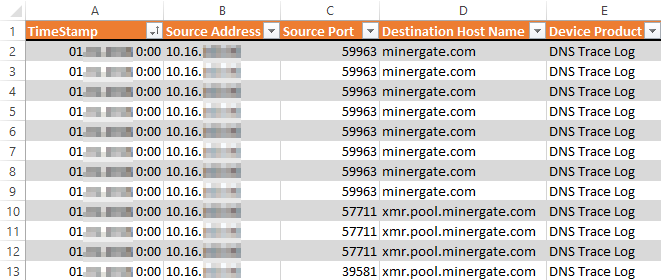

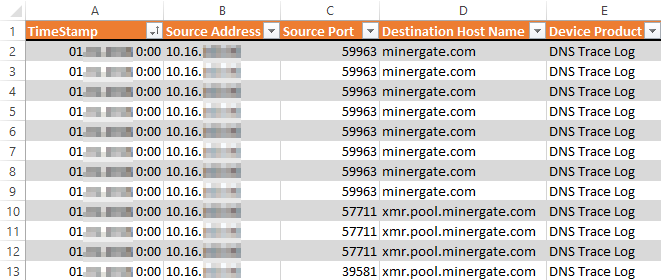

One afternoon, our colleagues connected a large client with a new scenario — the discovery of mining activity. 10 seconds after the inclusion of the rule set in the SIEM, we began to fix multiple DNS queries to the addresses of one of the mining pools.

An analyst on the part of Solar JSOC informed the client about “potentially undesirable activity”, and he blocked the calls on the firewall and proxy server. Worked out properly, and everything seems to be fine, and you can go on. But at the same time, the analyst also drew attention to the fact that mining was carried out from 32 different IP addresses, which, according to the documents, are hypervisors (and their capacities are considerable). We immediately reported this to the customer, who asked for a detailed investigation of the incident.

As soon as the case was transferred to JSOC CERT, we immediately began collecting digital evidence (hard drive copy, RAM, etc.), and then two unpleasant circumstances stood in the way of the investigation:

At first, we proposed to disable the lockout of domain names of the mining pool in order to catch the attacker "on the bait," but after disabling the lock, activity did not resume. Apparently, the attacker realized that they learned about his activities, and turned off the miners.

Hypothesis number 1. An attacker could be someone of their own.

We are going to the data center to remove data on the spot. There we are shown empty racks and dumped demagnetized hard drives. Data center employees also worked out regularly: for information security, when dismounting hypervisors, the disks should be demagnetized, which was actually done 2 months ago - even documents with a seal confirmed this.

Hypothesis No. 2. Data center employees are involved in the incident.

As a result, we have an unpleasant situation when there are no target servers, the logs of their domain controller are erased (remember, this segment is not connected to SIEM), Internet access from the segment is not proxied, no netflow and no mention ... At such times, you should take a step back and remember what we have. And we only had DNS server logs ...

In cases when it is necessary to analyze a very large log, each incident response specialist uses “his own” utilities:

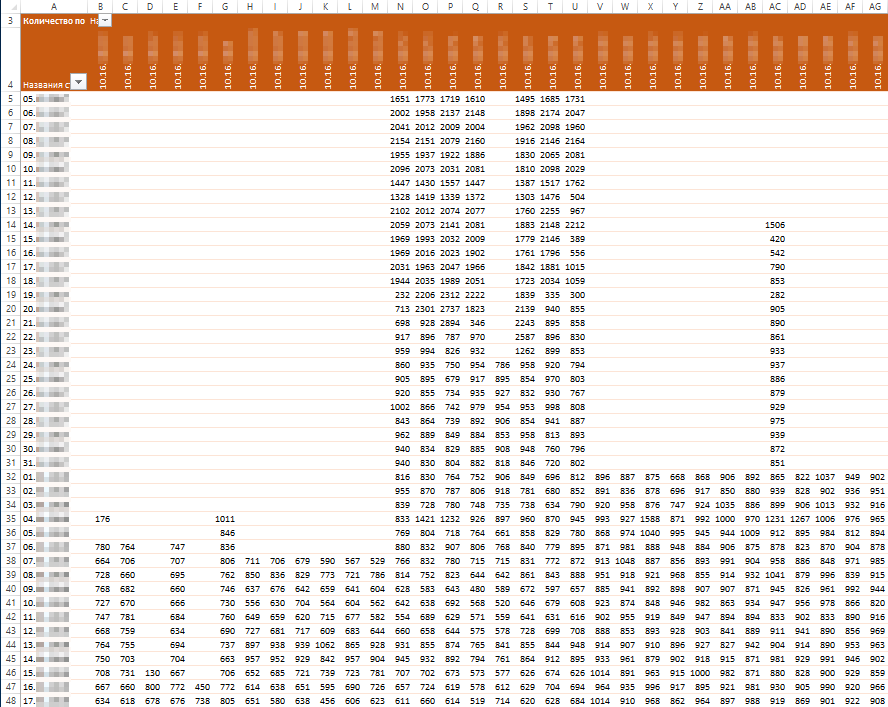

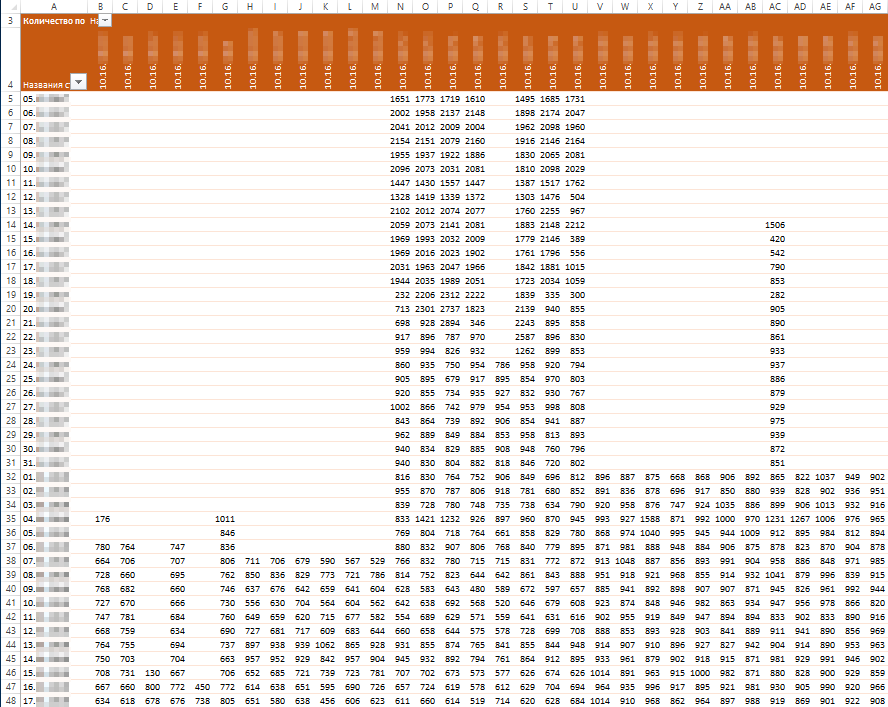

We use all of the above and even more, but in this case, the statistical analysis made in good old Excel, namely pivot tables, which convert a million of such records in a couple of clicks, was most obvious:

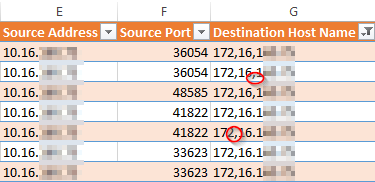

HPE ArcSight sample upload

in such a table:

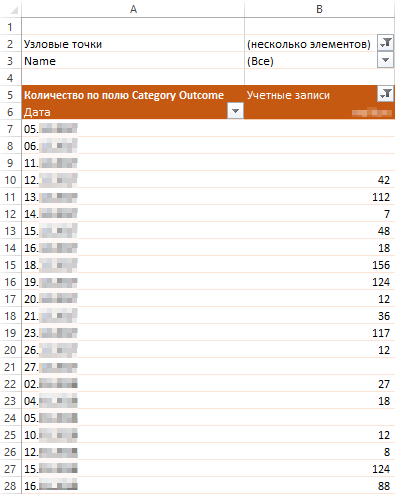

The number of DNS queries per day (vertical) from a specific IP address (horizontally)

Then you can highlight the cells in which any activity was observed, set filters on the domain names of the mining pool, remove obvious noises, add formatting to some other interesting domains, and as a result we will get a visual table from which you can select several patterns suggest how the attacker acted:

Pivot table with visual formatting

Most incidents begin with the same pattern:

Hypothesis No. 3. The attacker picked up a Ubuntu virtual machine with the same IP that the hypervisor had previously.

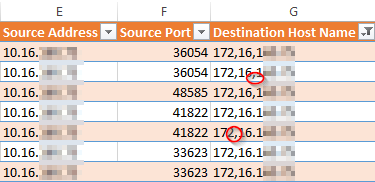

Right before the start of mining, more than half of the hosts turned to google [.] Com, and then immediately to download.minergate [.] Com. After that, each of these hosts two or three times requested a reverse DNS record for the same host from another network segment:

Reverse DNS queries about the nodal point

Hypothesis No. 4. After creating a virtual machine, the attacker opened a browser on it, logged into Google, found the miner’s download page, loaded it, and then went to the “nodal point” - a previously unknown server from which it downloaded the miner configuration file.

One confirmation of this hypothesis is the fact that some of the servers also requested domain names similar to IP addresses, but with an error: as if the attacker accidentally confused a comma and a period:

Malicious errors when accessing a nodal point

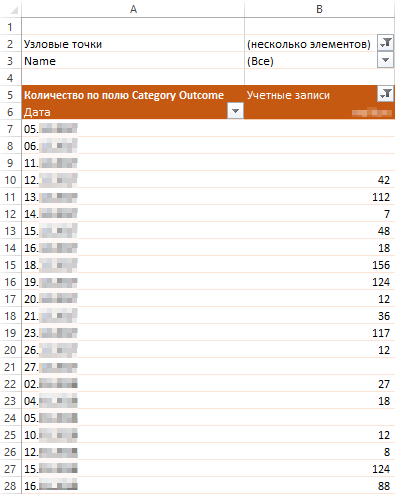

Fortunately, the domain controller closest to the nodal point was connected to the SIEM, which made it possible to find out who logged in with which account:

The number of attempts to authenticate all accounts at a nodal point. The only account is understandably overwritten.

Total:

So, at the time of the investigation, we had almost nothing. All discs are demagnetized, rubbed logs, the attacker learned that he discovered, and cleared the tracks. However, as you can see, the lack of information sources does not always mean that the matter is perilous. It is enough just to understand how the system works, and try to look at the input data in a non-trivial way - to play, twist the information, look for interpretation options. And then the investigation can be carried out successfully without expensive forensic tools and APT scanners, using literally just a standard office suite. And this, in our opinion, is the essence of forensics: it is not so important what tools you can use to investigate an information security incident, the main thing is a deep understanding of the principles of operation of the system and attention to detail.

You can have different attitudes to the cryptocurrency and tokens themselves, however, every security person has a negative attitude towards mining when it is performed unauthorized and on the equipment of the enterprise. We recorded and investigated many incidents where external violators spread miners into the load to the main malware module, hide it under the names of system processes (for example, C: \ Windows \ Sys \ taskmgr.exe), and sometimes there were cases when account network exploits, Psexec-ov and their analogues, and of course, malicious Javascript.

But, apart from the external violator, there is an internal violator. And more often he knows well what he is doing and how to hide the traces so as to go unpunished. One such case was asked to investigate.

')

Sometimes it is enough to look at the SIEM logs to understand who launched the miner: the following screenshot shows that the miner’s executable file was unpacked to the desktop of one of the server users:

Hypothesis 0. The employee did it deliberately, since the file is unpacked to the desktop. The likelihood that this made malware is minimal.

It is very easy to test such a hypothesis - just look at the antivirus log in the user's workplace. Surely the same rule previously worked on the archive, lying in the \ Downloads folder.

However, not always, looking at the journals in the SIEM, it turns out to establish who is the insider who violates the security policy of the enterprise. In such cases, incidents are transmitted to Solar JSOC CERT.

To business

As part of the provision of Solar JSOC services, there is a high-level entity — a monitoring scenario. It describes what incidents we are committed to identifying and how different monitoring lines should respond to them. Naturally, all customers are different, and each has its own set of scenarios, which are periodically reviewed and changed.

One afternoon, our colleagues connected a large client with a new scenario — the discovery of mining activity. 10 seconds after the inclusion of the rule set in the SIEM, we began to fix multiple DNS queries to the addresses of one of the mining pools.

An analyst on the part of Solar JSOC informed the client about “potentially undesirable activity”, and he blocked the calls on the firewall and proxy server. Worked out properly, and everything seems to be fine, and you can go on. But at the same time, the analyst also drew attention to the fact that mining was carried out from 32 different IP addresses, which, according to the documents, are hypervisors (and their capacities are considerable). We immediately reported this to the customer, who asked for a detailed investigation of the incident.

As soon as the case was transferred to JSOC CERT, we immediately began collecting digital evidence (hard drive copy, RAM, etc.), and then two unpleasant circumstances stood in the way of the investigation:

- The network segment in which mining activity was carried out was not connected to the SIEM (due to limited infrastructure coverage).

- The client did not have remote access to the hypervisors, because according to the documents they were written off for scrap 2 months ago .

At first, we proposed to disable the lockout of domain names of the mining pool in order to catch the attacker "on the bait," but after disabling the lock, activity did not resume. Apparently, the attacker realized that they learned about his activities, and turned off the miners.

Hypothesis number 1. An attacker could be someone of their own.

We are going to the data center to remove data on the spot. There we are shown empty racks and dumped demagnetized hard drives. Data center employees also worked out regularly: for information security, when dismounting hypervisors, the disks should be demagnetized, which was actually done 2 months ago - even documents with a seal confirmed this.

Hypothesis No. 2. Data center employees are involved in the incident.

As a result, we have an unpleasant situation when there are no target servers, the logs of their domain controller are erased (remember, this segment is not connected to SIEM), Internet access from the segment is not proxied, no netflow and no mention ... At such times, you should take a step back and remember what we have. And we only had DNS server logs ...

In cases when it is necessary to analyze a very large log, each incident response specialist uses “his own” utilities:

- Someone is using Event Log Explorer.

- Someone exports everything to Elastic / Kibana.

- Someone exports to csv and then sort-it and grep straight in the command line.

We use all of the above and even more, but in this case, the statistical analysis made in good old Excel, namely pivot tables, which convert a million of such records in a couple of clicks, was most obvious:

HPE ArcSight sample upload

in such a table:

The number of DNS queries per day (vertical) from a specific IP address (horizontally)

Then you can highlight the cells in which any activity was observed, set filters on the domain names of the mining pool, remove obvious noises, add formatting to some other interesting domains, and as a result we will get a visual table from which you can select several patterns suggest how the attacker acted:

Pivot table with visual formatting

Most incidents begin with the same pattern:

- First, the servers send DNS requests specific to the Windows system (requests to NTP servers and telemetry like telecommand.telemetry.microsoft [.] Com).

- Activity stops for a week, a day, and sometimes does not stop at all.

- Servers start sending requests that are specific to Ubuntu (ntp.ubuntu [.] Com, security.ubuntu [.] Com, us.archive.ubuntu [.] Com, and so on).

Hypothesis No. 3. The attacker picked up a Ubuntu virtual machine with the same IP that the hypervisor had previously.

Right before the start of mining, more than half of the hosts turned to google [.] Com, and then immediately to download.minergate [.] Com. After that, each of these hosts two or three times requested a reverse DNS record for the same host from another network segment:

Reverse DNS queries about the nodal point

Hypothesis No. 4. After creating a virtual machine, the attacker opened a browser on it, logged into Google, found the miner’s download page, loaded it, and then went to the “nodal point” - a previously unknown server from which it downloaded the miner configuration file.

One confirmation of this hypothesis is the fact that some of the servers also requested domain names similar to IP addresses, but with an error: as if the attacker accidentally confused a comma and a period:

Malicious errors when accessing a nodal point

Fortunately, the domain controller closest to the nodal point was connected to the SIEM, which made it possible to find out who logged in with which account:

The number of attempts to authenticate all accounts at a nodal point. The only account is understandably overwritten.

Total:

| No | Hypothesis | Check status |

| one. | An intruder could have been one of his own. | Confirmed |

| 2 | Data center employees are involved in the incident. | Disproved |

| 3 | The attacker picked up a Ubuntu virtual machine with the same IP that the hypervisor had previously. | Confirmed |

| four. | After creating the virtual machine, the attacker opened a browser on it, went to Google, found the miner's download page, downloaded it, and then went to the “nodal point” - a previously unknown server, from where it downloaded the miner's configuration file. | Confirmed |

Conclusion

So, at the time of the investigation, we had almost nothing. All discs are demagnetized, rubbed logs, the attacker learned that he discovered, and cleared the tracks. However, as you can see, the lack of information sources does not always mean that the matter is perilous. It is enough just to understand how the system works, and try to look at the input data in a non-trivial way - to play, twist the information, look for interpretation options. And then the investigation can be carried out successfully without expensive forensic tools and APT scanners, using literally just a standard office suite. And this, in our opinion, is the essence of forensics: it is not so important what tools you can use to investigate an information security incident, the main thing is a deep understanding of the principles of operation of the system and attention to detail.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/354392/

All Articles