Designing a Schemaless Uber Engineering data warehouse using MySQL

Designing Schemaless, Uber Engineering's Scalable Datastore Using MySQL

By jakob holdgaard thomsen

January 12, 2016

https://eng.uber.com/schemaless-part-one/

')

Designing a Schemaless Uber Engineering data warehouse using MySQL. This is the first part of the three parts of the Schemaless data warehouse series.

In Project Mezzanine, we described how we transferred Uber travel data from one Postgres instance to Schemaless — our high-performance and reliable data storage. This article describes its architecture, its role in the Uber infrastructure, and its design history.

Fight for a new database

In early 2014, we ran out of database resources due to the increase in the number of trips. Each new city, each new trip led us to the abyss, until one day we realized that the Uber infrastructure could not function by the end of the year - we simply could not store enough travel data using Postgres. Our task was to change the database technology in Uber, a task that took many months, and to which we attracted a large number of engineers from our offices around the world.

But wait, why build a scalable data warehouse when there are a lot of commercial and open source solutions? We had five key requirements for our new data warehouse:

Our data warehouse should have been able to grow capacity linearly by adding new servers, which was not enough in our Postgres installation. Adding new servers should both increase the available disk space and decrease the system response time.

We need high availability data storage at write . Previously, we implemented a simple buffer mechanism with Redis, so if the Postgres entry failed, we could try again later, since the trip was saved in Redis. During the time that the record was saved in Redis and not yet saved in Postgres, we lost functionality, such as billing. It's a shame, but at least we have not lost the trip! Over time, Uber has grown, and our solution based on Redis is not scalable. Schemaless data storage should support a mechanism similar to our solution with Redis, but provide read-your-write consistency.

We need a way to exchange messages with dependent components . In the system working at that time, we worked with dependent components sequentially within one process (for example, billing, analytics, etc.). It was an error-prone process: if a process step failed, we had to try again from the beginning, even if some of the process steps were successful. It did not scale, so we wanted to break the processes into isolated subordinate processes that would start in response to data changes. We already had an asynchronous messaging system based on Kafka 0.7. But we could not start it without data loss, so we would welcome a new system that had something similar, but could work without data loss.

We need secondary indexes . We departed from Postgres, however, the new data store should have maintained indexes at the Postgres level, which would also allow for efficient search of secondary indexes.

We need an absolutely reliable system , as it contains critical trip data. If at 3 am we are told that our data warehouse is not responding to requests and our business is destroyed, will we have operational information to quickly restore it?

In light of the above, we analyzed the advantages and potential limitations of some alternative widely used systems, such as Cassandra, Riak, MongoDB, etc. For purposes of illustration, a diagram showing the various combinations of capabilities of various systems is given below products):

| Linear extensibility | Write accessibility | Message exchange | Secondary indexes | Reliability | |

| Product 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | (✓) | ✗ |

| Product 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | (✓) | (✓) |

| Product 3 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | (✓) | ✗ |

While all three systems are linearly expandable by adding new servers, only two of them have high availability when writing. None of the solutions implement messaging out of the box, so we would have to implement it at the application level. All of them have indexes, but if you intend to index many different values, queries become slow, as they use the scatter-gather command to poll all nodes (shards).

Finally, our decision was ultimately determined by reliability, since we need to store trip-related data critical to the business. Some existing solutions can function reliably in theory. But do we have operational knowledge for the immediate realization of their most complete capabilities? After all, much depends not only on the technology that we use, but also on those people who were on our team.

It should be noted that, since we looked at these options more than two years ago and found that none of them are applicable when using a trip data repository, we successfully applied both Cassandra and Riak in other areas of our infrastructure, and we we use them in production to serve millions of users.

We are reliable at Schemaless

Since none of the above options met our requirements in accordance with the timeframes we had, we decided to create our own system, which was simplified to the maximum extent possible, using the scaling lessons received from others. The design was inspired by Friendfeed, and the emphasis was on the operating side, inspired by Pinteres.

We concluded that there is a need to design a key-value storage that allows you to save any JSON data without strict schema checking (hence the name schemaless). It was implemented on a MySQL server distributed on shards, with write buffering for fault tolerance, and publish-subscribe data exchange messaging, which is based on triggering calls. Finally, the Schemaless data warehouse supports global indexes.

Schemaless data model

Schemaless is an append-only sparse three-dimensional hash map, similar to Google's Bigtable. The smallest data object in Schemaless is called a cell and is immutable. After recording, it cannot be changed or deleted. The cell is a JSON (BLOB) object, which can be accessed using the row key, the column name, and the reference key, called the ref key. The row key is a UUID, the column name is a string, and the reference key is an integer.

You can represent a row key as the primary key in a relational database and the column name as a relational database column. However, Schemaless has no predefined or forced schema, and column names are not predefined for rows. In fact, the column names are fully defined by the application. Reference key ref key is used for versioning cells. Therefore, if the cell needs to be updated, you must write a new cell with a higher ref key (the last cell has the highest ref key). The ref key can also be used as an index in an array, but it is usually used for versioning. The way to use the ref key is determined by the application.

Typically, applications group related data into the same column, and all cells in each column have approximately the same schema on the application side. This grouping is a great way to combine data that changes together, and allows an application to quickly change the schema without idleness on the database side. Below is an example of this.

Example: Schemaless Trip Data Storage

Before we dive into how we model a trip to Schemaless, let's look at the anatomy of a trip to Uber. Trip data is generated at different times, for example: the end of a trip, payment for a trip, and these various pieces of information are received asynchronously. The diagram below is a simplified flow when different parts of a Uber trip occur:

The diagram shows a simplified version of our event flow. * denotes parts that are optional and may be present several times.

The trip is contacted by the driver who fulfills the order of the client, and has a time stamp for his start and end. This information represents the base (estimated) trip, and from this we calculate the cost of the trip (fare), which is the fare for the client. After the trip, we may have to adjust the tariff. We can add notes to the trip, considering feedback from the client or from the driver (marked with an asterisk in the diagram above). Or, perhaps, the client will have to make several attempts to pay for the trip with a payment card if one of his cards is blocked. The flow of events in Uber is a process driven by data. As data becomes available or added during a trip, a certain set of processes will be executed. Some information, such as assessing the quality of the service (considered part of the notes in the diagram above), may occur several days after the trip is completed.

So how do we compare the above travel model with Schemaless?

Trip data model

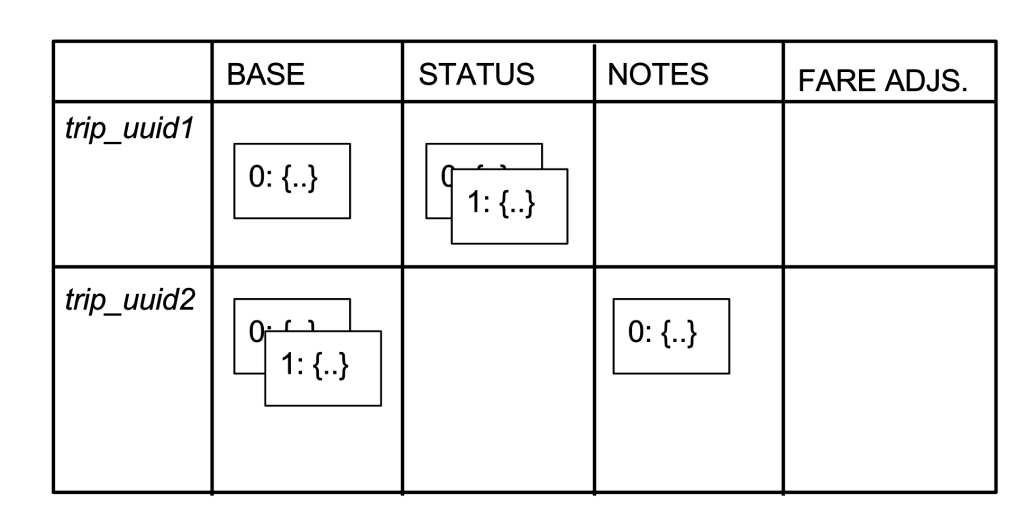

We will use italics to denote the UUID and upper case letters for the column names; the table below shows the data model for a simplified version of our trip store. We have two trips (UUIDs trip_uuid1 and trip_uuid2) and four columns (BASE, STATUS, NOTES and FARE ADJUSTMENT). Each cell is represented by a block with a number and a JSON object (abbreviated {...}). Blocks are shown overlaid to represent versioning.

trip_uuid1 has three cells: one in the BASE column, two in the STATUS column, and none in the FARE ADJUSTMENTs column. trip_uuid2 has two cells in the BASE column, one in the NOTES column, and also in the FARE ADJUSTMENTS column. For Schemaless, the columns are no different; therefore, the semantics of the columns is determined by the application, which in this case is a Mezzanine service.

In Mezzanine, the BASE cells contain basic trip information, such as the driver's UUID and travel time. The STATUS column contains the current status of the travel payment, in which we insert a new cell for each invoice attempt. (The attempt failed if the credit card did not have sufficient funds or the card was blocked). The NOTES column contains a cell if there are notes left by the driver or dispatcher. Finally, the FARE ADJUSTMENTs column contains cells if the fare for the trip has been adjusted.

We use this column structure to avoid race conditions and minimize the amount of data that needs to be recorded during the update. The BASE column is recorded when the journey is completed, and, as a rule, only once. The STATUS column is recorded when we try to pay for a trip that occurs after writing data in the BASE column and can occur several times if there was a failure to pay the bill. The NOTES column can also be written several times at some point after the BASE record, but it is completely separated from the STATUS column record. Similarly, the FARE ADJUSTMENTS column is recorded only if the fare is changed, for example, due to an inefficient route.

Pass-through triggers

A key feature of Schemaless are triggers that allow you to receive notifications of changes in a Schemaless instance. Because cells are immutable and new versions are added, each cell also represents a change or version, allowing values in the instance to be treated as a change log. For this instance, you can listen to these changes and run functions on them that are very similar to message buses, such as Kafka.

Schemaless triggers make Schemaless a reliable source of data, because, in addition to direct data access, the messaging system can use the trigger function to monitor and run any application code (the similar system is LinkedIn's DataBus), separating data creation and processing.

Among other use cases, Uber uses Schemaless triggers for invoicing when the BASE column is written to a Mezzanine instance. In the example above, when the BASE column for trip_uuid1 is written, our billing service, which runs in the BASE column, selects this cell and will try to pay for the trip through a payment card. The result of payment via a payment card, whether it is success or failure, is recorded in the Mezzanine in the STATUS column. Thus, the billing service is separated from the creation of a trip, and Schemaless acts as an asynchronous message bus.

Indexes for easy access

Finally, Schemaless supports indexes defined by fields in JSON objects. The index is queried through these predefined fields to find cells that match the parameters of the query. Querying these indexes is effective because requesting an index only requires accessing one shard to find a set of cells to return. In fact, queries can be further optimized, since Schemaless allows you to denormalize these cells by writing them directly to the index. The presence of denormalized data in the index means that only one shard is required to query the index to query the index and obtain information. In fact, we usually recommend Schemaless users to denormalize frequently requested data into indexes, in addition to getting a cell directly through a row key.

As an example for Mezzanine, we have an index that allows us to find trips given by the driver. We also denormalize the time of the trip creation and the city where the trip was made. This allows you to find all trips for the driver in the city for a certain period of time. Below we provide the definition of the driver_partner_index index in YAML format, which is part of the trip data store and defined above the BASE column (an example is annotated with comments using the standard #).

table: driver_partner_index # Name of the index. datastore: trips # Name of the associated datastore column_defs: – column_key: BASE # From which column to fetch from. fields: # The fields in the cell to denormalize – { field: driver_partner_uuid, type: UUID} – { field: city_uuid, type: UUID} – { field: trip_created_at, type: datetime} Using this index, we can find trips for a given driver_partner_uuid, filtered by city_uuid, and / or trip_created_at. In this example, we only use fields from the BASE column, but Schemaless supports the denormalization of data from several columns, which will contain several entries in the above column_def list.

As mentioned, Schemaless has effective indexes implemented by sharding indices based on a shard field. Therefore, the only requirement for a shard index is that one of the fields in the index is designated as a shard field (in the example above, this would be the driver_partner_uuid, since it is the first one specified). The shard field determines which shard should write or read the index. To do this, we need to determine the shard field when requesting an index. This means that at the time of the query, we need to request only one shard to retrieve the index entries. An important requirement for a shard field is that it must ensure a good distribution of data across shards. UUIDs are best suited, city identifiers are less preferred, and status fields (transfers) will do more harm than good.

With the exception of shard fields, Schemaless supports queries for equality, inequality, and a range of queries for filtering, and also supports selecting only subsets of the fields in the index and extracting specific or all columns for the key of the row pointed to by the index entries. At present, the shard field must be non-interleaved, which allows Schemaless to determine the shard on which the data is located one-by-one. But we are learning how to make it mutable without the cost of performance.

Our indices are consistent eventually (eventually consistent). Whenever we write data to a cell, we also update the index entries, but this does not happen in a single transaction. The cells and index entries usually do not belong to the same shard. Therefore, if we were to implement consistent indices, we would need to enter a two-phase commit when writing, which would entail significant overhead. As a result, with eventually consistent indexes, we avoid overhead, but Schemaless users may see outdated data in the indexes. Most of the time, the lag is well below 20 ms between cell changes and corresponding index changes.

Summary

We presented an overview of the data model, triggers and indexes, which are the key functions that define Schemaless - the main component of our trip data storage mechanism. In future posts, we will look at a few more features of Schemaless to illustrate how he became a good helper in the Uber infrastructure: more about the architecture, using MySQL as a shard and how we handle errors ensuring the reliability of the mobile application.

Part 2: Layout Architecture

Part 3: Using Triggers in Schemaless

It is an engineering project in Aarhus, Denmark. See our talk at Facebook's second annual conference on September 2015 for more info on Schemaless.

Photo Credits for Header: “anim1069” by NOAA Photo Library licensed under CC-BY 2.0. Image cropped for dimensions and color corrected.

Header Explanation: Since it has been built using MySQL, we introduce it.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/354050/

All Articles