7 principles for designing container-based applications

At the end of last year, Red Hat published a report describing the principles that containerized applications have to comply with, striving to become an integral part of the “cloud” world: “Following these principles will ensure application readiness for automation on cloud-based applications such as Kubernetes "- believe in Red Hat. And we, having studied this document, agree with their conclusions, and therefore we decided to share them with the Russian-speaking IT community.

Please note that this article is not a literal translation of the original document ( PDF ) prepared by Bilgin Ibryam - an architect from Red Hat, an active participant in several Apache projects and the author of the books Camel Design Patterns and Kubernetes Patterns - but presents its main points. in a rather free manner.

')

As a rule, with cloud-based (cloud native) applications, failures can be foreseen, and their operation and scaling is possible even when the underlying infrastructure has problems. To make this possible, platforms designed to run such applications impose certain obligations and restrictions on the applications launched in them. In short, the application is not enough just to put in a container and run - the possibility of its effective orchestration in platforms like Kubernetes requires additional efforts. What are they?

The ideas proposed here are inspired by various other works (for example,

The Twelve-Factor App ), covering many areas: from source code management to application scalability models. However, the scope of the principles discussed here is limited to the design of containerized applications based on microservices for cloud native platforms like Kubernetes.

In the description of all principles, the container image is used as the primary primitive, and the container orchestration platform is used as the target environment for its launch. Following these principles is intended to ensure that (prepared in accordance with them) containers will receive full support in most orchestration engines, i.e. will be serviced by the scheduler, scaled and monitored automatically. Principles are listed in random (rather than priority) order.

In many ways, SCP is similar to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) principle in SOLID , which means that each class must have one responsibility . The motivation behind the SRP - there must be only one reason that can lead to a class change.

The word “concern” (translated as “concern”, “concern”, “interest”, “task”) emphasizes that concern is a higher level of abstraction than responsibility , which better describes the range of container tasks (compared to the class). If the main motivation for SRP is the only reason for a change, then for SCP it is the ability to reuse the container image and its substitutability. If you create a container that is responsible for one task, and it solves it completely, the likelihood of reusing this image grows in other circumstances.

In general, the principle of SCP says that each container should solve a single problem and do it well. A classic from UNIX philosophy - DOTADIW comes to mind , “Do one thing and do it well” - comment . If microservice needs to be responsible for many problems, you can use patterns such as sidecar- and init-containers to combine multiple containers into a single deployable platform (under), where each container will continue to be engaged in the only task.

Containers - a unified way to pack and run applications that turns them into a “black box”. However, any container must provide application programming interfaces (APIs) for the environment in which it runs, making it possible to monitor the state and behavior of the container. This is a necessary condition for the possibility of automating container updates and maintaining its life cycle.

From a practical point of view, a containerized application should provide at least (at least!) An API for various checks of its state: liveness and readiness. It is even better if other ways are offered to monitor the state of the application - in particular, logging important events in STDERR and STDOUT for their subsequent aggregation with utilities like Fluentd and Logstash, integration with tools for assembling metrics: OpenTracing, Prometheus, etc.

The conclusion is: treat your application as a black box, but implement all the necessary APIs that help the platform monitor and manage the application as well as possible.

If HOP speaks of providing APIs from which the platform can “read”, then the LCP is the other side: your application should be able to learn about events from the platform. And even more: not only to learn about them, but also to react to them - hence the name of this principle (“conformance” is translated as “comply”, “agree”, “obey the rules”) .

The management platform may have many events that will help in managing the life cycle of the container, but some of them are more important than others. For example, for the process to shut down correctly, the application needs to receive a message with the appropriate signal (SIGTERM) in order to avoid an urgent termination of work through SIGKILL. There are other significant events - for example, PostStart and PreStop, which are necessary for the application to “warm up” at the beginning of its operation or, conversely, freeing resources at the end.

In containerized applications immutability is laid down: they are collected once, after which they are launched without changes in different environments. This implies the use of external tools for storing the data used in their work, as well as the creation / use of various configurations for different environments. Any change in a containerized application should result in building a new container image that will be used in all environments. The same principle, known as the immutable infrastructure, is used to manage the server infrastructure.

One of the main reasons for switching to containerized applications is that containers should be as short-lived as possible and ready to be replaced with another container at any time. There may be a lot of reasons to replace the container: status checking, backscaling (scale down) of an application, migration to another host, lack of resources ...

Therefore, containerized applications need to keep their state distributed and redundant. In addition, the application must quickly start and stop and even be ready for a sudden (and complete) hardware failure. Another useful practice in the implementation of this principle is the creation of small containers, since containers run automatically on different hosts, and their smaller size will speed up startup time (since they must first be physically copied to the host system).

The container should contain everything needed at the time of assembly, relying only on the presence of the Linux kernel (all additional libraries "appear" at the time of assembly). In addition to libraries, this also means the need to contain executable environments of programming languages, an application platform (if used), and any other dependencies for running a containerized application. The only exception here is configurations that will be different in different environments and should be provided during launch (for example,

Some applications consist of multiple containerized components. For example, a containerized web application may require a container with a database. This principle does not propose to merge containers: just the container with the database should have everything necessary for its operation, and the container with the web application for the operation of the web application (web server, etc.).

The S-CP principle considers containers from the perspective of build time and the resulting binary with its contents, but a container is not a one-dimensional black box lying on a disk. Other container “dimensions” appear when it is launched — these are “dimensions” of the consumption of memory, processor and other resources.

Any container must declare its resource requirements and pass this information to the platform, since its requests to the CPU, memory, network, disk affect how the platform performs scheduling, autoscaling, resource management, and provides a general SLA level for the container. In addition, it is important that the application fit into the resources allocated to it. In the event of a shortage of resources, the platform is less likely to stop or migrate such containers.

In addition to these principles, less fundamental, but often useful, container practices are also offered:

Links to additional resources on patterns and best practices on the topic:

Some of these principles - in particular, Image Immutability Principle (IIP), which we called as “One image to rule them all”, and Self-Containment Principle (S-CP) - were described in our report “ Best Practices CI / CD with Kubernetes and GitLab ” (click on the text and full video) .

Read also in our blog:

Please note that this article is not a literal translation of the original document ( PDF ) prepared by Bilgin Ibryam - an architect from Red Hat, an active participant in several Apache projects and the author of the books Camel Design Patterns and Kubernetes Patterns - but presents its main points. in a rather free manner.

')

As a rule, with cloud-based (cloud native) applications, failures can be foreseen, and their operation and scaling is possible even when the underlying infrastructure has problems. To make this possible, platforms designed to run such applications impose certain obligations and restrictions on the applications launched in them. In short, the application is not enough just to put in a container and run - the possibility of its effective orchestration in platforms like Kubernetes requires additional efforts. What are they?

Red Hat's approach to cloud native applications

The ideas proposed here are inspired by various other works (for example,

The Twelve-Factor App ), covering many areas: from source code management to application scalability models. However, the scope of the principles discussed here is limited to the design of containerized applications based on microservices for cloud native platforms like Kubernetes.

In the description of all principles, the container image is used as the primary primitive, and the container orchestration platform is used as the target environment for its launch. Following these principles is intended to ensure that (prepared in accordance with them) containers will receive full support in most orchestration engines, i.e. will be serviced by the scheduler, scaled and monitored automatically. Principles are listed in random (rather than priority) order.

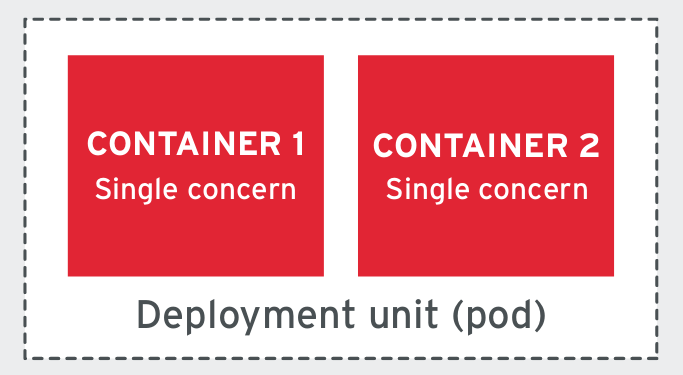

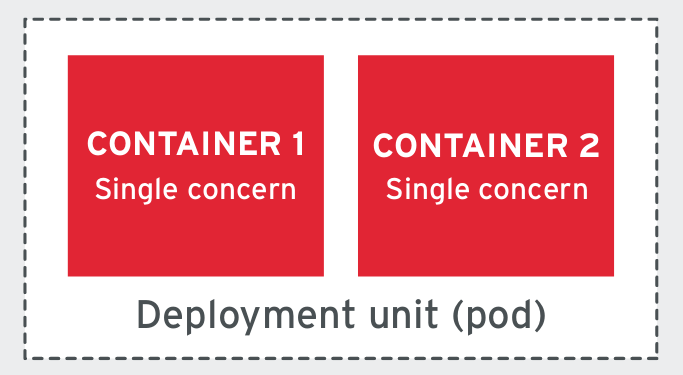

1. Single Concern Principle (SCP)

In many ways, SCP is similar to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) principle in SOLID , which means that each class must have one responsibility . The motivation behind the SRP - there must be only one reason that can lead to a class change.

The word “concern” (translated as “concern”, “concern”, “interest”, “task”) emphasizes that concern is a higher level of abstraction than responsibility , which better describes the range of container tasks (compared to the class). If the main motivation for SRP is the only reason for a change, then for SCP it is the ability to reuse the container image and its substitutability. If you create a container that is responsible for one task, and it solves it completely, the likelihood of reusing this image grows in other circumstances.

In general, the principle of SCP says that each container should solve a single problem and do it well. A classic from UNIX philosophy - DOTADIW comes to mind , “Do one thing and do it well” - comment . If microservice needs to be responsible for many problems, you can use patterns such as sidecar- and init-containers to combine multiple containers into a single deployable platform (under), where each container will continue to be engaged in the only task.

2. High Observability Principle (HOP)

Containers - a unified way to pack and run applications that turns them into a “black box”. However, any container must provide application programming interfaces (APIs) for the environment in which it runs, making it possible to monitor the state and behavior of the container. This is a necessary condition for the possibility of automating container updates and maintaining its life cycle.

From a practical point of view, a containerized application should provide at least (at least!) An API for various checks of its state: liveness and readiness. It is even better if other ways are offered to monitor the state of the application - in particular, logging important events in STDERR and STDOUT for their subsequent aggregation with utilities like Fluentd and Logstash, integration with tools for assembling metrics: OpenTracing, Prometheus, etc.

The conclusion is: treat your application as a black box, but implement all the necessary APIs that help the platform monitor and manage the application as well as possible.

3. Life-cycle Conformance Principle (LCP)

If HOP speaks of providing APIs from which the platform can “read”, then the LCP is the other side: your application should be able to learn about events from the platform. And even more: not only to learn about them, but also to react to them - hence the name of this principle (“conformance” is translated as “comply”, “agree”, “obey the rules”) .

The management platform may have many events that will help in managing the life cycle of the container, but some of them are more important than others. For example, for the process to shut down correctly, the application needs to receive a message with the appropriate signal (SIGTERM) in order to avoid an urgent termination of work through SIGKILL. There are other significant events - for example, PostStart and PreStop, which are necessary for the application to “warm up” at the beginning of its operation or, conversely, freeing resources at the end.

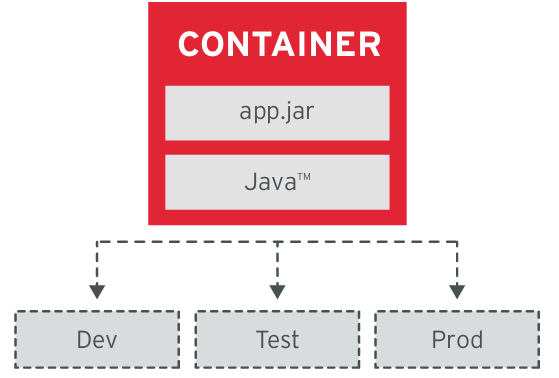

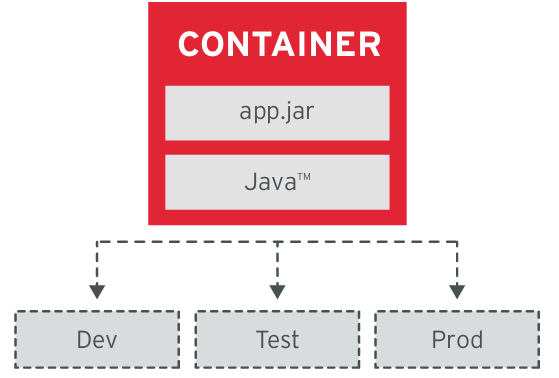

4. Image Immutability Principle (IIP)

In containerized applications immutability is laid down: they are collected once, after which they are launched without changes in different environments. This implies the use of external tools for storing the data used in their work, as well as the creation / use of various configurations for different environments. Any change in a containerized application should result in building a new container image that will be used in all environments. The same principle, known as the immutable infrastructure, is used to manage the server infrastructure.

5. Process Disposability Principle (PDP)

One of the main reasons for switching to containerized applications is that containers should be as short-lived as possible and ready to be replaced with another container at any time. There may be a lot of reasons to replace the container: status checking, backscaling (scale down) of an application, migration to another host, lack of resources ...

Therefore, containerized applications need to keep their state distributed and redundant. In addition, the application must quickly start and stop and even be ready for a sudden (and complete) hardware failure. Another useful practice in the implementation of this principle is the creation of small containers, since containers run automatically on different hosts, and their smaller size will speed up startup time (since they must first be physically copied to the host system).

6. Self-Containment Principle (S-CP)

The container should contain everything needed at the time of assembly, relying only on the presence of the Linux kernel (all additional libraries "appear" at the time of assembly). In addition to libraries, this also means the need to contain executable environments of programming languages, an application platform (if used), and any other dependencies for running a containerized application. The only exception here is configurations that will be different in different environments and should be provided during launch (for example,

ConfigMap in Kubernetes).

Some applications consist of multiple containerized components. For example, a containerized web application may require a container with a database. This principle does not propose to merge containers: just the container with the database should have everything necessary for its operation, and the container with the web application for the operation of the web application (web server, etc.).

7. Runtime Confinement Principle (RCP)

The S-CP principle considers containers from the perspective of build time and the resulting binary with its contents, but a container is not a one-dimensional black box lying on a disk. Other container “dimensions” appear when it is launched — these are “dimensions” of the consumption of memory, processor and other resources.

Any container must declare its resource requirements and pass this information to the platform, since its requests to the CPU, memory, network, disk affect how the platform performs scheduling, autoscaling, resource management, and provides a general SLA level for the container. In addition, it is important that the application fit into the resources allocated to it. In the event of a shortage of resources, the platform is less likely to stop or migrate such containers.

Other recommendations

In addition to these principles, less fundamental, but often useful, container practices are also offered:

- Aim for small looks. Delete temporary files and avoid installing unnecessary packages. This reduces not only the size of the container, but also the build time and the time it takes to transfer data over the network when copying images.

- Support any UID. Avoid using the sudo command or a specific user / UID requirement to start the container.

- Mark important ports. Their designation using the

EXPOSEcommand simplifies the use of images for both people and software. - Use volumes for persistent data (such that must be saved after container destruction).

- Identify metadata in images - using tags, labels, annotations. This simplifies their further use by developers.

- Synchronize the host and image. Some containerized applications may require synchronization with the host for certain attributes (for example, time and machine ID).

Links to additional resources on patterns and best practices on the topic:

- Container Patterns (Matthias Luebken) ;

- Best practices for writing Dockerfiles (Docker) ;

- Container Best Practices (Project Atomic) ;

- OpenShift Enterprise 3.0 Creating Images Guidelines (Red Hat) ;

- Design patterns for container-based distributed systems (Brendan Burns, David Oppenheimer) ;

- Kubernetes Patterns (Bilgin Ibryam, Roland Huß) ;

- The Twelve-Factor App (Adam Wiggins) .

PS from translator

Some of these principles - in particular, Image Immutability Principle (IIP), which we called as “One image to rule them all”, and Self-Containment Principle (S-CP) - were described in our report “ Best Practices CI / CD with Kubernetes and GitLab ” (click on the text and full video) .

Read also in our blog:

- “The Death of Microservice Madness in 2018 ”;

- " CNCF Guide to Open Source Solutions (and more) for cloud native ";

- “ How many developers think Continuous Integration is not needed? ";

- " Our experience with Kubernetes in small projects " (video of the report, which includes an introduction to the technical device Kubernetes).

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/353272/

All Articles