Improve performance review

I talked about how many times I did inside the company in Avito performance reviews , and this spring also at two conferences — TeamLeadConf and CodeFest . We are actively investing in finalizing the process, conducting many experiments and collecting a lot of useful data, therefore each new performance consistently includes some kind of new content. The purpose of this article is not to give you a ready-made boxed solution, but to share all the practices and insights that we found on our way.

TL; DR

The article was quite voluminous. To attract attention, here is a list of what I'm talking about.

- What are the steps involved in the Avito performance review process, how to write a good self review, and why break respondents into different roles.

- How to deal with issues of anonymity and gradually lead the team to a culture of open feedback.

- What data and analytics we pulled out of 10,000 estimates collected.

- How to automatically identify those carelessly related to the performance review, systematically underestimates or overestimates.

- What is the normalization and adjustment of estimates and how it works.

- What are the standard anti-patterns in feedback, and how they can be identified.

- What set of templates to use for a quick start in your company and how to approach the issue of automating the process.

Introduction

The question of how to evaluate the employee’s contribution to the company’s results is concerned, perhaps, with almost all managers. Having a clear picture of this issue is really very cool - we get an honest tool for determining remuneration for employees, comparing teams with each other and all that. And in the first approximation, the task does not seem too complicated.

We at Avito for goal-setting use the OKR methodology . This is something like MBO on steroids. We build a tree of goals for the entire organization from a strategic level to a specific team. Goals determine business or customer value, and key results establish measurable and unambiguous signs of achieving goals. There are still different principles included in the kit: ambitious goals, otvyazka from material motivation, publicity, measurability - but not the essence, my story is not about that, although I strongly recommend strongly reading about OKR.

In theory, everything sounds cool: the goal tree is broken down to a specific specialist, we see its results for the quarter and use them to evaluate its contribution. But in reality, of course, this is not how it works. When the whole team applies a hand to achieving the goal, it is very difficult to separate the personal contribution of each particular specialist and evaluate it in something concrete, as required by the methodology. Well, after all, it is true - if the feature fired and brought benefit, you can’t say that Petit’s merit is twice as much as Vasya. Not in commits, we will consider this.

And this is only one side of the problem. We must not forget that most of the time an employee’s activity is not only in his team. He can make reports, help other colleagues with their tasks, promote some common engineering approaches. And this, too, can be both beneficial and harmful. And one moment. To achieve their goals can be very different. Someone knows how to negotiate, notify all interested, take into account the interests of other people. Well, someone else can go over their heads, interfere with other teams and chase only their indicators.

We get the standard situation. In theory, the assessment of a person by the results is beautiful, but in practice, when approaching the head does not work. I came across this when I came to Avito. We had a lot of teams, everyone worked on OKR, but we didn’t know how to assess the quality and effectiveness of the work of specific people. After studying the experience of other companies, we came to the need to implement a performance review process, which in its first approximation very much resembled the models used in Google and Badoo. You can read about Google in the great book by Laszlo Boca “Jobs a Taxon”, and about Badoo you can read an article or listen to a report by Alexei Rybak. But, which is very important, we did not stand still. Taking the finished model as a basis, we gradually, conducting a series of experiments and collecting data, began to improve it.

How performance review works

Now we do a performance review once a quarter, and on average we have about two to three weeks from the beginning to the end.

The process consists of five basic steps:

- preparing self review,

- definition of respondents

- starting the process

- assessment,

- summarizing.

Self review

First of all, the evaluated employee prepares self review. This is an important point of reflection, when you sit down and remember what you have been doing for the past few months. I can immediately say that the process is long and painful - it takes at least an hour or two. It is convenient to take a blanket, pour cocoa, turn off notifications in the messenger, and prepare for the appearance of a slight plaque of depression - I myself know that the results can be quite frustrating.

In order to make it easier for respondents to work with your stream of thoughts, I recommend breaking self-review into four sections.

First section Roles and expectations. Includes a description of the expectations of your positions and roles. In our case, these are documents in Confluence with a detailed description of the tasks and qualities expected from the employee. There may be information about functional expectations from engineers, a description of the role of a mentor, a speaker, a participant in an educational program, a leader unit, or those. leader unit - in short, any position and role in which you act. These data are designed to help respondents write correct reviews and understand what the company expects of you.

Second section What they were doing. Brief results of the last evaluation period. This is the key section in which you list all the projects and activities you were engaged in. These could be the goals of your team that you actually influenced, the projects you worked on, the details of your basic functional responsibilities. It is also worth mentioning about your plans for growth and development and to emphasize what you did to achieve what you want. Any additional activities such as speaking at meetings or participating in hackathons are also added here. Try not to pour water, but talk only about the facts. If someone from the respondents does not have enough information to assess, he can easily get it from you. Let people appreciate facts, not beautiful words.

Third section What was good. Here you list the facts that you consider your main achievements and successes. Mainly focus on work achievements - successfully launched projects, established relationships with someone, successfully released trained beginners. Again, do not be wordy and try to keep the focus on the main point.

The fourth section. What was bad. List your major failures as openly as you can, what you yourself are unhappy with and what you would like to correct and improve in the future. This can include both the failures of specific goals set for you or the team, and your personal mistakes. It’s not worth hitting on self-criticism either, nobody has canceled the focus.

Let's look at some good and bad excerpts from self review. Part was invented, part - taken from real examples.

"I drove the development of a mobile design platform, which is almost completed and ready for deployment into the application."

This is a good example. Evaluated explicitly indicates what project he was engaged in and what state he was brought to.

"Too little time spent mentoring, which is why entering Ivanov into the company is much worse than planned."

This is also an example of a good filling. A clearly marked error - little time was spent on mentoring, and the result was underlined - entering a new employee into the company went badly.

“I don’t even know ... I just worked, I did tasks.”

Now a bad example - here, in principle, everything is clear and without explanation - no specifics, no desire to analyze their activities and understand whether it was good or not.

"Mowed a couple of times, but everything seems to be normal."

And one more example - the assessed hints that it fully complies with its expectations, but in order not to seem completely perfect, the phrase “squinting a couple of times” gains the confidence of the respondents. Here is the same thing as in the previous example - the reluctance to describe specific facts makes life very difficult for those who will evaluate this person.

Definition of respondents

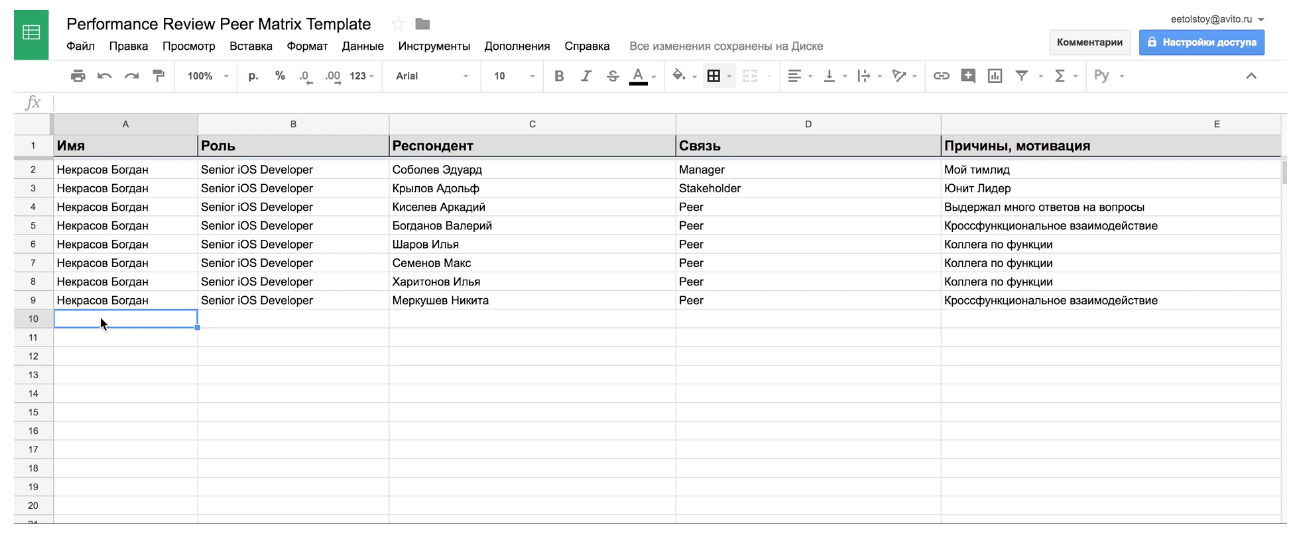

At this stage, the evaluated chooses its respondents. We divide them into four groups. Consider them on the example of the abstract developer mobile applications Bones.

1. Manager

The most important respondent is the immediate supervisor of the employee. In the case of Kostya, this is Ivan, the head of the mobile application development team. Kostya and Ivan work in different teams, but this does not prevent Vanya from participating in the assessment.

2. Stakeholders

The next group of respondents is the stakeholders. In the case of Kostya, these are two people — his product manager, Pavel, and the head of the function, Yegor. Pasha constantly interacts with Kostya as part of his work on the team’s goals, and Egor periodically connects Kostya to the preparation of meetings and the work on open-source projects. This group may include products, leaders of other units - in short, customers of your services.

3. Peers

Usually the largest group is peers. Kostya has included all his teammates with whom he is working on his tasks here - these are several iOS developers, android and backend developers, designers and testers. A couple of times in the last few months Kostya intersected with a common task with the guys from the platform team, but decided not to include them here, because they had relatively little time to work together. Kostya also did not include those guys with whom he just goes to dinner and bars - he understands that their assessment of his productivity has nothing to do with his working successes. Kostya is well done, be like Kostya.

4. Subordinates

And the last group of respondents are subordinates. Kostya was lucky, he had no subordinates. Even informal subordinates should be added here. For example, you are the lead developer, and part of the time mentor Junior.

Running process

The third stage lies entirely on the shoulders of the head - he reads all the data received from the employee, prepares reviews and sends them to the participants.

First of all, the manager looks at the results of self review. Looks carefully, notices all the flaws, says what information should be added, and what - to remove, gives additional advice on the form. All the comments of the head must be taken into account and corrected.

A similar procedure takes place with a list of respondents. The manager looks at it, assesses the relevance of the participants, can remove or add someone. In general terms, you should be able to explain to the manager why they added this or that person, and how they worked with him in the last few months.

Then the manager starts a review in our performance review tool. All participants receive notifications on slack and the evaluation period begins.

Evaluation

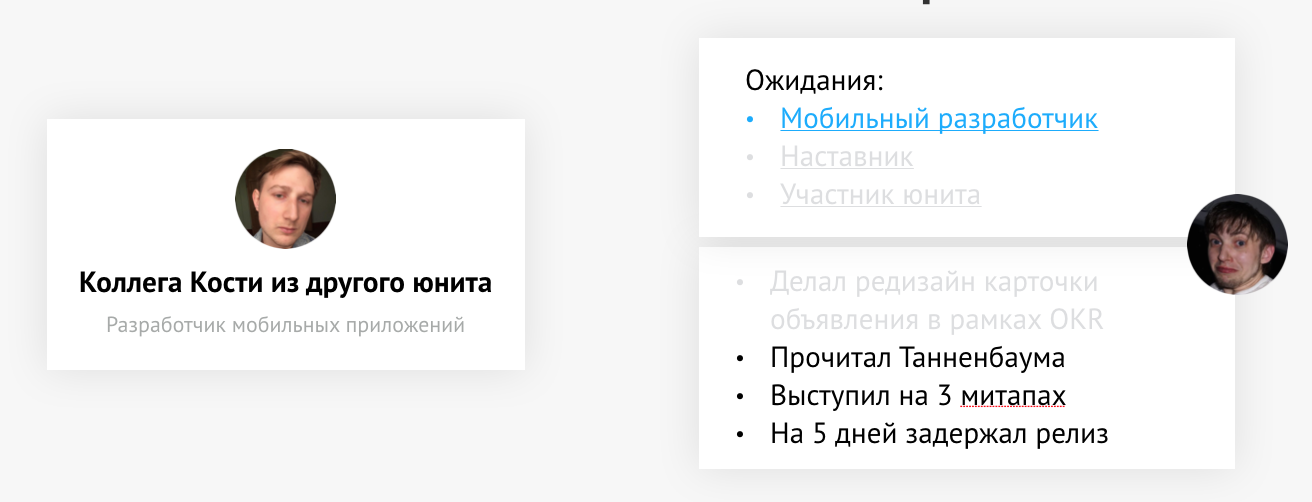

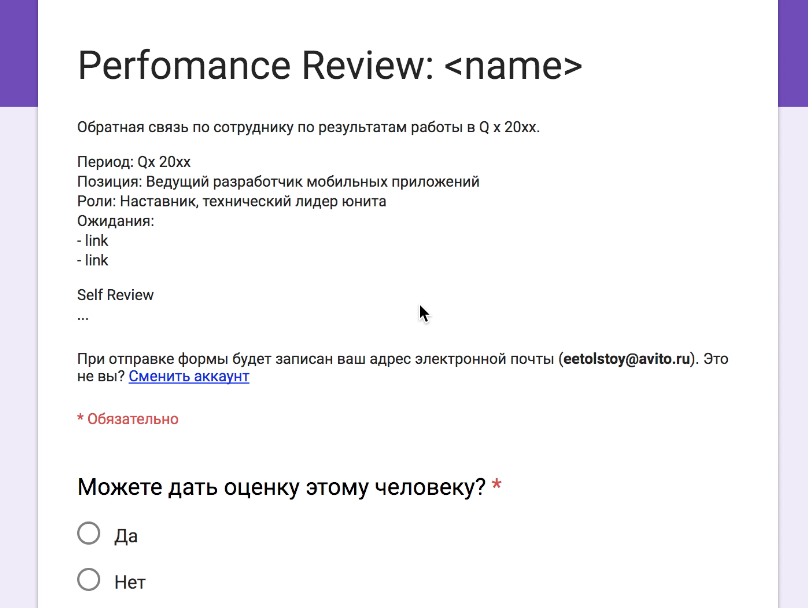

Now it's time to switch the mindset and go to the role of respondents. Let's look at how Kostya assesses his colleague. He reads self-review, looks at the list of attached expectations and notes relevant for himself - those aspects of his work with which he dealt and can adequately evaluate.

We have such a grading assessment.

- (1) Significantly below expectations

- (2) Below expectations

- (3) Meet Expectations

- (4) Above Expectations

- (5) Significantly higher than expected.

- (0) Difficult to give an assessment

In the current case, Kostya’s activity as a representative of the mobile development function and all of his activities, besides working in his team. The respondent works in another team and cannot evaluate this work by Bones.

Rating: “Below expectations”

Comments on the assessment:

“Instead of asking for help, he buried himself in the problem for weeks. In addition, I have not yet begun to navigate the company. ”

')

What to start doing:

- learn more about platform development,

- establish communication with your colleagues,

- overcome the fear of asking for advice.

What to stop doing:

- play PS at night

- be silent on common sync-apah, afraid to express your point of view,

- try to solve all the problems yourself.

In the end, he puts Kostya assessment "below expectations". Judging by the comment, a colleague believes that the main problem for Kostya as a developer is the unwillingness to turn to his comrades for help in solving problems. The second problem is the inability to navigate the company, which is also a mismatch with expectations.

Included are a few development tips - more actively explore platform development, and not dig into Tannenbaum, establish communication with colleagues and overcome the fear of asking for advice. The last two points correlate directly with his commentary. And in the section “what to stop doing” the respondent touches another interesting point - silence at general meetings, unwillingness to actively express and promote his point of view. Feedback looks constructive and useful - Kostya’s manager can calmly start working with her and help him correct the situation.

Next in line is the second respondent, Pavel. Pavel, as I mentioned, is the product manager of the team Kostya works for. Kostya's assessment of Paul is actually based on completely different expectations and facts of his activity. This is absolutely correct, because the type of their interaction was completely different.

Rating: “Above Expectations”

Comments on the assessment:

“Kostya is the best. He helped build the planning processes in the unit and offered a bunch of great ideas to achieve our OKRs. If it were not for Kostya, our unit would not have managed this quarter. ”

What to start doing:

- dive into the problems of users, participate in their identification and analysis,

- Involve other colleagues in cross-functional activities.

What to stop doing:

- work on weekends - at a pace you can burn out in six months,

- drink energy,

- soar vape in conversations.

Paul's assessment is also very different - “above expectations”, an excellent result. The comment is written in a completely different key, Pavel is very pleased with Kostya and gives a bunch of examples of his benefits for the team. Note that there is not a word about the shortcomings with which the previous respondent had dealt. This is just the other side of man.

Paul’s development tips are also different; they are about growth in the direction of product analysis and cross-functional interaction. And the “what to stop doing” section is pretty standard - out of all the reviews I saw, every second person is asked to take a vacation, stop working at night or on a weekend. The moral is - you need to try to connect to the assessment of very different people - this will help you collect criticism about different aspects of your activity.

Summarizing

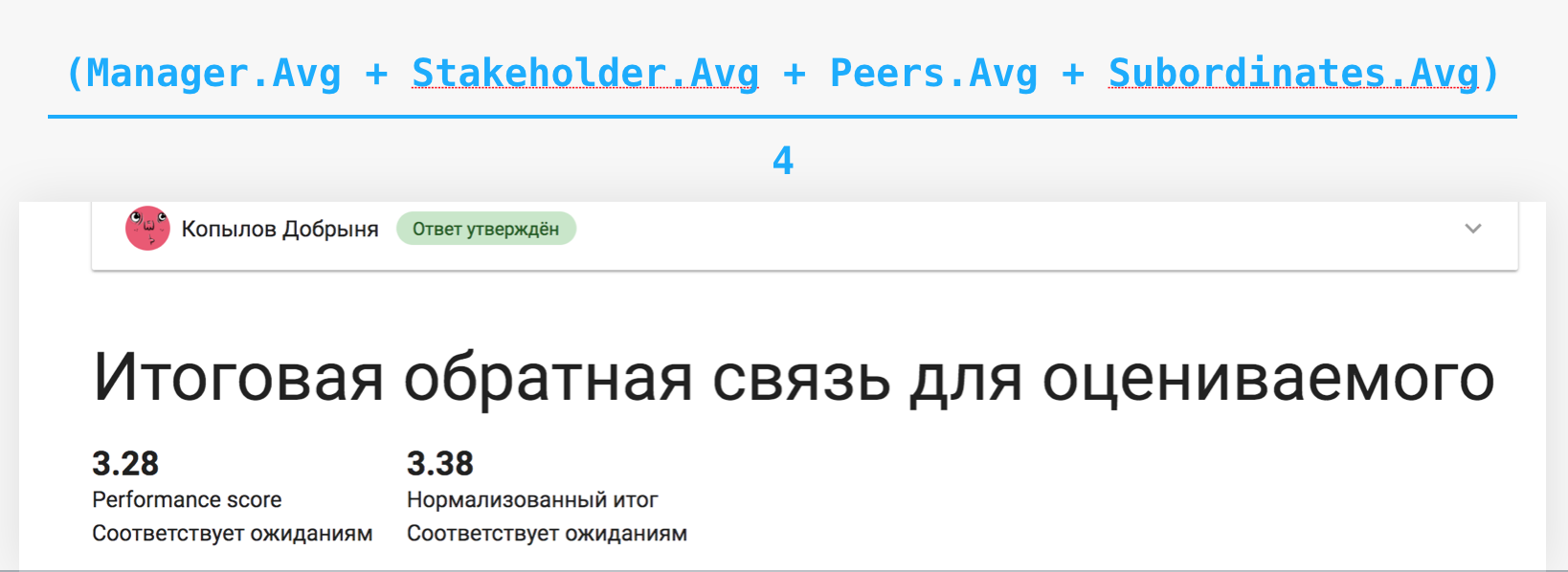

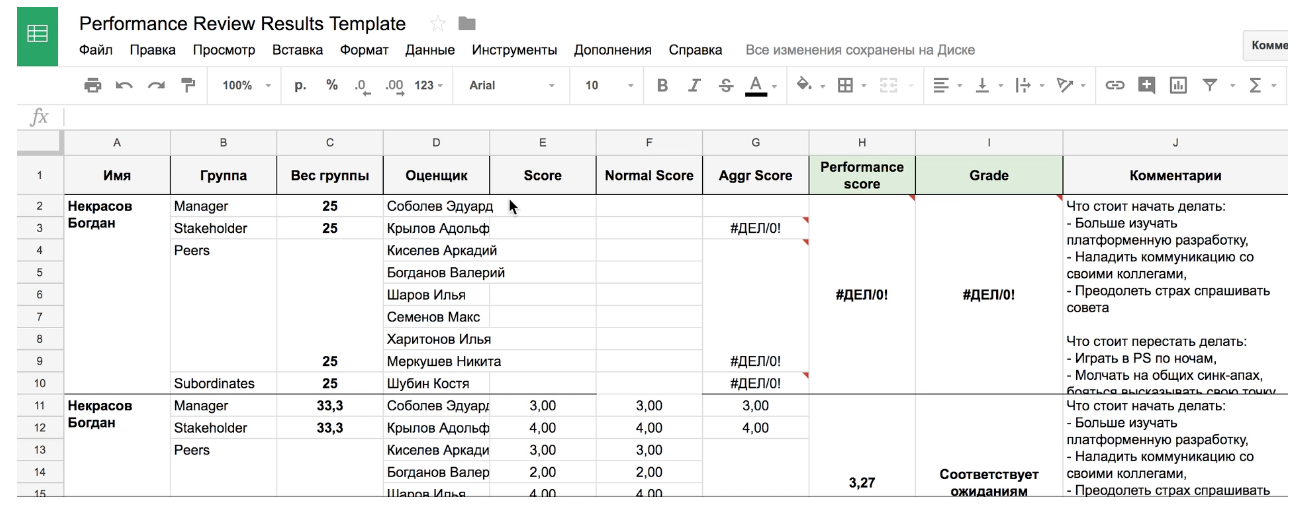

The last stage again falls entirely on the shoulders of the manager. First of all, it aggregates all received feedback, while examining it for the presence of anomalies. If the manager encounters an unfair assessment, he either calibrates it himself or contacts the respondent for additional clarifications. Then, according to a cunning formula, the final result is calculated.

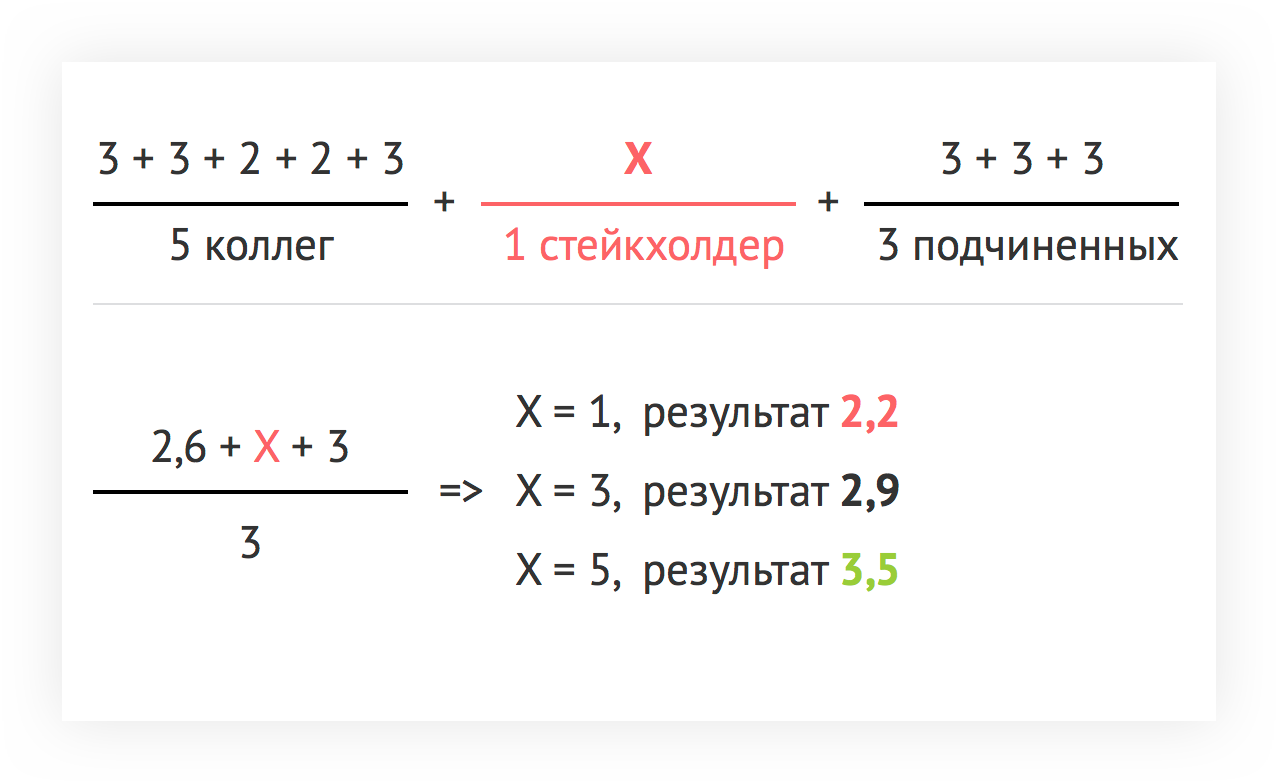

As I already told, all respondents are divided into four groups: manager, stakeholders, peers and subordinates. For each group, the average estimate is calculated, then the average for all groups, taking into account the equilibrium distribution. And the resulting number is converted into one of the already familiar categories - below expectations, in line with expectations ... The resulting estimate and reaches the employee.

After summarizing the performance review, the manager holds a meeting with his employee, where he reports to him the final assessment and structured feedback. This feedback is discussed with the employee. As a result of this meeting, an action plan is usually drawn up and the manager continues to work with the employee during the quarter, solving the problems found. In addition, the review score for the manager and the employee becomes a transparent tool for growth in the company.

Having dealt with the way the performance review process works for us now, let's move on to the details that are the essence.

Performance review practices

Anonymity

Even before the full launch of performance review on all employees, we conducted a series of experiments on limited groups to obtain the first data sets that can be used to further develop the process. One of these experiments was about anonymity.

In general, anonymity in performance review is a rather complicated topic. Offhand, there are several different ways to implement.

The first is the simplest: everyone sees everything. Each employee has full feedback from all his peers. He knows who and what he wrote, what grade he gave. From the pros - the effect of a broken phone disappears. The evaluated person can always understand what the review was related to, based on the identity of the person who left it. And if you do not understand, then you can always come up and find out the details personally. Of the minuses - with an insufficient level of maturity of the collective, this can provoke serious conflicts and offenses. In addition, people can begin to be silent about the problems, preferring to get by with a "three" (corresponds to expectations) and an empty comment.

The second option - impersonal feedback, in which there is no clear indication of the author. Before you open the results to the employee, all the answers are reviewed by the manager, mixed, can be further cleared. With this approach, we solve the problem posed earlier. If the author of the review is unknown, then there is nobody to be offended. But another serious problem comes out - it is very difficult to give an impersonal, but still constructive and useful feedback.

Well, quite a hardcore version. The manager independently processes all the reviews and reduces it to the set of recommendations of the “what was good”, “what needs to be improved” format. There are no particular advantages - in fact, in any of these approaches, the manager should do this exercise, even if only for himself. And the main disadvantage is that the context is lost. The manager may miss something important, personal, that only the person being evaluated can understand, or misinterpret some facts.

We conducted experiments with all formats, and revealed the pros and cons that I listed. As a result, we decided to go the next way - we set a goal for ourselves to go to a fully open feedback, but we decided to go for it gradually. In the first round, managers always gave impersonal feedback. Some reviews were difficult to deanonymize, but in general terms it was possible to maintain the appearance of anonymity. In parallel with those respondents who wrote frank trash in the comments, educational work was carried out - we dealt with complex cases, determined acceptable norms of behavior.

In the next round, a review by decision of the manager showed not impersonal feedback to some employees, but most of them were still anonymous. The results performed well, no conflicts were noticed, but people began to discuss feedback with respondents, ask questions and there was a much more understanding of the reasons for the presence of some reviews.

With each subsequent round, we gradually opened up more reviews, teaching our employees to the culture of open feedback. As a result, now we have come to the state that everyone sees everything with rare exceptions. For example, only a formed team, or some other special cases. But in general, the decision on the anonymity of the results always remains on the manager.

Work with data

We began to collect adequate data from the moment of the first large-scale review — this is the second quarter of 2017. During this time, we collected more than ten thousand ratings from 1000 respondents.

We did not initially put a hard limit on the number of respondents in the review, denoting an approximate threshold of 10 people. In the end, everything came to this number itself. The reasons are clear - this is, in fact, a two-pizza-size team, plus several respondents outside the team. “Tails” here are either managers with many projects and communications on them, or engineers from very small teams.

And this is a histogram of the number of assessments that people put in one review. It is seen that for most it ranges from 1 to 11 ratings. Taking into account the average duration of a review of about 25 minutes, it turns out that it is necessary to kill no more than 6 hours per quarter for rating the colleagues, and taking into account the focus factor of 0.5. This is quite a bit, so it’s quite easy for people.

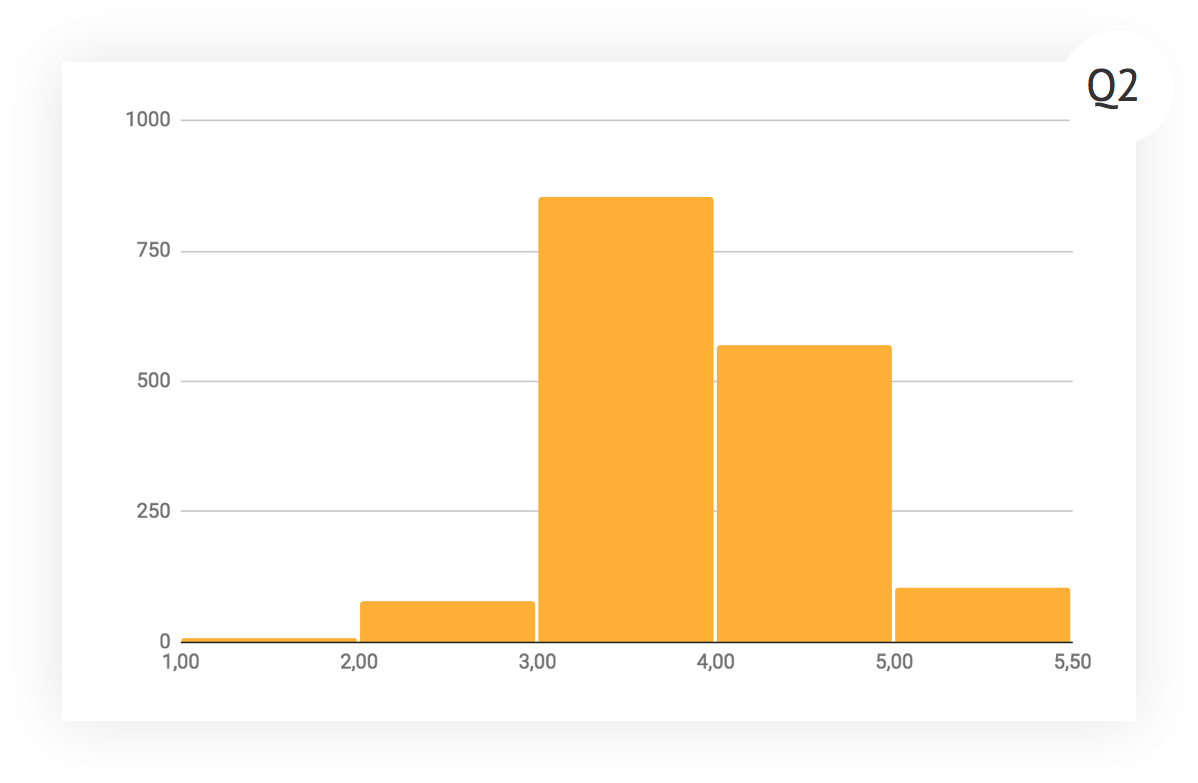

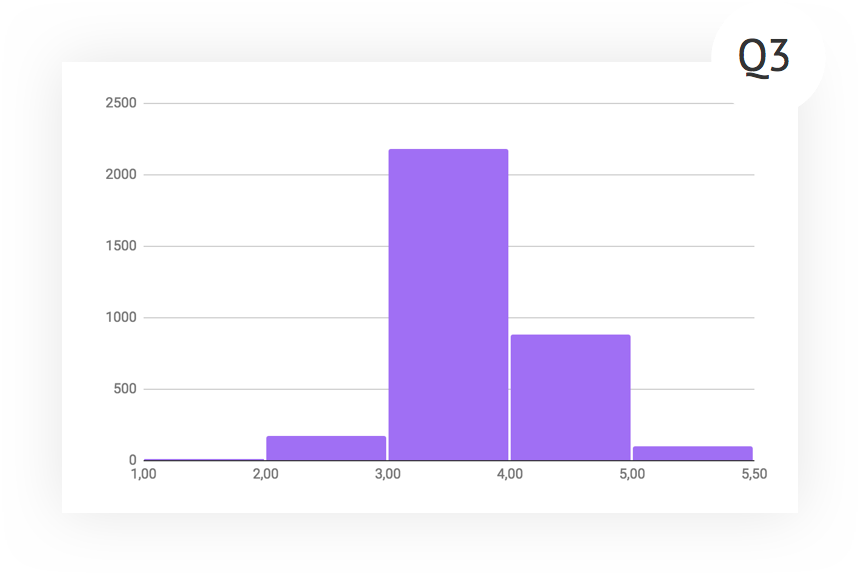

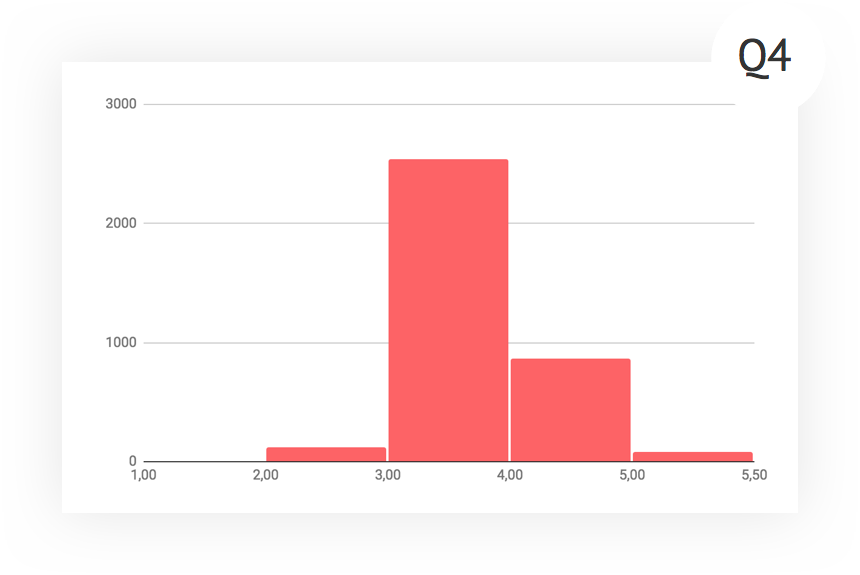

Now let's explore how the distribution of ratings changed over time. This is the histogram for the first quarter of the review. There is a strong bias in the direction of good, the number of fours (“above expectations”) is approaching triples (“corresponds to expectations”). There were two hypotheses - either we have many undervalued superprofessionals, or we are not able to think critically and to approach the assessment correctly.

By the next quarter, we worked in both directions. Those who excelled were pumped and transferred to new positions, and additional work was carried out with those who stood out with a large number of positive and poorly substantiated assessments. In addition, this time the managers paid more attention to sending a review for revision.

Interestingly, in the last quarter, the schedule almost did not change. The average score decreased literally quite a bit, the shape of the histogram is also unchanged. In principle, we arrived at a certain period of stability, and, conducting further experiments, we can evaluate their influence by studying the deviations from the current form of the graph.

There were a number of interesting experiments. For example, about the study of the presence of intergroup conflicts or hostility. I compared the average marks that all respondents give to members of their team with the marks they give to members of other teams. As a result: there are practically no serious discrepancies, on average, the scores of both groups are approximately equal, at the ends of the intervals there are discrepancies of a maximum of 0.5 point. The hypothesis that people tend to overestimate their team's grades and underestimate others has not been confirmed.

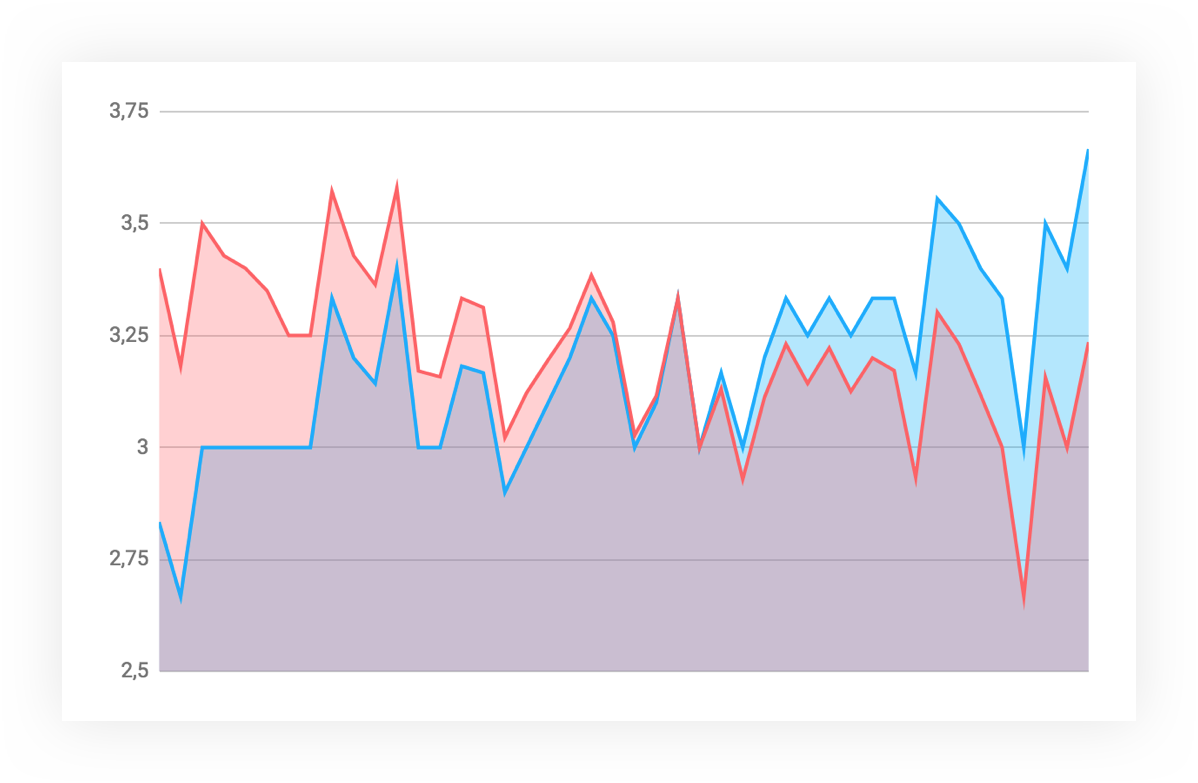

Another hypothesis that I tested is the influence of the role to which the respondent belongs on his assessment. And here everything was confirmed. Most of all, the difference is visible at the start of the process, when the evaluations of managers and subordinates differed by half a point. By the current moment, the differences have smoothed out, but managers continue to be the toughest reviewers - in principle, they are critical in their status.

These results strongly correlate with the distribution of estimates in the first quarter. It can be seen that the managers initially had a much clearer understanding of how to approach the evaluation. Due to the fact that we poorly brought the whole methodology to the rest of the staff, and it turned out to be a bias towards “above expectations”.

Evaluation Profiles

According to the results of each quarter, we distinguish three bright groups of respondents that correspond to one of the three evaluation profiles - kindness, fairness or hard work.

Let's go through each profile and start with kindness. In this group, people fall under the following conditions: gave more than 4 ratings, the average score is above 4.1, there are no units and two among the ratings. Getting into this profile usually has several reasons. For example, a person is really very kind and it is hard for him to write criticism. Or the respondent has low expectations, so even work at an average level seems to them to be over-fulfilled. And, of course, it may indeed be the case that the whole circle of those evaluated refers to steep performers - but this is rather an exception to the rule.

Justice is the same story, but vice versa. We are looking for people who put less than 2.7, did not put the ratings above the average and made more than four reviews. At once I will say that there are significantly fewer such, at least in our case. Well and, by the way, getting into this group can be a marker of what a person is uncomfortable working in his current team.

The last profile - hard work - this is the worst case. Here we include people who have spent relatively many reviews, the average rating is three, and the variance is zero. Well, as an additional filter, we look at the size of the comments left and focus on those who write much less than the average volume. This set of characteristics clearly indicates people who do not bother thinking about someone else's review, but put down the average ratings, insert a simple reply and move on.

In addition to the evaluation profiles, we look at a number of other anomalies, among which there are both fairly obvious things - who write a lot and few comments, for example, and more unusual ones.

One example is to examine the results on the emergence of strategies of a degenerate group. According to our evaluation formula, all groups of appraisers have equal weight. Within the group we consider the average estimate. Thus, the smaller the number of people in a group, the greater the share of the evaluation of its participant. Here is an example - there are three groups. A person is evaluated by five colleagues, three subordinates and one stakeholder. . , .

, . , . , , .

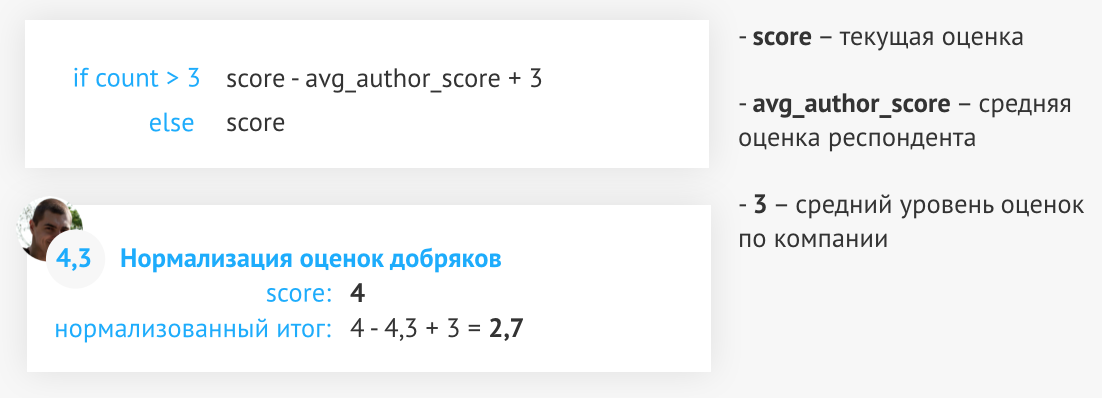

, , , . , , , 3 (« »).

, . , , — 4,3. - , . , 2.7.

. , , , . .

. — 2,4. , . — 4, .

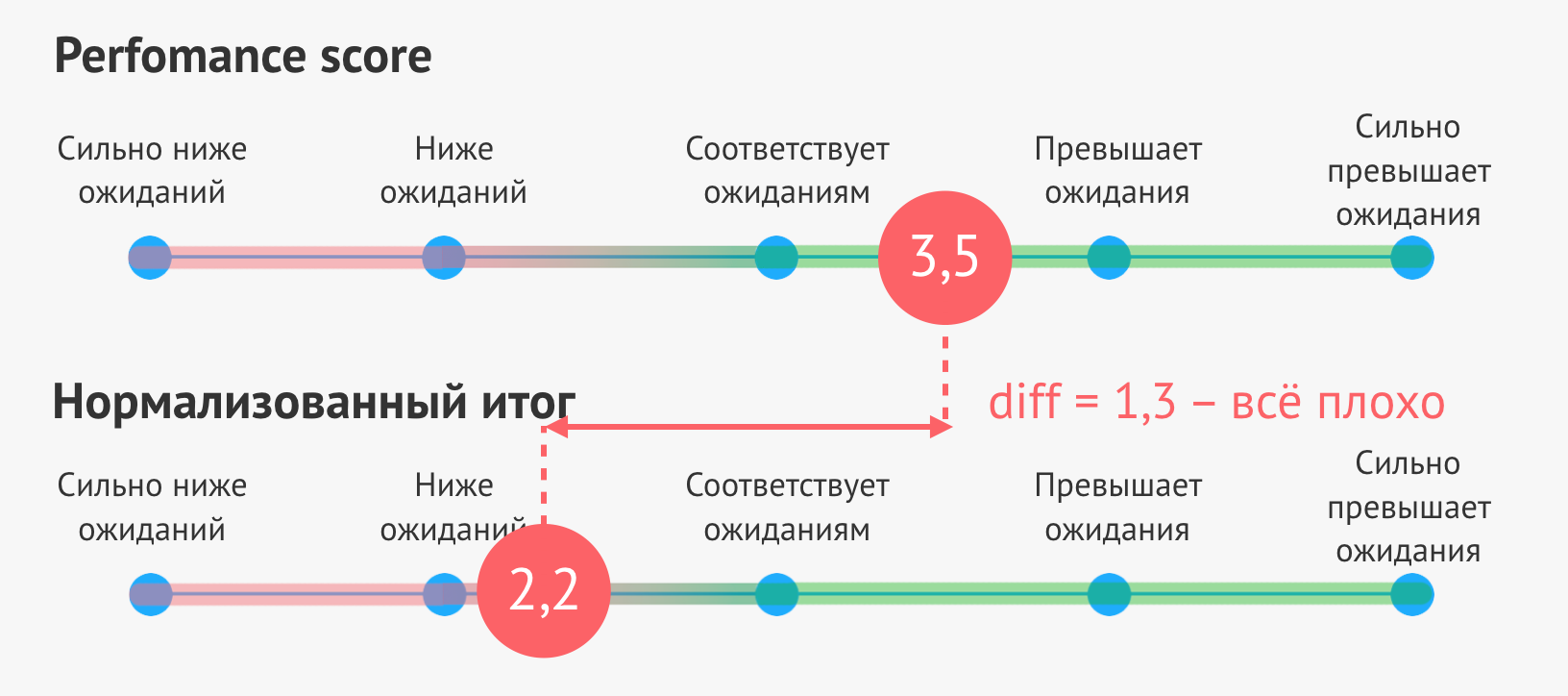

— performance score . — , . .

.

- performance score , .

- performance score (, 0.5), , , . , performance score .

. , , . , , . , , . . , , . — , , . .

, « ». . , , , . , . , . , , . — , 3.977 , 62, 80% , .

, , — .

.

, .

: « ».

: « . — ».

— . , - , — .

— , . , , . , , , .

.

, .

: « ».

: « 2014 , , . , ».

. . Performance review — , .

. -, « » « ». -, . — .

.

, .

: « ».

: «—».

, , — . « » .

. , «».

.

, .

: « ».

: « , ».

, , . , , « » .

, , . , . , . , , .

.

.

: « ».

: « , ».

, , , . , — , -, - , , .

« » — , . — .

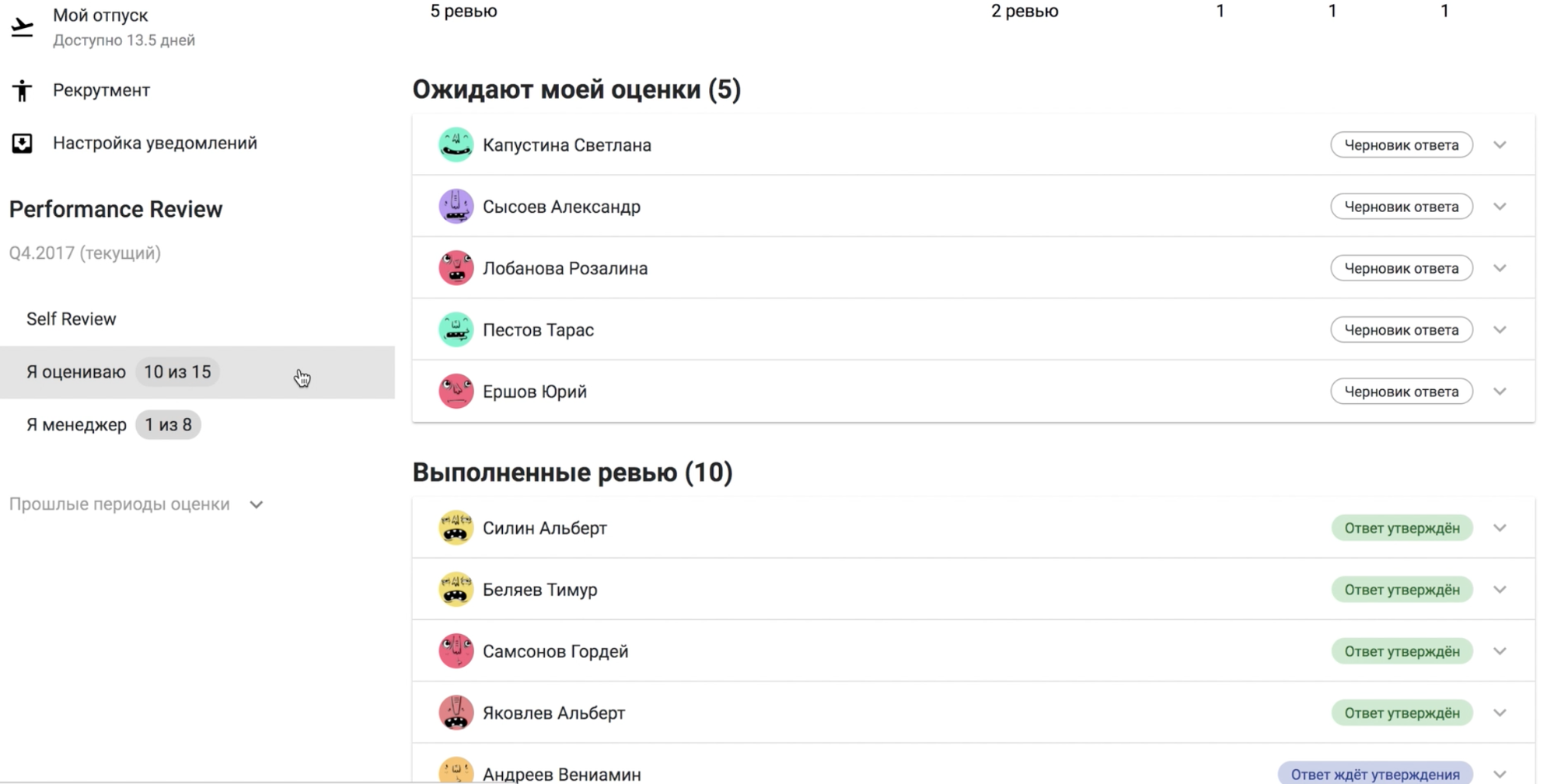

Instruments

Google Forms

, MVP. . — , , self review, . , , , . , .

— . , . — , . , , . , , . , .

— performance review . — -, , - — . - , , .

, , — , , . . , , , , .

Automation

, . , , , . - , . — , , , .

performance review , . .

performance review , . , , .

. , , . , — - . .

— , , « » « ». , , . A/B , , .

— , . , . .

, , . , .

Conclusion

, . , .

- , .

- , .

- , .

- , performance review. , .

- Self review , .

, — . performance review, . , , . , , , . , — !

Links

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/353216/

All Articles