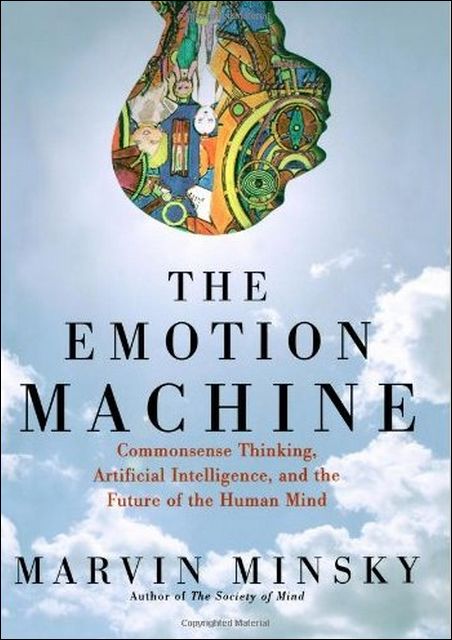

Marvin Minsky "The Emotion Machine": Chapter 1 "How we control ourselves"

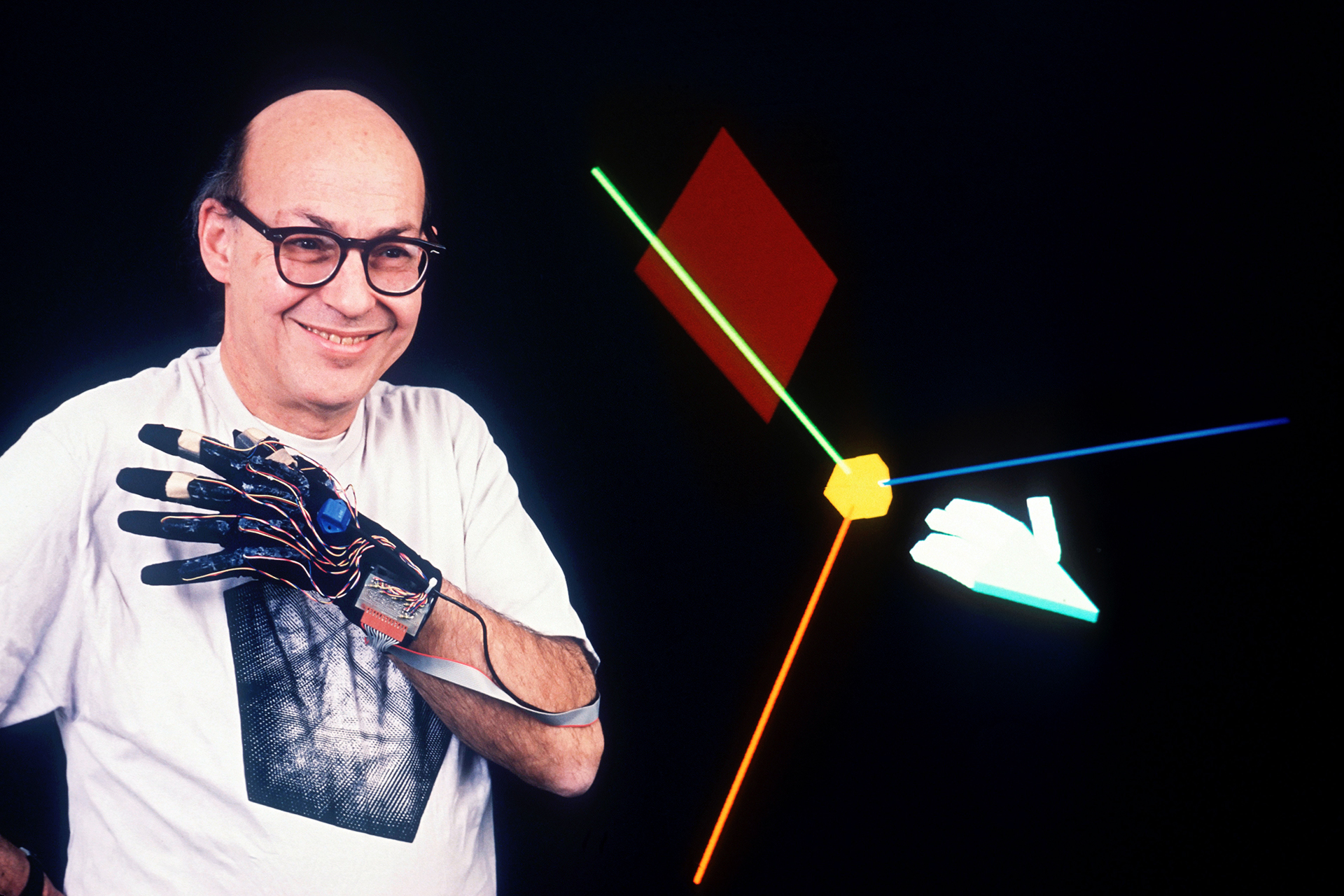

The father of artificial intelligence is thinking about how to make a machine that would be proud of us . Marvin Minsky was a rather tough scientist and the fact that he explored the theme of feelings and emotions with his “scalpel of knowledge”, which makes us human, is quite interesting and useful. The book is an excellent example of how to use the “IT approach” to try to comprehend the “human”: values, ideals, love, pain, common sense.

Previous paragraph

From time to time we dive into questions about how we manage ourselves.

')

But we cannot even hope to understand these things without adequate answers to the following questions:

In short, we need to gain a deeper understanding of the processes we call thinking. But whenever we start thinking about it, we are confronted with even more riddles.

Now everyone knows how Anger is felt, or Pleasure, Grief, Joy, Woe, in any case, as Alexander Pope believes in his work “Essay on Man”, but we still know almost nothing about how these processes actually work.

"Can he, whose rules bind a quick comet,

Describe or correct any movement of your mind?

Who has seen his fire ignite and die down

Explain its own beginning and end? ”

(Original -

“Could he, whose rules come rapid comet bind,

Describe or fix one movement of his mind?

Who saw its fires here, and there descend,

Explain his own beginning, or his end? ”)

How could we learn so much about atoms, and oceans, and planets, and stars, but so little about the mechanisms of the mind? The first was due to Newton, who discovered three simple laws describing the motion of an object, Maxwell discovered four more laws describing all electromagnetic events, and Einstein later reduced all these formulas to more compact ones. All this was made possible by the successful search for physicists: to find simple explanations for things that, at a first approximation, seemed incredibly difficult.

Then why have the sciences of the mind made much less progress during the same three centuries? I guess this was largely because most psychologists imitated physicists, trying to find the same simple explanations of mental processes. However, this strategy did not help find a small set of laws that would pretty much describe any large areas of human thought. Thus, this book will start the search from the diametrically opposite side: find more complex ways to describe mental events that seem basic and simple at the very beginning!

This policy of the book may seem absurd to scientists who have been trained to believe statements such as: "You should never accept hypotheses that make more assumptions than is necessary to describe the observed phenomenon." It’s worse to do exactly the opposite: for example, when we use “psychological words” that basically hide what they describe. Thus, each phrase in the following sentence hides the complexity of the subject:

This also applies to everyday phrases and words that we utter to describe what our mind does when someone utters the following phrase: "I think I understood what you said to me." Perhaps the most vivid example of this phenomenon is how we use words like Me and You, because we are all familiar with the following fairy tale:

Each of us is constantly controlled by powerful creatures that dwell within our mind. They make our feelings, and think for us, and make our important decisions for us. We call them Own Personality or Individuality - and we believe that they always remain the same, no matter how much we can change ourselves.

This concept of "One-I" well helps us in everyday social affairs. But this concept prevents us from thinking about what our mind is and how it works - because when we ask ourselves what exactly I do, we get the same answer to every such question:

Your “I” sees the world around you using your feelings. Then it saves what it has learned in your memory. It creates all your desires and goals - and then solves all your problems for you, using your “intellect”.

What attracts us to this strange idea, in which we ourselves do not make any decisions, but simply delegate them to someone else? Here are some reasons why the mind can support this fiction:

Child psychologist: Among the first things you learn to recognize are people in your environment. In the next step, you must assume that you yourself are also human. But it is probably much easier to conclude that a person is inside of you.

Therapist: Of course this is fiction - it makes life much more pleasant, not allowing us to notice to what extent we are controlled by conflicting, unconscious goals.

Pragmatist: This view makes us effective, while other ideas can slow down our work. In this case, it would be too long for our hardworking minds to understand anything.

However, although the concept of “One-I” has practical application, it does not allow us to understand ourselves - because it does not put at our disposal smaller parts that we could use to build a theory than we are. When you think of yourself as something single, it does not give you any information about such problems as:

Instead, the “One-I” concept may offer the following meaningless answers:

Whenever we ask questions about our mind, it happens that the easier the questions are asked - the more difficult it seems to find the answer to the questions posed. When you are asked about a complex task, for example, “How can a person build a house?”, You can respond almost instantly - “He can make a foundation, and then build walls and a roof.” However, one can hardly imagine that to answer such seemingly simple questions as:

Of course, none of the questions asked is simple. The process of “viewing” a car or a chair involves hundreds of different parts of your brain, each of which is involved in quite complex work. Then why do we not perceive this complexity? This is because many processes that are vital have evolved to work within parts of the brain that have become so quietly functioning that the rest of our brain has lost access to them. This may be the reason why it is so difficult for us to explain many things that we do very simply.

In Chapter 9, we will return to this I, and discuss how this is a large and complex structure.

Whenever you think about your “I”, you switch between a huge network of models, each of which tries to represent a specific part of your mind, in order to answer the questions you have about yourself.

For the translation, thanks to Stanislav Sukhanitsky, who responded to my call in the “previous chapter.” Who wants to help with the translation - write in a personal or mail magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

By the way, we launched the translation of another cool book - “The Dream Machine: The History of Computer Revolution” .

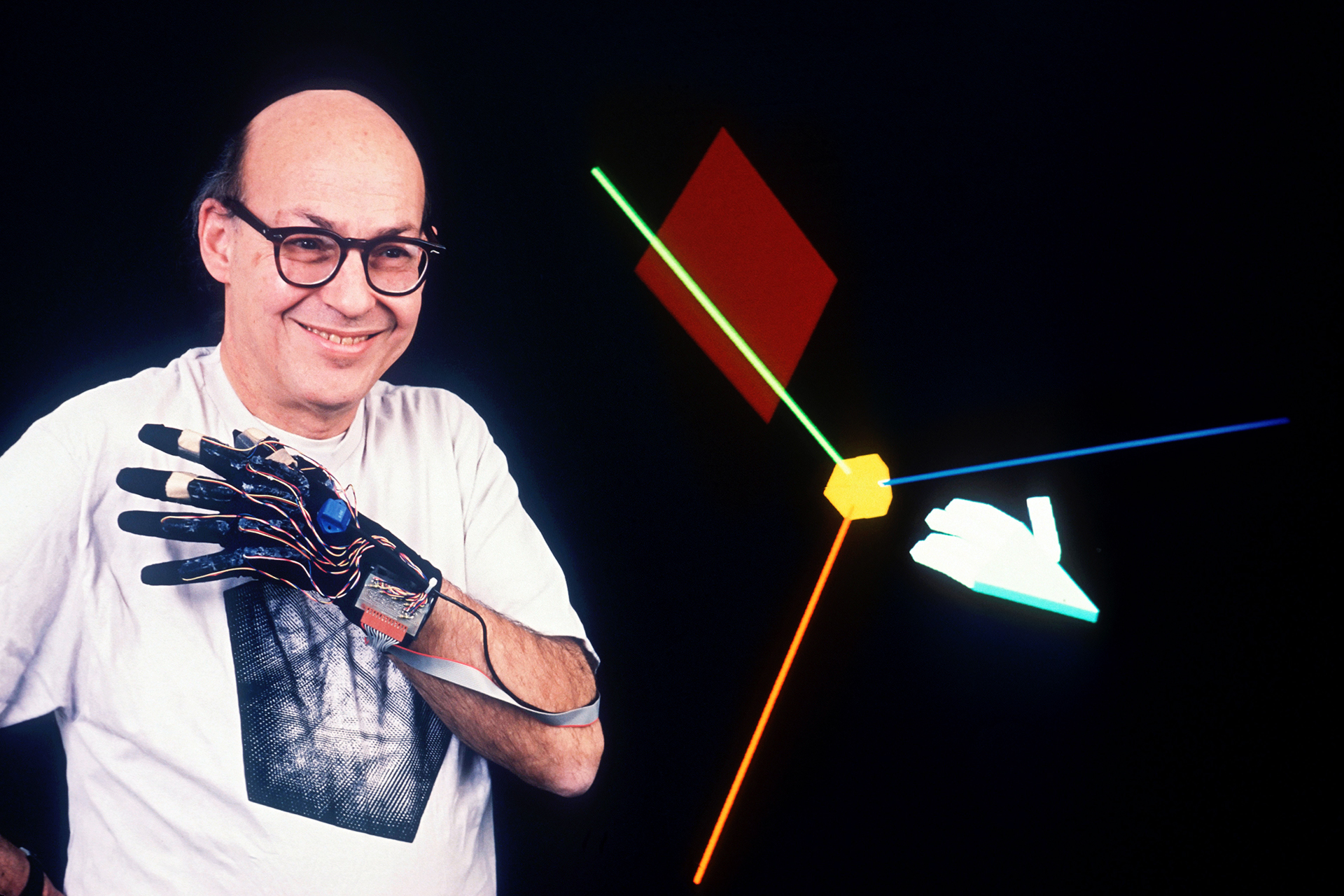

Marvin Lee Minsky (Eng. Marvin Lee Minsky; August 9, 1927 - January 24, 2016) - American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence, co-founder of the Laboratory of Artificial Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Wikipedia ]

Interesting Facts:

Previous paragraph

§1-2 Sea of Mental Secrets

From time to time we dive into questions about how we manage ourselves.

')

- Why do I spend so much of my time?

- What determines my preferences?

- Why do I have such strange fantasies?

- Why do I find math so complicated?

- Why am I afraid of heights and crowds?

- What makes me addicted to exercise?

But we cannot even hope to understand these things without adequate answers to the following questions:

- How does our mind create new ideas?

- What are the basics of our beliefs?

- How do we learn from experience?

- How do we manage to reason and think?

In short, we need to gain a deeper understanding of the processes we call thinking. But whenever we start thinking about it, we are confronted with even more riddles.

- What is the nature of Consciousness?

- What are our feelings and how do they work? How does our brain Imagine things?

- How is our body related to our mind?

- What shapes our values, goals, and ideals?

Now everyone knows how Anger is felt, or Pleasure, Grief, Joy, Woe, in any case, as Alexander Pope believes in his work “Essay on Man”, but we still know almost nothing about how these processes actually work.

"Can he, whose rules bind a quick comet,

Describe or correct any movement of your mind?

Who has seen his fire ignite and die down

Explain its own beginning and end? ”

(Original -

“Could he, whose rules come rapid comet bind,

Describe or fix one movement of his mind?

Who saw its fires here, and there descend,

Explain his own beginning, or his end? ”)

How could we learn so much about atoms, and oceans, and planets, and stars, but so little about the mechanisms of the mind? The first was due to Newton, who discovered three simple laws describing the motion of an object, Maxwell discovered four more laws describing all electromagnetic events, and Einstein later reduced all these formulas to more compact ones. All this was made possible by the successful search for physicists: to find simple explanations for things that, at a first approximation, seemed incredibly difficult.

Then why have the sciences of the mind made much less progress during the same three centuries? I guess this was largely because most psychologists imitated physicists, trying to find the same simple explanations of mental processes. However, this strategy did not help find a small set of laws that would pretty much describe any large areas of human thought. Thus, this book will start the search from the diametrically opposite side: find more complex ways to describe mental events that seem basic and simple at the very beginning!

This policy of the book may seem absurd to scientists who have been trained to believe statements such as: "You should never accept hypotheses that make more assumptions than is necessary to describe the observed phenomenon." It’s worse to do exactly the opposite: for example, when we use “psychological words” that basically hide what they describe. Thus, each phrase in the following sentence hides the complexity of the subject:

You look at an object and see what it is.For the word "look" suppresses your questions about systems that are involved in the movement of your eyes. Then the word “object” distracts you from the question of how your visual systems break the stage into different areas of colors and textures, and then associate them with various “things”. And finally, the phrase “see what it is” collapses all the questions you can ask about how this vision may be related to other things that you have seen in the past.

This also applies to everyday phrases and words that we utter to describe what our mind does when someone utters the following phrase: "I think I understood what you said to me." Perhaps the most vivid example of this phenomenon is how we use words like Me and You, because we are all familiar with the following fairy tale:

Each of us is constantly controlled by powerful creatures that dwell within our mind. They make our feelings, and think for us, and make our important decisions for us. We call them Own Personality or Individuality - and we believe that they always remain the same, no matter how much we can change ourselves.

This concept of "One-I" well helps us in everyday social affairs. But this concept prevents us from thinking about what our mind is and how it works - because when we ask ourselves what exactly I do, we get the same answer to every such question:

Your “I” sees the world around you using your feelings. Then it saves what it has learned in your memory. It creates all your desires and goals - and then solves all your problems for you, using your “intellect”.

What attracts us to this strange idea, in which we ourselves do not make any decisions, but simply delegate them to someone else? Here are some reasons why the mind can support this fiction:

Child psychologist: Among the first things you learn to recognize are people in your environment. In the next step, you must assume that you yourself are also human. But it is probably much easier to conclude that a person is inside of you.

Therapist: Of course this is fiction - it makes life much more pleasant, not allowing us to notice to what extent we are controlled by conflicting, unconscious goals.

Pragmatist: This view makes us effective, while other ideas can slow down our work. In this case, it would be too long for our hardworking minds to understand anything.

However, although the concept of “One-I” has practical application, it does not allow us to understand ourselves - because it does not put at our disposal smaller parts that we could use to build a theory than we are. When you think of yourself as something single, it does not give you any information about such problems as:

- What determines the topics that I think about?

- How to choose what to do next?

- How can I solve this difficult problem?

Instead, the “One-I” concept may offer the following meaningless answers:

- My self chooses what to think about.

- My Self decides what I should do next.

- I must try to get I to get to work.

Whenever we ask questions about our mind, it happens that the easier the questions are asked - the more difficult it seems to find the answer to the questions posed. When you are asked about a complex task, for example, “How can a person build a house?”, You can respond almost instantly - “He can make a foundation, and then build walls and a roof.” However, one can hardly imagine that to answer such seemingly simple questions as:

- How do you remember things you have already seen?

- How do you make sense of what the selected word means?

- What makes you prefer the pleasure of pain?

Of course, none of the questions asked is simple. The process of “viewing” a car or a chair involves hundreds of different parts of your brain, each of which is involved in quite complex work. Then why do we not perceive this complexity? This is because many processes that are vital have evolved to work within parts of the brain that have become so quietly functioning that the rest of our brain has lost access to them. This may be the reason why it is so difficult for us to explain many things that we do very simply.

In Chapter 9, we will return to this I, and discuss how this is a large and complex structure.

Whenever you think about your “I”, you switch between a huge network of models, each of which tries to represent a specific part of your mind, in order to answer the questions you have about yourself.

For the translation, thanks to Stanislav Sukhanitsky, who responded to my call in the “previous chapter.” Who wants to help with the translation - write in a personal or mail magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

By the way, we launched the translation of another cool book - “The Dream Machine: The History of Computer Revolution” .

Table of Contents of The Emotion Machine

Introduction

Chapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

Chapter 1. Falling in Love

Love

The Sea Of Mental Mysteries

Moods and Emotions

Infant emotions

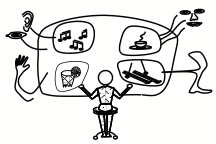

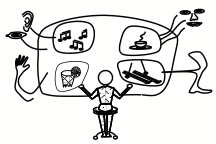

Seeing a Mind as a Cloud of Resources

Adult Emotions

Emotion cascades

Questions

The Sea Of Mental Mysteries

Moods and Emotions

Infant emotions

Seeing a Mind as a Cloud of Resources

Adult Emotions

Emotion cascades

Questions

Chapter 2. ATTACHMENTS AND GOALS

Chapter 3. FROM PAIN TO SUFFERINGChapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

about the author

Marvin Lee Minsky (Eng. Marvin Lee Minsky; August 9, 1927 - January 24, 2016) - American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence, co-founder of the Laboratory of Artificial Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Wikipedia ]

Interesting Facts:

- Minsky was a friend of critic Harold Bloom from Yale University (Yale University), who spoke of him as “sinister Marvin Minsky”.

- Isaac Asimov described Minsky as one of two people who are smarter than himself; the second, in his opinion, was Karl Sagan.

- Marvin is a robot with artificial intelligence from the cycle of Douglas Adams novels Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (film).

- Minsky has a contract to freeze his brain after death in order to be “resurrected” in the future.

- In honor of Minsk named the dog of the protagonist in the movie Tron: Legacy. [ Wikipedia ]

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/353202/

All Articles