Marvin Minsky "The Emotion Machine": Chapter 2 "Playing With the Mud"

2.1. Playing with dirt

“This is not just learning the things that matter. This is learning what to do with what you learn and how you learn all these important things. ”- Norton Jaster, The Phantom Tollbooth

A child named Carol plays with dirt. Equipped with a fork, spoon and cup, her task is to bake an imaginary cake, in the same way as cooking her mother. Let's assume that she plays alone and imagine three things that can happen to her:

She plays alone . She wants to fill her cup with dirt and first does it with her fork, but she fails because the dirt seeps through the teeth of the fork. She is disappointed and feels frustration. But when she gets her way through the use of a spoon, Carol is happy and satisfied.

')

What can Carol learn from this situation? She gained knowledge through trial and error that the forks were not very suitable for carrying dirt. But thanks to the experience with the spoon, she gained the knowledge that spoons are a good tool for carrying liquids. Due to mistakes, we understand which method does not work - while success teaches us which method will bring success. [Explained in §9-2.]

Notice that Carol did this when she worked alone — and gained new knowledge on her own. In the case of trial and error, she did not need a teacher to assist.

She is scolded by a stranger . Suddenly, a stranger reproaches her: "This is an inappropriate act." Carol feels anxiety, anxiety and fear. Overcoming fear and desire to run away, she delays the fulfillment of her current goal - and runs away to look for her mother.

What can Carol understand from this situation? She may not understand how to work with dirt, but she can classify this place as dangerous. Also, too many such scary events can make it less adventurous.

Her mother reproaches . Carol returns to her mother for help, but instead of protecting her, her parent blames her. “What a terrible mess you made! Look what you did with your things and your face. I can barely look at you! ”Carol, ashamed, begins to cry.

What can Carol understand from this situation? She will be less inclined to play with dirt. If the parent chooses to praise her instead, she will feel pride instead of shame - and in the future she will be more inclined to start this game. Facing the guilt or reproach of her parents, she realizes that her goal is not very good for realization.

Think of the huge amount of emotional experiences a child gets involved in thousands of minutes each day! In this very short story, we have touched upon such experiences as satisfaction, aspiration, and pride — emotions that we regard as positive. We also mentioned shame and shame - and fear, anxiety, and anxiety - all the feelings that we consider negative. What can be the functions of these different states of mind? Why do they turn out to be in opposite pairs? How can the physical systems in our brain reproduce such sensations and thoughts? This book will try to answer many similar questions, but this chapter will mainly focus on some ideas about the functions of our children’s early attachments to other people.

It is clear that attachment to adults helps young animals to survive thanks to their nutrition, comfort and protection from threats. However, this chapter argues that these special feelings of pride and shame play a unique and peculiar role in how we develop new kinds of goals. And due to the fact that the minds of adults are much more complicated, we will begin by discussing the actions of children.

2.2 Applications and objectives

“Never let your sense of morality stop you from doing the right thing.”

- Isaac Asimov

Some of our strongest emotions pass away when we are in the presence of the person to whom we are attached. Being exalted or blamed by the people we love, we don’t feel flattered or dissatisfied; We tend to feel proud or ashamed. This section will suggest some possible reasons why we may have these specific feelings, as well as some ways that may be involved in how our values and goals develop.

Most other mammals, shortly after birth, can move and follow their mothers, but the children of people are especially helpless. Why are our babies forced to grow so slowly? In part, this may be due to the fact that their big brains need more time to mature. Also, since the use of more universal brains led to the creation of complex societies, our children had to develop new ways to effectively “load” knowledge; they no longer have time to learn through trial and error.

One way to learn faster was to develop improved abilities to observe and describe what other adults are doing. Another newest invention was “learning through story” —the use of various expressions that ultimately led to the creation of our languages. Both of these achievements were further improved by two additional events: the children gained increased concern about how parents respond to their behavior, and the parents gained increased concern about the well-being of their children.

Both of these events are powerful tools for capturing other people's attention. For example, our babies are born with screams that woke their parents from deep sleep. These cries cannot be ignored because, compared to other loud sounds, they exploit the connection with the experience of pain, which activates powerful tools for finding ways to remove these stimuli. Another similar system makes children feel anxious when their parents go too far - and parents of people feel a similar feeling of pain when they lose information about the finding of their children. We can observe how some of these systems can work by redefining some of the learning patterns of Carol.

In the scenario where Carol played alone, when using a fork did not give results on filling her cup. Her upset state allowed her to gain knowledge that you should not use that cup filling method again. But when she got satisfied with the successful experience with a spoon, her satisfaction helped her to understand that this method is much better to use - so the next time she wants to fill the cup, she will know more about how this can be done.

In this case, Carol was trained through trial and error, without any help from a teacher who would help her. What could have prompted her to continue to persist in achieving the goal, despite the first disappointing results? In paragraph 9-2, we will return to the discussion of why we sometimes put up with the troubles that arise.

In the script, when a stranger appeared, Carol felt fear. This led her to look for ways to escape and parental protection.

This situation probably did not affect her goal of learning how to move the dirt into the cup - and, most likely, taught her to beware of this place. Next time she will play in a safer place.

In the script, when Carol's mother scolded her, the child felt shame - a special kind of emotion. It changed the nature of what she learned: she changed her goals, instead of changing her methods!

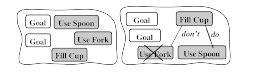

Why did Carol gain completely different knowledge after censuring her mother? This accusation made the child feel the following sensation: “I should not have put such inappropriate goals”. But when her mother admires her, Carol feels that her goal was worthy. One thing is to learn how to get what you want, and another is to find out what you should want. In practical trial and error training, you improve your skill to achieve the goals you are pursuing — for example, bringing new sub-goals to it. But when your feelings of “self-knowledge” are prompted, you can probably change these goals on your own or make changes to related sub-goals.

Trial and error can teach us new ways to achieve those goals that we already adhere to.

The accusation and praise connected with the result of activity teach us what goals can be eliminated and which can be saved.

This suggests that pride and shame play a special role in what we learn. They help us learn “what it means in the end” ('ends') instead of “what it means” ('means'). Listen to Michael Lewis, who describes some of the striking effects of feeling ashamed:

“Shame manifests itself when an individual judges his actions as a failure to comply with his own standards, rules and goals, and gives them a global assessment. A person who is ashamed wants to hide, disappear or die. It is an extremely negative and painful experience, interrupting existing behavior and causing confusion in thoughts and inability to speak. The body of a person experiencing shame seems to be compressed, as if disappearing from the eyes and eyes of others. Because of the intensity of emotional experience and the extensive attack on themselves, all that these people can do in a state of shame is to try to rid themselves of this sensation. ”

But when do we feel such intense sensations? They are exclusively manifested when we are in the company of people whom we respect or are in the company of people among whom we want to be respected. This suggests that shame and pride may be related to the way in which we achieve our highest goals, and that those who we feel affection to — to a large extent — affect the achievement of these goals — in any case, it is for early "formative" years of life.

- What are goals and how do they work?

- What are the gaps of these “formative” years?

- To whom do our children become attached?

- When and how do we outgrow our sense of affection?

- How do they help establish our value?

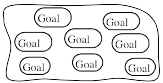

We almost always have some goals. Any time you are hungry, we try to find food. When we sense danger, we try to avoid it. When we feel offended, we may desire revenge. Sometimes you aim at doing some work, or suppose you are looking for ways to avoid it. We use words like try, make efforts, desire, aim, search and want so often that it seems that our brain is controlled by a set of goals.

The following describes a very simple idea that the words want and desire may indicate:

You “want” to reach situation G, when some active mental process works to reduce the difference between situation G and the situation in which you are now.

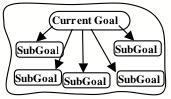

Later, in paragraph 6-3, we will see this view much more powerful than it seems at first glance. For example, when there are several things that should be removed, then achieving goal G can take several steps. For example, suppose you are hungry and hungry, but you only have a can of soup. In this case, you must find some tool to open this jar, and then try to find a bowl and a spoon, and then you will want to eat. Each of these “needs” results from some differences between the situation in which you find yourself and the one you want to achieve - so that each such difference in situations becomes a sub-goal of your original goal.

Of course, you first need to make a plan for all these tasks — and creating these plans can sometimes involve significant portions of the remnants of your mind.

The Philistine: Why are we focusing so strongly on goals, as if everything we are doing is done purposefully? Sometimes we simply react to what is happening around, or execute old, familiar algorithms, and sometimes we simply dream and fantasize, or aimlessly present things.

It will be extremely difficult to prove that any human activity is completely devoid of any goals, because, as Sigmund Freud observed, some of our mental processes can work to hide the main motives and goals from ourselves. But in any case, we need more understanding about how we form such intentions.

The most common theory of how people learn is what we call trial and error. This theory describes how Carol studied when she played alone, when she played with herself, filling the cup. She was annoyed when she couldn’t achieve her goal with a fork, but was satisfied with the success when she used the spoon — so the next time she wants to fill the cup, she is more likely to know what to do. It seems simple common sense - we learn from mistakes and successes, but we need a theory of how this can work.

Student: I assume that her brain forms the connections between her goal and the actions that helped her achieve her goal.

Good, but it is extremely vague. Can you tell more about how this works?

Student: Carol may have started with some goals that were around her, but then, when she succeeded in using the spoon, she somehow connected her goal to “Fill the cup” with the goal of “Use the Spoon”. Also, when she didn’t work with a fork, she created a “do not fit” connection with the goal of “Use the Plug”, to prevent the use of this event again. Then, the next time she wants to fill the cup, she will first try to use the sub-goal with a spoon.

This would be a good start, and I would like to mention these compounds "not fit." This is important because we must not only learn how to do things that work, but we must also avoid the most common mistakes.

However, while these types of theories can help explain how we connect our goals, which we already have, it does not answer such questions as: “How do we set new goals that are not sub-goals of existing goals?” Or, to put it more Overall: “How do we learn new ideas and skills?”

I do not remember many such discussions in books on academic psychology. In the following sections, we will discuss that we cannot acquire our highest level values in the same way that we learn other things, that is, we learn from experience.

For the translation, thanks to Stanislav Sukhanitsky, who responded to my call in the “previous chapter.” Who wants to help with the translation - write in a personal or mail magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

By the way, we launched the translation of another cool book - “The Dream Machine: The History of Computer Revolution” .

Table of Contents of The Emotion Machine

Introduction

Chapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

Chapter 1. Falling in Love

Love

The Sea Of Mental Mysteries

Moods and Emotions

Infant emotions

Seeing a Mind as a Cloud of Resources

Adult Emotions

Emotion cascades

Questions

The Sea Of Mental Mysteries

Moods and Emotions

Infant emotions

Seeing a Mind as a Cloud of Resources

Adult Emotions

Emotion cascades

Questions

Chapter 2. ATTACHMENTS AND GOALS

Chapter 3. FROM PAIN TO SUFFERINGPlaying with mud

Attachments and Goals

Imprimers

Attachment-Learning Elevates Goals

Learning and pleasure

Conscience, Values and Self-Ideals

Attachments of Infants and Animals

Who are our Imprimers?

Self-Models and Self-Consistency

Public imprimers

Attachments and Goals

Imprimers

Attachment-Learning Elevates Goals

Learning and pleasure

Conscience, Values and Self-Ideals

Attachments of Infants and Animals

Who are our Imprimers?

Self-Models and Self-Consistency

Public imprimers

Chapter 4. CONSCIOUSNESS

Chapter 5. LEVELS OF MENTAL ACTIVITIES

Chapter 6. COMMON SENSE

Chapter 7. Thinking.

Chapter 8. Resourcefulness.

Chapter 9. The Self.

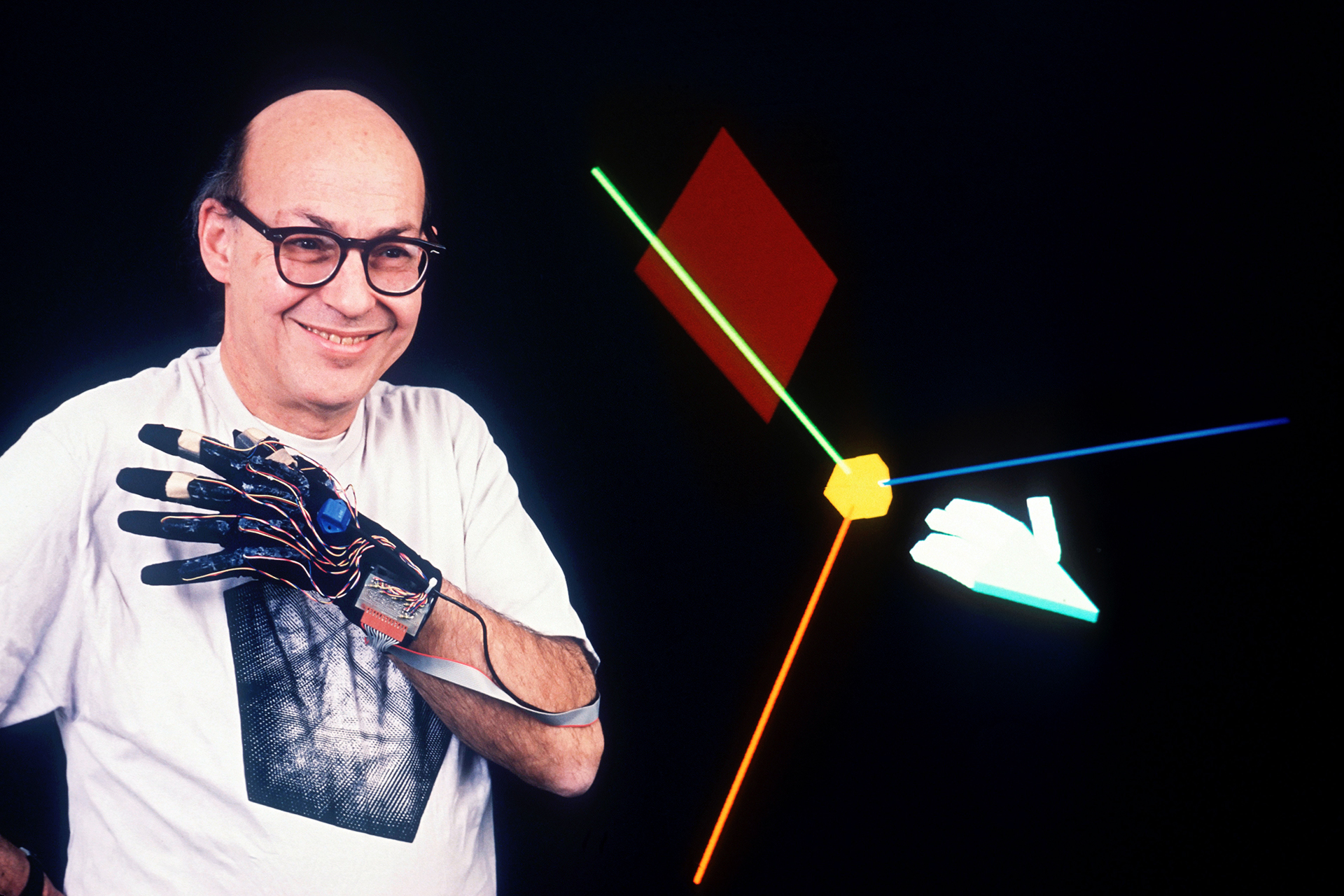

about the author

Marvin Lee Minsky (Eng. Marvin Lee Minsky; August 9, 1927 - January 24, 2016) - American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence, co-founder of the Laboratory of Artificial Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Wikipedia ]

Interesting facts:

- Minsky was a friend of critic Harold Bloom from Yale University (Yale University), who spoke of him as “sinister Marvin Minsky”.

- Isaac Asimov described Minsky as one of two people who are smarter than himself; the second, in his opinion, was Karl Sagan.

- Marvin is a robot with artificial intelligence from the cycle of Douglas Adams novels Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (film).

- Minsky has a contract to freeze his brain after death in order to be “resurrected” in the future.

- In honor of Minsk named the dog of the protagonist in the movie Tron: Legacy. [ Wikipedia ]

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/351760/

All Articles