How to learn to learn. Part 3 - we train memory "on a science"

We continue the story about what technology, confirmed by scientific experiments, can help in learning at any age. In the first part, we discussed the obvious recommendations, such as “competent daily routine” and other attributes of a healthy lifestyle. The second part dealt with how doodling helps to better record material in a lecture, and reasoning about the upcoming exam allows you to get a higher score.

Today we are talking about which scientific advice helps memorize information more efficiently, and forget important information - more slowly.

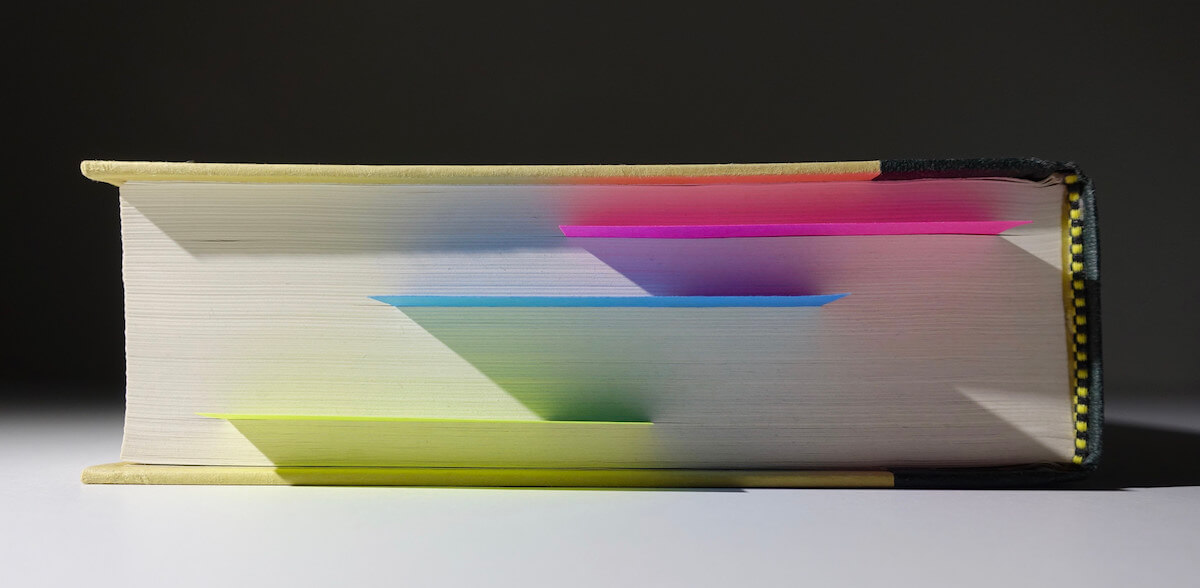

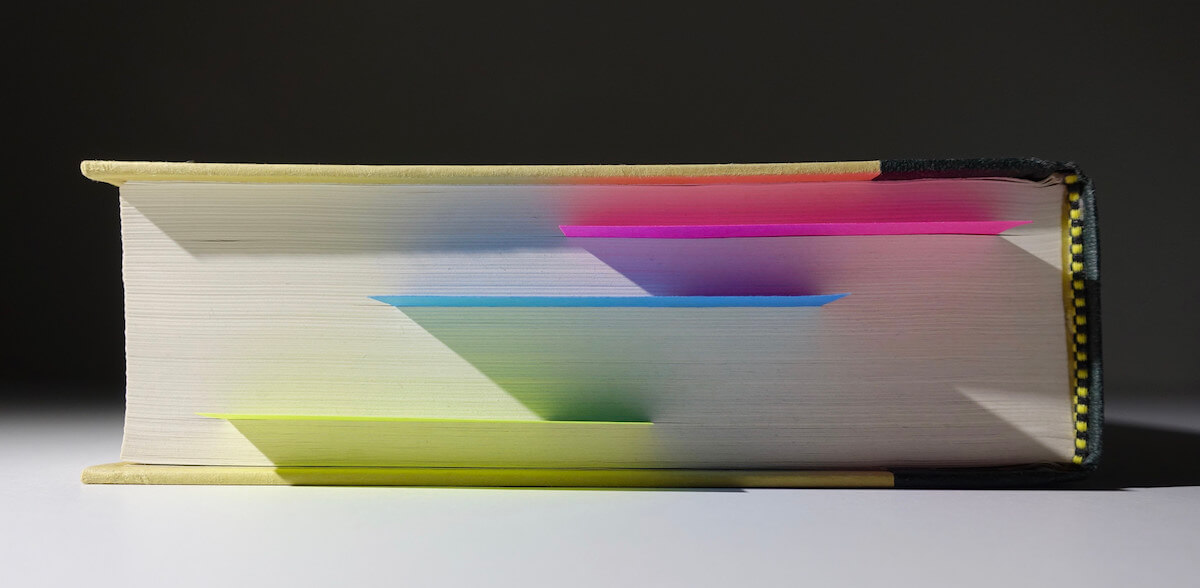

Photo by Dean Hochman CC BY

Photo by Dean Hochman CC BY

')

One way to better memorize information (for example, before an important exam) is storytelling. We will understand why. Storytelling - “conveying information through history” - is a technique that is now popular in a huge number of areas: from marketing and advertising to publications in the non-fiction genre. Its essence, in its most general form, lies in the fact that the narrator turns a set of facts into a narrative, a sequence of interrelated events.

Such stories are perceived much easier than weakly interconnected data, so the technique can be used when memorizing material - try to build the information you need to remember in the story (or even a few stories). Of course, such an approach requires creativity and considerable effort - especially if necessary, for example, to memorize the proof of the theorem - when it comes to formulas, it becomes difficult for stories.

However, in this case, you can use techniques that are indirectly related to storytelling. One option is offered, in particular, by scientists from Columbia University (USA), who published last year the results of their research in the journal Psychological Science.

Specialists who worked on the study, studied the impact of a critical approach to the evaluation of information on the ability to perceive and memorize data. The critical approach is somewhat like an argument with an “internal skeptic” who is not satisfied with your arguments and which questions everything you say.

How the study was conducted: 60 students participating in the experiment provided input data. They included information on the “election of the mayor in some city X”: the political programs of the candidates and a description of the problems of the fictional town. The control group was asked to write an essay about the merits of each of the candidates, and the experimental group was asked to describe the dialogue between the participants of the political show discussing the candidates. Both groups (control and experimental) were then offered to write a script for a television presentation in favor of the candidate they liked.

It turned out that in the final scenario, the experimental group provided more facts, used more accurate formulations and demonstrated a better understanding of the material. In the TV ad text, students from the experimental group demonstrated the differences between the candidates and their programs and provided more information about how the candidate you liked was going to solve urban problems.

Moreover, the experimental group expressed its ideas more precisely: among all the students of the experimental group, only 20% resulted in statements in the final scenario of a TV-roller, not confirmed by facts (ie, input data). In the control group, 60% of students made such statements.

As the authors of the article declare , the elaboration of various critical opinions on a particular issue contributes to its more thorough study. This approach influences how you perceive information - “internal dialogue with a critic” allows you not only to take knowledge on faith. You begin to look for alternatives, give examples and proofs - and thus get a deeper understanding of the question and memorize more useful details.

Such an approach, for example, helps to better prepare for tricky questions in the exam. Of course, you will not be able to predict everything that a teacher may ask you, but you will feel much more confident and prepared - because you have already “lost” in your head similar situations.

If “talking to yourself” is a good way to better understand information, then knowing how the forgetting curve works (and how to deceive it) will help to hold useful information as long as possible. Ideally, to keep the knowledge gained at the lecture, right up to the exam (and, more importantly, after it).

The forgetting curve is not a new discovery; for the first time this term was introduced by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885. Ebbingauz was studying mechanical memory and was able to deduce patterns between the time from the moment of receiving data, the number of repetitions and the percentage of information that ultimately remains in memory.

Ebbingauz conducted experiments on the training of "mechanical memory" - by memorizing meaningless syllables that should not cause any associations in memory. It is extremely difficult to memorize nonsense (such sequences are "weathered" from memory very easily) - however, the forgetting curve "works" also in relation to quite meaningful, meaningful data.

Photo torbakhopper CC BY

For example, with regard to a university course, you can interpret the forgetting curve as follows: immediately after attending a lecture, you have a certain amount of knowledge. It can be designated as 100% (roughly speaking, “you know everything that you know”).

If the next day you do not return to your lecture notes and do not repeat the material, then by the end of this day only 20-50% of all information received at the lecture will remain in your memory (again, this is not a share of all the information that the teacher gave at the lecture , and from everything that you personally managed to memorize at the lecture). In a month with this approach, you will be able to recall about 2-3% of the information received - as a result, before the exam you will have to thoroughly sit down at the theory and learn the tickets from almost nothing.

The way out here is quite simple - in order not to memorize information “like the first time,” it is enough to regularly repeat it from records from lectures or from textbooks. Of course, this is a rather boring procedure, but it can save a lot of time before exams (and securely consolidate knowledge in long-term memory). Repetition in this case is a clear signal to the brain that this information is really important. As a result, the approach will allow both to preserve knowledge better and “activate” access to it at the right moment more quickly.

For example, the Canadian University of Waterloo advises its students to follow the following tactics: “The main recommendation is to give a repetition of about half an hour on weekdays and one and a half to two hours on weekends. Even if you can repeat information only 4-5 days a week, you still remember a lot more than 2-3% of the data that would remain in your memory if you didn’t do anything at all. ”

Today we are talking about which scientific advice helps memorize information more efficiently, and forget important information - more slowly.

Photo by Dean Hochman CC BY

Photo by Dean Hochman CC BY')

Storytelling - memorization through understanding

One way to better memorize information (for example, before an important exam) is storytelling. We will understand why. Storytelling - “conveying information through history” - is a technique that is now popular in a huge number of areas: from marketing and advertising to publications in the non-fiction genre. Its essence, in its most general form, lies in the fact that the narrator turns a set of facts into a narrative, a sequence of interrelated events.

Such stories are perceived much easier than weakly interconnected data, so the technique can be used when memorizing material - try to build the information you need to remember in the story (or even a few stories). Of course, such an approach requires creativity and considerable effort - especially if necessary, for example, to memorize the proof of the theorem - when it comes to formulas, it becomes difficult for stories.

However, in this case, you can use techniques that are indirectly related to storytelling. One option is offered, in particular, by scientists from Columbia University (USA), who published last year the results of their research in the journal Psychological Science.

Specialists who worked on the study, studied the impact of a critical approach to the evaluation of information on the ability to perceive and memorize data. The critical approach is somewhat like an argument with an “internal skeptic” who is not satisfied with your arguments and which questions everything you say.

How the study was conducted: 60 students participating in the experiment provided input data. They included information on the “election of the mayor in some city X”: the political programs of the candidates and a description of the problems of the fictional town. The control group was asked to write an essay about the merits of each of the candidates, and the experimental group was asked to describe the dialogue between the participants of the political show discussing the candidates. Both groups (control and experimental) were then offered to write a script for a television presentation in favor of the candidate they liked.

It turned out that in the final scenario, the experimental group provided more facts, used more accurate formulations and demonstrated a better understanding of the material. In the TV ad text, students from the experimental group demonstrated the differences between the candidates and their programs and provided more information about how the candidate you liked was going to solve urban problems.

Moreover, the experimental group expressed its ideas more precisely: among all the students of the experimental group, only 20% resulted in statements in the final scenario of a TV-roller, not confirmed by facts (ie, input data). In the control group, 60% of students made such statements.

As the authors of the article declare , the elaboration of various critical opinions on a particular issue contributes to its more thorough study. This approach influences how you perceive information - “internal dialogue with a critic” allows you not only to take knowledge on faith. You begin to look for alternatives, give examples and proofs - and thus get a deeper understanding of the question and memorize more useful details.

Such an approach, for example, helps to better prepare for tricky questions in the exam. Of course, you will not be able to predict everything that a teacher may ask you, but you will feel much more confident and prepared - because you have already “lost” in your head similar situations.

Forgetting curve

If “talking to yourself” is a good way to better understand information, then knowing how the forgetting curve works (and how to deceive it) will help to hold useful information as long as possible. Ideally, to keep the knowledge gained at the lecture, right up to the exam (and, more importantly, after it).

The forgetting curve is not a new discovery; for the first time this term was introduced by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885. Ebbingauz was studying mechanical memory and was able to deduce patterns between the time from the moment of receiving data, the number of repetitions and the percentage of information that ultimately remains in memory.

Ebbingauz conducted experiments on the training of "mechanical memory" - by memorizing meaningless syllables that should not cause any associations in memory. It is extremely difficult to memorize nonsense (such sequences are "weathered" from memory very easily) - however, the forgetting curve "works" also in relation to quite meaningful, meaningful data.

Photo torbakhopper CC BY

For example, with regard to a university course, you can interpret the forgetting curve as follows: immediately after attending a lecture, you have a certain amount of knowledge. It can be designated as 100% (roughly speaking, “you know everything that you know”).

If the next day you do not return to your lecture notes and do not repeat the material, then by the end of this day only 20-50% of all information received at the lecture will remain in your memory (again, this is not a share of all the information that the teacher gave at the lecture , and from everything that you personally managed to memorize at the lecture). In a month with this approach, you will be able to recall about 2-3% of the information received - as a result, before the exam you will have to thoroughly sit down at the theory and learn the tickets from almost nothing.

The way out here is quite simple - in order not to memorize information “like the first time,” it is enough to regularly repeat it from records from lectures or from textbooks. Of course, this is a rather boring procedure, but it can save a lot of time before exams (and securely consolidate knowledge in long-term memory). Repetition in this case is a clear signal to the brain that this information is really important. As a result, the approach will allow both to preserve knowledge better and “activate” access to it at the right moment more quickly.

For example, the Canadian University of Waterloo advises its students to follow the following tactics: “The main recommendation is to give a repetition of about half an hour on weekdays and one and a half to two hours on weekends. Even if you can repeat information only 4-5 days a week, you still remember a lot more than 2-3% of the data that would remain in your memory if you didn’t do anything at all. ”

TL; DR

- To better remember the information, try using the storytelling technique. When you link facts to history, narrative, you memorize them better. Of course, such an approach requires serious preparation and is not always effective - it is difficult to come up with a story if you have to memorize mathematical proofs or formulas in physics.

- In this case, a good alternative to the "traditional" storytelling is a dialogue with yourself. To better understand the subject, try to imagine that an imaginary interlocutor objects to you, and you try to convince him. This format is more versatile, and at the same time has a number of positive features. First, it stimulates critical thinking (you do not take for granted the facts you are trying to memorize, but look for evidence that confirms your point of view). Secondly, this method allows a deeper understanding of the issue. Thirdly (which is especially useful on the eve of the exam), this technique allows you to rehearse tricky questions and potential bottlenecks in your answer. Yes, such a rehearsal can take a lot of time, but in some cases it is much more effective than an attempt to mechanically memorize the material.

- Speaking of mechanical memorization - remember the forgetting curve. Repetition of the material studied (for example, on the lecture notes) for at least 30 minutes daily will allow you to keep most of the information in memory - so that before the exam you don’t have to learn the topic from scratch. Employees of the University of Waterloo advised to experiment and test the technique of such a repetition for at least two weeks - and to monitor their results.

- And if you are worried that your notes are not very informative, try the techniques we wrote about in past materials .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/349908/

All Articles