Interesting surprises ConcurrentDictionary (+ analysis of the problem with DotNext 2017 Moscow)

Hello everyone who writes code for .NET, especially multi-threaded. You rarely see thread-safe code without thread-safe collections, which means you need to be able to use them. I will tell about the most popular of them - ConcurrentDictionary. There are surprisingly many interesting surprises hidden in it: both pleasant and not so much.

First we will analyze the ConcurrentDictionary device and the computational complexity of operations with it, and then we will talk about convenient tricks and pitfalls associated with memory traffic and garbage collection.

Field of applicability

All the observations from this article are checked for the latest version of the .NET Framework (4.7.1) at the time of publication. They are probably valid in .NET Core, but the verification of this statement remains an exercise for the reader.

Briefly about the device

Under the hood, ConcurrentDictionary has a familiar hash table implementation. It is based on an array of so-called buckets, each of which corresponds to a specific set of hash function values. Inside each bucket, there is a simply linked list of elements: in the event of a collision, a linear key search is performed in it.

Thread safety is provided by a technique called striped locking . There is a small array of ordinary locks, and each of them is responsible for a whole range of buckets (hence the stripe in the name). In order to write something into an arbitrary bucket, you need to capture the corresponding lock. Usually, locks are much smaller than buckets.

And this is how these concepts correlate with the parameters of the ConcurrentDictionary(int concurrencyLevel, int capacity) constructor ConcurrentDictionary(int concurrencyLevel, int capacity) :

capacity- the number of buckets. The default is 31.concurrencyLevel- the number of locks. The default is 4 × number of cores.

The implementation tries to keep the size of buckets small, increasing their number as needed. When expanding, the following occurs:

- Capacity approximately doubles. Approximately, because the value is chosen so that it is not divided by 2, 3, 5 and 7 ( it is useful to make the capacity simple or poorly factorizable).

- The number of locks is doubled if

concurrencyLevelnot explicitly set. Otherwise, it remains the same.

Complexity of operations

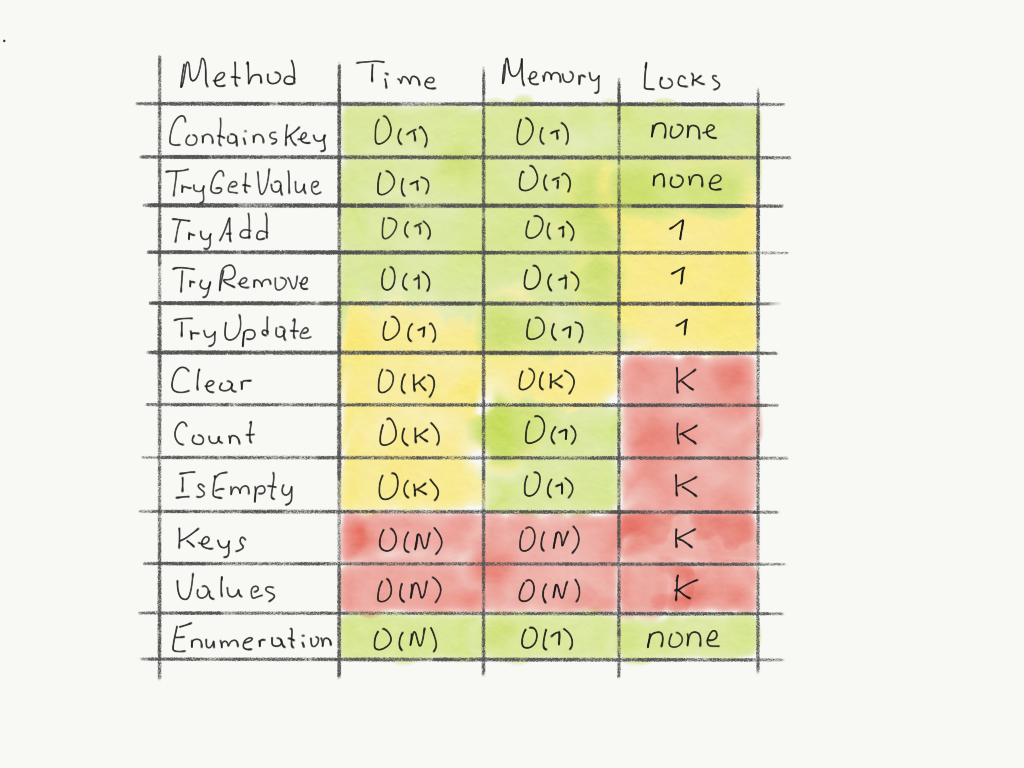

Summary plate for a dictionary with N elements and K locks:

The remaining operations are derived from these:

GetOrAdd=TryGetValue+TryAddAddOrUpdate=TryGetValue+TryAdd+TryUpdateIndexer(get)=TryGetValueIndexer(set)=TryAddwith overwriting

The bad news

The Count and IsEmpty properties cunningly capture all lok in the dictionary. It is better to refrain from frequently invoking these properties from multiple threads.

The Keys and Values properties are even more insidious: they not only take all locks, but also completely copy all keys and values into a separate List . Unlike traditional Dictionary, whose properties of the same name return thin wrappers, here you need to be ready for large memory allocations.

Such a blatant inefficiency is caused by the desire to provide the semantics of a snepshot: to return some consistent state that existed at a certain point in time.

Good news

Not so bad. First: the most common enumeration (working through GetEnumerator) is non-blocking and works without unnecessary copying of data. This has to be paid for by the lack of snapshot semantics: as a result of the transfer, the recording operations performed in parallel can be reflected in the result.

The second good news: most often this behavior is either permissible or desirable, and this can be used. For example, it is effective to list keys or values:

var keys = dictionary.Select(pair => pair.Key); var values = dictionary.Select(pair => pair.Value); Tips and tricks

Unlike the usual Dictionary, you can insert into or delete from the ConcurrentDictionary directly during the listing! This, for example, allows you to conveniently clean obsolete items from the dictionary cache with a lifetime:

foreach (var pair in cache) { if (IsStale(pair.Value)) { cache.TryRemove(pair.Key, out _); } } You can delete elements not only by key, but also by exact match key + value, and atomically! This is an undocumented feature hidden behind the explicit implementation of the ICollection interface. It allows you to safely clear such a cache, even in race conditions with updating values:

var collection = cache as ICollection<KeyValuePair<MyKey, MyValue>> foreach (var pair in cache) { if (IsStale(pair.Value)) { // Remove() will return false in case of race with value update var removed = collection.Remove(pair); } } Everyone knows this, but I remind you: in a competitive access environment, GetOrAdd can call a delegate factory for one key much more than once. If it is impossible or expensive to do this, it’s enough to wrap the value in Lazy:

var dictionary = new ConcurrentDictionary<MyKey, Lazy<MyValue>>(); var lazyMode = LazyThreadSafetyMode.ExecutionAndPublication; var value = dictionary .GetOrAdd(key, _ => new Lazy<MyValue>(() => new MyValue(), lazyMode)) .Value; Gc overhead

When using large dictionaries (starting from tens of thousands of elements), you need to remember that, unlike the usual Dictionary, the ConcurrentDictionary creates an additional object on the heap for each element. Resident ConcurrentDictionary with tens of millions of elements can easily provide second pauses when collecting second-generation garbage.

// Only a handful of objects in final dictionary. // Value types dominate in its internals. Dictionary<int, int> ordinary = Enumerable .Range(0, 10 * 1000 * 1000) .ToDictionary(i => i, i => i); // ~10kk objects in concurrent version (due to linked lists). var concurrent = new ConcurrentDictionary<int, int>(ordinary); When overwriting an existing value, a new object may also be allocated, generating memory traffic. This happens when the standard language does not guarantee the atomicity of the value type entry. For example:

- If the value is an int or reference type, its entry is atomic. Then overwriting is done in-place, without selecting a new object.

- If the value is Guid or another “wide” value type, its entry is not atomic. Here the implementation has to create a new internal object.

Task for DotNext 2017 Moscow

I first published this article in the fall of 2017 in the internal social network. And colleagues , who were at the DotNext conference in Moscow last November, did a task based on the article that could be solved at the Kontur stand.

There was a code snippet:

public void TestIteration(ConcurrentDictionary<int, int> dictionary) { Parallel.For(0, 1000, new ParallelOptions { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = 8 }, (i) => { foreach (var keyValuePair in dictionary) { dictionary.AddOrUpdate(keyValuePair.Key, (key) => i, (key, value) => i); } }); } public void TestKeysProperty(ConcurrentDictionary<int, int> dictionary) { Parallel.For(0, 1000, new ParallelOptions { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = 8 }, (i) => { foreach (var key in dictionary.Keys) { dictionary.AddOrUpdate(key, (k) => i, (k, value) => i); } }); } And three questions - it was necessary to compare the effectiveness of the TestIteration and TestKeysProperty methods by the number of operations, by memory and by runtime. If you carefully read the article, it should be clear that in all three cases, TestIteration is more efficient.

findings

Concurrent programming tools are full of unobtrusive subtleties when it comes to performance: if you carelessly use ConcurrentDictionary, for example, you may encounter global locks and linear cost in memory. I hope this cheat sheet will help you not to step on the rake when writing the next cache or index in your application.

All good and effective code!

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/348508/

All Articles