Extended Validation not working

Extended Validation Certificates (“EV”) are a unique type of certificate issued by certification authorities after more thorough verification of the entity requesting a certificate. In exchange for this more rigorous verification, browsers show a special indicator, such as a green bar containing the company name, or, in the case of Safari, completely replace the URL with the company name.

As a rule, this process works quite well, and erroneously issued certificates are few. However, the problems are more than enough. EV certificates contain information about the legal entity behind the certificate, but no more. The name of the legal entity, however, may be quite variable; For example, James Burton recently received an EV certificate for his company “Identity Verified” (English Authenticity Verified - approx. Transl.) . Unfortunately, users simply do not have the opportunity to see and understand such features, and this creates considerable scope for phishing.

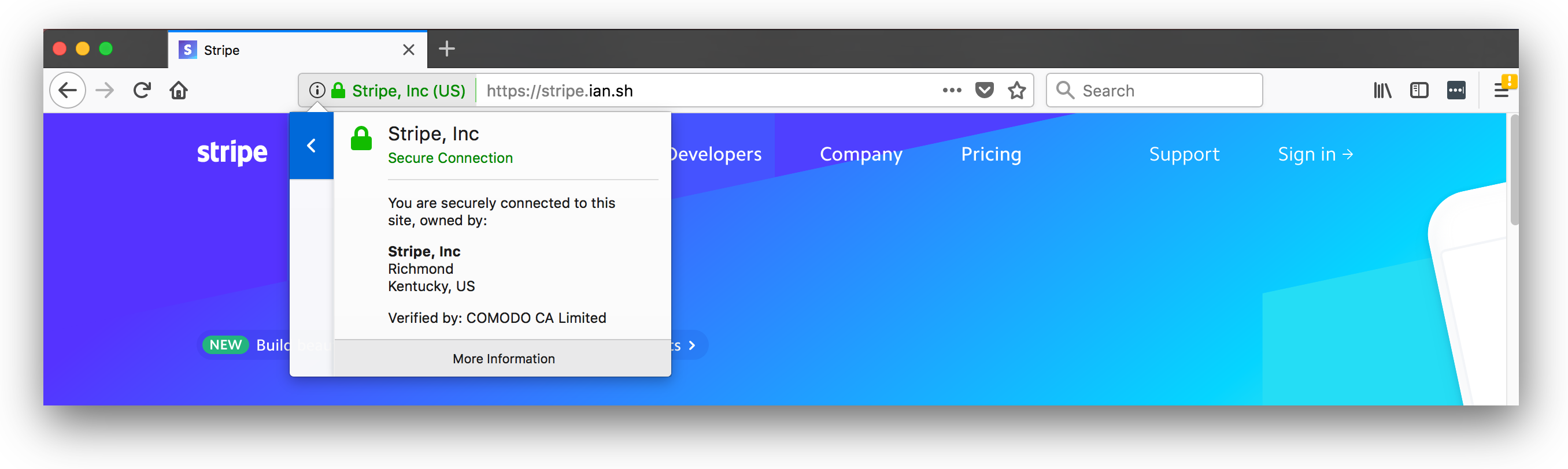

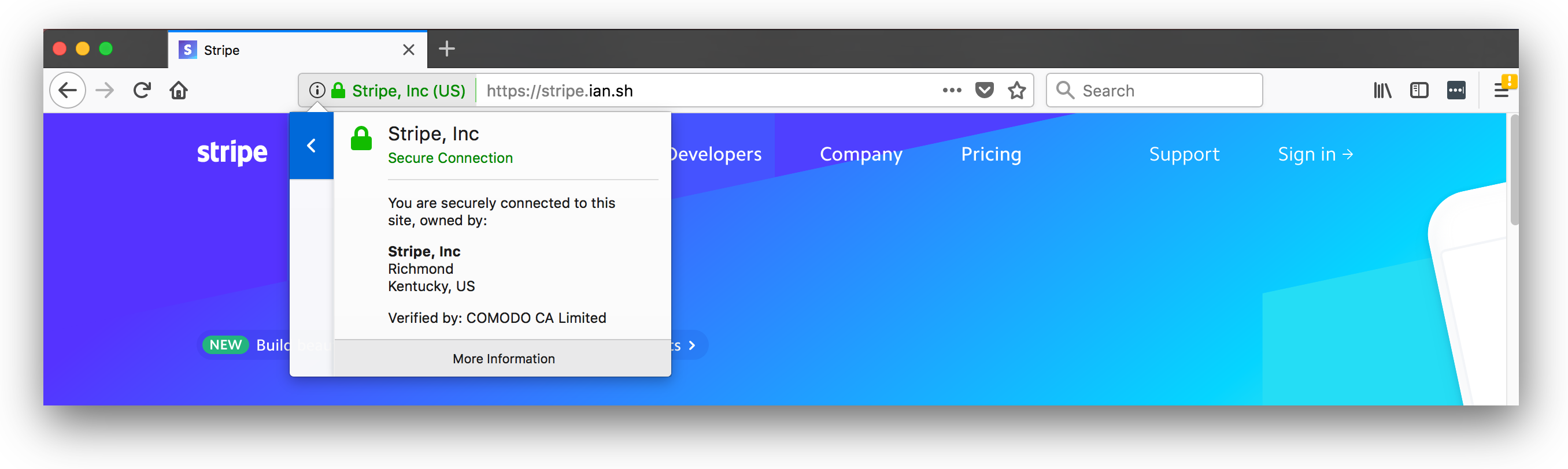

Today I will demonstrate another problem with EV certificates: duplicate company names . In particular, this site uses an EV certificate for Stripe, Inc., which was legally issued by Comodo. However, when you hear “Stripe, Inc.,” you are probably thinking of a payment system registered in the state of Delaware . However, on this site, you interact with Stripe, Inc., registered in Kentucky . This problem can also occur for companies with the same name in different countries.

How can a user determine which site he works with? Browsers hide this information, at best show the country of registration. Obviously, here and the real and fake Stripe are in the same country. With enough mouse clicks, you can open the system certificate viewer or force your browser to show you the city and state. But all this does not help ordinary users, and they, most likely, will just blindly trust in a bright green indicator.

')

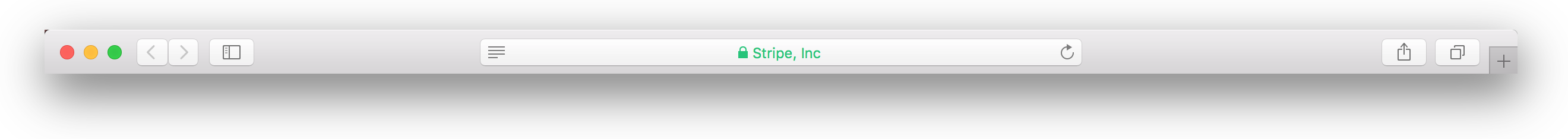

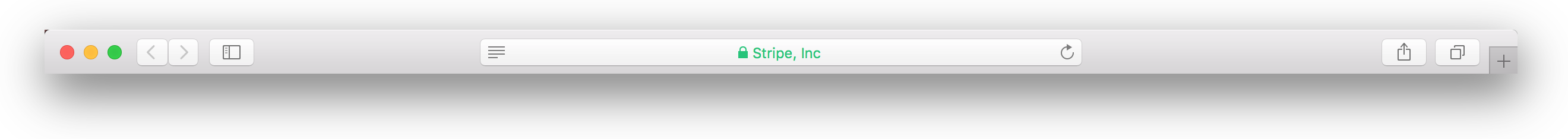

Let's look at browser user interfaces. In Safari, the URL is completely hidden ! This means that the attacker does not even need to register a similar domain for phishing. You can register any domain, and Safari will be happy to display it with a beautiful green indicator. Below is a screen shot of this site. Hard to believe, yes?

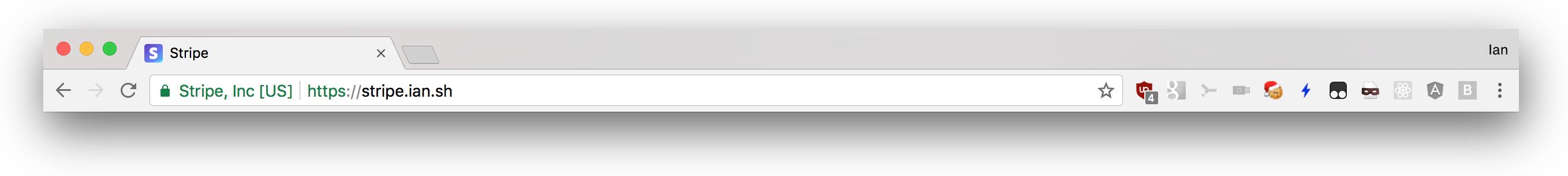

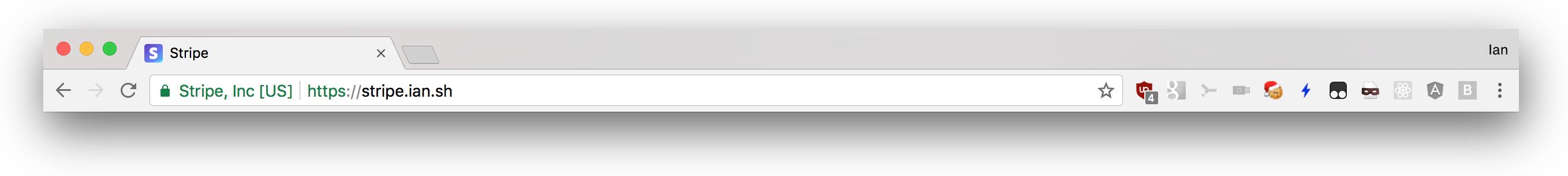

With Chrome, the story is a little better, but only if you bother to see the full URL. Chrome does not have its own way to view anything other than the name of the company and the country of the certificate. New versions of Chrome will open the system certificate viewer with two clicks of the mouse (in older versions, viewing the certificate is completely removed (this is not quite the case - approx. Transl.) ), But the system certificate viewer is useless for any ordinary user.

Firefox behaves similarly to Chrome, but allows users to view the city and registry state with two mouse clicks. It is still meaningless; even if ordinary users bother to check it, they still need to know where the company is located, in which they place an order, and make sure that they are in compliance.

One of the questions may be how practical this attack is for a real attacker who wants to get someone's data by phishing. Firstly, from registering a legal entity to issuing an EV certificate, I spent less than an hour of my time and about $ 177. $ 100 is a company registration, and a certificate is $ 77. From the time of registration until the issuance of the certificate, it took about 48 hours.

The main advantage of EV certificates, on which the proponents of extended verification are focused, is that obtaining EV certificates leaves behind a chain of paper traces leading to the identity of the attacker. However, in this process identity verification is minimal. Dun & Bradstreet was the only organization that tried to verify my identity and made it a few trivial questions. Buying a certificate and answering common test questions are neither difficult nor costly.

Attempts to verify the identity of the state of Kentucky or the agent I used in this process were not. This is typical when registering a company in the United States. Thus, attackers can easily obtain EV certificates. Some attackers may make more effort, for example, send phishing SMS messages. Mobile Safari on iOS will hide the URL after it is opened and significantly increase the likelihood of success in collecting credentials. And, of course, there is no way to view the certificate using Mobile Safari.

After James Burton received the “Identity Verified” certificate, a discussion followed the public CA / Browser Forum mailing list, cabfpub . Some ideas were rejected, mainly focused around adding a stronger binding to the person requesting the certificate to discourage criminals from obtaining these certificates. Nevertheless, it is hoped that all these “crutches” may stop criminals who wish to receive an extended verification certificate.

One of the proposed solutions was to require applicants of some form of personal verification, whether virtual or in real life, and to require the provision of identification information to confirm their identity. Although this may prevent some intruders, those who are engaged in more targeted or loud attacks will not have problems to spend a little time for falsifying identification documents or try to circumvent other verification methods.

It is worth noting that the Basic Requirements - a set of standards that trusted certificates must meet - include the High Risk Certificate Requests. However, the definition of the term Request for a High Risk Certificate is not very clearly formulated and in some sense useless. The query “may include names with increased risk for phishing,” but the definition function is delegated to certification authorities, which must keep the list of phishing targets up to date.

There are no doubt many solutions to this problem. But ultimately, any method based on the fact that the name of the legal entity is shown to users is completely flawed. Due to the fact that EV certificates work this way, browsers do not have special opportunities to fix the problem. However, they can take steps to ensure that EV certificates do not replace other important parts of the user interface, as Safari does.

As a rule, this process works quite well, and erroneously issued certificates are few. However, the problems are more than enough. EV certificates contain information about the legal entity behind the certificate, but no more. The name of the legal entity, however, may be quite variable; For example, James Burton recently received an EV certificate for his company “Identity Verified” (English Authenticity Verified - approx. Transl.) . Unfortunately, users simply do not have the opportunity to see and understand such features, and this creates considerable scope for phishing.

Today I will demonstrate another problem with EV certificates: duplicate company names . In particular, this site uses an EV certificate for Stripe, Inc., which was legally issued by Comodo. However, when you hear “Stripe, Inc.,” you are probably thinking of a payment system registered in the state of Delaware . However, on this site, you interact with Stripe, Inc., registered in Kentucky . This problem can also occur for companies with the same name in different countries.

How can a user determine which site he works with? Browsers hide this information, at best show the country of registration. Obviously, here and the real and fake Stripe are in the same country. With enough mouse clicks, you can open the system certificate viewer or force your browser to show you the city and state. But all this does not help ordinary users, and they, most likely, will just blindly trust in a bright green indicator.

')

Let's look at browser user interfaces. In Safari, the URL is completely hidden ! This means that the attacker does not even need to register a similar domain for phishing. You can register any domain, and Safari will be happy to display it with a beautiful green indicator. Below is a screen shot of this site. Hard to believe, yes?

With Chrome, the story is a little better, but only if you bother to see the full URL. Chrome does not have its own way to view anything other than the name of the company and the country of the certificate. New versions of Chrome will open the system certificate viewer with two clicks of the mouse (in older versions, viewing the certificate is completely removed (this is not quite the case - approx. Transl.) ), But the system certificate viewer is useless for any ordinary user.

Firefox behaves similarly to Chrome, but allows users to view the city and registry state with two mouse clicks. It is still meaningless; even if ordinary users bother to check it, they still need to know where the company is located, in which they place an order, and make sure that they are in compliance.

One of the questions may be how practical this attack is for a real attacker who wants to get someone's data by phishing. Firstly, from registering a legal entity to issuing an EV certificate, I spent less than an hour of my time and about $ 177. $ 100 is a company registration, and a certificate is $ 77. From the time of registration until the issuance of the certificate, it took about 48 hours.

The main advantage of EV certificates, on which the proponents of extended verification are focused, is that obtaining EV certificates leaves behind a chain of paper traces leading to the identity of the attacker. However, in this process identity verification is minimal. Dun & Bradstreet was the only organization that tried to verify my identity and made it a few trivial questions. Buying a certificate and answering common test questions are neither difficult nor costly.

Attempts to verify the identity of the state of Kentucky or the agent I used in this process were not. This is typical when registering a company in the United States. Thus, attackers can easily obtain EV certificates. Some attackers may make more effort, for example, send phishing SMS messages. Mobile Safari on iOS will hide the URL after it is opened and significantly increase the likelihood of success in collecting credentials. And, of course, there is no way to view the certificate using Mobile Safari.

After James Burton received the “Identity Verified” certificate, a discussion followed the public CA / Browser Forum mailing list, cabfpub . Some ideas were rejected, mainly focused around adding a stronger binding to the person requesting the certificate to discourage criminals from obtaining these certificates. Nevertheless, it is hoped that all these “crutches” may stop criminals who wish to receive an extended verification certificate.

One of the proposed solutions was to require applicants of some form of personal verification, whether virtual or in real life, and to require the provision of identification information to confirm their identity. Although this may prevent some intruders, those who are engaged in more targeted or loud attacks will not have problems to spend a little time for falsifying identification documents or try to circumvent other verification methods.

It is worth noting that the Basic Requirements - a set of standards that trusted certificates must meet - include the High Risk Certificate Requests. However, the definition of the term Request for a High Risk Certificate is not very clearly formulated and in some sense useless. The query “may include names with increased risk for phishing,” but the definition function is delegated to certification authorities, which must keep the list of phishing targets up to date.

There are no doubt many solutions to this problem. But ultimately, any method based on the fact that the name of the legal entity is shown to users is completely flawed. Due to the fact that EV certificates work this way, browsers do not have special opportunities to fix the problem. However, they can take steps to ensure that EV certificates do not replace other important parts of the user interface, as Safari does.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/344516/

All Articles