Technical diary: half a year developing mobile PvP

In March 2017, we assembled a small team and set about developing a new promising project. Without much detail I can say that the task was interesting and seductive - mobile, synchronous, command PvP. After 7 months of active development, I wanted to tell my colleagues from other projects and departments of Pixonic the technical details and I prepared a presentation for them, which later turned into this article.

As a team leader, I will tell you what problems and problems we had to face, how to solve them and why. We use the iterative approach of adding functionality to the project and at the moment we have implemented: PvP on iOS and Android (both platforms play on the same servers); character set, three dozen game mechanics, bots; matchmaking; a set of meta-features (customization of characters, pumping, and others); Solved the problem of scalability for the whole world.

')

So let's go.

Disclaimer

But I must immediately make a reservation that the solutions described in the article are already historical phenomena and facts, made up of many circumstances: business and game design requirements for the product, deadlines set, the potential of the team and the uncertainty of some problems at the start. This is not the best practice, but an experience that is never superfluous.

Hurts (,) fun

Even before the development, we already had some difficulties that we definitely have to face. Namely:

- Synchronous PvP . It is never easy, you have to choose and implement a whole set of technologies, in any of which your team may not have experience. There are a large number of combinations of technologies in order to solve problems: smooth images, hiding delay, cheating, simulation performance (server or master client), MTU problem and traffic cost problem. Message delivery lag is not canceled, while messages must be delivered as quickly as possible and their delivery should not depend on each other. For these reasons, we could not use the TCP protocol, and using UDP adds a set of cases that also need to be processed.

- Mobile platforms . Additional work on performance and limitations (example: maximum use of RAM). You also need to keep in mind that you will always have players with unstable Internet and bad ping - they can not be ignored.

- Accessibility from anywhere in the world . Ideally, the player should not bother with the choice of server, the application should automatically understand the location of the device and find the optimal connection point.

- The specifics of the genre . Morally, we were ready, that there would necessarily be mechanics that no one else had yet implemented (especially those projected onto our technical limitations) and we would have to become a pioneer complete with all the cones.

- The width of the technology stack . Looking at the functional requirements, we can say for sure that in one project at least 3 subprojects are combined: a game client, a game server and a set of meta-micro services. It turned out to be a difficult task to synchronize a command for synchronous release of features. Separately, there was a problem, how to store the code, how to fumble and reuse it.

Then I tried to describe our situation in the form of “problem - solution”.

Code storage and sharing

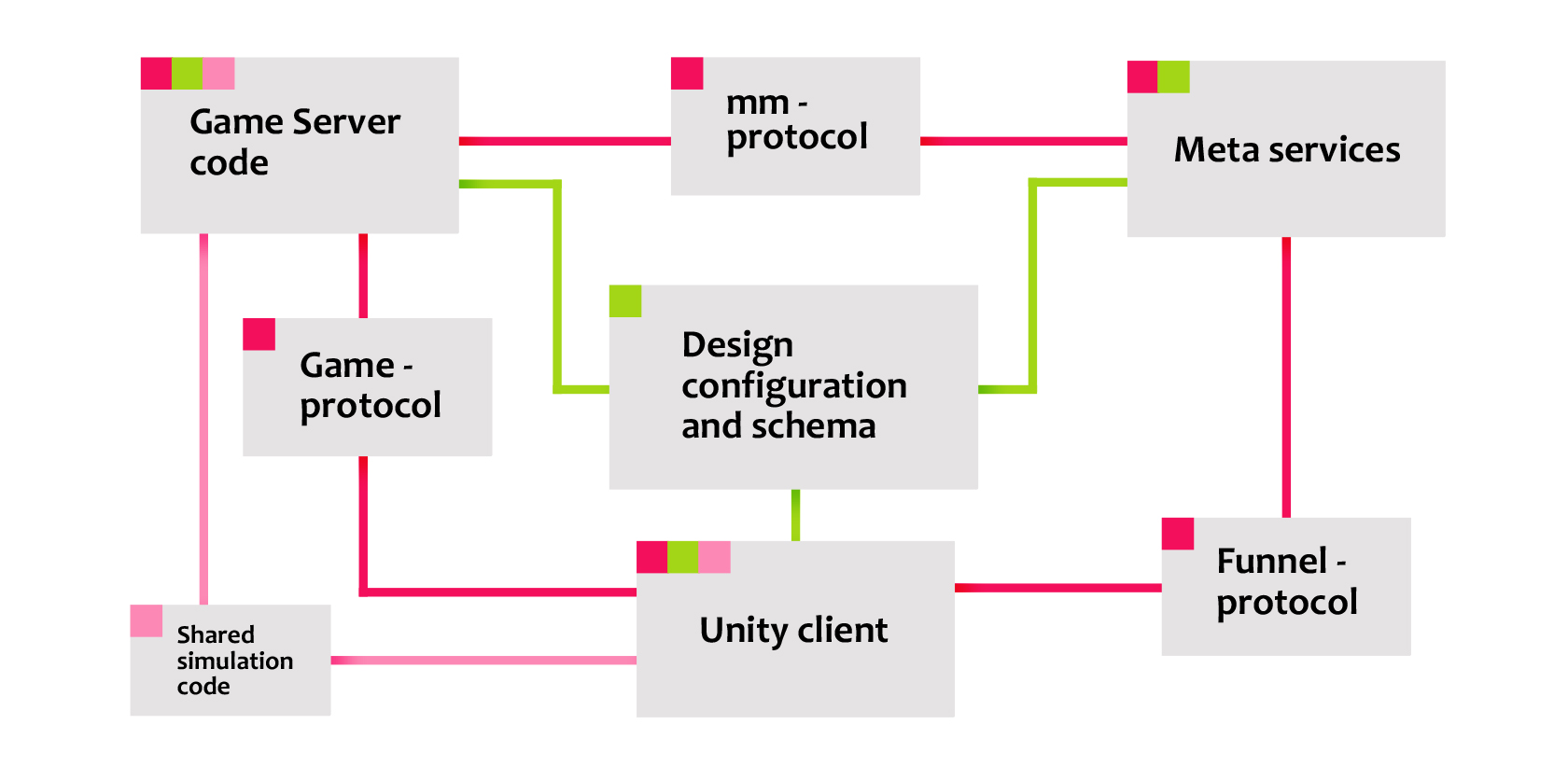

As already mentioned, the project consists of three subprojects:

- Unity client;

- Windows game server using Photon transport (not PUN);

- set of services for meta games (java).

I figured that in storing them all in one git repository there are more minuses than advantages, since all CI processes become more expensive and take longer. As a result, we have three repositories.

We use protocol buffers to exchange messages between all three subprojects. From this it follows that we have somewhere to store the .proto files and the generated code files for these messages (by the way, committing the generated files is not a very good tone, but for Unity this reduces the number of compilations when opened, which saves time). Moreover, they must be different for different protocols, there is no point in reusing packets, since the server and client need different arguments. There was a task how these files to receive to all projects. We solved it with git submodules. Between each of the 3 pairs of major projects, we started up an additional repository and added them as submodules to the main projects. Now there are six repositories.

To speed up the debugging of the simulation and the ability to run the game simulation without being tied to the server, we have separated the simulation code. This gave us a lot of opportunities - profiling the launch of hundreds of games as a console application with time acceleration, or, for example, using simulation in the Unity client for the local work of combat training. For the production itself, it is also very convenient: the programmer, creating a new gaming feature, can play Unity right away, he doesn't even need to deploy a local server. So that the simulation code could be located both in the client and in the game server, it also had to be rendered into a separate submodule.

After some time, we needed to store and track changes to game configs, the necessary parts of which later diverged from subprojects, and we made a separate submodule containing a proto-scheme for its deserialization.

I already told about pluses, now about minuses:

- I had to train the team to work with submodules, many had no experience with them.

- You need to support a single authentication option in git. For example, to build a client in teamcity, I want to download a client repository with submodules via ssh. But in the counterexample, it is very wasteful to work with personnel (for example, artists), who has little experience with git, explaining to them what public and private keys are. As a result, this problem was “resolved” by registering the modules in .gitmodules via relative links:

[submodule "Assets/shared-code"] path = Assets/shared-code url = ../shared-code.git

But it’s not a fact that the SourceTree of your version will be able to understand this, and you will have to keep all repos on one host of the gita. - It may be worth merging the protocol repositories into one and set up stripping when building the client to reduce the number of sub modules and the total number of operations with git, but this may cause other difficulties, since all 3 subproject commands will commit changes there.

- Another important disadvantage is that if you are working on git-flow, then you will have to maintain feature branches in all affected repositories, otherwise technical debt of deep-level modules integration will accumulate in the top-level repo.

Example: a programmer makes a feature in his main repo branch and in a submodule feature branch, and at this time, a new functionality is poured into the develop submodule branch, which will not allow you to simply upgrade to the latest version. It is necessary to change the code of the main module to support these changes. As a result, the programmer will not be able to pour his finished feature into develop until he writes an adaptation to the latest version of the submodule, which is often not connected with his features. This slowed down the integration and once again switched programmers from the contexts of their tasks. As mentioned above, you first have to write changes to the submodule in the feature branch, then write the adaptation of the main repository in the branch of this feature too, and only after that, having passed reviews and tests, these branches merge simultaneously in develop their repositories.

Loss of player input

We now turn to the problem is much more closely related directly to the product. Let me remind you that we use non-reliable UDP between the game server and the mobile client, which does not guarantee the delivery of messages or the correctness of their order. This, of course, imposes a number of problems that are critical for the player himself. A good example is an expensive, powerful rocket and a button to launch it. The player waits for a suitable situation to use this ability and presses the button 1 time, at the most favorable, in his opinion, time. We have to deliver this information to the server as quickly and as quickly as possible so that the player does not have time to pass this moment. But if this package is lost or comes in 2 seconds, then our goal is not achieved.

First, we considered the strategy of data re-sending in the absence of confirmation of acceptance, but we wanted to maximize the loss of time to the period of sending customer data. An additional task was to make the button of the shot pressed during stunning work after the character exited from stunning in the simulation on the server.

The solution turned out to be inexpensive, but effective:

- Every frame of the client’s work, we record the input and number it.

- We store them in the collection on the client and send several last entries to the server at once (for example, the last ten). The size of such messages is very small (on average from the client - about 60 bytes) and we can afford it.

- The server receives messages, takes only the part that it has not received yet, and adds them to processing. Thus, if any packet from the client to the server does not reach, any next packet that arrives will always contain all the latest input history.

- For solving the problem of deferred use of skill when a character is ready (leaving the camp) and so all the data is there. The processing logic knows which input frame was processed for a specific player, and in certain gameplay situations it will continue to process it as soon as possible. The advantage of our approach in this case will be that we will rarely miss the “holes” in the input queue.

The problem of smoothness of the image on the client

Using non-guaranteed delivery methods, we also face the problem of getting the state of the world back from the server to the client. But more on that later. To begin with, I would like to describe the obligatory problem that the team of any game project transmitting states over the network solves.

Imagine a game server is an application that does the same thing a certain number of times per second: it receives input over the network, makes decisions, and sends the status back through the network. Now imagine a client is an application that (among other things) displays the game state for a certain number of frames per second (for example, 60). If you simply allow to display what came from the network, then every 2-3 frames the client will display the same incoming state, and the display will be jerky, and in the case of uneven delivery, also with time acceleration / deceleration. In order to make the display smooth, it is necessary to use interpolation between the two states from the server and display the calculated intermediate values over several necessary frames.

Leaving the client in the past ...

But we have only one state for this moment and no second to draw intermediate frames. What to do? Solution: we shift the time of the client's events a bit into the past so that at the time of rendering we already have a theoretical opportunity for the next state of the world to come.

In practice, this is not so rosy: UDP does not guarantee delivery, and if the state of the world does not come to the client, then you will not have data for several frames to display - you will receive the so-called "frieze". Balancing between the input lag and the percentage of packet loss, we use a departure into the past by 2 sending periods + half RTT. Thus, even if one packet is lost, you will have time to receive the next one. At the same time, if the reception of packets was interrupted for 2 or more periods, then it is very likely that further disconnection will occur, which is much clearer for the player than spontaneous lags. The player will see the reconnect window and it will not spoil the gaming experience so much.

The problem of non-permanent ping

In practice, a circuit with interpolation and going back does not always work well. A player could start a game by playing Wi-Fi at home with a ping of 10 ms, and then go outside, take a taxi and ride around the city with pinging mobile Internet turned on for 100 ms. In this case, remembering at the start of the game RTT, the player may constantly not have enough time to interpolate, even if the packages will be delivered perfectly, evenly and without loss.

In our case, we solved this problem as follows:

- Each time we analyze the time of arrival of the package and what time the server implies.

- If the state of the network has deteriorated, then we smoothly move into a bigger past, exactly on the reserve we need, in order to maintain the rule:

2 * Send Rate + RTT/2 - On the client, the input lag will increase, but the picture remains smooth.

Visually, the problem remains that when we discovered this, the client had already started to lag. We move it into the past not instantly, but for a short time (0.5 seconds), in this case it will not have data for 1-2 frames of data. In case of ping drops by more than 1 Send Rate, the player will notice a small (1 \ 30 second) one-time jerk.

Similarly, in the opposite direction, if the ping is reduced, the client determines this and brings the display closer to the present in order to achieve the optimal balance between a smooth picture and the lowest input delay.

Answers on questions

I would like in conclusion to answer a few questions that you might have.

Why, instead of dealing with input lag, we do not predict client behavior in the simulation locally?

This decision comes from the genre and mechanic of the game: if you make a first-person shooter, with instantaneous phenomena and the absence of undoing player influences, then local prediction + lag compensation is perfect for you. In case your gameplay involves a large number of frosts, shots and other mechanics that affect players and change their behavior, then the manifestation of network artifacts will approach 100%. The most desperate in this regard, I believe the team of the project Overwatch from Blizzard, who found the best balance between minimal artifacts and the need for local prediction. But this is on the PC, where the average ping of players theoretically allows it. In our case, for a local player in 100% of cases, the dash forward would end with a “teleport” to its original state with any stunning.

How will players from different countries play with different ping?

Who has better ping will naturally have an advantage, as he has more time to react. Example: an opponent wants to throw a projectile at a player. A player with a smaller ping will notice the beginning of the enemy's animation a little earlier and he will have more chances to perform a protective action. Moreover, the protective action will reach the server faster and the probability of time to evade will increase.

Who will be the first to shoot if both are pressed simultaneously and the ping of one player is greater?

The server does not take into account the time of pressing, only the arrival time of the input and its order, so that the principle of the answer above works.

One more thing

I hope that the material I have written will be useful to other developers who are embarking on a similar path. In general, there are so many problems and solutions that have been accumulated during this time of working on a project that they will suffice for more than one article.

Good luck!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/343820/

All Articles