Subject-oriented languages for business applications - user interfaces

This article is a translation of the Modeling User Interfaces article.

Development of business applications is related to solving problems in various subject areas, such as data storage, business logic processing, user interface design. To increase productivity and quality, not a single domain-specific language (DSL) is enough, not a few if they are not sufficiently integrated with each other. Significant improvements can only bring a holistic approach, in which several DSLs are used consistently to simulate solutions in different subject areas.

In this article, we will look at an example of DSL, with which we model standardized user interfaces for our business applications in modellwerkstatt.org . The logic inherent in DSL allows you to visualize object graphs completely and in a very simple, declarative form. We show how easy it is to embed regular Java code with which you can interact, which provides additional flexibility and security, in particular type safety. Pointing to the distinction between internal and external DSL, we will go to the JetBrains MPS and immediately consider our DSL for user interfaces. Finally, we present a number of general considerations regarding the interaction of DSL with each other and their extensions.

Domain-specific languages are widely used in modern software development. They can be given the following definition: “programming languages that bring the level of abstraction beyond programming, defining a solution that directly uses concepts and rules from a specific subject area”. (Kelly and Tolvanen, 2008). Although general purpose languages (General Purpose Language, GPL), such as Java or Kotlin, are widely used in a wide variety of subject areas, domain-specific languages are adapted to a specific subject area, which ensures their extremely high efficiency in this area. Such languages provide abstractions adequate to the problem being solved and allow expressing solutions briefly and succinctly, and the use of such solutions often does not require the qualification of a programmer.

')

As an example, DSL is often given the query language SQL. SQL allows users to process data, tables, and databases without any programming skills. SQL provides a high level of abstraction due to specific concepts, such as “sampling” or “updating”, in the subject area “data in rows and columns”. The SQL language is clear and expressive, but it also links the user to one particular subject area. DSLs such as CSS, regular expressions and XPath are also well known. In addition to these “universal” DSLs, a number of highly specialized DSLs have been created that are used in individual organizations for capturing subject knowledge and automated generation of uniform code in general-purpose languages.

The so-called internal DSLs based on the base GPL are widespread. “Internal DSL is a special form of API in a basic, general purpose language, often also called a fluid interface” (Fowler, 2010). Internal DSL defines the concepts and operations that exist only in a specific subject area, and helps to work in this particular area. Well-known examples of internal DSL, built on Java - JMock and JooQ. However, internal DSL has significant limitations. The syntax of the internal DSL cannot violate the syntax of the basic general purpose language. Otherwise, the base language compiler would not be able to parse the resulting code and compile it. In addition, support for syntax highlighting, autocompletion, and type checking in IDEs is also limited to DSL and depends on the underlying GPL. From this it follows that, firstly, internal DSLs can be useful only to developers owning the GPL, and secondly, severe restrictions are imposed on the syntax and visual presentation.

SQL can be considered an external DSL, since it is not embedded in any other GPL and is not based on it. SQL provides its own keywords, operations, and syntax. It was conceived out of any (syntactic) connection with general purpose languages - it is completely independent. External DSLs can be optimized to ensure full coverage of information in the subject area and maximum expressiveness without any limitations on readability and clarity. The visual presentation, aesthetics and ergonomics of an external DSL can be developed to meet the requirements of not only developers, but, perhaps, the actual domain specialists themselves. Only in this case, improvements are possible in terms of formulating, communicating and understanding solutions in a particular subject area. It was these considerations that initially pushed for the creation of domain-specific languages.

However, external DSLs have a number of drawbacks. Firstly, since such a language is not based on a general-purpose language, the IDE is initially absent for it. This is especially true in cases where DSL is aimed at a very narrow subject area, that is, if the potential number of users of the language does not justify the effort required to create language tools or a full-fledged IDE. At the same time, DSL users still need intelligent tools to assist in the work and increase productivity. Second, and more importantly, external DSLs do not provide a simple way to access external artifacts, such as code in a general-purpose language or declarations stored as XML. The external DSL remains, in a sense, isolated until additional import and export facilities (generators that produce executable code in a general-purpose language) are developed. In practice, interfacing with a complete development environment is extremely important because DSL alone does not cover all aspects of a software solution. This is where language development tools can help.

JetBrains MPS is a language development tool that allows you to define, reuse and compose domain-specific languages and provides additional tools for these languages.

Unlike other development environments, MPS provides the broadest support tools, without relying on parsers. Usually, tools and compilers get an abstract syntax tree (ASD), parsing a textual representation of a code with a fairly specific grammar. In the future, using this structured tree, the transmitted information is converted into executable code.

In contrast to this approach, in MPS, the manipulation of the SDA is performed directly, using a projection editor. Although the projection editor is similar to a text editor, the user edits the tree structure in real time. Text is not used to store the code - the ASD itself is saved, which eliminates the need for syntactic analysis. Consequently, syntactic ambiguity is eliminated, and semicolons or brackets are not required to distinguish concepts. The projection editor ensures the brevity and adequacy of the visual representation of the subject area. Code completion and error control are easily implemented through examining and bypassing the ASD - all this is supported in the IDE MPS without any extra tweaks. In short, MPS provides instrumental support for domain-specific languages in general, eliminating the need to implement it separately for each language.

The use of SDA as the basis of MPS gives an important advantage. Since the ambiguity of grammar is eliminated, languages can be combined by any means. Existing languages can be expanded and enriched with new concepts. Languages can complement each other, inherit functionality and features. This allows you to easily reuse existing language concepts, which speeds up development and contributes to a unified approach.

To illustrate these considerations from a practical point of view, we turn to our example.

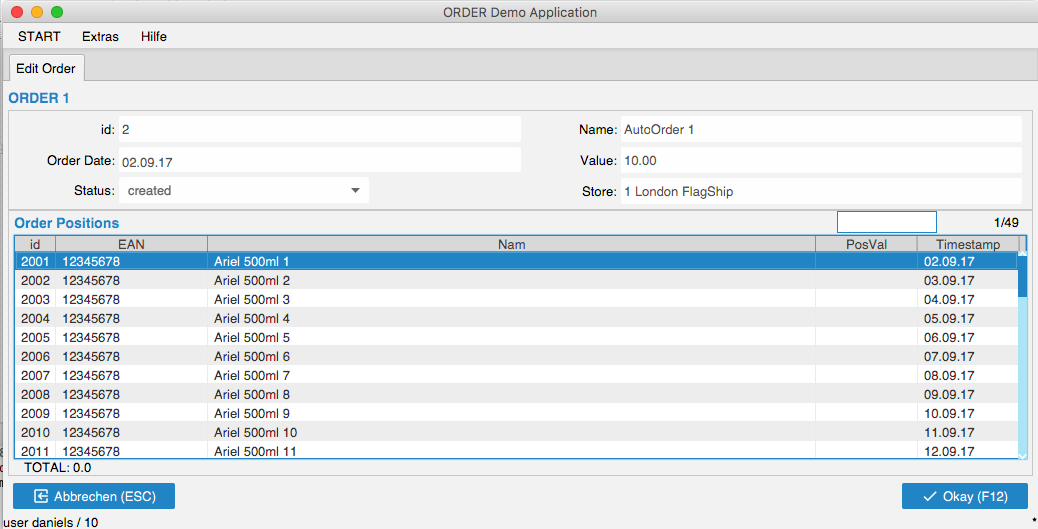

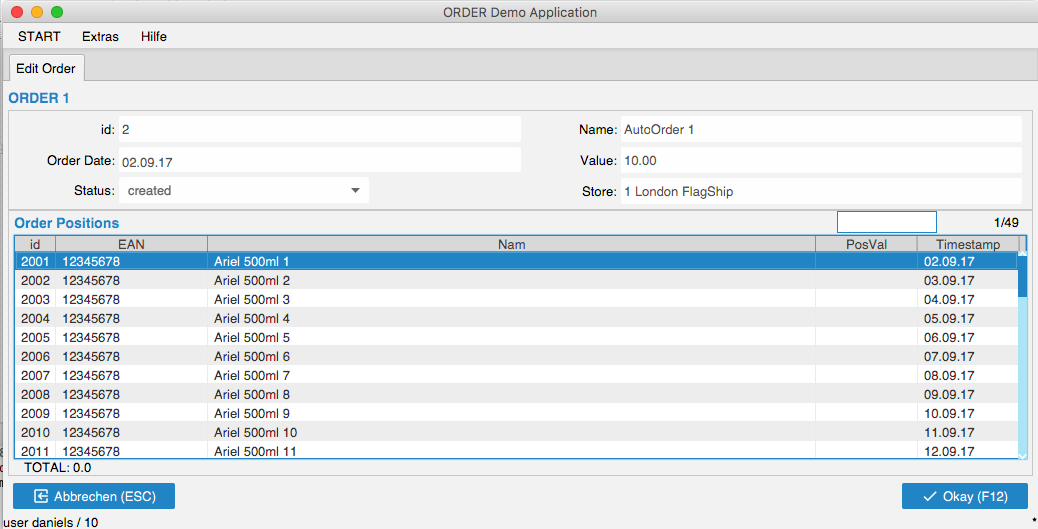

DataUx successfully demonstrates the idea of combining languages. We have created this language specifically for the specification of user interfaces of Java applications designed for intensive data processing — usually business applications, for example, for managing invoices for payment or for monitoring stockpiles. DataUx provides various language concepts that allow you to define data entry forms, tables for visualizing collections, and layouts. In DataUx, user interface elements are supplied with actual data values through an extended property binding. Java objects with component properties (recipients and installers for specific identifiers) are organized into an object graph. Then - and this, in our opinion, is very unusual - the whole graph is tied to the user interface. In this simple example, an order object with various properties also contains a list of order items (OrderPosition). The following screen capture shows the user interface for the Order object with its properties and order items. The second screenshot shows the specification of this user interface itself using DataUx.

Screenshot 1: Demo application user interface with one Order object containing several OrderPosition objects

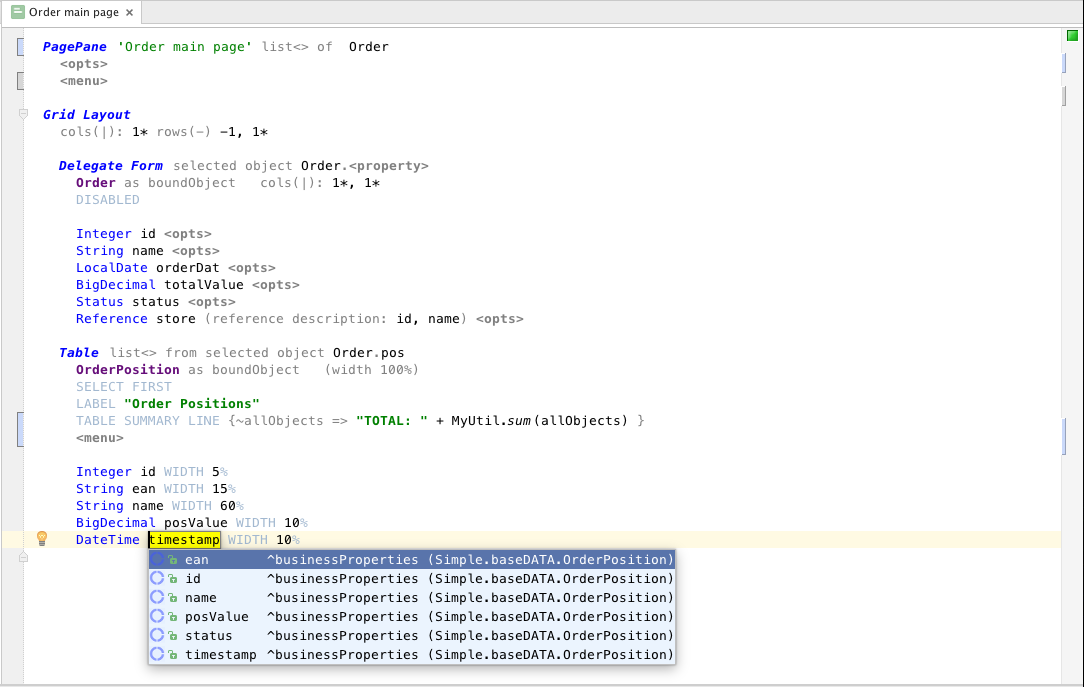

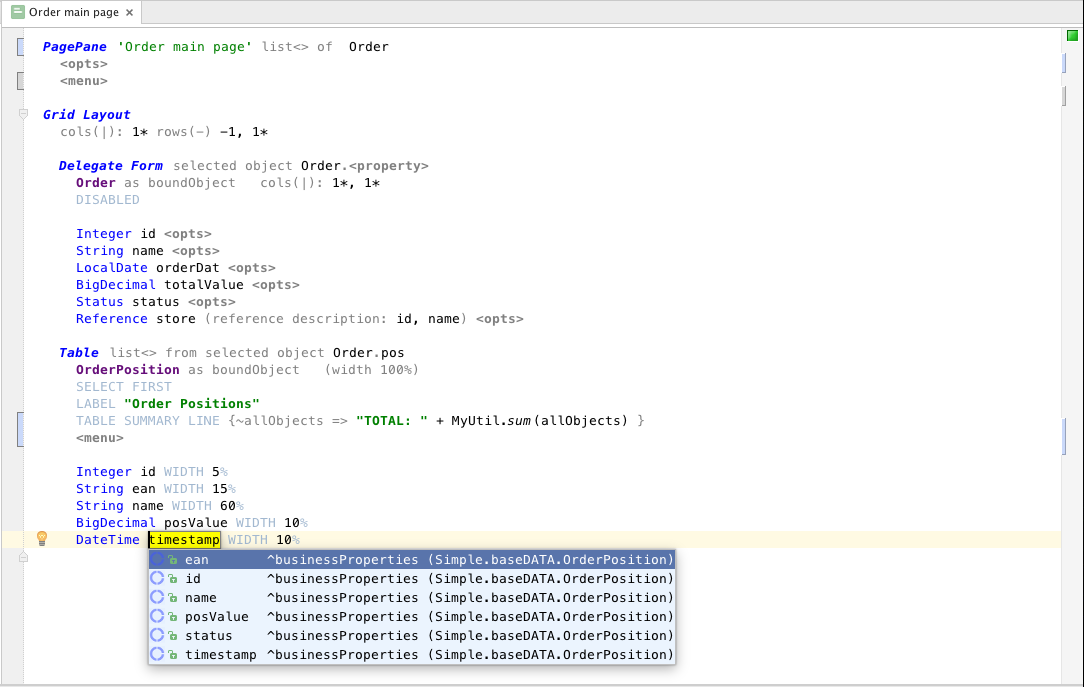

Screenshot 2: Order user interface specification for a DataUx demo application in MPS

Above, in screenshot 2, the “main order page” is shown, tied to the list of Order objects. In the grid layout consisting of a single column (1 * = maximization with a weighting factor of 1), we placed two user interface elements in two lines, the first one is minimized as far as possible (-1), and the second is maximized again (1 *). On the “Delegate Form” form, the values of the six properties of the Order object are shown in two columns; the table displays a list of items for this order. The DISABLED keyword puts the entire form into read-only mode; the table and without additional configuration is available only for reading by default.

The main idea of the DataUx language is based on the binding of components and on the “master data - details” template. Each PagePane panel is able to visualize a graph consisting of objects, in which for each type of object there is a “selected object”. In our example, there are two types of objects: Order and OrderPosition. Thus, two current choices are essential: the selected order and the selected order item. In order for the currently selected object of a certain type to be loaded into the user interface element, each interface element must be tied to the corresponding object type. In separate elements of the user interface, you can access the properties of objects and bind them.

The “Delegate Form” form is tied to the order currently selected, and the table is tied to the list of positions of the selected order (recorded as Order.pos). Consequently, the “Delegate Form” can visualize the properties of the Order object, while the table can visualize the properties of OrderPosition objects in its columns. For OrderPosition, five properties are declared and the width of the corresponding columns is set.

As part of our “selected object” logic, the table is used not only to display lists of objects, but also to determine the selected object. The selected table row directly corresponds to the “selected object” of this type. In our example, when you select another row in the table, you select and define an object of type OrderPosition. Thus, the user interface was improved by visualizing the details of the order item (its properties) in another form, tied directly to the OrderPosition object.

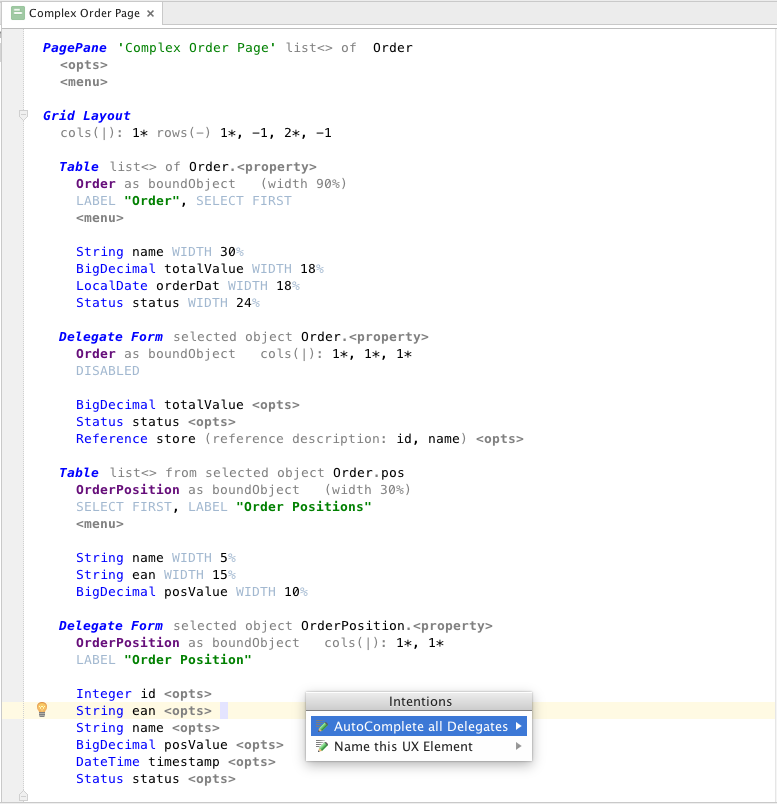

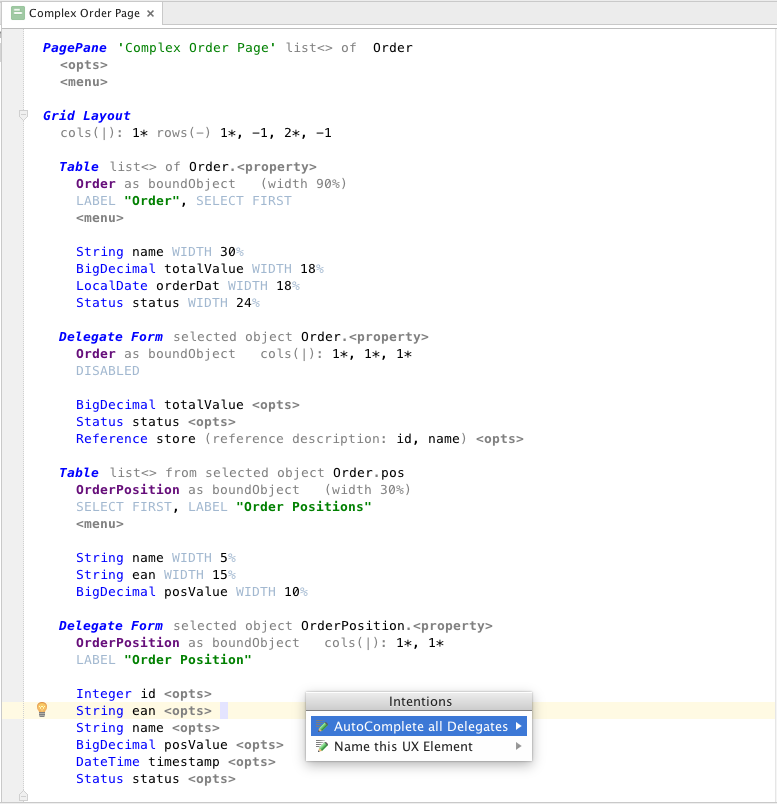

The “order main page” from the second screenshot by type is a list of Order objects; however, if only one order is transferred, it automatically becomes the selected object of this type. This is a feature of our PagePane concept. If several orders were submitted to the page, an additional table would be required to determine the selected order. Only this would allow to realize the selected order, which is necessary for the detailed data form and the OrderPosition table. The third screen shot shows a more complex case involving multiple orders. As already mentioned, we have added a detailed form to display the properties of the selected order item (OrderPosition object).

Screenshot 3: A more sophisticated user interface for a demo application with master data – detailed data relationships

Continuing to follow this object anchoring logic, using DataUx it is not difficult to define user interfaces for complex object graphs. A user binds UI elements to an object type to access specific properties of this object. During execution, the currently selected object of the corresponding type is loaded into the user interface element. This is probably the most difficult point to understand in the DataUx language. However, this object binding logic is checked by the DataUx type system and a whole range of consistency checks. For intelligent editing, context-sensitive auto-completion is provided, and even "auto-completion of user interface elements".

In the context of the discussion of domain-specific languages, the relationship between DataUx and Java is noteworthy. Obviously, while DataUx is not compatible with Java syntax, it relies on Java concepts such as properties and classes. There are even Java type-based type checking rules. Moreover, external Java artifacts are mentioned among the user interface elements. How is this achieved?

JetBrains MPS comes with a full-featured Java implementation. Implementing this GPL in MPS is no different than implementing any specialized DSL. There is a good projection editor that reproduces the usual model of working with an intelligent text editor Java - supports the definition of classes and interfaces, their members, and of course, expressions. Since MPS also has a jar import tool, it can be used as a standalone full-featured Java IDE. We have expanded and expanded this Java implementation with the DataUx language. As a result, it became possible to use powerful Java concepts, especially expressions and types. Thus, DataUx received basic programming support without any additional effort.

By specifying user interface elements in the DataUx language, users can refer to declared Java objects and their properties if they are loaded into the IDE and are available in it. Intelligent access areas for class references, properties, and selections are calculated during editing. As can be seen in Figure 2, the DataUx “Table Summary Line” parameter provides a concept similar to closures with the variable “allObjects” (type - list). In the right-hand side, a Java expression is returned that returns a string (type is Java.lang.String). The example calls the static sum () method of the class MyUtil. It should be noted that in the context of this parameter, any valid Java expression can appear - from method calls to string concatenation and references to Java variables. Intelligent access areas for all links are calculated in the context of the parameter. Type checking is performed for all expressions.

The DataUx language makes full use of all existing concepts of the MPS Java language, in particular, expressions and type system processing — these elements of the language are usually extremely complex. The use of Java expressions in DataUx, despite its simplicity, gives the user additional benefits. Expressions allow you to flexibly adapt to the requirements of a specific case, without resorting to any external, non-integrated program code. The key advantage is also provided by the ability to extend other languages: while maintaining independence from the syntax of the MPS Java language, you can easily refer to concepts that are declared in this language, for example, the static method that is called in the Table Summary Line parameter.

DataUx language was developed for one of our large customers - retailers from Australia. On the customer side, eight developers implement all the necessary user interfaces on DataUx, without affecting any additional aspects of the user interface in plain Java code. After successfully defining the idea and structure of the language, the language itself was developed in a couple of days. However, the development of the user interface runtime took longer due to the complexity of implementation under several different technologies.

DataUx language is available on GitHub.

DataUx is a very simple and logical domain-oriented language that allows you to delegate the development of user interfaces to people without programming skills. The steepness of the learning curve is so small that almost no explanation is required. This language also makes it extremely easy to understand and maintain existing user interfaces. Moreover, the user interface specified with DataUx does not depend on the implementation technology. This is a very important advantage, as user interface technologies are changing rapidly today. Note that we already provide DataUx runtime for Apache Pivot, JavaFX, vaadin, and HTML5. The user simply selects the required platform, and the MPS will generate the necessary code from the DataUx language user interface descriptions.

DataUx demonstrates JetBrains MPS's ability to mix external DSLs — in this case, DataUx extends the internal implementation of Java. DataUx uses important Java concepts, such as expressions, while providing an attractive visual representation. It is this language extension that allows DataUx to interact with Java ads. Typically, languages in an MPS can refer to concepts from other languages, and therefore, specifications that are modeled in other languages. The projection editor works with ASD and allows the language creator to compose, reuse and modify languages, but most importantly, it allows different subject-oriented languages to interact with each other. MPS promotes active interaction between different subject areas.

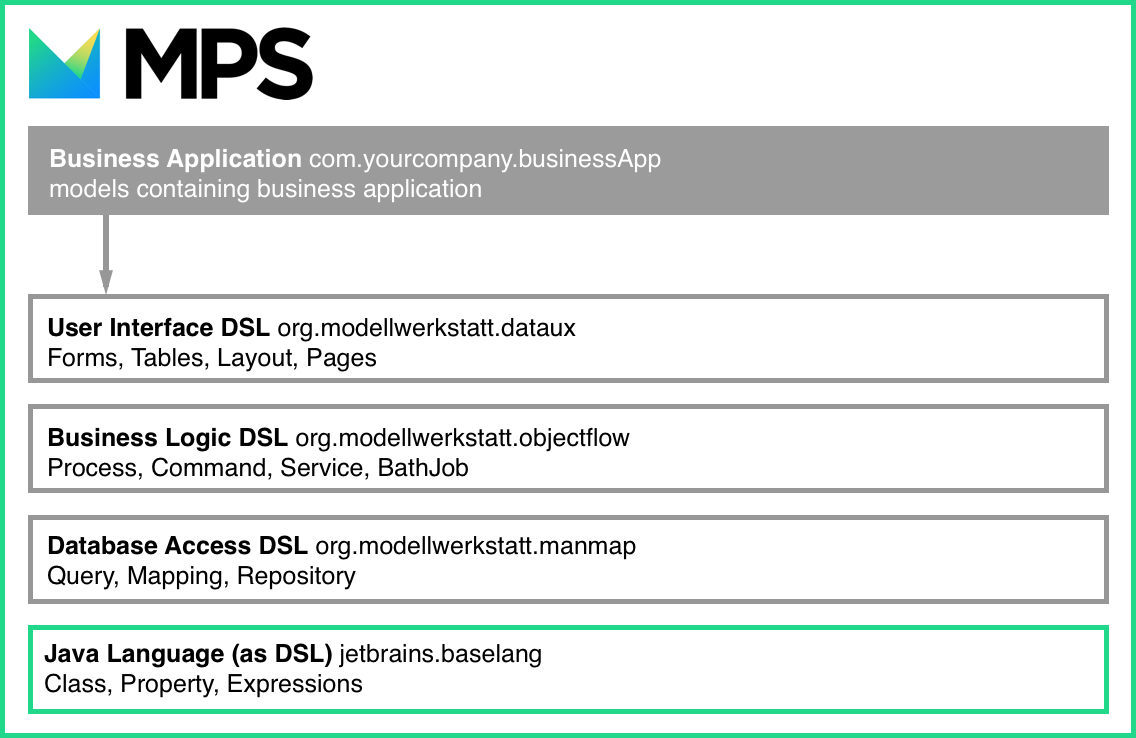

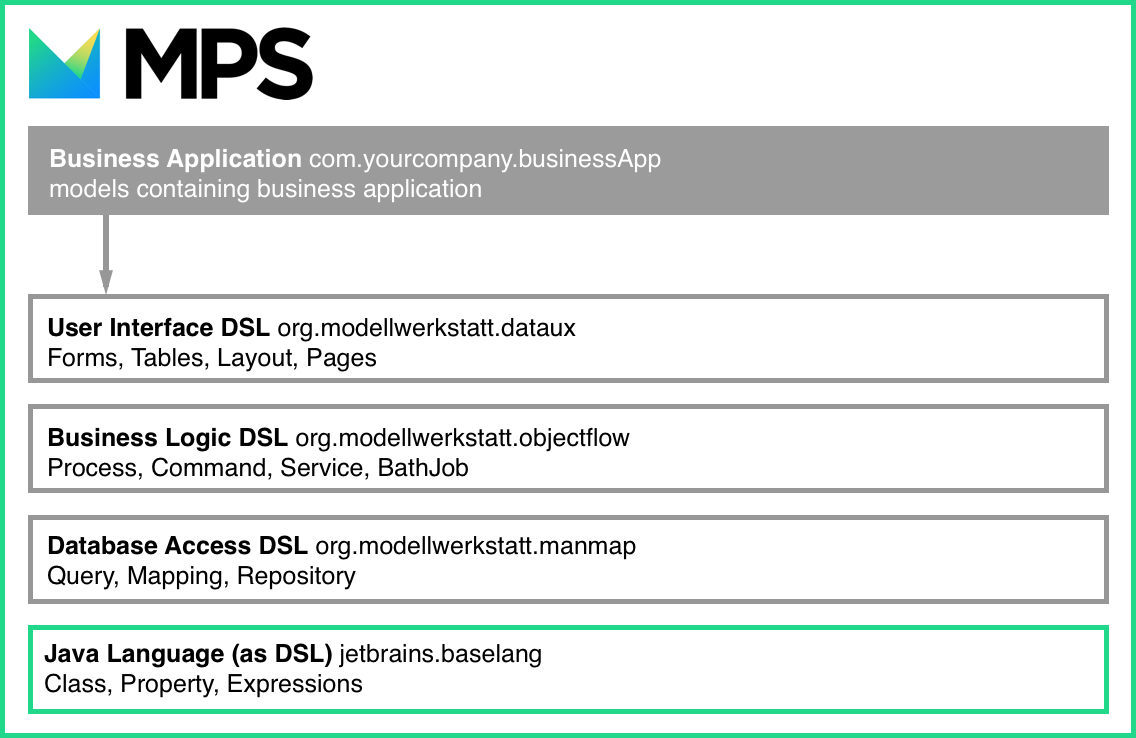

Figure 1: Different domain-specific languages for modeling business applications complement each other.

In fact, defining a user interface for a business application using DataUx is not everything. In a typical business application, a number of subject areas intersect, such as data storage (for example, SQL queries and transforms), business logic, and user interfaces. Since JetBrains MPS provides interoperability between DSLs, we developed a separate language for each specialized part of the business application (see Figure 1). Three highly specialized domain-specific languages have been created, forming a complete set of development tools. Thus, for each specific task we provide the most expressive language, while not abandoning the creation of an entire business application within a single development environment. For each subject area, business applications are provided with high-level abstractions, and no obstacles to integration are created and the formulation and understanding are kept simple, which means serviceability and high quality in the long term.

Development of business applications is related to solving problems in various subject areas, such as data storage, business logic processing, user interface design. To increase productivity and quality, not a single domain-specific language (DSL) is enough, not a few if they are not sufficiently integrated with each other. Significant improvements can only bring a holistic approach, in which several DSLs are used consistently to simulate solutions in different subject areas.

In this article, we will look at an example of DSL, with which we model standardized user interfaces for our business applications in modellwerkstatt.org . The logic inherent in DSL allows you to visualize object graphs completely and in a very simple, declarative form. We show how easy it is to embed regular Java code with which you can interact, which provides additional flexibility and security, in particular type safety. Pointing to the distinction between internal and external DSL, we will go to the JetBrains MPS and immediately consider our DSL for user interfaces. Finally, we present a number of general considerations regarding the interaction of DSL with each other and their extensions.

Internal and external DSL

Domain-specific languages are widely used in modern software development. They can be given the following definition: “programming languages that bring the level of abstraction beyond programming, defining a solution that directly uses concepts and rules from a specific subject area”. (Kelly and Tolvanen, 2008). Although general purpose languages (General Purpose Language, GPL), such as Java or Kotlin, are widely used in a wide variety of subject areas, domain-specific languages are adapted to a specific subject area, which ensures their extremely high efficiency in this area. Such languages provide abstractions adequate to the problem being solved and allow expressing solutions briefly and succinctly, and the use of such solutions often does not require the qualification of a programmer.

')

As an example, DSL is often given the query language SQL. SQL allows users to process data, tables, and databases without any programming skills. SQL provides a high level of abstraction due to specific concepts, such as “sampling” or “updating”, in the subject area “data in rows and columns”. The SQL language is clear and expressive, but it also links the user to one particular subject area. DSLs such as CSS, regular expressions and XPath are also well known. In addition to these “universal” DSLs, a number of highly specialized DSLs have been created that are used in individual organizations for capturing subject knowledge and automated generation of uniform code in general-purpose languages.

The so-called internal DSLs based on the base GPL are widespread. “Internal DSL is a special form of API in a basic, general purpose language, often also called a fluid interface” (Fowler, 2010). Internal DSL defines the concepts and operations that exist only in a specific subject area, and helps to work in this particular area. Well-known examples of internal DSL, built on Java - JMock and JooQ. However, internal DSL has significant limitations. The syntax of the internal DSL cannot violate the syntax of the basic general purpose language. Otherwise, the base language compiler would not be able to parse the resulting code and compile it. In addition, support for syntax highlighting, autocompletion, and type checking in IDEs is also limited to DSL and depends on the underlying GPL. From this it follows that, firstly, internal DSLs can be useful only to developers owning the GPL, and secondly, severe restrictions are imposed on the syntax and visual presentation.

SQL can be considered an external DSL, since it is not embedded in any other GPL and is not based on it. SQL provides its own keywords, operations, and syntax. It was conceived out of any (syntactic) connection with general purpose languages - it is completely independent. External DSLs can be optimized to ensure full coverage of information in the subject area and maximum expressiveness without any limitations on readability and clarity. The visual presentation, aesthetics and ergonomics of an external DSL can be developed to meet the requirements of not only developers, but, perhaps, the actual domain specialists themselves. Only in this case, improvements are possible in terms of formulating, communicating and understanding solutions in a particular subject area. It was these considerations that initially pushed for the creation of domain-specific languages.

However, external DSLs have a number of drawbacks. Firstly, since such a language is not based on a general-purpose language, the IDE is initially absent for it. This is especially true in cases where DSL is aimed at a very narrow subject area, that is, if the potential number of users of the language does not justify the effort required to create language tools or a full-fledged IDE. At the same time, DSL users still need intelligent tools to assist in the work and increase productivity. Second, and more importantly, external DSLs do not provide a simple way to access external artifacts, such as code in a general-purpose language or declarations stored as XML. The external DSL remains, in a sense, isolated until additional import and export facilities (generators that produce executable code in a general-purpose language) are developed. In practice, interfacing with a complete development environment is extremely important because DSL alone does not cover all aspects of a software solution. This is where language development tools can help.

JetBrains MPS

JetBrains MPS is a language development tool that allows you to define, reuse and compose domain-specific languages and provides additional tools for these languages.

Unlike other development environments, MPS provides the broadest support tools, without relying on parsers. Usually, tools and compilers get an abstract syntax tree (ASD), parsing a textual representation of a code with a fairly specific grammar. In the future, using this structured tree, the transmitted information is converted into executable code.

In contrast to this approach, in MPS, the manipulation of the SDA is performed directly, using a projection editor. Although the projection editor is similar to a text editor, the user edits the tree structure in real time. Text is not used to store the code - the ASD itself is saved, which eliminates the need for syntactic analysis. Consequently, syntactic ambiguity is eliminated, and semicolons or brackets are not required to distinguish concepts. The projection editor ensures the brevity and adequacy of the visual representation of the subject area. Code completion and error control are easily implemented through examining and bypassing the ASD - all this is supported in the IDE MPS without any extra tweaks. In short, MPS provides instrumental support for domain-specific languages in general, eliminating the need to implement it separately for each language.

The use of SDA as the basis of MPS gives an important advantage. Since the ambiguity of grammar is eliminated, languages can be combined by any means. Existing languages can be expanded and enriched with new concepts. Languages can complement each other, inherit functionality and features. This allows you to easily reuse existing language concepts, which speeds up development and contributes to a unified approach.

To illustrate these considerations from a practical point of view, we turn to our example.

DataUx is a Java based user interface language.

DataUx successfully demonstrates the idea of combining languages. We have created this language specifically for the specification of user interfaces of Java applications designed for intensive data processing — usually business applications, for example, for managing invoices for payment or for monitoring stockpiles. DataUx provides various language concepts that allow you to define data entry forms, tables for visualizing collections, and layouts. In DataUx, user interface elements are supplied with actual data values through an extended property binding. Java objects with component properties (recipients and installers for specific identifiers) are organized into an object graph. Then - and this, in our opinion, is very unusual - the whole graph is tied to the user interface. In this simple example, an order object with various properties also contains a list of order items (OrderPosition). The following screen capture shows the user interface for the Order object with its properties and order items. The second screenshot shows the specification of this user interface itself using DataUx.

Screenshot 1: Demo application user interface with one Order object containing several OrderPosition objects

Screenshot 2: Order user interface specification for a DataUx demo application in MPS

Above, in screenshot 2, the “main order page” is shown, tied to the list of Order objects. In the grid layout consisting of a single column (1 * = maximization with a weighting factor of 1), we placed two user interface elements in two lines, the first one is minimized as far as possible (-1), and the second is maximized again (1 *). On the “Delegate Form” form, the values of the six properties of the Order object are shown in two columns; the table displays a list of items for this order. The DISABLED keyword puts the entire form into read-only mode; the table and without additional configuration is available only for reading by default.

The main idea of the DataUx language is based on the binding of components and on the “master data - details” template. Each PagePane panel is able to visualize a graph consisting of objects, in which for each type of object there is a “selected object”. In our example, there are two types of objects: Order and OrderPosition. Thus, two current choices are essential: the selected order and the selected order item. In order for the currently selected object of a certain type to be loaded into the user interface element, each interface element must be tied to the corresponding object type. In separate elements of the user interface, you can access the properties of objects and bind them.

The “Delegate Form” form is tied to the order currently selected, and the table is tied to the list of positions of the selected order (recorded as Order.pos). Consequently, the “Delegate Form” can visualize the properties of the Order object, while the table can visualize the properties of OrderPosition objects in its columns. For OrderPosition, five properties are declared and the width of the corresponding columns is set.

As part of our “selected object” logic, the table is used not only to display lists of objects, but also to determine the selected object. The selected table row directly corresponds to the “selected object” of this type. In our example, when you select another row in the table, you select and define an object of type OrderPosition. Thus, the user interface was improved by visualizing the details of the order item (its properties) in another form, tied directly to the OrderPosition object.

The “order main page” from the second screenshot by type is a list of Order objects; however, if only one order is transferred, it automatically becomes the selected object of this type. This is a feature of our PagePane concept. If several orders were submitted to the page, an additional table would be required to determine the selected order. Only this would allow to realize the selected order, which is necessary for the detailed data form and the OrderPosition table. The third screen shot shows a more complex case involving multiple orders. As already mentioned, we have added a detailed form to display the properties of the selected order item (OrderPosition object).

Screenshot 3: A more sophisticated user interface for a demo application with master data – detailed data relationships

Continuing to follow this object anchoring logic, using DataUx it is not difficult to define user interfaces for complex object graphs. A user binds UI elements to an object type to access specific properties of this object. During execution, the currently selected object of the corresponding type is loaded into the user interface element. This is probably the most difficult point to understand in the DataUx language. However, this object binding logic is checked by the DataUx type system and a whole range of consistency checks. For intelligent editing, context-sensitive auto-completion is provided, and even "auto-completion of user interface elements".

In the context of the discussion of domain-specific languages, the relationship between DataUx and Java is noteworthy. Obviously, while DataUx is not compatible with Java syntax, it relies on Java concepts such as properties and classes. There are even Java type-based type checking rules. Moreover, external Java artifacts are mentioned among the user interface elements. How is this achieved?

JetBrains MPS comes with a full-featured Java implementation. Implementing this GPL in MPS is no different than implementing any specialized DSL. There is a good projection editor that reproduces the usual model of working with an intelligent text editor Java - supports the definition of classes and interfaces, their members, and of course, expressions. Since MPS also has a jar import tool, it can be used as a standalone full-featured Java IDE. We have expanded and expanded this Java implementation with the DataUx language. As a result, it became possible to use powerful Java concepts, especially expressions and types. Thus, DataUx received basic programming support without any additional effort.

By specifying user interface elements in the DataUx language, users can refer to declared Java objects and their properties if they are loaded into the IDE and are available in it. Intelligent access areas for class references, properties, and selections are calculated during editing. As can be seen in Figure 2, the DataUx “Table Summary Line” parameter provides a concept similar to closures with the variable “allObjects” (type - list). In the right-hand side, a Java expression is returned that returns a string (type is Java.lang.String). The example calls the static sum () method of the class MyUtil. It should be noted that in the context of this parameter, any valid Java expression can appear - from method calls to string concatenation and references to Java variables. Intelligent access areas for all links are calculated in the context of the parameter. Type checking is performed for all expressions.

The DataUx language makes full use of all existing concepts of the MPS Java language, in particular, expressions and type system processing — these elements of the language are usually extremely complex. The use of Java expressions in DataUx, despite its simplicity, gives the user additional benefits. Expressions allow you to flexibly adapt to the requirements of a specific case, without resorting to any external, non-integrated program code. The key advantage is also provided by the ability to extend other languages: while maintaining independence from the syntax of the MPS Java language, you can easily refer to concepts that are declared in this language, for example, the static method that is called in the Table Summary Line parameter.

DataUx language was developed for one of our large customers - retailers from Australia. On the customer side, eight developers implement all the necessary user interfaces on DataUx, without affecting any additional aspects of the user interface in plain Java code. After successfully defining the idea and structure of the language, the language itself was developed in a couple of days. However, the development of the user interface runtime took longer due to the complexity of implementation under several different technologies.

DataUx language is available on GitHub.

Conclusion

DataUx is a very simple and logical domain-oriented language that allows you to delegate the development of user interfaces to people without programming skills. The steepness of the learning curve is so small that almost no explanation is required. This language also makes it extremely easy to understand and maintain existing user interfaces. Moreover, the user interface specified with DataUx does not depend on the implementation technology. This is a very important advantage, as user interface technologies are changing rapidly today. Note that we already provide DataUx runtime for Apache Pivot, JavaFX, vaadin, and HTML5. The user simply selects the required platform, and the MPS will generate the necessary code from the DataUx language user interface descriptions.

DataUx demonstrates JetBrains MPS's ability to mix external DSLs — in this case, DataUx extends the internal implementation of Java. DataUx uses important Java concepts, such as expressions, while providing an attractive visual representation. It is this language extension that allows DataUx to interact with Java ads. Typically, languages in an MPS can refer to concepts from other languages, and therefore, specifications that are modeled in other languages. The projection editor works with ASD and allows the language creator to compose, reuse and modify languages, but most importantly, it allows different subject-oriented languages to interact with each other. MPS promotes active interaction between different subject areas.

Figure 1: Different domain-specific languages for modeling business applications complement each other.

In fact, defining a user interface for a business application using DataUx is not everything. In a typical business application, a number of subject areas intersect, such as data storage (for example, SQL queries and transforms), business logic, and user interfaces. Since JetBrains MPS provides interoperability between DSLs, we developed a separate language for each specialized part of the business application (see Figure 1). Three highly specialized domain-specific languages have been created, forming a complete set of development tools. Thus, for each specific task we provide the most expressive language, while not abandoning the creation of an entire business application within a single development environment. For each subject area, business applications are provided with high-level abstractions, and no obstacles to integration are created and the formulation and understanding are kept simple, which means serviceability and high quality in the long term.

References and literature

- DataUX on github

- JetBrains MPS

- Kelly and Tolvanen, 2008: Domain-Specific Modeling: Enabling Full Code Generation, Wiley-IEEE Computer Society

- Fowler 2010: Domain-Specific Languages, Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/341894/

All Articles