How Yandex taught artificial intelligence to understand the meaning of documents

Today we will talk about the new search technology "Korolev", which includes not only the deeper use of neural networks for searching by meaning, not by words, but also significant changes in the architecture of the index itself.

But why do we need technologies from the field of artificial intelligence, even if twenty years ago we were perfectly finding what we were looking for? How does Korolev differ from the Palekh algorithm of last year, which also used neural networks? And how does the architecture of the index affect the quality of ranking? Especially for Habr's readers, we will answer all these questions. And start from the beginning.

')

From word frequency to neural networks

The Internet at the beginning of its existence was very different from its current state. And it was not only the number of users and webmasters. First of all, there were so few sites on each separate topic that the first search services needed to display a list of all pages containing the search word. And even if there were a lot of sites, it was enough to count the number of words used in the text, and not to engage in complex rankings. There was no business on the Internet yet, therefore nobody was engaged in cheating.

Over time, the sites, as well as those willing to manipulate the issue, became noticeably more. And search companies are faced with the need not only to search for pages, but also to choose among them the most relevant user request. Technologies at the turn of the century did not allow to “understand” the texts of the pages and compare them with the interests of users, therefore, at first, a simpler solution was found. The search began to consider links between sites. The more links, the more authoritative the resource. And when they no longer have enough, he began to take into account the behavior of people. And it is the Search users who now determine its quality in many respects.

At some point, all these factors have accumulated so much that the person has ceased to cope with writing ranking formulas. Of course, we could still take the best developers, and they would write a more or less working search algorithm, but the machine coped better. Therefore, in 2009, Yandex introduces its own machine learning method, Matriksnet, which to this day builds a ranking formula taking into account all the available factors. For a long time, we dreamed of adding to this factor one that would reflect the relevance of the page not through indirect signs (links, behavior, ...), but “understanding” its content. And with the help of neural networks, we succeeded.

At the very beginning we talked about a factor that takes into account the frequency of words in the text of the document. This is an extremely primitive way to determine if a page matches a request. Modern computing power allows using neural networks for this, which cope with the analysis of natural information (text, sound, images) better than any other method of machine learning. Simply put, it is neural networks that allow a machine to move from word-by-search to meaning-based search. And this is exactly what we started to do in the Palekh algorithm last year.

Request + Title

More details about “Palekh” are written here , but in this post we will briefly recall this approach, because “Palekh” is the basis of “Korolev”.

We have a request for a person and the title of the page that claims to be in the top of the issue. You need to understand how they correspond to each other in meaning. To do this, we present the query text and the header text in the form of such vectors, the scalar product of which would be the larger, the more relevant the document with this header to the query. In other words, we use the accumulated search statistics to train the neural network in such a way that for similar texts it generates similar vectors, and for semantically unrelated queries and vector headers should be different.

As soon as a person enters a query in Yandex, our servers convert real-time texts into vectors and compare them. The results of this comparison are used by the search engine as one of the factors. By presenting the text of the request and the text of the page header in the form of semantic vectors, the Palekh model makes it possible to catch quite complex semantic links that are difficult to identify otherwise, which in turn affects the quality of the search.

Palekh is good, but it had a great untapped potential. But in order to understand it, we first need to remember how the ranking process works.

Stage Rankings

The search is an incredibly difficult thing: you need to find among the millions of pages the most relevant query in a split second. Therefore, the ranking in modern search engines is usually carried out using a cascade of rankings. In other words, the search engine uses several stages, each of which documents are sorted, after which the lower documents are discarded, and the tip, consisting of the best documents, is transmitted to the next stage. At each subsequent stage, more severe ranking algorithms are applied. This is done primarily to save search cluster resources: computationally heavy factors and formulas are calculated only for a relatively small number of best documents.

Palekh is a relatively heavy algorithm. We need to multiply several matrices to get the request and document vectors, and then also multiply them. Matrix multiplication is wasting precious processor time, and we cannot afford to perform this operation for too many documents. Therefore, in Palekh, we applied our neural models only at the latest stages of ranking (L3) - to about 150 of the best documents. On the one hand, it is not bad. In most cases, all the documents that need to be shown in the top ten are somewhere among these 150 documents, and you just need to sort them correctly. On the other hand, sometimes good documents are still lost in the early stages of ranking and do not get into the top. This is especially true for complex and low-frequency queries. Therefore, it was very tempting to learn how to use the power of neural network models to rank as many documents as possible. But how to do that?

Korolev: calculations in exchange for memory

If it is impossible to make a complex algorithm simple, then you can at least redistribute resource consumption. And in this case, we can profitably exchange processor time for memory. Instead of taking the title of the document and during the execution of the query, calculate its semantic vector, you can predict this vector and save it in the search database. In other words, we can do a substantial part of the work in advance, namely, multiply the matrices for the document and save the result. Then, during the execution of the query, we will only need to extract the document vector from the search index and perform scalar multiplication with the query vector. This is significantly faster than calculating a vector dynamically. Of course, at the same time we need a place to store the pre-computed vectors.

The approach based on the pre-computed vectors allowed to radically increase the depth of the top (L3, L2, L1), to which neural models are applied. New models of "Korolev" are calculated to a fantastic depth of 200 thousand documents per request. This made it possible to obtain an extremely useful signal in the early stages of ranking.

But that's not all. The successful experience of preliminary calculation of vectors and their storage in memory cleared the way for a new model, which we could only dream of earlier.

Korolev: request + document

In Palekh, only the title of the page was fed to the input of the model. Typically, a heading is an important part of a document that briefly describes its content. Nevertheless, the body of the page also contains information that is extremely useful for effectively determining the semantic conformity of a document to a query. So why did we initially limit ourselves to a headline? The fact is that in practice, the implementation of full-text models involves a number of technical difficulties.

First, it is expensive memory. To apply a neural model to the text during the execution of a query, it is necessary to have this text “at hand”, that is, in RAM. And if we put short texts into the RAM like headlines, it was quite possible on the capacities at our disposal, then it would not work with the full texts of the documents.

Secondly, it is expensive on the CPU. The initial stage of model calculation consists in projecting the document into the first hidden layer of the neural model. For this we need to make one pass through the text. In fact, at this stage we have to perform n * m multiplications, where n is the number of words in the document, and m is the size of the first layer of the model. Thus, the amount of processor time required to apply the model linearly depends on the length of the text. This is not a problem when it comes to short headlines. But the average body length of the document is significantly longer.

All this sounds like it is impossible to implement a model using full texts without a radical increase in the size of the search cluster. But we did without it.

The key to solving the problem was the same predicted vectors that we have already tested for the model on the headings. In fact, we do not need the full text of the document - it is enough to store only a relatively small array of floating-point numbers. We can take the full text of the document at the stage of its indexing, apply to it a series of operations consisting in the sequential multiplication of several matrices, and obtain the weight in the last inner layer of our neural model. Moreover, the layer size is fixed and does not depend on the size of the document. Moreover, such a redistribution of loads from processors to memory allowed us to take a fresh look at the architecture of the neural network.

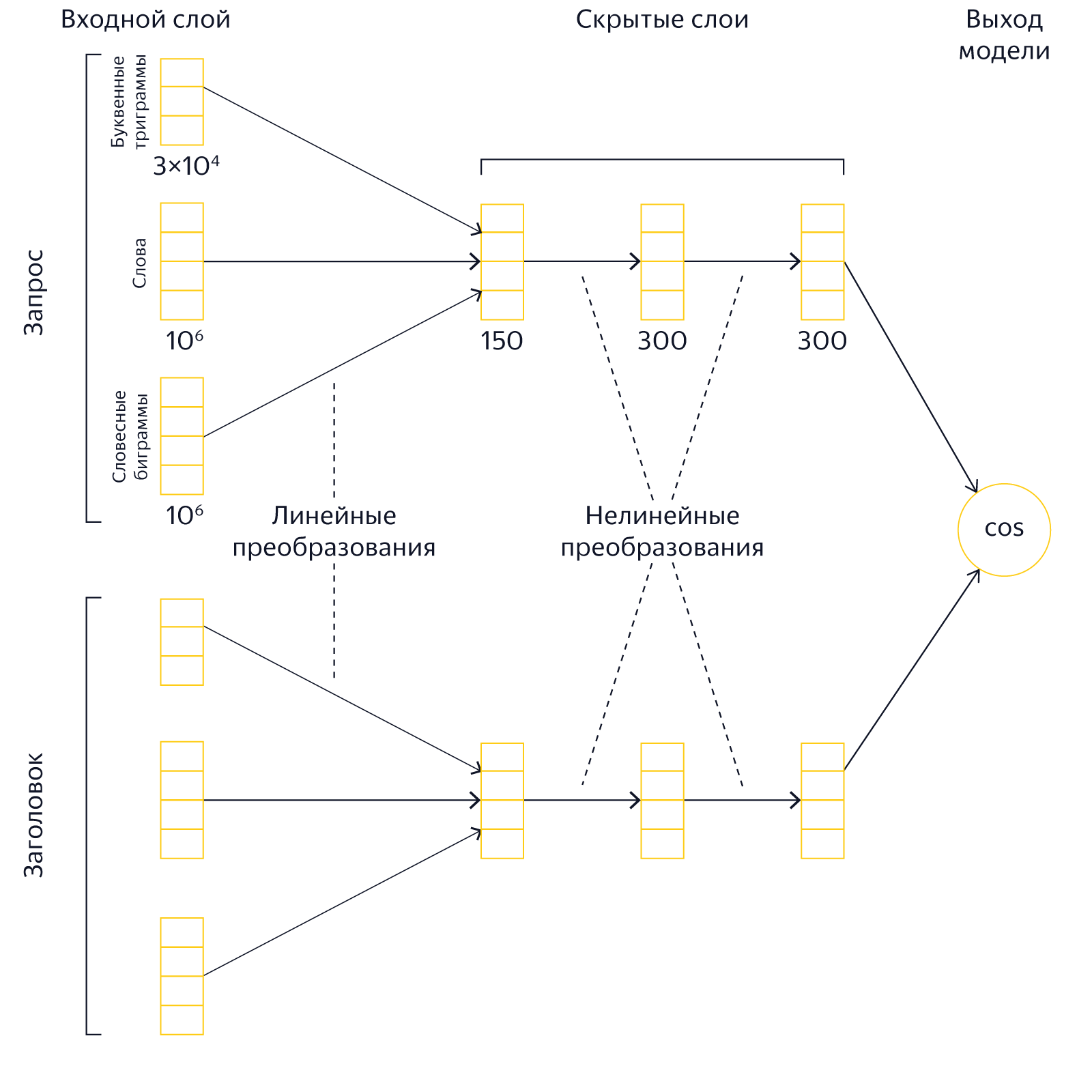

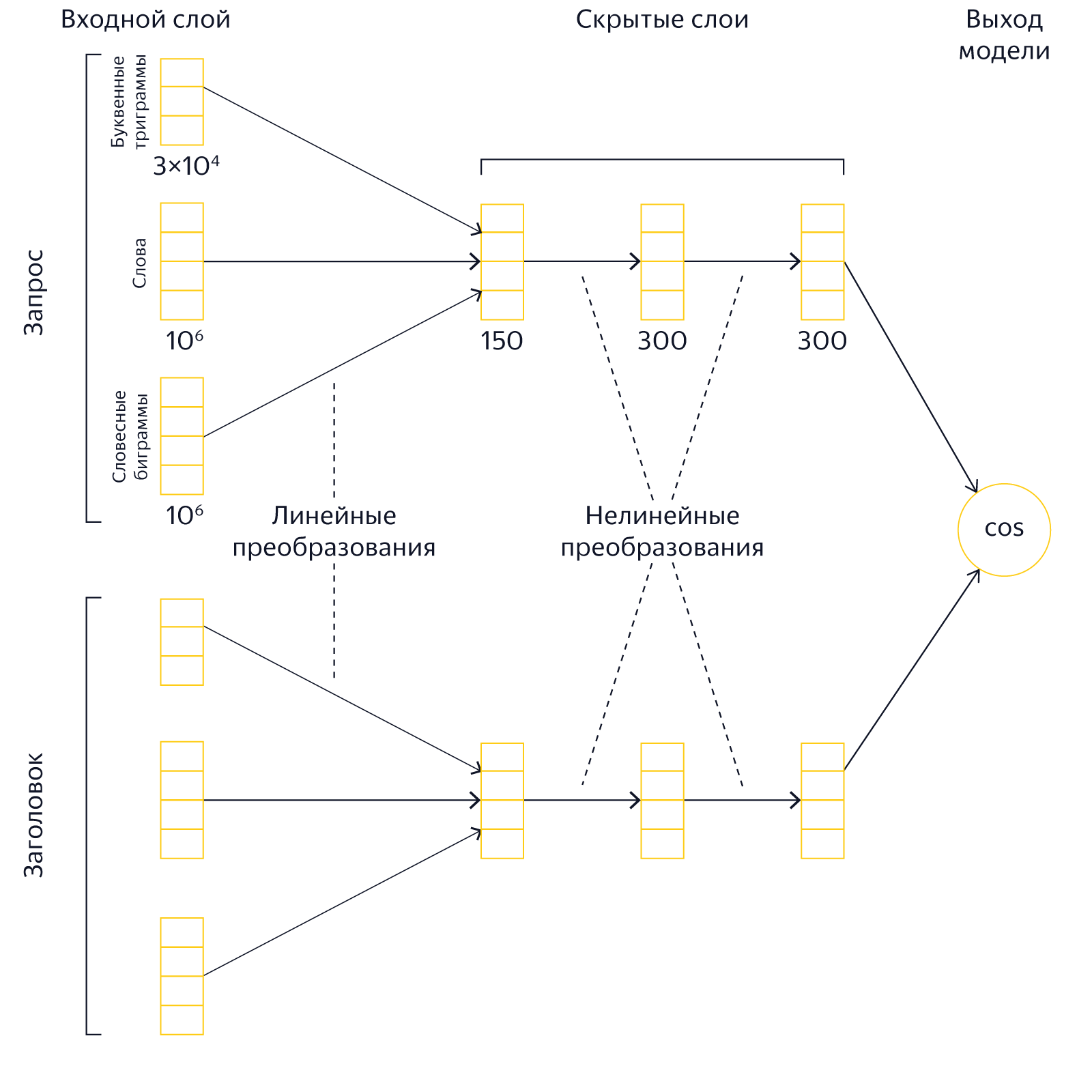

Korolev: Layer Architecture

In the old models of "Palekh" there were 3 hidden layers of 150, 300 and 300 neurons. This architecture was caused by the need to save computational resources: multiplying large matrices during query execution is expensive. In addition, for the storage of the model itself is also required RAM. Particularly strongly, the size of the model depends on the size of the first hidden layer, so in Palekh it was relatively small — 150 neurons. Reducing the first hidden layer can significantly reduce the size of the model, but at the same time reduces its expressive ability.

In the new Korolev models, the bottleneck is only the size of the last hidden layer. When using precomputed vectors, resources are spent only on storing the last layer in the index and on its scalar multiplication by the query vector. Thus, a sensible step would be to give the new models a more “wedge-shaped” shape, when the first hidden layers increase, and the last layer, on the contrary, decreases. Experiments have shown that you can get a good gain in quality, if you make the dimensions of hidden layers equal to 500, 500 and 40 neurons. As a result of the increase in the first inner layers, the expressive power of the model has noticeably increased, whereas the last layer can be reduced to a couple of dozen neurons with almost no drawdown.

Nevertheless, despite all our optimization, such a deep use of neural networks in the search requires significant computational power. And who knows how much time it would take to implement, if not for another project that allowed freeing up resources for their use, although we solved it with a completely different problem.

Korolev: additional index

When we receive a user query, among the millions of pages in the index, we begin to gradually select the best pages. It all starts with the stage L0, which is actually filtering. Most of the irrelevant documents are filtered out on it, and other stages are already engaged in the main ranking.

In the classical search model, we solve this problem using inverted indices. For each word, all the documents in which it is found are stored, and when a request comes in, we try to cross these documents. The main problem is frequency words. The word "Russia", for example, can be found on every tenth page. As a result, we have to go through every tenth document in order not to lose anything necessary. But on the other hand we are waiting for the user who has just entered his request and expects to see the answer at the same instant, so the filtering phase is strictly limited in time. We could not afford to bypass all the documents for frequency words and used different heuristics: sorted documents by some meaningless indifferent relevance query or stopped searching when it seemed to us that there was a sufficient number of good documents. In general, this approach worked well, but sometimes useful documents were lost.

With the new approach, everything is different. It is based on the hypothesis: if we take a not very large list of the most relevant documents for each word or phrase to the multi-word query, then among them there are documents that are relevant to all the words at the same time. In practice, this means this. For all words and popular word pairs, an additional index is formed with a list of pages and their preliminary relevance to the query. That is, we move part of the work from stage L0 to the indexing stage. What does this give us?

The hard time constraints of calculations are associated with a simple fact - you cannot keep the user waiting. But if these calculations can be made in advance and offline (that is, not at the moment of entering the request), then there are no such restrictions anymore. We can allow the machine to bypass all documents from the index, and no pages will be lost.

Completeness of the search is important. But no less important is the fact that at the price of consuming the RAM, we have significantly unloaded the moment of building the issue, freeing up computing resources for heavy neural network models: request + header and request + document. And not only for them.

Korolev: request + request

When we started working on a new search, we still didn’t have any confidence as to which direction would be the most promising. Therefore, we have identified two teams for the study of neural models. Until some time, they worked independently, developing their own ideas, and even to some extent competed with each other. One of them worked on the approach with the request and the document, which we have already described above. The second team approached the problem from a completely different angle.

For any page on the Internet, you can come up with more than one request. You can search for the same VKontakte using the requests [VKontakte], [VKontakte Login] or [VKontakte Social Network]. Requests are different, but the meaning behind them is one. And it can be used. Colleagues from the second team came up with a comparison of the semantic vectors of the query that the user had just entered, and another query for which we know the best answer for sure. And if the vectors (and, therefore, the meanings of the queries) are quite close, then the search results should be similar.

As a result, it turned out that both approaches give good results, and our teams have joined forces. This allowed us to quickly complete the research and introduce new models in Yandex search. For example, if you now enter the query [a lazy cat from Mongolia], then it is the neural networks that help pull out the manul information in the top.

What's next?

“Korolev” is not one specifically taken model, but a whole set of technologies of deeper use of neural networks in the search for Yandex. This is another important step towards the future, in which the Search will focus on the semantic correspondence of queries and pages no worse than people. Or even better.

All of the above is already working, and some other ideas are waiting in the wings. For example, we would like to try to apply neural networks at the L0 search stage, so that semantic vectors help us to find documents that are close in meaning to the query, but not at all containing the query words. We also wanted to add personalization (imagine another vector that will correspond to the interests of the person). But all this requires not only time and knowledge, but also memory and computing resources, and here we cannot do without a new data center. And Yandex already has it. But this is another story, which we will definitely tell in the near future. Follow the publications.

But why do we need technologies from the field of artificial intelligence, even if twenty years ago we were perfectly finding what we were looking for? How does Korolev differ from the Palekh algorithm of last year, which also used neural networks? And how does the architecture of the index affect the quality of ranking? Especially for Habr's readers, we will answer all these questions. And start from the beginning.

')

From word frequency to neural networks

The Internet at the beginning of its existence was very different from its current state. And it was not only the number of users and webmasters. First of all, there were so few sites on each separate topic that the first search services needed to display a list of all pages containing the search word. And even if there were a lot of sites, it was enough to count the number of words used in the text, and not to engage in complex rankings. There was no business on the Internet yet, therefore nobody was engaged in cheating.

Over time, the sites, as well as those willing to manipulate the issue, became noticeably more. And search companies are faced with the need not only to search for pages, but also to choose among them the most relevant user request. Technologies at the turn of the century did not allow to “understand” the texts of the pages and compare them with the interests of users, therefore, at first, a simpler solution was found. The search began to consider links between sites. The more links, the more authoritative the resource. And when they no longer have enough, he began to take into account the behavior of people. And it is the Search users who now determine its quality in many respects.

At some point, all these factors have accumulated so much that the person has ceased to cope with writing ranking formulas. Of course, we could still take the best developers, and they would write a more or less working search algorithm, but the machine coped better. Therefore, in 2009, Yandex introduces its own machine learning method, Matriksnet, which to this day builds a ranking formula taking into account all the available factors. For a long time, we dreamed of adding to this factor one that would reflect the relevance of the page not through indirect signs (links, behavior, ...), but “understanding” its content. And with the help of neural networks, we succeeded.

At the very beginning we talked about a factor that takes into account the frequency of words in the text of the document. This is an extremely primitive way to determine if a page matches a request. Modern computing power allows using neural networks for this, which cope with the analysis of natural information (text, sound, images) better than any other method of machine learning. Simply put, it is neural networks that allow a machine to move from word-by-search to meaning-based search. And this is exactly what we started to do in the Palekh algorithm last year.

Request + Title

More details about “Palekh” are written here , but in this post we will briefly recall this approach, because “Palekh” is the basis of “Korolev”.

We have a request for a person and the title of the page that claims to be in the top of the issue. You need to understand how they correspond to each other in meaning. To do this, we present the query text and the header text in the form of such vectors, the scalar product of which would be the larger, the more relevant the document with this header to the query. In other words, we use the accumulated search statistics to train the neural network in such a way that for similar texts it generates similar vectors, and for semantically unrelated queries and vector headers should be different.

As soon as a person enters a query in Yandex, our servers convert real-time texts into vectors and compare them. The results of this comparison are used by the search engine as one of the factors. By presenting the text of the request and the text of the page header in the form of semantic vectors, the Palekh model makes it possible to catch quite complex semantic links that are difficult to identify otherwise, which in turn affects the quality of the search.

Palekh is good, but it had a great untapped potential. But in order to understand it, we first need to remember how the ranking process works.

Stage Rankings

The search is an incredibly difficult thing: you need to find among the millions of pages the most relevant query in a split second. Therefore, the ranking in modern search engines is usually carried out using a cascade of rankings. In other words, the search engine uses several stages, each of which documents are sorted, after which the lower documents are discarded, and the tip, consisting of the best documents, is transmitted to the next stage. At each subsequent stage, more severe ranking algorithms are applied. This is done primarily to save search cluster resources: computationally heavy factors and formulas are calculated only for a relatively small number of best documents.

Palekh is a relatively heavy algorithm. We need to multiply several matrices to get the request and document vectors, and then also multiply them. Matrix multiplication is wasting precious processor time, and we cannot afford to perform this operation for too many documents. Therefore, in Palekh, we applied our neural models only at the latest stages of ranking (L3) - to about 150 of the best documents. On the one hand, it is not bad. In most cases, all the documents that need to be shown in the top ten are somewhere among these 150 documents, and you just need to sort them correctly. On the other hand, sometimes good documents are still lost in the early stages of ranking and do not get into the top. This is especially true for complex and low-frequency queries. Therefore, it was very tempting to learn how to use the power of neural network models to rank as many documents as possible. But how to do that?

Korolev: calculations in exchange for memory

If it is impossible to make a complex algorithm simple, then you can at least redistribute resource consumption. And in this case, we can profitably exchange processor time for memory. Instead of taking the title of the document and during the execution of the query, calculate its semantic vector, you can predict this vector and save it in the search database. In other words, we can do a substantial part of the work in advance, namely, multiply the matrices for the document and save the result. Then, during the execution of the query, we will only need to extract the document vector from the search index and perform scalar multiplication with the query vector. This is significantly faster than calculating a vector dynamically. Of course, at the same time we need a place to store the pre-computed vectors.

The approach based on the pre-computed vectors allowed to radically increase the depth of the top (L3, L2, L1), to which neural models are applied. New models of "Korolev" are calculated to a fantastic depth of 200 thousand documents per request. This made it possible to obtain an extremely useful signal in the early stages of ranking.

But that's not all. The successful experience of preliminary calculation of vectors and their storage in memory cleared the way for a new model, which we could only dream of earlier.

Korolev: request + document

In Palekh, only the title of the page was fed to the input of the model. Typically, a heading is an important part of a document that briefly describes its content. Nevertheless, the body of the page also contains information that is extremely useful for effectively determining the semantic conformity of a document to a query. So why did we initially limit ourselves to a headline? The fact is that in practice, the implementation of full-text models involves a number of technical difficulties.

First, it is expensive memory. To apply a neural model to the text during the execution of a query, it is necessary to have this text “at hand”, that is, in RAM. And if we put short texts into the RAM like headlines, it was quite possible on the capacities at our disposal, then it would not work with the full texts of the documents.

Secondly, it is expensive on the CPU. The initial stage of model calculation consists in projecting the document into the first hidden layer of the neural model. For this we need to make one pass through the text. In fact, at this stage we have to perform n * m multiplications, where n is the number of words in the document, and m is the size of the first layer of the model. Thus, the amount of processor time required to apply the model linearly depends on the length of the text. This is not a problem when it comes to short headlines. But the average body length of the document is significantly longer.

All this sounds like it is impossible to implement a model using full texts without a radical increase in the size of the search cluster. But we did without it.

The key to solving the problem was the same predicted vectors that we have already tested for the model on the headings. In fact, we do not need the full text of the document - it is enough to store only a relatively small array of floating-point numbers. We can take the full text of the document at the stage of its indexing, apply to it a series of operations consisting in the sequential multiplication of several matrices, and obtain the weight in the last inner layer of our neural model. Moreover, the layer size is fixed and does not depend on the size of the document. Moreover, such a redistribution of loads from processors to memory allowed us to take a fresh look at the architecture of the neural network.

Korolev: Layer Architecture

In the old models of "Palekh" there were 3 hidden layers of 150, 300 and 300 neurons. This architecture was caused by the need to save computational resources: multiplying large matrices during query execution is expensive. In addition, for the storage of the model itself is also required RAM. Particularly strongly, the size of the model depends on the size of the first hidden layer, so in Palekh it was relatively small — 150 neurons. Reducing the first hidden layer can significantly reduce the size of the model, but at the same time reduces its expressive ability.

In the new Korolev models, the bottleneck is only the size of the last hidden layer. When using precomputed vectors, resources are spent only on storing the last layer in the index and on its scalar multiplication by the query vector. Thus, a sensible step would be to give the new models a more “wedge-shaped” shape, when the first hidden layers increase, and the last layer, on the contrary, decreases. Experiments have shown that you can get a good gain in quality, if you make the dimensions of hidden layers equal to 500, 500 and 40 neurons. As a result of the increase in the first inner layers, the expressive power of the model has noticeably increased, whereas the last layer can be reduced to a couple of dozen neurons with almost no drawdown.

Nevertheless, despite all our optimization, such a deep use of neural networks in the search requires significant computational power. And who knows how much time it would take to implement, if not for another project that allowed freeing up resources for their use, although we solved it with a completely different problem.

Korolev: additional index

When we receive a user query, among the millions of pages in the index, we begin to gradually select the best pages. It all starts with the stage L0, which is actually filtering. Most of the irrelevant documents are filtered out on it, and other stages are already engaged in the main ranking.

In the classical search model, we solve this problem using inverted indices. For each word, all the documents in which it is found are stored, and when a request comes in, we try to cross these documents. The main problem is frequency words. The word "Russia", for example, can be found on every tenth page. As a result, we have to go through every tenth document in order not to lose anything necessary. But on the other hand we are waiting for the user who has just entered his request and expects to see the answer at the same instant, so the filtering phase is strictly limited in time. We could not afford to bypass all the documents for frequency words and used different heuristics: sorted documents by some meaningless indifferent relevance query or stopped searching when it seemed to us that there was a sufficient number of good documents. In general, this approach worked well, but sometimes useful documents were lost.

With the new approach, everything is different. It is based on the hypothesis: if we take a not very large list of the most relevant documents for each word or phrase to the multi-word query, then among them there are documents that are relevant to all the words at the same time. In practice, this means this. For all words and popular word pairs, an additional index is formed with a list of pages and their preliminary relevance to the query. That is, we move part of the work from stage L0 to the indexing stage. What does this give us?

The hard time constraints of calculations are associated with a simple fact - you cannot keep the user waiting. But if these calculations can be made in advance and offline (that is, not at the moment of entering the request), then there are no such restrictions anymore. We can allow the machine to bypass all documents from the index, and no pages will be lost.

Completeness of the search is important. But no less important is the fact that at the price of consuming the RAM, we have significantly unloaded the moment of building the issue, freeing up computing resources for heavy neural network models: request + header and request + document. And not only for them.

Korolev: request + request

When we started working on a new search, we still didn’t have any confidence as to which direction would be the most promising. Therefore, we have identified two teams for the study of neural models. Until some time, they worked independently, developing their own ideas, and even to some extent competed with each other. One of them worked on the approach with the request and the document, which we have already described above. The second team approached the problem from a completely different angle.

For any page on the Internet, you can come up with more than one request. You can search for the same VKontakte using the requests [VKontakte], [VKontakte Login] or [VKontakte Social Network]. Requests are different, but the meaning behind them is one. And it can be used. Colleagues from the second team came up with a comparison of the semantic vectors of the query that the user had just entered, and another query for which we know the best answer for sure. And if the vectors (and, therefore, the meanings of the queries) are quite close, then the search results should be similar.

As a result, it turned out that both approaches give good results, and our teams have joined forces. This allowed us to quickly complete the research and introduce new models in Yandex search. For example, if you now enter the query [a lazy cat from Mongolia], then it is the neural networks that help pull out the manul information in the top.

What's next?

“Korolev” is not one specifically taken model, but a whole set of technologies of deeper use of neural networks in the search for Yandex. This is another important step towards the future, in which the Search will focus on the semantic correspondence of queries and pages no worse than people. Or even better.

All of the above is already working, and some other ideas are waiting in the wings. For example, we would like to try to apply neural networks at the L0 search stage, so that semantic vectors help us to find documents that are close in meaning to the query, but not at all containing the query words. We also wanted to add personalization (imagine another vector that will correspond to the interests of the person). But all this requires not only time and knowledge, but also memory and computing resources, and here we cannot do without a new data center. And Yandex already has it. But this is another story, which we will definitely tell in the near future. Follow the publications.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/336094/

All Articles