Design and Mathematics of Clicker Games

Incremental games are awesome and mysterious. It seems that they violate the usual logic of good game design, and yet they manage to attract a solid player base. Let's examine them in more detail to uncover their secret.

What is an incremental game?

The player presses the button, the number increases. Pressing again, the number increases again. The player continues to press, and gradually unlocks the function, increasing the number per player. Numbers grow, even when you are not playing. And this process is repeated forever .

')

In essence, this is the general structure of the "incremental" game. It seems simple, even primitive, but in the gameplay there is an unexpected depth and appeal. Game styles can vary from commercially successful and casual Clicker Heroes and AdVenture Capitalist to more experimental or hardcore examples such as Candy Box , Cookie Clicker and Sandcastle Builder .

Cookie Clicker , the very beginning.

What is the most important thing in an incremental game? Although there are many variations and experiments in this genre, the fundamental aspects of design are:

- the presence of at least one currency or number

- which increase at a given speed with minimal effort, or without effort at all,

- and which can be spent on increasing the rate of growth.

It is the cycle of accumulation, reinvestment and acceleration that determines the foundations of the genre and distinguishes it from games in which there is simply an increasing score. For example, in a remarkable Cookie Clicker, the player seeks to increase the number of "cookies", which initially increases by clicking on a huge cookie, and then spends cookies to buy upgrades that allow you to create even more cookies.

One of the important features of such games is that the number can increase without the direct participation of the player and even without his presence. Therefore, many people call incremental games “idle games” (games that play by themselves), you can leave them and return to them at any time. Although it is an important function, I do not think that it is decisive and that is why players like these games. The most outstanding feature is the infinite growth of numbers, so it is more useful to call such games "incremental".

Psychology of growing numbers

What attracts players so much to these games? The reasons are many, but the two most important are how incremental games use the unique facets of human psychology.

The first, often referred to in the discussion of incremental games, is known as the Skinner Box . These experimental chambers, named (to his disappointment) in honor of the behaviorist B.F. Skinner, were created to study the behavioral conditioning of animals. An “operant conditioning chamber” usually contains an animal that can receive a reward (for example, food) as a reaction to performing an action (for example, pressing a button). It is noteworthy that after mastering the response mechanism, the observed animals continued to perform actions, even if they gave a reward only after long intervals or randomly.

By analogy, systems that periodically reward users or players for repetitive actions are often ironically called “Skinner boxes”, because the neurological feedback loop they create can be incredibly addictive . This structure is most obvious in incremental games: the player performs an action (presses or waits), and is periodically awarded for his efforts by increasing numbers. This in itself is not always bad, and this mechanic is often used. Many games have to train players to perform certain actions in the game system and use positive rewards (points, experience) and negative results (death) to show the player the correct way to pass. In incremental games, the use of this mechanics is simply much more obvious.

The second psychological support of incremental games is our passion for accumulation and the fear of loss . Our brain is designed so that it does not like to lose, and vice versa, it gives us a strong desire to accumulate.

In incremental games, both of these sides are used. Since the amount of the base currency always increases, even when you are not playing, it reduces the anxiety from the fear of loss: you can safely do something else without being afraid that you will lose "money." In addition, in combination with the weak skills of counting our brain, we get pleasure from the growing numbers, even if these numbers are devoid of external values. Therefore, even though it looks ridiculous, just an increasing amount gives us pleasure.

Again, this property is used in an incremental game in an explicit way, but to a varying degree it is used in most games: this is why “points” have become such a common player reward mechanism.

The "ceiling" of accumulation in Clash of Clans exploits the fear of loss: you "lose" potential profits if you do not enter the game often.

The origins of the genre

The earliest examples of using incremental mechanics can be found in the first generation of MMO games of the late 1990s. Since the MMO had a subscription model, they had to encourage the player to play as long as possible. Part of this task was solved by creating vast worlds and complex social systems, but another technique was also used: placing the player on the treadmill: you killed several rats and got a level! Killed some more and got a new one. Now the rats do not give enough experience, so you go to killing slugs, and so on. The player always runs to the next goal, but in fact does not get anywhere

There is a powerful action / reward cycle in this mechanism. Crucially, the time invested to get each new reward becomes more and more. The most famous is the grinding of EverQuest levels, the curve for increasing the levels of this game is so steep that the more players spend time, the more they actually become relatively less powerful. Despite this, the game's reinforcement loop could be incredibly tempting. EverQuest was one of the first games that caused a wide discussion of gaming addiction .

The 2002 Progress Quest game created by Eric Fredricksen has become a satire to this endless grind. It can be considered the first example of a true incremental game (as opposed to the incremental mechanics of EverQuest incremental mechanics). Also this game is one of the most minimalistic, because it got rid of any similarity of interaction with the player. This is a game for zero players: after creating a character, the game kills them mobs, performs quests, raises the level, without any action from the player. Despite the fact that it was almost a literal embodiment of the principle of reductio ad absurdum , critics believed that it was “much more frightening because it was interesting.”

Part of the progress bars in ProgressQuest .

A few years later, social games became the new heirs of incremental mechanics. Social games (most often on Facebook) also sought to ensure that they were played as long as possible (they did not have a subscription, but the free-to-play monetization tools then used were used). It is noteworthy that the incremental mechanics in such games was not only a reward system, but often the whole game. One of the most successful examples was the 2009 FarmVille game. In essence, it was a farm simulator, but it has very little resource management and strategic planning. The player simply buys the land on which he grows shoots (and later livestock), collects and sells the crop, buys new land, and so on, ad infinitum. At the peak of popularity, 80 million people played it.

The apparent simplicity of such games brought on criticism, and Professor Ian Bogost created a satirical deconstruction of the concept in the 2010 game Cow Clicker . Bogost invented this game to demonstrate the purposelessness of the basic mechanism of the game (click on the cow to increase the number), but was surprised and depressed that people actually played the game without irony. Despite the fact that it was an attempt to show how empty and meaningless such games really are, Cow Clicker accidentally proved the opposite.

Incremental games today

Many of today's popular mobile games (modern followers of social games) use incremental mechanics. Extremely successful Clash of Clans (2013) is framed as a strategic war game, but its combat mechanics are very simplified and create only a small part of the gameplay. The main aspect of the game is an upgrade of the base with the waste of gold and elixirs. Each of these resources is accumulated independently, but the accumulation process can be accelerated with incremental upgrades.

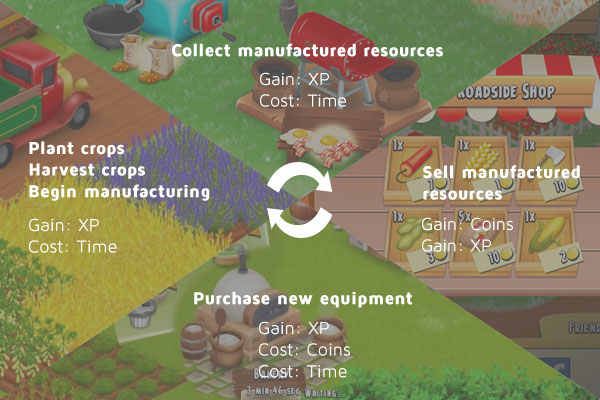

In Hay Day , created by the same company, the use of this mechanics is even more obvious. The basic cycle of the game consists only in incremental growth and reinvestment:

Game cycle Hay Day. Based on the outline from Pete Coistila's Game monetization design: Analysis of Hay Day article.

One of the most successful modern incremental games was Cookie Clicker (2013), which attracted more popular attention to games that have only incremental mechanics. Cookie Clicker uses one currency (cookies) that a player can slowly accumulate by clicking on a large cookie, and then spend on upgrades that produce cookies autonomously. Simple entourage, charming style of graphics and a gradual immersion into the absurdity of the "plot" helped the game and the genre to gain wide popularity. It became the reason for the emergence of a mass of similar games with new views on the concept, games that are being released to this day.

Is it a game at all?

Due to the simplicity of the basic mechanics and limited interaction with the system, incremental games can broaden our definition of what a “game” is. Many critics and commentators have called these games thoughtless, dull, and meaningless , while at the same time acknowledging that they may be addictive or hypnotic. Cow Clicker creator Ian Bogost, arguing about the monotony and repeatability of Cookie Clicker, reached the point that he called it one of the first games for computers, not people . But this statement contradicts the number of people who play them.

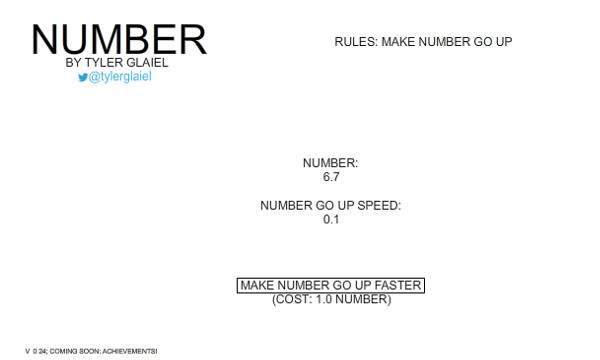

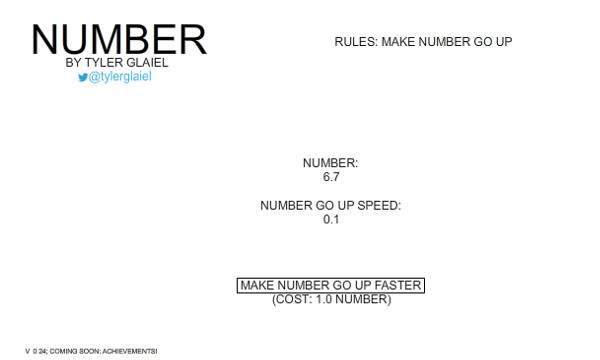

Tyler Glayel’s Number Game is a particularly obvious example.

Whatever they may seem, incremental games are in fact games. It is possible to distract for a moment from their tremendous addictiveness, because listing the reasons for their attractiveness is not the same as analyzing them from the point of view of games. Games of most genres use the instincts or subconscious desires of their players, but all this is secondary to what makes games games.

Firstly, incremental games contain mechanics that are not too obvious at first glance, the most important of which is research . In most incremental games, the player does not know the entire list of upgrades that he can buy, as he does not know the maximum limit of the main number and the speed he can reach. Exploring the limits of an interactive system is one of the distinguishing qualities of games, and incremental games are no exception. Even if they seem simple, they often have ample opportunities for research. In particular, it can be argued that Candy Box is much more devoted to research and discovery than to incremental growth, despite the fact that this feature is most obvious.

Secondly, even though incremental games expose the voidness of their premises (“make the number as large as possible”), they are in fact only means that can make the game fascinating. For example, Cookie Clicker allows you to use a strategy, because there are many ways to increase the “Number of cookies per second” metric. That is, the "game" is to optimize the system to achieve this goal. In most games of other genres, goals are really meaningless too (“make the numbers grow”), but the interesting part is pursuing this goal. Incremental games just say that straightforwardly. In his foundational work of 1937, Homo Ludens, the anthropologist Johan Huizinga considers a game that is “not serious, but at the same time completely absorbs the player. The action is not related to material interest and no benefit can be derived from it. ” These qualities are very easy to see in incremental games.

Beauty in simplicity

Incremental games in recent years are experiencing a surge in popularity, and without a doubt, we will see new examples, further study of mechanics and innovation in the premises. It would be a mistake to discard these games and consider them inexplicably addictive.

I hope that with their critical research and study of their history we will be able to appreciate the minimalist beauty and elegance of the implementation of such games. So treat them without prejudice and study this form. Do not be surprised that the game in the process of learning will carry away you for a few hours.

So, we reviewed the history of the genre and determined what makes these games unique, but have not yet delved into their design. Although incremental games look simple, their design reveals the complex and thoughtful intent of their creators. Having studied the most successful examples in the genre, we will be able to better assess the capabilities of these games and better understand how to create our own projects. Before diving into mathematics, let's look at three important factors that are easy to miss: the quality of research, the difference between a clicker and an idle game, and the importance of the integrity of the topic and graphics.

The joy of discovery

One of the most important vectors of “ interestingness ” in an incremental game is research . Many of these games start with a very simple scheme, but over time the complexity increases in a spiral. The process of exploring this complexity affects our natural passion for exploring new and hidden features. Candy Box , for example, can be considered a game, mainly aimed at the study of its system. Increasing the number of candies is just a mechanism for unlocking new content.

That is, most incremental games do not disclose their entire system from the very beginning, but limit access to new features to the levels of the primary currency. This content may be “known unknown”, as in Idling to Rule the Gods , in which some parts of the game are clearly left blank and the game explains how and when they can be unlocked. Or it may be an “unknown unknown” when the player does not know about the existence of functions until he reaches a certain level, like most of the content in Cookie Clicker . Some games contain both elements: AdVenture Capitalist informs the player about the amount of content that he can open, but contains many hidden features that arise during the game.

Looks like the road is long.

Research is an important function in the design of an incremental game, because it creates for the player a system of rewards for researching the basic mechanics of the game. If you show everything in advance, you will not only increase the entrance barrier to learning the game, but also lose the pleasure gained from gradually learning about the system.

Waiting or clicks?

Incremental games are usually focused on two intersecting, but clearly shared, basic mechanics:

- Autonomous growth, the speed of which gradually increases the player.

- The active involvement of the player, the productivity of which is gradually increasing.

Games that use the second approach either literally have the mechanics of “clicks” for growth, or some other means that require active participation of the player, for example, a restriction on the storage of resources that require frequent player intervention. In CivClicker , for example, the player is mainly in charge of managing the city, while the game has short intervals of autonomous growth. Similarly, in the games with autonomous growth, the mechanics of “clicks” can be used, but its importance gradually decreases and automated growth becomes more important. In AdVenture Capitalist, a player must first actively “click”, but quickly opens up the possibility of automating the process, after which he becomes virtually free from manually increasing numbers.

The choice of approach depends mainly on preferences and focus on the goals of the game. A game that requires active management may be more interesting for the player for a short period of time, but if it is implemented in such a way that it requires too much and frequent intervention by the player, it may violate the principles of ethical and humane game design . Similarly, a more autonomous approach with a “wait” may be less interesting for a player in the current game session, but is able to create a longer attachment to the game. This explains why the Kongregate idle games have such high retention rates . AdVenture Capitalist even informs the player about what happened in his absence, emphasizing the fact that the game does not require his constant attention:

Graphic style and theme

For incremental games, a narrative theme is often useful, on the basis of which mechanics are built (although this is very easy to miss because of the minimalism of mechanics). An interesting topic can add context to the abstract process of increasing numbers. In addition, all games benefit from choosing a good graphic style and design, and incremental games are no exception. A single aesthetics helps the game create a sense of holistic gameplay, and an intuitive interface reduces the mental load of navigation in the game, allowing the player to focus on the game itself, rather than deal with low-quality user interface elements.

This example from AdVenture Capitalist is a good illustration. The theme of the game is business management and capitalist growth (it is well suited to gameplay with constantly growing numbers). It uses the graphic style of the googie aesthetics of the 1950s. It is used everywhere (and implemented with humor), even the menus and tutorials are made “in style” and support the visual and narrative theme.

Compared to games of other genres, incremental games require much less graphics and script, but it is important not to confuse smaller requirements with a lack of requirements.

Numbers grow

The most important mechanics of incremental games is increasing numbers. Last time we defined it as follows:

- Presence of at least one number or currency

- increasing at a given speed, with minimal or no effort,

- which can be spent on increasing the rate of growth.

The third point is very influenced by the sensations of the game and its most difficult to implement qualitatively. As a very simple example, let's take the game Number Tyler Gleyel. It has these three basic points and almost nothing more: the number increases and you can spend it so that it increases faster.

When the game starts, the “growth rate” of the number is 0.1 per second. The amount of accumulated "number" can be spent on increasing speed. Here is an example of the first five purchases. The first column shows the cost, in the second - the new “number per second” speed:

| Price | Growth rate |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.2 |

| 1.2 | 0.4 |

| 1.4 | 0.7 |

| 1.7 | 1.2 |

| 2.2 | 1.8 |

Even with such a small amount of data, we can notice some of the design features of the incremental game. The first is a non-linear increase in price and benefits: you need more and more numbers to get a relatively smaller increment increment.

This is logical from the point of view of practicality: if the price / benefit would remain the same (for example, if an increase in the growth rate of 0.2 would always be 1), then there would be no variation in the results, and the growth rate would increase at a stable and predictable rate. . It would be very quickly tired!

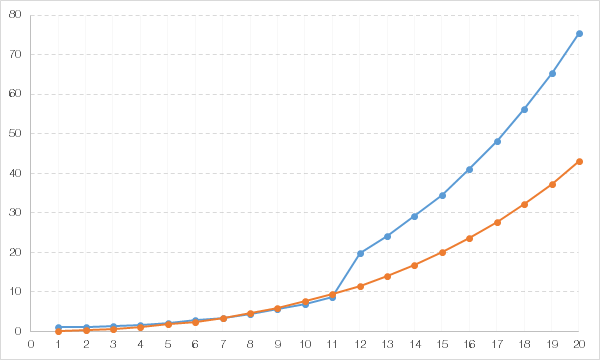

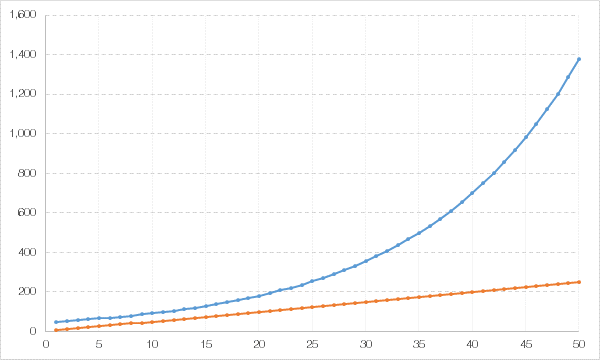

However, this is what the price (blue) and the growth rate (orange) look like for the first twenty purchases:

Blue: the price of the nth upgrade. Orange: the rate of increase per second generated after n purchases. For example, the tenth purchase costs 7 units, and it gives a growth rate of 7.6 units per second.

(You can download XLSX with the data used to create these graphs from the GitHub repository or view its equivalent in Google Sheets .)

We clearly see here that these functions are non-linear (even if we ignore the jump in the price formula at the twelfth iteration), and that the price increase quickly overtakes the increase in the growth rate. This is an important aspect of the design, because it means that the time spent waiting to purchase the next upgrade during the game process grows exponentially. That is, at the beginning the game develops very quickly, the player only needs to wait from time to time to accumulate enough for the next purchase, but gradually the speed decreases.

In most incremental games there are several sources of upgrades to increase the growth rate, and not one, as in Number. And this is the main source of research and strategies for incremental games, because the presence of several vectors of improvements, the price of which grows non-linearly, adds interesting optimization methods. If a player decides to actively invest in a single building or upgrade, then an exponentially increasing price means that at some point other development options become relatively cheaper, even if their price was initially very high. This means that the player has choices, but they need to be constantly re-evaluated, because the relative benefit for the player is constantly changing.

Linear improvements with exponential prices

Exponential price scaling is advantageous for the ever-growing investment of resources and time it requires, but most games do not use an exponential increase in the rate of growth . Why so?

On the graph from the previous section, a steady increase in the price-to-benefit ratio gives us a gap between two lines. To achieve it, we need to exponentially (or polynomially ) only the price grows (orange); the growth rate can increase linearly, and the gap between the lines will still widen.

For example, in Clicker Heroes one of the first sources of automated increase in the number is a “hero” named Treebeard. Initially it costs 50 coins and gives a growth rate of 5 per second. Its next level is 53.5, but it still gives an additional speed of 5. The first fifty purchases look like this (the price is blue, the growth rate is orange):

Note that for simplicity, we ignore the cost of other Clicker Heroes price / speed mechanics .

The “growth rate” function here is the usual straight line, because each purchase increases it by a given value of 5, that is, the formula is very simple: the total speed per second is simply the number of upgrades purchased multiplied by 5 (that is,y = 5 x ).

However, the price increases with a constant factor. The incremental price of each additional level is minimal at first; on the graph we see that for the first twenty purchases the gap between the lines is about the same. But then it increases significantly, requiring more and more for each subsequent upgrade.

The formula for the price function is actually widely used in many incremental games:

P r i c e = B a s e C o s t × M u l t i p l i e r ( #O w n e d )

In our example with Treebeard, the base price is 50, the “Multiplier” variable is 1.07, so the prices of the second level are 50 × 1 , 07 1 = 53 , 5 , third level50 × 1 , 07 2 = 57 , 245 and so on.The Multiplier value determines the curvature of the line: the higher the value, the steeper the price curves. (If the value of 1, we obtain a linear curve price.)

In Clicker Heroes used as a growth factor of 1.07 for all 35 upgradable characters, and for all buildings Cookie Clicker value is 1.15. Interestingly, all businesses in AdVenture Capitalist use different multipliers, but they are all in the range from 1.07 to 1.15. Frequent use of the same multiplier in different games means that the curves obtained within these limits are balanced and convenient.

However, some games deviate from these values. In multiplayer incremental game with Steam Monster, a factor of 2.5 was used, which increased very steeply.

As mentioned above, exponential price scaling allows you to balance several upgrade methods, providing a way to minimize the return of funds for each method. Due to this, part of the tactical balancing becomes an integral element of the price formula itself, and not just a clear constraint, invented by the designer. Because even if a certain resource is sometimes or even almost always “better”, its exponentially increasing price means that it will not be possible to use only it.

Let's look at an example of a list of improved buildings from Cookie Clicker :

| Building | Base price | Base growth rate |

|---|---|---|

| Cursor | 15 | 0.1 |

| Grandma | 100 | 0.5 |

| Farm | 500 | four |

| Factory | 3,000 | ten |

| Mine | 10,000 | 40 |

| Shipment | 40,000 | 100 |

| Alchemy lab | 200,000 | 400 |

| Portal | 1,666,666 | 6,666 |

| Time machine | 123 456 789 | 98 765 |

| Antimatter Condenser | 3 999 999 999 | 999 999 |

| Prism | 75 000 000 000 | 10 000 000 |

The first one is that the base price of each subsequent upgrade is almost five times higher than the previous one (except for the last few). Such increases by half the order guarantee that the player will have enough time to enjoy each newly discovered resource; if the price increases were lower, then it would be possible to unblock them too quickly, if they were higher, there would be a risk that the player would get tired of waiting for the next unlock.

At the same time, the growth rate (in this game, cookies per second) increases only by about a third for each additional level. This means that while buildings generate more revenue in numbers, they are in fact less and less efficient relative to their value.

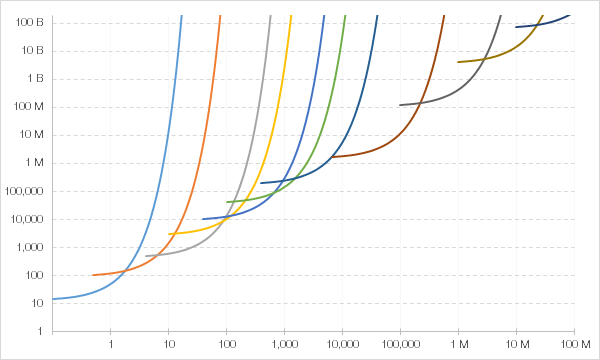

However, since each building follows the same price increase formula. P r i c e = B a s e C o s t × 1 , 15 ( #O w n e d ) , then each building actually follows a very similar pattern. The graph below shows the line for each of the 11 buildings with their first 200 upgrades. On the Y axis, the logarithmic price is plotted, on the X axis, the logarithmic growth rate. (Since these are exponential functions, the logarithmic scale reveals their similarity better than linear.)Each of the lines represents a separate building with a price on the Y axis and a growth rate on the X axis (both have a logarithmic scale). This is a visualization of the curvature of price to profit, which we discussed earlier.

Therefore, even though these buildings seem to be very different, since nominally each of them produces and costs much more than the previous one, their formulas for exponential prices create curves that are relatively similar. This creates a system that the player can optimize.

Efficiency calculation

Although at first glance incremental games are devoted to increasing numbers, in fact the goal in them is to increase numbers as quickly as possible , which creates depth of gameplay for fans of the genre. A player always has many options for development and selection of several improved resources (usually with additional characteristics that we will discuss later), that is, the difficulty of the game lies in evaluating these options. Is it worth buying a cheaper upgrade that a player can afford right now, or wait until he can accumulate to the next level?

Since we want to buy all the upgrades as a result, the best approach would be to evaluate the optimal order of purchase. Imagine a situation in which we produce 5 units of a number per second (n p s = 5 ), and we have a choice between two upgrades. The first is 20 (c o s t a = 20 ), and will increase the growth rate by 1 (r a t e a = 1 ). The second has a price c o s t b = 100 , but its growth rater a t e b = 10 .The first option is cheaper, but it is also less cost effective.

Well, let's try to buy A, and then B:

- We wait and accumulate over 20 / 5 = 4 , 0 seconds, then buy A.

- Now we are waiting 100 / ( 5 + 1 ) = 16 , 67 seconds, then buy B.

- Now we have speed n p s = 16 , for which we spent20 , 67 seconds.

And if we did the opposite?

- Wait and save 100 / 5 = 20 , 0 seconds, then buy B.

- Now we are waiting 20 / ( 5 + 10 ) = 1 , 33 seconds, then buy A.

- We got n p s = 16 , and it took us21 , 33 .

That is, it seems that buying A and then B looks more efficient because 20 / 5 + 100 / ( 5 + 1 ) < 100 / 5 + 20 / ( 5 + 10 ) . You can summarize this example and get something like this:

c o s t anps+costb(nps+ratea)<costbnps+costa(nps+rateb)

But it is only useful for comparisons between two possible upgrades, and not so useful when we have many options. We need to simplify the formula to isolate the variables for only one upgrade (the derivation of which is described in detail in this terrific article by Adam Babcock). As a result, we get the following:

c o s t an p s +costa( n p s + r a t e a )

Now we can apply this formula to any possible upgrade, and because of the transitivity of inequalities, the least result will give us what we need to buy next (with some exceptions that should not be considered at this level of analysis). This greatly simplifies the process of finding the most effective way to optimize.

Obviously, this is useful to the player, but also useful for the designer. Knowledge of the most effective use of various elements of the game makes it possible to detect the existence of unwanted peaks in time-consuming and to ensure the optimal speed of the game process, chosen by the author.

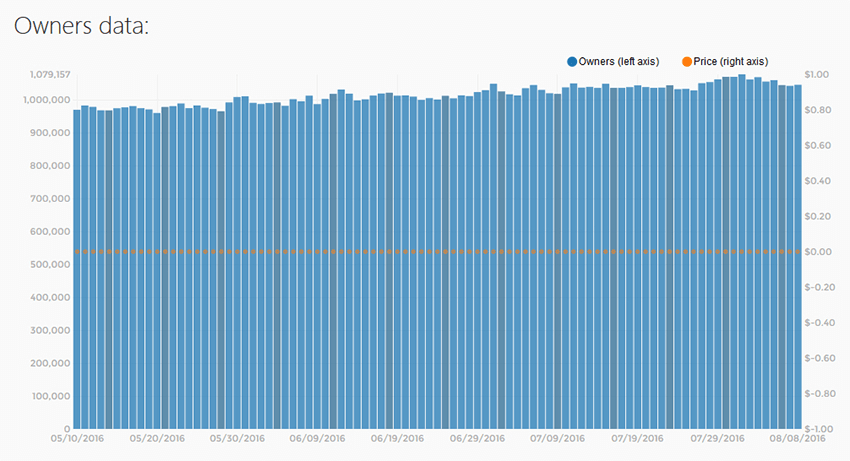

Calculating the optimal game scenarios allows us to also compare different incremental games: we can limit the incomparable variables to the time it takes to achieve the desired level of increment per second. The graph below shows the time required to achieve a given rate of increase in the number per second for AdVenture Capitalist (green graph) and Cookie Clicker (brown) games when buying buildings in the most efficient way (for simplicity, we ignore other aspects of games):

X axis: time, Y axis: growth rate (logarithmic scale); green chart: AdVenture Capitalist; brown chart: Cookie Clicker.

It is noteworthy that the graphics of these two games are very similar in the return of high speeds nps with respect to the increasing amount of time. Both grow incredibly fast in the first 8-10 hours (about 500 minutes), but then the growth rate becomes much more marginal. With the increase in the number of new buildings, the graphics gradually become flat. Therefore, in most incremental games, along with the main buildings being improved, there are other purchased resources. One of the most important of these is the game reset feature, which allows the player to go all the way along the curve from the start.

Spirally increasing complexity of upgrades in incremental games can make their development frightening. But the designer does not need to precisely calibrate each element. The beauty of complex non-linear systems means that the designer has enough high-level balancing to create fascinating chains of upgrades. For the player, the task of researching the system and finding the optimal sequence is interesting and complex, the task of the designer is only to create such a complex system.

"New Game +" and other features

The New Game + feature allows the player to reset all his progress in exchange for some permanent bonus. That is, all purchased buildings and other resources may be zeroed out, but after that, a permanent bonus is added to all calculations per second when restarted. That is, all purchased buildings and other resources can be reset, but when you play anew, multiplication is added to all calculations per second.

It does not change any fundamental formulas of the game, it just means that the player will reach the asymptotic "plateau" faster and faster. In essence, this feature allows you to extend the basic gameplay due to its faster passage. However, this cannot continue indefinitely, and over time, enthusiastic players will achieve a kind of “end of the game”.

In Clicker Heroes, the rise rewards players with a new currency for which upgrades can be bought.

Another common feature for expanding the gameplay is a simple increase in the complexity of buildings being improved. So far we have considered only the most popular incremental upgrade method using the exponential price function. Along with them, there are other upgrades that usually either give a one-time simple increase in the total number per second, or in some way change the variables of the base price and the rate of growth.

For example, in Clicker Heroes there are upgrades that increase the base number per second for a “hero”, as well as others that increase the base number per second for all the “heroes”. Although these similar functions do not change the basic mechanics of an incremental game, they can expand the opportunity space for player research and add complexity to the game optimization process. In addition, like the mechanics of "New Game +", the volume of upgrades can also be used to extend the game, until it rests on the inevitable "plateau" of progress.

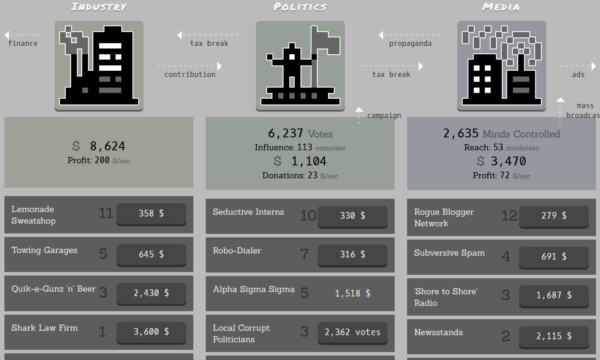

In Conspiracy Clicker there are three separate tree of interconnected upgrades.

Multiply (exponentially) further

Although it was not an exhaustive study of the design of incremental games, we carefully considered their fundamental aspects. Briefly list them for designers and developers:

- Create and develop a sense of exploration.

- Consider options for active and passive play (and ideally use both).

- Do not neglect the theme and graphic style.

- Create exponential price scaling. The most commonly used form Price = BaseCost \ times Multiplier ^ {(\ # \: Owned)} where multiplier matters from 1.0 before 1.15 .

- Provide the player with various ways to optimize.

- Increase gameplay time by strategically using dumping and mechanics to increase complexity.

If you are interested in exploring the topic more deeply, then explore the subreddit for incremental games — an excellent community of developers and designers where you can get advice and draw ideas. If you want to immediately immerse yourself in the implementation of your ideas, the Cookie Clicker developer has created an online tool in which you can easily create similar games. This is a great way to experiment, without wasting time on self-laying the foundation. If you need something more complicated, the creator of CivClicker wrote a great logic page for implementation in HTML and JavaScript.

Further growth

The modern boom of incremental games began in 2013 with games such as Cookie Clicker and Candy Box , followed by a wave of similar projects. They were mostly games in the “indie” style, however, they were usually fair and played right in the browser. They are rarely monetized by other means, except by showing ads on platforms like Kongregate.

Everything began to change at the beginning of 2015, and now a huge number of players from different platforms play the most popular incremental games. AdVenture Capitalist and Clicker Heroes , for which they released the Steam version in the spring of last year, now have more than 4.5 million owners, and in two weeks more than 100 thousand people play in them. Amazing statistics, and this is only for one platform!

Although it is difficult to calculate a specific number of players on all platforms, the increase in popularity is obvious. Another indicator - since the beginning of 2015, the number of subreddit subscribers for incremental games has almost doubled.

The number of owners of Sakura Clicker, another popular incremental game (data from SteamSpy )

I don't think this should surprise us. In addition to the qualities described above, incremental games are becoming more accessible. These are games that can be played in very short sessions (for example, on the road, at work or at school), they are easy to start and finish, and they have systems that gradually unfold over a long time.

The simplicity of launching in the phone, in the browser tab and the process of performing without participation of the player create low costs for switching to the game, which attracts many players. I think it is significant that, for example, there are almost no incremental games on game consoles, because they are meant for “thoughtful”, slow gameplay, and the power of incremental games is that they can be run “from time to time”.

Transition to mobile platforms

One of the biggest changes and sources of growth has been the growth of mobile gaming. Most of the most popular incremental games for PCs and browsers now have versions for iOS and Android. The two largest incremental Steam I have mentioned, Clicker Heroes and AdVenture Capitalist , have more installations on iOS and Android than on Steam.

On both mobile platforms, there is an excess of all kinds of incremental games. It would be logical to assume that high retention rates for players in incremental games, shown by Kongregate , will continue on mobile platforms. Incremental games are starting to attract increasing attention from mainstream mobile game developers. Bandai Namco has released a Katamari mobile game called Tap My Katamari . This is something like an endless runner (roller?) Connected to an idle clicker:

Another hit was Neko Atsume: Kitty Collector , released in the fall of 2016 in English. Although there is no “clicker” mechanics or the usual accumulation of numbers, the fundamental gameplay loop is similar. Cats gradually and slowly unlock, almost independently of the player, who can only consistently open cute cats.

Constant innovation and experimentation

I was surprised by the variety of new incremental games that were pushed by the first projects. While the most popular incremental games hone their design more and more, there are also a growing number of more experimental games that use incremental mechanics in a new way.

For example, the Dreeps Alarm Playing Game is an idle RPG that the player does not play at all. Changing the scope of what is considered an RPG gameplay, it has become a serious version of the ironic Progress Quest .

Incremental games have shown an incredible ability to fully absorb the features of other genres. First of all, this happened with the RPG, but it seems that the incremental gameplay can take on the role of games of any other types. Sometimes this is just a superficial substitution, for example, in the case of Time Clickers , which borrowed the visual style of multiplayer arena fps.

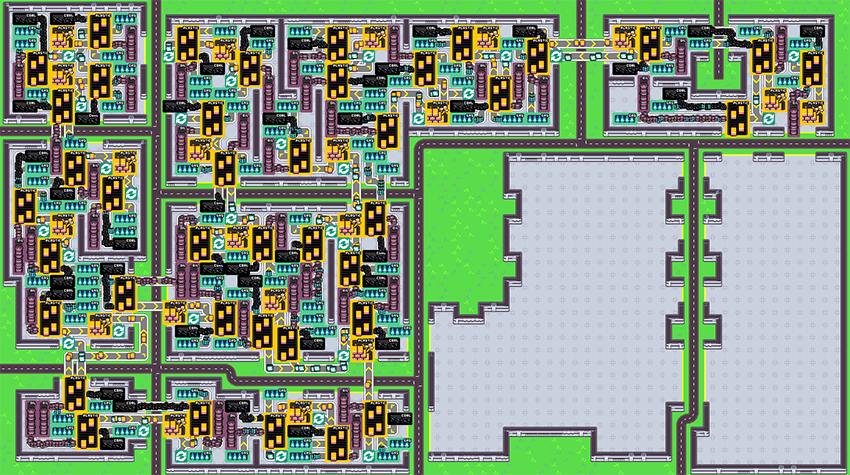

Others are more ambitious, for example, Roguathia , a fully automated roguelike , in which the player controls both the adventurers and the dungeon itself, endlessly improving both sides. Or like Factory Idle , which cuts off all the possibilities of choosing and placing buildings for building games, leaving only the upgrade tree and the developing city:

Another area for experimentation is multiplayer mechanics. In games such as Clicker Heroes and Idle Online Universe, there is an optional multiplayer game mechanics, in which overall progress is achieved by collective click-through (the mechanics are similar to the multiplayer Monster clicker from Steam released last summer). This is somewhat reminiscent of Peter Molyneux's experiment / advertising game Curiosity - What's in the Box of 2012, in which the players jointly moved on to unlock the prize (well, or not ).

Critics inattention

Despite the vitality and growing appeal, incremental games are rarely discussed by critics and gaming media. When articles discuss incremental games, they are almost always described as meaninglessly addictive or their attractiveness is explained by the fact that they constantly award the player . The reasons for this may be many, and an important role here is played by the well-established prejudice against the "casual" games. However, I suspect that there is an unspoken fear of addiction to such naked examples of grind mechanics, which is the basis of other types of gameplay that we like to recognize in part.

All this was true for 2015, but now designers are increasingly beginning to critically evaluate incremental games. More impartial assessments also appear, for example, as in the case of game designer Liz England, who notes in the discussion of an abandoned incremental game prototype:

“In this space there are a lot of interesting possibilities for the designer. The good side is economic systems, which in time open up new opportunities, which creates a sense of research. ”

There is even a formal scientific interest: in an article from the Digital Games Research Association conference, the incremental games from parodies turned into “re-creating aesthetics,” which led to the expansion of this subgenre and the framework for defining the very concept of games.

I suspect that in the future we will see more in-depth research on incremental games. Game designer Frank Lants in a 2011 article about Cow Clicker, Ian Bogosta, noted that she was a joke to a lesser extent than it seems, and I believe that today this opinion can be considered prophetic:

Why do we suppose that we should feel condescension to those who have not perceived the satirical thrust of the game? Perhaps they did not understand the joke the way Ian conceived it , but did they really have to understand it?

He wanted to show that the game is so simple, so limited, transparent and shallow cannot be playable, that it can not be played. And they did not understand this part of the joke.

But maybe it happened because the joke was wrong. They played it. They wanted to play with this ridiculous, primitive system. Some of them thoughtlessly clicked in time with the main clock. Others deliberately used suitable cycles ( like real gamers! ) Arising in any system, even if the system has no functions.

Some of them accumulated clicks with automated scripts, others vehemently denied the autoclickers heresy.

Incremental future

Although such games look like reductio ad absurdum , parodies of game mechanics, but I think that incremental games have a bright future. There is something in human nature that allows us to enjoy the pleasure of optimizing arbitrary systems.

As a game designer, I admire it, because, as it seems to me, incremental games have been able to throw away much of what seemed necessary for the game. Although it’s hard for me to see the attractiveness of Minecraft's some kind of jail servers , this is an under-explored area of design, and I’m glad that the number of such games is only increasing.

Afterword

While I was writing and publishing this article, even more interesting news about incremental games appeared! Therefore, I want to add an afterword and talk about them.

It is worth mentioning two more interesting incremental games that are worth seeing. Kittens Game is the “Dark Souls of the world of incremental games”, in which there is an interesting narrative component and a mechanism for unfolding gameplay. Also appreciate the Spaceplan , which is probably one of the aesthetically ambitious incremental games of the moment. Another thing worth reading is an article in the Wall Street Journal about a simulator game from South Korea that is very similar to incremental games. Also read this criticism of No Man's Sky , which can be perceived as a complaint about the mechanics of the game, similar to the incremental one (even though the article does not use this term).

I also recommend an excellent article with Gamasutra on the classification of players in idle games . And in contrast to what I said about consoles, it seems that incremental games also come to consoles . And finally, Anthony Pecorella (a link to the research I cited above) gave an excellent report to GDC Europe with an analysis of the mathematics of incremental games. It can be read in the GDC Vault .

List of games mentioned

Of course, this is not an exhaustive list of incremental games (for a detailed list, look at IncrementalGame.com and AlmostIdle.com ), but I will list all the games mentioned in this article:

- AdVenture Capitalist

- Candy box

- Clicker heroes

- Cookie Clicker

- Curiosity - What's in the Box? (already inactive)

- Dreeps Alarm Playing Game

- Factory idle

- Monster (temporary mini-game Steam with a summer sale, is already inactive)

- Neko Atsume: Kitty Collector

- Reactor idle

- Roguathia

- Sakura clicker

- Tap My Katamari

- Time clickers

Let me remind you that you can download XLSX with the data used to create graphs in the article from the GitHub repository or view its equivalent in Google Sheets .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/335754/

All Articles