IOS UI tests: why you need to believe in QA friendship and development, but don't flatter yourself

Recently, we took up the implementation of UI testing in iOS for iFunny. This path is thorny, long and holivar. But I still want to share my first steps in this direction with smart people. We don’t pretend to the truth - we tried everything on our own product. Therefore, under the cut there is some information about what iFunny is on iOS and why we needed UI + a lot of feedback on tools and code examples.

What is iFunny on iOS

iFunny is a popular humor and memes app in the USA with a monthly audience of 10M. Read more about how everything was started, you can read here . Application development on iOS started 6 years ago, and we still do without any revolutionary inclusions:

- 99% of the code we keep on Objective-C;

- we adhere to classical MVC with accurate divisions into modules;

- actively working with Cocoapods for dependencies;

- We use our own webm content player: third-party solutions have slowed down, did not let the content get stuck, and so on. In the case of iFunny, which is completely UGC, this topic is critical;

- Fork from SDWebImage is used not only for images, but also for the rest of the downloaded content;

- for API, select RestKit - a fairly mature framework, with few years of work with which there were almost no problems.

Unit tests

')

Unit tests we use for critical moments of business logic and Workarounds. Here is a fairly simple test: we are testing the method of our model, which checks for new content coming to it.

- (void)testIsNewFeaturedSetForContentArrayFalse { FNContentFeedDataSource *feedDataSource = [FNContentFeedDataSource new]; NSMutableArray *insertArray = [NSMutableArray arrayWithArray:[self baseContentArray]]; feedDataSource.currentSessionCID = @"0"; BOOL result = [feedDataSource isNewFeaturedSetForContentArray:insertArray]; XCTAssertFalse(result, @"cid check assert"); feedDataSource.currentSessionCID = @"777"; result = [feedDataSource isNewFeaturedSetForContentArray:insertArray]; XCTAssertTrue(result, @"cid check assert"); } The second class of tests that we use are the tests that are needed to verify the class override rules. At one point, we needed to write many similar classes for the analytics system, differing in a set of static methods.

Xcode and Objective-C did not provide any solution to protect against incorrectly written code.

Therefore, we wrote this test:

- (void)testAllAnalyticParametersClasses { NSArray *parameterClasses = [FNTestUtils classesForClassesOfType:[FNAnalyticParameter class]]; for (Class parameterClass in parameterClasses) { FNAnalyticParameter *parameter = [parameterClass value:@"TEST_VALUE"]; XCTAssertNotNil(((FNAnalyticParameter *)parameter).key); XCTAssertNotNil(((FNAnalyticParameter *)parameter).dictionary); } } Here it is verified that the class has 2 static methods, key and dictionary, necessary for the correct operation of sending events to analytics systems.

UI tests

We have already studied quite well the work with UI-elements and thought about the test environment in the process of writing tests for Android. It turned out like this:

- separate flavor for launching the application with preliminary settings, so as not to set them manually in the tests every time;

- Moki for the API using WireMock, so that every time you don’t crawl over the answers to the server and do not depend on it;

- we played with the process of launching tests and set up a rather convenient flow on CI Bitrise, during which tests are uploaded and run on real devices at Amazon Device Farm, we can see the reports with screenshots and videos in the same place by clicking on the link from Bitrise.

We couldn’t put it on stream, as we were developing a new version and waited for everything to settle. Now we are actively restoring and developing a test base.

The turn came in iOS, and we, the QA team and the iOS developers, started by gathering together and arguing for ourselves why we need autotests. It was an important ritual, and he acted almost like a mantra:

- reduce the amount of manual checks;

- automate regression;

- Ensure continuous testing of the application so that at any time you know what state it is in.

Instruments

We started with the selection of tools. On the agenda were 3 main frameworks, which are now most often used for testing mobile applications. We tried on each of them.

Appium is a popular cross-platform framework. Argued that it will become the standard in testing mobile applications in the near future. A few months ago, we decided to test it as half a year ago with iOS 10, but we were a little upset: the Appium version with its support was in beta, and we didn’t really like to use the unstable version in the sale. Appium Inspector, which runs on Android, could not be used either: there was no support for Xcode 8 and iOS 10. Soon they released the stable version, but waiting for us for half a year after updating the axis is highly undesirable. We decided not to torture myself or Appium.

Calabash is a cross-platform open source solution that uses the BDD approach in writing tests and has been supported by Xamarin until recently. Recently, developers have reported that support is everything. We also decided not to go further.

And finally, XCTest is Apple's native framework, which we ultimately chose. So read about the pros:

- There are no unnecessary dependencies, which we have in the project so much;

- Except Apple itself, no one from the side will bring and add bugs. We already had experience with Appium and KIF. It turned out that the bottom is still using XCTest and Apple's bugs are superimposed on the KIF bugs, which means sit down, boyfriend, and pick large frameworks. We certainly did not need these dependencies;

- You can use the standard languages of iOS development Objective-C and Swift: QA can easily interact with developers;

- The tested application is a black box, besides, in the test you can work with any application in the system.

Then they also considered Recorder , Apple's native tool, which is positioned as an auxiliary tool, without the hope that it will be used when writing real tests. With it, you can explore the labels of UI-elements and play with the basic gestures. Recoder itself writes code and generates pointers to objects, if this was not done during development. This is the only advantage that we were able to highlight. The minuses turned out to be much more:

- It's hard to write a test, because the UI slows down - you do some action and wait for 10-15 seconds for it to be recorded. Inconvenient;

- The code is written always different. Today I am so smart and call this element button [1], and tomorrow - “smilebutton”. Unclear;

- constant errors in the recognition of gestures. You can make the swipe left, and he will determine that it is a tap. You do tap, and this is already a swipe. Unstable;

- A broken test recorded by Recorder will most likely have to be completely rewritten again, because it will not reflect the real situation. Just WTF ?!

Developer to the rescue

And now about the problems encountered in practice: we will solve them, drawing on the development.

Black box

Plus, the black box turns into a minus: we cannot know about the current state of the application either on the device or on the simulator. We need to reset it and create, by analogy with Android, a certain environment, where the application is informed in which country we work and with which users we want to interact. All this is solved using the application launch settings.

We also needed pre-action in Xcode. In order to reset the working environment before each test, we decided to remove the installed application from the simulator to reset the user settings and everything stored in the sandbox:

xcrun simctl uninstall booted ${PRODUCT_BUNDLE_IDENTIFIER} With Environment-variables we work like this:

app = [[XCUIApplication alloc] init]; app.launchEnvironment = @{ testEnviromentUserToken : @"", testEnviromentDeviceID : @"", testEnviromentCountry : @"" }; app.launchArguments = @[testArgumentNotClearStart]; In the test, an application object is created and a dictionary (or array) with the settings that need to be passed to the application is recorded in the launchEnviroment and launchArguments fields. In the application, settings and arguments are read in the delegate at the very start of the application in the method:

- (BOOL)application:(UIApplication *)application didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:(NSDictionary *)launchOptions So we are processing:

NSProcessInfo *processInfo = [NSProcessInfo processInfo]; [FNTestAPIEnviromentHandler handleArguments:processInfo.arguments enviroment:processInfo.environment]; The TestAPIEnvHandler class implements processing of the settings dictionary and an array of arguments.

Element properties

When we started working with XSTest for UI, a problem arose: the standard set of tools does not allow reading fonts and colors.

We can only work with gestures for elements, but we cannot read the text that is written in them, take their position or other properties that are interesting for UI testing.

After searching for alternative solutions, we looked in the direction of the Accessibility API, through which UI tests work.

As a “bridge” between the test and the application, we decided to use accessibilityValue, which every visible element in the iOS SDK has.

I went to the bike, and this solution turned out:

- In accessibilityValue write json-string.

- In the test we read and decode.

- For UI elements, we write categories that define the set of fields we need in tests.

Here is an example for UIButton:

@implementation UIButton (TestApi) - (NSString *)accessibilityValue { NSMutableDictionary *result = [NSMutableDictionary new]; UIColor *titleColor = [self titleColorForState:UIControlStateNormal]; CGColorRef cgColor = titleColor.CGColor; CIColor *ciColor = [CIColor colorWithCGColor:cgColor]; NSString *colorString = ciColor.stringRepresentation; if (titleColor) { [result setObject:colorString forKey:testKeyTextColor]; } return [FNTestAPIParametersParser encodeDictionary:result]; } @end To read accessibilityValue in the test, you need to refer to it, for this, each XCUElement object has a value field:

XCUIElement *button = app.buttons[@"FeedSmile"]; NSData *stringData = [button.value dataUsingEncoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding]; NSError *error; NSDictionary *dictionary = [NSJSONSerialization JSONObjectWithData:stringData options:0 error:&error]; User interactions

The problem of gestures and actions is solved (lo and behold!) By the tool itself, thanks to a large set of standard methods - tap, double tap. But in our application there are not only standard, but also very non-trivial things. For example triple tap, svaypy on all axes in different directions. To solve this, we used the same standard methods when configuring parameters. It was not a big splinter.

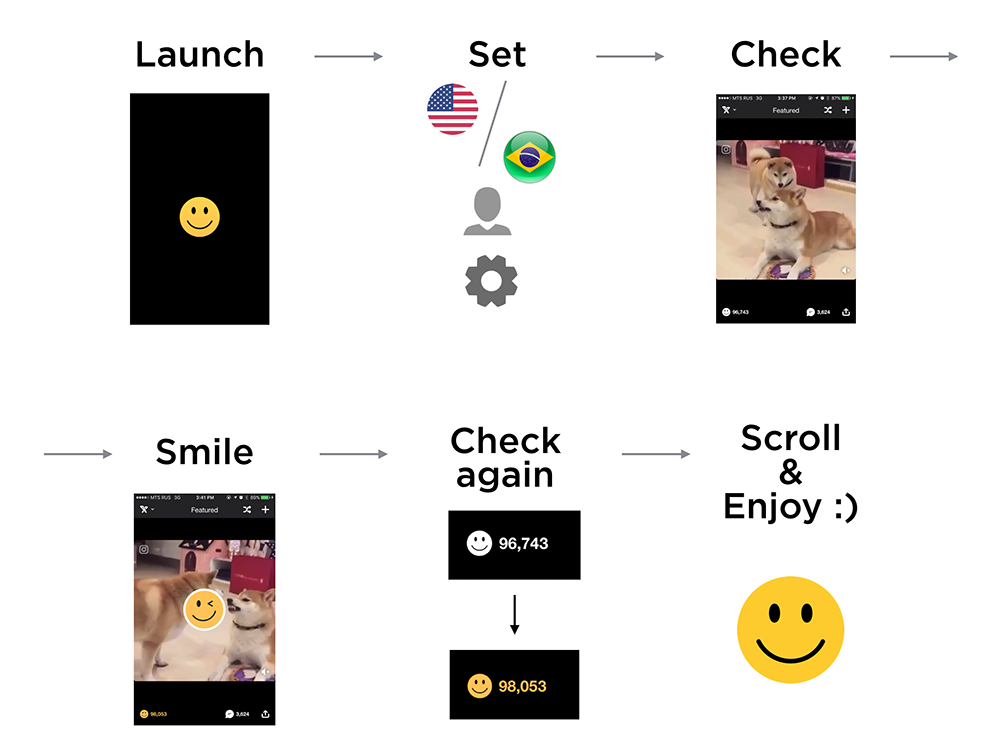

An example of a simple test using the approach:

- run iFunny with certain settings;

- choose a country;

- select the desired user;

- specify additional settings (whether this is the first launch of the application or not);

- check the opening of the tape and download content;

- make a smile;

- We check through the UI whether the content is smacked (the state of the button has changed). We continue to scroll;

- We look memes and enjoy life.

- (void)testExample { XCUIElement *feedElement = app.otherElements[@"FeedContentItem"]; XCTAssertNotNil(feedElement); XCUIElement *button = app.buttons[@"FeedSmile"]; [button tap]; [[[[XCUIApplication alloc] init].otherElements[@"FeedContentItem"].scrollViews childrenMatchingType:XCUIElementTypeImage].element tap]; NSDictionary *result = [FNTestAPIParametersParser decodeString:button.value]; CIColor *color = [CIColor colorWithString:result[testKeyTextColor]]; XCTAssertFalse(color.red - 1.f < FLT_EPSILON && color.green - 0.76f < FLT_EPSILON && color.blue - 0.29f < FLT_EPSILON, @"Color not valid"); XCUIElement *feed = app.scrollViews[@"FeedContentFeed"]; [feed swipeLeft]; [feed swipeLeft]; [feed swipeLeft]; } We did not plan to do a full test coverage, so this was the end of our experiments. It became clear that if we once decide to fully implement autotests in the process, we will use XCtest, but now we’ll do this on an ongoing basis very labor-intensively. And that's why:

- you still have to reinvent the wheel;

- QA will not be able to fully test applications without developers;

- UI-tests for our product development - this is the LUHARI functional and apply it only in exceptional cases.

PS When shooting a preview, not a single bug was hurt. Semyon continues to inspire the QA team.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/335328/

All Articles