“Alex, please kill me already”: conversational interfaces

We in UIS are now in full swing sawing the voice recognition module of the Virtual PBX. And therefore, we are watching what people who have something to say about them think about the development of conversational interfaces. Under the cut is a translation of a recent article by Alan Cooper , who, like us, thinks that the main thing in technology is its potential for cost optimization.

Reflections on conversational user interfaces

The main technological paradox of the present: it is more difficult to tell a computer what to do than it is to a computer to do it. Difficult tasks are relatively easy to accomplish with the help of digital technologies, but drawing up instructions for implementation that takes into account all the nuances and subtleties of these complex tasks is a constant challenge for the developer. The resolution of this paradox lies at the heart of professional interaction design.

Some believe that the difficulty of directing the digital mind to the right direction will become much less when we improve conversational interfaces. That is, when we can just talk to the computer, the interaction with it will become simple, clear and understandable. This opinion has been around for decades and, like the flames from burning tires in the valleys, is not at all about to fade. And as the speech recognition software is getting better - and it is very good today - the toxic flare of excitement flares up even more.

Our imagination to the Hollywood picture of easy emotional communication with the robot catching our every word, which respectfully bows every time, in a hurry to carry out our order. Machines are presented by our empathetic and diligent servants who respond to verbal commands. "Organize lunch." "Tell Jane I'll be late." "Increase sales by ten percent." "Make sure no one is watching me."

Such a vision is not only anthropomorphic, it is also fantastic. This is not just endowing computers with human qualities, it is endowing them with super-human qualities. Just because we are able to form thoughts in our head, we mistakenly believe that someone else can form the same idea based on some noise from our mouth.

If your computer recognizes the words you say, do not make a hasty conclusion from this that it understands what you mean. Your spouse, who has lived with you for 20 years, is only now beginning to remotely imagine what you really mean when you say something. Your computer will most likely never begin to understand you for the simple reason that the things you say are in principle not understandable.

A long history of misunderstanding, ambiguity, and disastrous communication of people with people should remind us that such a vision is based on what we want, and not on what actually takes place. Even if it is so difficult for people to give verbal instructions, how are we going to effectively give verbal instructions to computers?

Many people, including me, believe that this fantastic world will remain an unattainable chimera.

“Alex, turn off the light!” - this is the level of speech recognition that we have achieved now. That's cool! It's fun! Surprise your friends! This is not a killer feature, but this is what technology is capable of today, so we will see a bunch of options for using these kinds of scripts in the near future. Of course, the unconscious consequences of a raw application of technology, for example, in a smart home with built-in voice recognition, are amazingly easy to foresee. "Alex, turn off the light!" "Not this light!" "No, in another place!" "Alex, only the light in the garage!" "No, Alex, turn off and not turn on." "Only in the garage." “Damn you, Alex!”

One of the reasons that conversational user interfaces tempt us with false hopes is that modern software is extremely good at speech recognition. Unfortunately, “extremely good” is a relative concept that depends on what you need to do.

A few years ago, a good friend of mine with a lot of experience in health care conceived a project that was supposed to make it easier for doctors to solve their old-world problems with the need to make a lot of records. The therapists spend about as much time as they do on the examination of patients, so the project had a huge potential for saving time. My friend was going to give the doctors the opportunity to simply slander these recordings into a buttonhole microphone during the process of listening and probing patients. The program was built on the basis of a very functional Dragon speech recognition platform. Everything worked well, except that it did not work well enough for medical purposes. It turned out that doctors still need to read and check the text. In programs where the completeness of the task is critical, 99.9% of success means the chance of one mistake per thousand cases. When the bet is human life, this is not good enough.

Regardless of the history with the doctors, there is still a lot of value in voice recognition for many data entry applications. The latest iPhone from Apple, for example, can do text decryption of messages to voicemail. This is a wonderful handy tool to save time, because - even though 20% of words are missing or distorted - I can understand the message without having to listen to it.

Recognition of words is not at all the same as recognition of meanings, namely, values are critical for executing instructions. Voice recognition is most needed in important and complex applications designed to work in situations where the user's hands and eyes are busy. In TV commercials, it looks like this: a young, pretty girl behind the wheel of a brand new luxury car says “Call Robert” - and her attractive young husband answers the call while she continues to drive along the suburban highway that is slippery with rain.

')

In my car - an attribute of the real world - everything happens a little differently. "Call Robert." "I'm sorry I do not understand". "Call Robert." "I'm sorry I do not understand". "Dial Robert's number." "You mean Robert Jones, 555-543-1298." "Yes". "Ready." "Dial the number." "Dialing the number." And at this moment I realize that while I was busy with this excessive pronouncing, I missed my convention. From the point of view of the basic postulate of interaction design, any voice command of the user should be considered crucial, and it is precisely for this reason that the majority of automotive voice control systems are not used even once the car leaves the car dealership.

Now imagine the same degree of blunt misunderstanding and sluggish pedantic obstructionism of the system when controlling a tractor, a conveyor line, an airplane or a nuclear warhead. Such command recognition systems are not stupid. They should behave in a similar way to avoid ambiguity, because uncertainty in the dialogue between man and machine is technically unacceptable. Unfortunately, the inclusion of a voice in this interaction always creates uncertainty, and this, according to my forecasts, will never be cured.

We will inevitably use more and more conversational user interfaces in the future. Not because they are good or better than other interface design technologies, but because they are cheaper. They allow you to use software where otherwise you would have to use a human operator. So the development of this technology is driven by cost optimization, and not by user convenience.

***

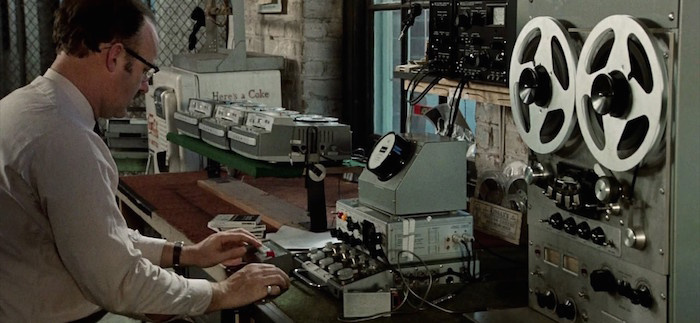

One of my favorite films is The Conversation by Francis Ford Coppola. This gloomy diamond is, in fact, a very deep and personal film of a great director, released in 1974 right after the triumph of Coppola’s life movie, The Godfather. In general, like any good detective story in the noir genre, this is a film about characters disguised as an investigation into a murder. And why I speak about him in general - everything in this film (characters, plot, theme, definition of who is a good guy and who is bad) is tied to the interpretation of how one single word was spoken.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/334316/

All Articles