Tale about NePetu, or rather not about Petya

I did not want to write a note about Petya / Nyetya / NePetya and other names of malicious code, which at the beginning of the week once again made the world shudder according to many media. My reluctance was dictated by two reasons. First of all, it was us, that is, Cisco and its division Talos (I already mentioned it here , but, apparently, I will have to tell a little more about what kind of division), we were invited to participate in the investigation of what is happening in Ukraine, and write about the results before the end of the investigation, we understand that we do not have the opportunity. And after the end of the investigation, not all of its results will be published. Secondly, I must admit that I do not share that rush around the malicious code called Nyetya, which has only been fueled by various publications and statements in recent days.

What is so unique about it that distinguishes it from other malicious programs and from the same WannaCry ? Why no one writes so much about Jaff or BitKangoroo, which were distributed at the same time as WannaCry and used similar methods? Why no one makes a report and does not discuss Untukmu, Shifu, Blackshades or the same Locky , which infected more computers than WannaCry, Petya, Misha and Nyetya combined? Why do IS specialists with a serious face discuss who used to turn Petya out of them and who spread the indicators of compromise faster than anyone? Someone calls 30 minutes, someone 37 minutes, someone “woke up” only after a few hours ...

Why did Nyetya become possible at all? Why didn’t the recommendations given by almost all experts a month and a half ago when WannaCry let me go? The victims did not install the update on the operating system (at the same time, browsers with plugins could be updated)? And the external access via SMB ports is also not closed? But it was worth doing regardless of WannaCry. These are so trivial axioms of information security that they even stopped being talked about at conferences, plunging into more complex matters — machine learning, artificial intelligence, anomaly detection, big data analytics, and so on. But what can you say if even simple things that do not require any budgets are not done?

')

When WannaCry happened (as usual, all of a sudden), everyone was so immersed in it that they stopped looking around and ask a more general question: “And what needs to be done to protect yourself from cryptographers?” Not from a specific WannaCry more than 400 modifications were found), and from all (or the maximum possible number) of ransomware programs (although the same Nyetya is not an ransomware, despite the demand for ransom). After all, this is exactly the job of information security specialists - not to plug holes after they were discovered, but to reduce the area of a possible attack by building a defense system so that it can deal with most of the threats initially.

Is it possible to catch not a specific version of a specific cryptographer, but to develop a universal option? Let's try. Without pretending to complete coverage, let’s make a list of the characteristics of most cryptographers:

It is clear that not all of these characteristics are present in every cryptographer. For example, the self-distribution function was not so often used by attackers, who, preferring point attacks, forced users to perform some action (click on a link, open an attachment, run a file from a flash drive, etc.). Not all cryptographers had the opportunity to work with the command server, acting completely autonomously. But without having one or two characteristics, the rest were still present and they could be countered with a set of protective measures. What could be the measures of protection?

Again, let's reason. In the threat prevention phase, we must:

But today one cannot be sure of 100% threat prevention - they can get on a flash drive, via a 4G modem, unprotected Wi-Fi or a company top manager who infected his personal laptop at home and brought it to the corporate network for treatment could bring them . Therefore, several years ago we suggested following the BEFORE - DURING - AFTER concept, which implies that we should spend 80% of efforts to neutralize threats, but usually allocate a third of possible resources and protective measures. Another third to put on the discovery of what can pass through protective barriers. In the discovery phase, we must:

And what about the remaining third effort? We must let them in to remedy the situation, which is unpleasant to admit, but which is possible in any company - to fight the infection or compromise that has happened. But in this case we should not bury our heads in the sand like ostriches (in fact, ostriches do not bury their heads in the ground, but such a version has gone since the times of Pliny the Elder and we are used to it), and promptly localize the problem and prevent it from spreading network, “cure” the compromised nodes and return the system to its preattached state. In the response phase, we must:

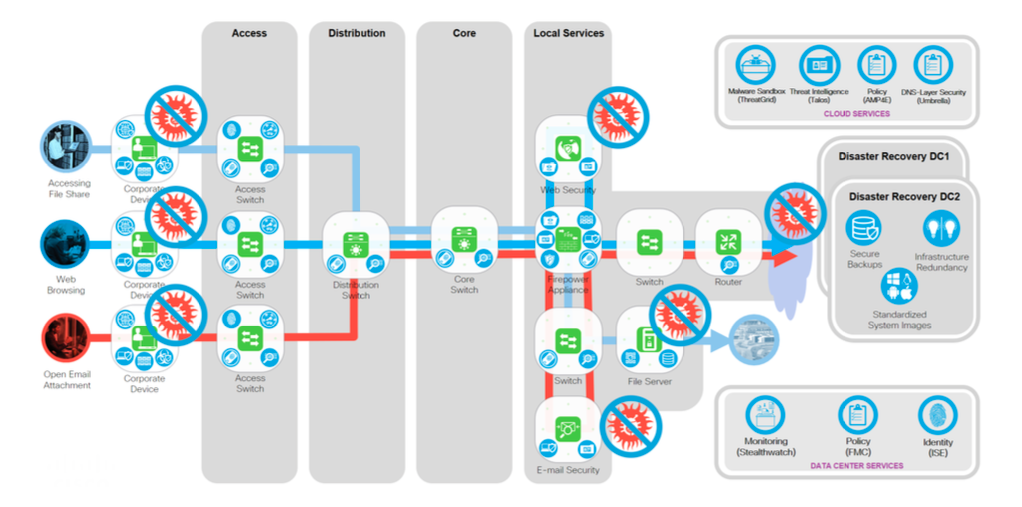

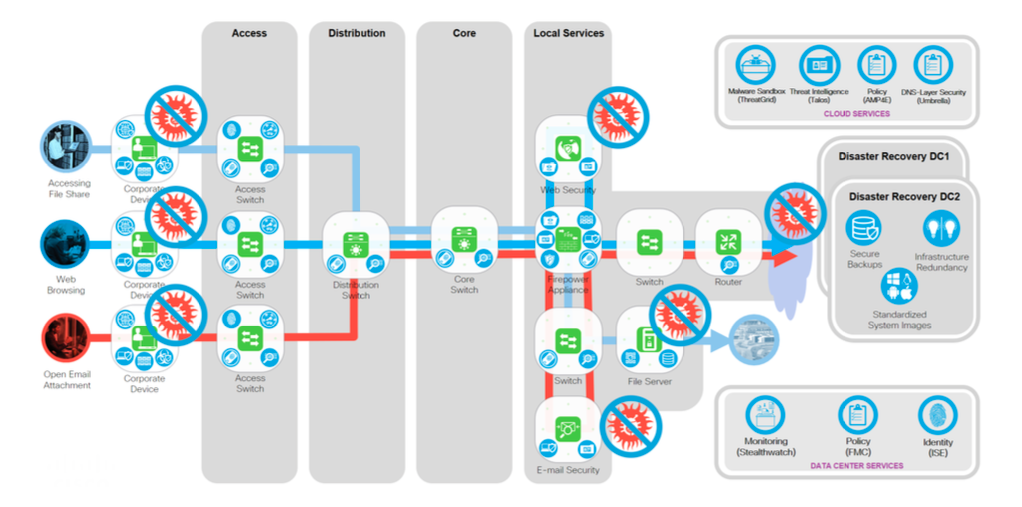

It is clear that one product does not implement the above set of tasks. Modern extortionists are still quite complex and use a variety of attack vectors so that they can withstand any one product, even the best, hung with awards and placed in various magic squares. For example, Cisco, which is the leader of the global information security market, has a whole range of technologies and solutions that can deal with this threat, at different stages of the cryptographer's life cycle, from an infection attempt to active distribution on the internal network.

But this is not just a beautiful picture. We have prepared (by the way, even before WannaCry and Nyetya) detailed technical guidelines on the design of the infrastructure to combat this threat. It was developed by us in accordance with our Cisco SAFE (Security Architecture for Enterprise) architecture, but it also examines in detail the methods of penetration of ransomware programs into the customer’s network, and methods of preventing, detecting and responding to the current life cycle of the modern threat “ TILL TIME” AFTER “.

This manual describes the whole stack of technologies that allow you to deal with extortionate software:

But Cisco would not be Cisco if it simply listed the technologies and solutions used in the flyer. We have combined them into a complete system, which allows us to obtain a synergistic effect from this integration. Each technology, each product found its place, most accurately satisfying the task. Our customers do not need to think about what and how to do to protect against the most serious threat of recent times, on which attackers earn more than $ 1 billion a year. We have tested the work of all components of the new leadership and are responsible for their performance.

If you still go back to the story with Nyetya (aka Petya.A, aka Petya.C, aka PetrWrap, aka PetyaCry, aka GoldenEye, aka ExPetr), what do we know today?

Starting with SamSam, the main victim of which was the US health authorities in March 2016, Talos warned of the risk of malware propagation using unsecured network-wide vulnerabilities. In May 2017, WannaCry made many cry, taking advantage of the vulnerabilities of the SMBv1 protocol implementation and spread widely across many systems around the world. On June 27, a new malware sample was found, quite different from the original Petya, so that people began to give it new names, such as Petrwrap and GoldenEye. Talos identifies this pattern of malware as Nyetya. Our current investigation (the original and constantly updated Cisco Talos blog entry in English is available here ) showed that this sample also uses EternalBlue and EternalRomance in combination with psexec and WMI tools to spread and infect new victims within the network. We will look at this in detail below in the “Nyetya malware functionality” section. Compared to WannaCry, there is no scanning external network component.

Identification of the initial vector is currently difficult. Early reports on the use of the mail vector have not yet been confirmed. Based on observations of the behavior of the samples “in the wild world”, we see that there are no obvious, visible external mechanisms for the reproduction of this sample of malware. We suspect that part of the infections may have used a mechanism for updating accounting software known in Ukraine, called MeDoc, which is indirectly confirmed by the manufacturer MeDoc and research colleagues. Talos continues to search for the original attack vector.

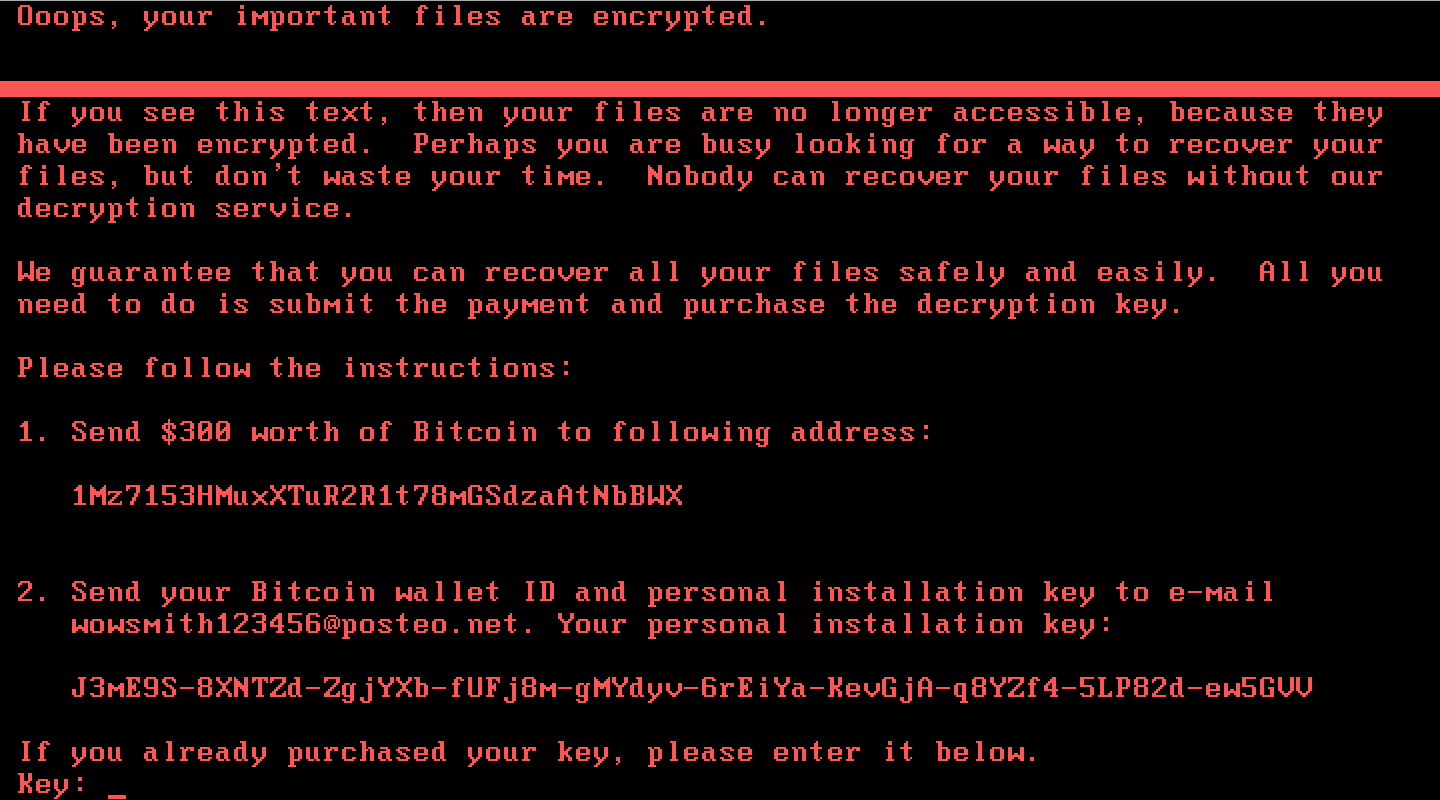

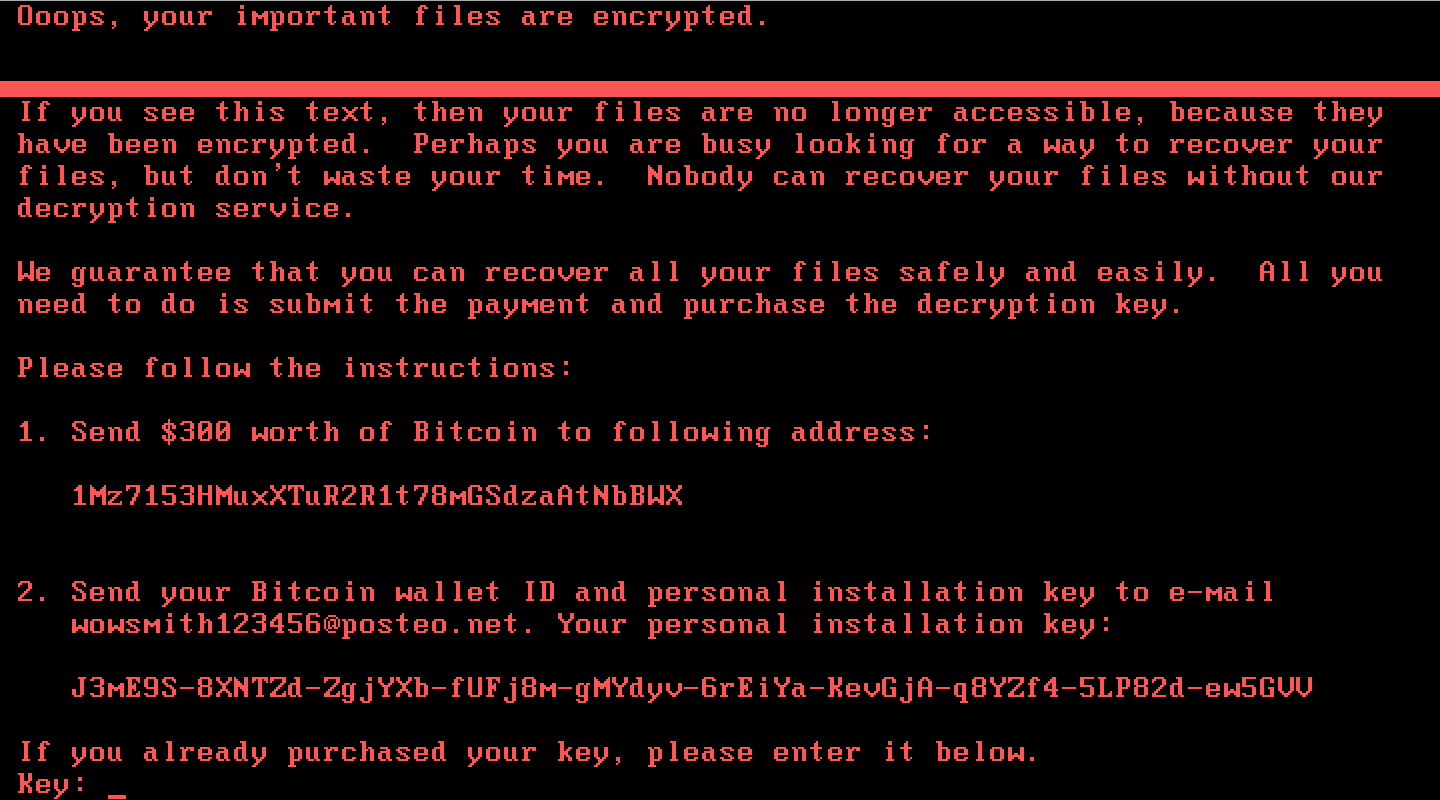

As with any malware, Talos does not recommend paying a ransom. Keep in mind that for this particular sample of malicious code it is also meaningless, since the mailbox that was supposed to be used to exchange information about payments and get the decryption keys was blocked by the mail provider posteo.de. It was the only way of communication used by attackers to obtain information about payments and to obtain decryption keys. There are no other methods for connecting malware to remote management servers and retrieving decryption keys from them (in the absence of such). Thus, Nyetya is not a cryptographer who works for ransom, but is simply a sample of malware that destroys data and systems that can reach.

Perfc.dat, responsible for spreading the malware, contains an embedded executable in the resources section. This executable is created as a temporary file in the user% TEMP% directory and starts the named pipe with a parameter containing the GUID. Further, the main executable module Perfc.dat interacts with this executable module through the named pipe. For example:

It seems that .tmp-executable code is based on Mimikatz, a well-known open source toolkit for retrieving user passwords and logins from the system’s memory and uses several methods to do this. However, Talos confirms that this code is not an exact copy of Mimikatz.

The received login / password pairs are used to infect remote systems via WMIC and PsExec. For example:

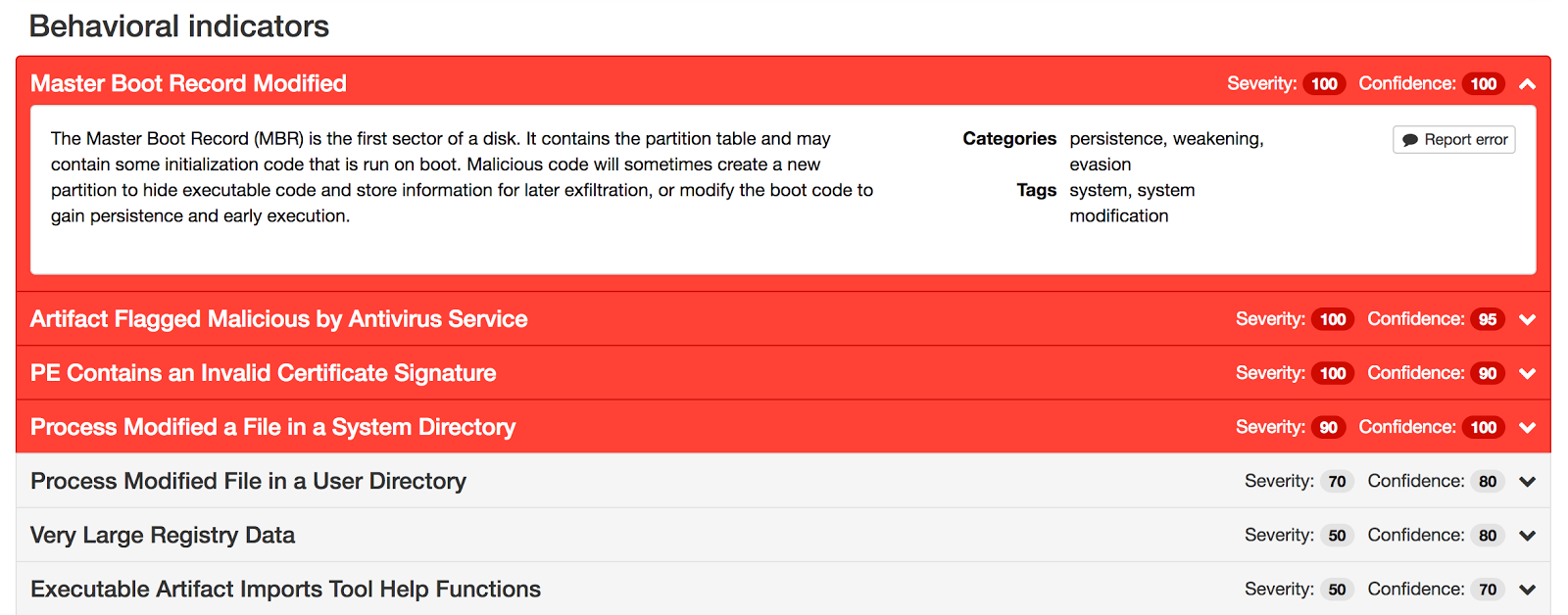

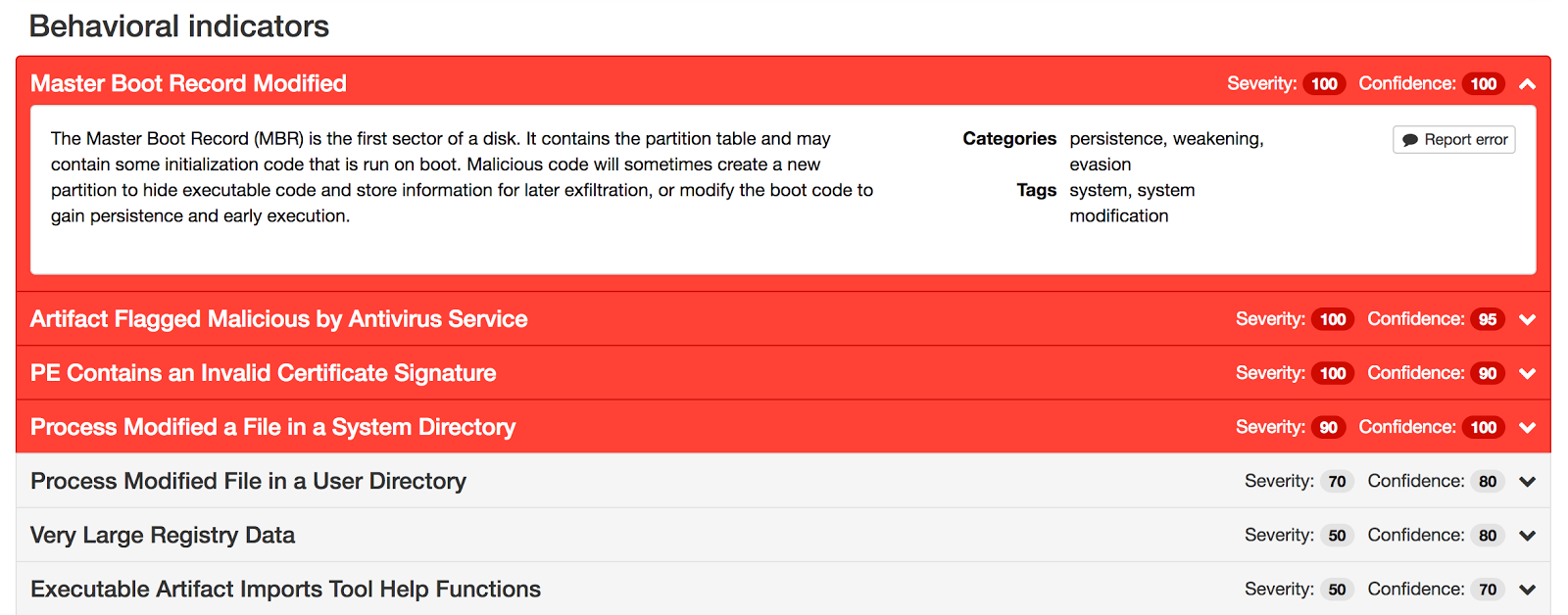

In its investigation, the Talos team discovered that the compromised systems had the file “Perfc.dat”. Perfc.dat contains the functionality necessary to further compromise the system, and contains one unnamed exported function, # 1. The library attempts to obtain system administrator privileges using calls to SeShutdowPrivilege and SeDebugPrivilege on behalf of the current user through a call to the Windows API AdjustTokenPrivileges. If successful, the malware overwrites the master boot record (MBR) on a disk device, denoted as PhysicalDrive 0 inside Windows. Regardless of whether this action succeeds or not, the malware proceeds to create a deferred task through schtasks, in order to overload the system an hour after the initial infection.

During the propagation process, the malware enumerates all machines available to it over the network through a NetServerEnum call and then scans for the presence of an open TCP port 139. This is enough to create a list of active devices that have this port open and that can potentially be compromised.

The malware uses three possible mechanisms for reproduction:

These mechanisms are used to install and run perfc.dat for execution.

For systems that do not have the MS17-010 patch installed, EternalBlue or EternalRomance exploits are used to compromise the system. The type of exploit depends on which operating system the victim is using.

Psexec is used to run the following command (where wxyz is the IP address), using the current user's token to install the malware on the network device. Talos is still investigating the method by which the “current user's windows token” is pulled out by the malware on the current machine.

WMI is used to execute the following commands, which functionally do the same as psexec, but use the current username and password (username and password). Talos is still investigating the method by which the current user's login and password become known to the malware.

Once the system is compromised, the malware encrypts files using an RSA cipher with a 2048-bit key. Additionally, the malware attempts to clear the current system logs on the compromised system using the following commands:

Systems with a rewritten MBR after a restart show the following message:

There are several effective countermeasures that can be taken to protect your environment from Nyetya actions:

Since Nyetya is trying to overwrite the MBR on an infected machine, Talos tested the applicability of the MBRFilter software we developed to protect the system MBR. Tests have shown the applicability of this software to protect the system MBR. For those users and companies for whom this is relevant, we recommend MBRFilter as one of the protection measures. However, MBRFilter is an open source Talos project and we cannot provide any guarantees or support when using it.

Cisco customers can protect themselves from Nyetya using the following products:

The following NGIPS / Snort rules detect this threat:

The following NGIPS / Snort rules also detect malware activity in traffic:

The Threat Grid successfully detects Nyetya malware samples and correctly assigns them as malicious.

W32.Ransomware.Nyetya.Talos

027cc450ef5f8c5f653329641ec1fed91f694e0d229928963b30f6b0d7d3a745

eae9771e2eeb7ea3c6059485da39e77b8c0c369232f01334954fbac1c186c998 (password stealer)

Additional information :

What is so unique about it that distinguishes it from other malicious programs and from the same WannaCry ? Why no one writes so much about Jaff or BitKangoroo, which were distributed at the same time as WannaCry and used similar methods? Why no one makes a report and does not discuss Untukmu, Shifu, Blackshades or the same Locky , which infected more computers than WannaCry, Petya, Misha and Nyetya combined? Why do IS specialists with a serious face discuss who used to turn Petya out of them and who spread the indicators of compromise faster than anyone? Someone calls 30 minutes, someone 37 minutes, someone “woke up” only after a few hours ...

Why?

Why did Nyetya become possible at all? Why didn’t the recommendations given by almost all experts a month and a half ago when WannaCry let me go? The victims did not install the update on the operating system (at the same time, browsers with plugins could be updated)? And the external access via SMB ports is also not closed? But it was worth doing regardless of WannaCry. These are so trivial axioms of information security that they even stopped being talked about at conferences, plunging into more complex matters — machine learning, artificial intelligence, anomaly detection, big data analytics, and so on. But what can you say if even simple things that do not require any budgets are not done?

')

When WannaCry happened (as usual, all of a sudden), everyone was so immersed in it that they stopped looking around and ask a more general question: “And what needs to be done to protect yourself from cryptographers?” Not from a specific WannaCry more than 400 modifications were found), and from all (or the maximum possible number) of ransomware programs (although the same Nyetya is not an ransomware, despite the demand for ransom). After all, this is exactly the job of information security specialists - not to plug holes after they were discovered, but to reduce the area of a possible attack by building a defense system so that it can deal with most of the threats initially.

How to build a protection strategy against encryption programs?

Is it possible to catch not a specific version of a specific cryptographer, but to develop a universal option? Let's try. Without pretending to complete coverage, let’s make a list of the characteristics of most cryptographers:

- hitting the computer through various communication channels (mail, Web, flash drives, shared folders, direct network connection)

- interaction with the command server (according to our statistics in 92% of cases using the DNS protocol) or checking for an external kill switch

- work with the file system, including the substitution or deletion of individual files, as well as a large number of operations with files of certain types

- work with the registry

- work with administrative utilities

- interaction with the anonymous network Thor

- further propagation by scanning vulnerable nodes inside or outside the network.

It is clear that not all of these characteristics are present in every cryptographer. For example, the self-distribution function was not so often used by attackers, who, preferring point attacks, forced users to perform some action (click on a link, open an attachment, run a file from a flash drive, etc.). Not all cryptographers had the opportunity to work with the command server, acting completely autonomously. But without having one or two characteristics, the rest were still present and they could be countered with a set of protective measures. What could be the measures of protection?

Again, let's reason. In the threat prevention phase, we must:

- block unnecessary network and DNS connections with the outside world, including anonymous networks (Top, etc.)

- segment the network to prevent the spread of malicious code, if it did get into the internal network, for example, on a flash drive

- fix vulnerabilities

- block the use of vulnerabilities if they cannot be eliminated (note, I’m not talking about blocking specific exploits, but blocking attempts to exploit specific vulnerabilities, which allows blocking any existing and future exploits - this distinguishes traditional IPS from modern NGIPS)

- block user access to malicious IP addresses, domains and URLs, including from mobile devices

- block the launch and operation of dangerous applications and processes

- block the spread of malware over the network (both at the perimeter and inside the LAN)

- Implement (pre-tested recovery capability) backup system.

Model of information security “BEFORE IN TIME - AFTER”

But today one cannot be sure of 100% threat prevention - they can get on a flash drive, via a 4G modem, unprotected Wi-Fi or a company top manager who infected his personal laptop at home and brought it to the corporate network for treatment could bring them . Therefore, several years ago we suggested following the BEFORE - DURING - AFTER concept, which implies that we should spend 80% of efforts to neutralize threats, but usually allocate a third of possible resources and protective measures. Another third to put on the discovery of what can pass through protective barriers. In the discovery phase, we must:

- identify the use of known vulnerabilities (including attempts to use holes)

- detect abnormal, atypical user behavior (for example, starting psexec for an ordinary company user), nodes (for example, network scanning), applications (for example, encapsulating something non-standard in HTTP traffic), processes (for example, injection) and network traffic ( for example, bursts of traffic of a certain type, different from the normal picture on the network)

- analyze on the fly attachments to e-mail and files downloaded from web pages, running scripts or displayed Flash or other multimedia clips and banners

- Detect calls to the kill switch or other sites of the attacker's infrastructure on the Internet (for example, to DGA domains) by analyzing DNS queries, proxy Web logs, Netflow analysis, and simply learning TCP / IP streams.

And what about the remaining third effort? We must let them in to remedy the situation, which is unpleasant to admit, but which is possible in any company - to fight the infection or compromise that has happened. But in this case we should not bury our heads in the sand like ostriches (in fact, ostriches do not bury their heads in the ground, but such a version has gone since the times of Pliny the Elder and we are used to it), and promptly localize the problem and prevent it from spreading network, “cure” the compromised nodes and return the system to its preattached state. In the response phase, we must:

- limit network traffic from infected or suspicious sites

- put suspected or infected nodes in quarantine (by placing in the appropriate VLAN or blocking the port on the switch or changing the ACL on an access point or router), and user accounts temporarily freeze

- to analyze suspicious files in the sandbox, as well as using other mechanisms

- track the trajectory of malicious or suspicious files on the network

- restore data from backup

- launch in some cases complex processes of Threat Hunting, which allow to confirm or refute the hypothesis about the presence of a cryptographer, put forward by the information security analyst.

Cisco solutions for dealing with cryptographers

It is clear that one product does not implement the above set of tasks. Modern extortionists are still quite complex and use a variety of attack vectors so that they can withstand any one product, even the best, hung with awards and placed in various magic squares. For example, Cisco, which is the leader of the global information security market, has a whole range of technologies and solutions that can deal with this threat, at different stages of the cryptographer's life cycle, from an infection attempt to active distribution on the internal network.

But this is not just a beautiful picture. We have prepared (by the way, even before WannaCry and Nyetya) detailed technical guidelines on the design of the infrastructure to combat this threat. It was developed by us in accordance with our Cisco SAFE (Security Architecture for Enterprise) architecture, but it also examines in detail the methods of penetration of ransomware programs into the customer’s network, and methods of preventing, detecting and responding to the current life cycle of the modern threat “ TILL TIME” AFTER “.

This manual describes the whole stack of technologies that allow you to deal with extortionate software:

- Cisco ASA and Cisco Firepower hardware and virtual firewalls

- Cisco NGIPS and Cisco wIPS Intrusion Prevention Systems

- anti-malware systems Cisco Advanced Malware Protection

- Cisco OpenDNS DNS Monitoring Tools

- Cisco Identity Service Engine corporate network segmentation tools

- systems analysis of anomalies in the internal network of enterprise Cisco Stealthwatch

- hardware, virtual or cloud access control of Cisco Web Security web resources

- Cisco Email Security inbound and outbound hardware, virtual, or cloud protection

- Cisco AMP ThreatGrid sandbox

- etc.

But Cisco would not be Cisco if it simply listed the technologies and solutions used in the flyer. We have combined them into a complete system, which allows us to obtain a synergistic effect from this integration. Each technology, each product found its place, most accurately satisfying the task. Our customers do not need to think about what and how to do to protect against the most serious threat of recent times, on which attackers earn more than $ 1 billion a year. We have tested the work of all components of the new leadership and are responsible for their performance.

But what about all the same to be with NePety?

If you still go back to the story with Nyetya (aka Petya.A, aka Petya.C, aka PetrWrap, aka PetyaCry, aka GoldenEye, aka ExPetr), what do we know today?

Starting with SamSam, the main victim of which was the US health authorities in March 2016, Talos warned of the risk of malware propagation using unsecured network-wide vulnerabilities. In May 2017, WannaCry made many cry, taking advantage of the vulnerabilities of the SMBv1 protocol implementation and spread widely across many systems around the world. On June 27, a new malware sample was found, quite different from the original Petya, so that people began to give it new names, such as Petrwrap and GoldenEye. Talos identifies this pattern of malware as Nyetya. Our current investigation (the original and constantly updated Cisco Talos blog entry in English is available here ) showed that this sample also uses EternalBlue and EternalRomance in combination with psexec and WMI tools to spread and infect new victims within the network. We will look at this in detail below in the “Nyetya malware functionality” section. Compared to WannaCry, there is no scanning external network component.

Identification of the initial vector is currently difficult. Early reports on the use of the mail vector have not yet been confirmed. Based on observations of the behavior of the samples “in the wild world”, we see that there are no obvious, visible external mechanisms for the reproduction of this sample of malware. We suspect that part of the infections may have used a mechanism for updating accounting software known in Ukraine, called MeDoc, which is indirectly confirmed by the manufacturer MeDoc and research colleagues. Talos continues to search for the original attack vector.

As with any malware, Talos does not recommend paying a ransom. Keep in mind that for this particular sample of malicious code it is also meaningless, since the mailbox that was supposed to be used to exchange information about payments and get the decryption keys was blocked by the mail provider posteo.de. It was the only way of communication used by attackers to obtain information about payments and to obtain decryption keys. There are no other methods for connecting malware to remote management servers and retrieving decryption keys from them (in the absence of such). Thus, Nyetya is not a cryptographer who works for ransom, but is simply a sample of malware that destroys data and systems that can reach.

Method for obtaining user passwords

Perfc.dat, responsible for spreading the malware, contains an embedded executable in the resources section. This executable is created as a temporary file in the user% TEMP% directory and starts the named pipe with a parameter containing the GUID. Further, the main executable module Perfc.dat interacts with this executable module through the named pipe. For example:

C:\WINDOWS\TEMP\561D.tmp, \\.\pipe\{C1F0BF2D-8C17-4550-AF5A-65A22C61739C} It seems that .tmp-executable code is based on Mimikatz, a well-known open source toolkit for retrieving user passwords and logins from the system’s memory and uses several methods to do this. However, Talos confirms that this code is not an exact copy of Mimikatz.

The received login / password pairs are used to infect remote systems via WMIC and PsExec. For example:

Wbem\wmic.exe /node:"wxyz" /user:"username" /password:"password" "process call create "C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe \"C:\Windows\perfc.dat\" #1 Nyetya malware functionality

In its investigation, the Talos team discovered that the compromised systems had the file “Perfc.dat”. Perfc.dat contains the functionality necessary to further compromise the system, and contains one unnamed exported function, # 1. The library attempts to obtain system administrator privileges using calls to SeShutdowPrivilege and SeDebugPrivilege on behalf of the current user through a call to the Windows API AdjustTokenPrivileges. If successful, the malware overwrites the master boot record (MBR) on a disk device, denoted as PhysicalDrive 0 inside Windows. Regardless of whether this action succeeds or not, the malware proceeds to create a deferred task through schtasks, in order to overload the system an hour after the initial infection.

During the propagation process, the malware enumerates all machines available to it over the network through a NetServerEnum call and then scans for the presence of an open TCP port 139. This is enough to create a list of active devices that have this port open and that can potentially be compromised.

The malware uses three possible mechanisms for reproduction:

- EternalBlue is the same exploit as WannaCry.

- EternalRomance - SMBv1 exploit, made available as a result of a ShadowBrokers leak

- Psexec is a legal tool for Windows administrators.

- WMI - Windows Management Instrumentation, a legal component of Microsoft Windows.

These mechanisms are used to install and run perfc.dat for execution.

For systems that do not have the MS17-010 patch installed, EternalBlue or EternalRomance exploits are used to compromise the system. The type of exploit depends on which operating system the victim is using.

- EternalBlue

- Windows Server 2008 R2

- Windows Server 2008

- Windows 7

- EternalRomance

- Windows xp

- Windows Server 2003

- Windows vista

Psexec is used to run the following command (where wxyz is the IP address), using the current user's token to install the malware on the network device. Talos is still investigating the method by which the “current user's windows token” is pulled out by the malware on the current machine.

C:\WINDOWS\dllhost.dat \\wxyz -accepteula -s -d C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe C:\Windows\perfc.dat,#1 WMI is used to execute the following commands, which functionally do the same as psexec, but use the current username and password (username and password). Talos is still investigating the method by which the current user's login and password become known to the malware.

Wbem\wmic.exe /node:"wxyz" /user:"username" /password:"password" "process call create "C:\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe \"C:\Windows\perfc.dat\" #1" Once the system is compromised, the malware encrypts files using an RSA cipher with a 2048-bit key. Additionally, the malware attempts to clear the current system logs on the compromised system using the following commands:

wevtutil cl Setup & wevtutil cl System & wevtutil cl Security & wevtutil cl Application & fsutil usn deletejournal /D %c: Systems with a rewritten MBR after a restart show the following message:

Recommended countermeasures

There are several effective countermeasures that can be taken to protect your environment from Nyetya actions:

- First and foremost, we highly recommend customers who have not yet installed the patch MS17-010 to do so immediately. Given the scale of the threat and its spread, it is extremely unwise to have unpatched systems.

- Use software that can detect and block the launch of known samples of malicious code.

- Develop and implement an action plan in the event of such abnormal situations, including not only regular backups, but also regular checks of data recovery from backups. Backups should not be accessible from the network and stored separately.

- Completely disable SMBv1, if possible, and switch to using more advanced SMB versions. (SMBv2 first appeared in Microsoft Vista).

Since Nyetya is trying to overwrite the MBR on an infected machine, Talos tested the applicability of the MBRFilter software we developed to protect the system MBR. Tests have shown the applicability of this software to protect the system MBR. For those users and companies for whom this is relevant, we recommend MBRFilter as one of the protection measures. However, MBRFilter is an open source Talos project and we cannot provide any guarantees or support when using it.

Current Cisco Security Coverage

Cisco customers can protect themselves from Nyetya using the following products:

- Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideal for blocking the execution of malware. It should be noted that the detection of malicious code is carried out not by signatures, but by behavior, that is, AMP does not depend on the frequency of updating antivirus databases, like traditional antiviruses.

- Network protection devices such as NGFW, NGIPS, and Meraki MX can detect network activity associated with a threat. It is worth noting that we have discovered the exploitation of EternalBlue and EternalRomance since April of this year, long before the start of the WannaCry and Nyetya epidemics.

- The AMP Threat Grid successfully identifies malware binaries.

- Email and Web are not yet confirmed as currently used in the attack vector. In addition, there are no known external control elements for this malware at this time.

- Fresh Snort signatures are available on the official website of the Snort.org project.

NGIPS / Snort Rules

The following NGIPS / Snort rules detect this threat:

- 42944 - OS-WINDOWS Microsoft Windows SMB remote code execution attempt

- 42340 - OS-WINDOWS Microsoft Windows SMB anonymous session IPC share access attempt

- 41984 - OS-WINDOWS Microsoft Windows SMBv1 identical MID and FID type confusion attempt

The following NGIPS / Snort rules also detect malware activity in traffic:

- 5718 - OS-WINDOWS Microsoft Windows SMB-DS Trans unicode Max Param / Count OS-WINDOWS attempt

- 1917 - INDICATOR-SCAN UPnP service discover attempt

- 5730 - OS-WINDOWS Microsoft Windows SMB-DS Trans Max Param OS-WINDOWS attempt

- 26385 - FILE-EXECUTABLE Microsoft Windows executable file save include SMB share attempt

- 43370 - NETBIOS DCERPC possible wmi remote process launch

Threat grid

The Threat Grid successfully detects Nyetya malware samples and correctly assigns them as malicious.

Compromise Indicators (IOCs)

Detection in AMP

W32.Ransomware.Nyetya.Talos

SHA256

027cc450ef5f8c5f653329641ec1fed91f694e0d229928963b30f6b0d7d3a745

eae9771e2eeb7ea3c6059485da39e77b8c0c369232f01334954fbac1c186c998 (password stealer)

Additional information :

- Cisco Webinar video recording "Do not let me encrypt myself" about the WannaCry encryption program

- Cisco Infrastructure Design Guide for Extinguishing Extortionists (in English)

- a section on the Cisco website (in English) devoted to the fight against extortionists

- Cisco recommendations to combat WannaCry (in Russian)

- Detailed description of network segmentation capabilities (in Russian)

- Annual Cyber Security Report (in Russian)

- Detailed and regularly updated description of Cisco Talos Nyetya (in English)

- e-book " Ransomware Defense for Dummies " (in English)

- video presentation on our approach in combating extortion programs (in Russian)

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/331990/

All Articles