How to ensure that learning in games is not annoying

When I write articles about learning in video games, violent discussions always start around them. People inevitably begin to list all the unsuccessful fragments of training, clumsy techniques and failed experiments as examples of the fact that “learning is bad, it would be better if it didn’t exist at all!”.

If you search the site tvtropes.org (this is a database of clichés of pop culture) the word "tutorial", then there are more than ten different trails related to the fact that people hate in the process of learning video games. For comparison: I found only two discussions of how much users hate downloadable content.

')

The saddest thing about this is that when I write about training, I mean not such training.

Because of this misconception, I cannot report on learning what I want.

When I talk about training in video games, I strive to reduce everything to a very simple idea, which, I think, is perfectly implemented in the best games: if you create a very clever level design, you can train players simply ... by letting them play.

I hope to show that this is not a particularly new or revolutionary perspective on learning. With proper implementation, the designer wants the player not to even notice that learning is already happening. That is why such examples are usually not discussed.

However, with poor implementation, learning can be one of the worst moments of the game.

RTFM?

Before proceeding, I must mention one of the oldest ways to teach games: a guide. If you are young, you may not remember these small paper brochures that came bundled with a video game. These pamphlets contained pictures, warnings about the danger of epileptic seizures and (probably the most important) an explanation of how to play the game.

Manuals are a pretty good way to educate users about the game, but they have obvious drawbacks:

- They assume the ability to read, which is not suitable for games of different types and designed for different audiences.

- They are easy to lose (or do not forget to give at resale), while the players are left without any training.

- They may fall victim to the same problems as in-game training. I will review these issues a little later.

- They significantly increase the interval between the time of purchase and the time of the start of the game. This is undesirable, whether the manual is in paper or in software.

Because of these and other shortcomings of the booklet guides, game designers started trying to build training directly into the game. Some succeeded better than others.

Why do games need training at all?

Common to all games is that they all have rules. The rules define the boundaries of the game, the principles of scoring, the conditions of completion, the way players interact with the game and with each other. If you put together a company for playing hide-and-seek, you must first explain who will drive, where, according to the rules, you can hide, how long the driver thinks, and so on.

If two players sit at the chessboard, the game will not start until both players know how the pieces move and what are the conditions for victory. (And is the “take on pass” rule applicable.)

It all comes down to the following: the game designer (child explaining the rules) must somehow convey the rules to the players (other children).

If the first child (game designer) cannot explain the rules, the game will not take place. The first child must teach the rest.

If the player does not know how to play, then he will not be able to play.

Why do many people think they hate learning in video games?

The trail laid by the designers of the old games is littered with the bodies of failed learning experiments. Knowing that players absolutely need to know the rules of the game, many go too far and learning begins to annoy.

Here are some of the common (and absolutely fair) reasons for hate learning:

“Learning is wasting a player’s time!”

Players usually recall incredibly long training levels (some lasted longer than six hours), or mandatory stages with a shooting gallery at the beginning of each first-person shooter. This is a very annoying idea, so hatred is quite understandable here, but by “learning” I mean something else.

“Training is imposed on the player!”

After this complaint, there is usually a long list of unsolicited and incredibly annoying “hints” that need to be passed before you are allowed to play. This approach is inelegant and not very friendly to the player. And this is also not the kind of “training” I am talking about.

“Tutorials are a bunch!”

This exclamation is followed by a list of required tutorials that “lead the player’s hand” and do not allow him to learn something independently, explore the world outlined by the rules of the game, and just learn how to play the game! With the second pass, it's usually even worse - you already know all this nonsense, and just want to get to the game! But this is not the kind of training I’m talking about.

"Learning is insulting!"

This usually refers to the nonsense about "whether you want to switch to easy mode." The tone of such training is too condescending, it seems that it implies that the player is not a reasonable human being capable of thinking and research. Another frequent case is the text that appears after you have done some action several times. For example, the fiftieth repetition of "Press A to jump!".

But I will talk about something else.

Oh, shooting shooting, where heroes are not born, but become!

“Learning is unacceptable aesthetically!”

Sometimes it is really unacceptable, for example, when your character is a powerful superhero, spewing hundreds of bullets, and you are taught how to direct a weapon at a target and shoot. Sometimes it is less obvious, and only slows down the game, destroying the feeling of flow in that part of the game in which the pace should accelerate (ie, at the first level).

No, that's not what I'm going to talk about.

“Learning almost never works!”

This complaint usually refers to the type of tutorials "we will quickly show the management screen and you will never see it again." Sometimes the game teaches something at the first level, but does not use this knowledge, and by the time of its use the player already forgets about it.

“How is a long jump made there?”

As you probably already guessed, I will not talk about it either.

“I love to explore everything on my own. I like the games that give me the most to do anything. ”

This sense of learning and space for experimentation is the end result of what I said about learning. If you create levels (or content) without forgetting about learning, you train players by simply letting them play the game.

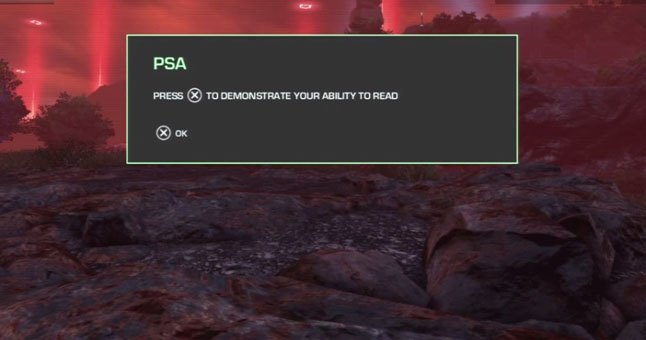

"Are you sure you have a brain?" Click X to confirm. ” (Parody of Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon tutorial.)

The most famous example

I want to talk about the famous example of learning "inside the gameplay": about the first two screens of the original Super Mario Bros. for NES.

In one episode of Iwata Asks, Nintendo CTO Satoru Iwata talks with Super Mario Bros. designer . Shigeru Miyamoto (Shigeru Miyamoto) about this first screen and about all the "hidden" training built into this deceptively simple design:

About gumbus (goomba):

Iwata : If you are playing for the first time, without having any knowledge about the game, you will come across the first gumba and die.

Miyamoto : Yes, and so we needed to naturally train the player ... so that he jumped over and avoided them.

Iwata : Then, when you try to avoid them, it will sometimes happen that the player makes a mistake and accidentally falls on the gumba from above. Thus, in the course of the game, he learns that you can beat them by jumping on their heads.

About bonus mushrooms:

Miyamoto : ... When you play, you see the gumba right from the start, and it looks like a mushroom. When you hit the box and something like a gumba flies out of it ...

Iwata : You're running away.

Miyamoto : Right, running away. This has become a serious problem for us. We needed to somehow make it clear to the player that this is actually something good.

Iwata : If a player avoids the first gumba, and then jumps up and hits a box above his head, a mushroom will jump out of it and the player will be surprised. But then he will see that the mushroom crawls to the right and thinks that it is safe. “Something strange appeared, but everything is fine with me!” But then, of course, after hitting the pipe, the mushroom would come back! (laughs)

Miyamoto : That's right! (laughs)

Iwata : At this point, even if the player panics and tries to jump from his path, he will hit the box. And at that second when he realizes that he is finished, Mario suddenly shakes and grows in size! Maybe the player will not understand at first what happened, but at least he has not lost his life.

On these two screens, the player, according to Miyamoto, "naturally learns" most of the important skills needed to play.

For example, Mario starts the game from the left side of the screen. The entire screen is empty, and the player can safely experiment with the controls. When the player presses A, Mario jumps on the spot. By clicking on the cross, the player learns to run to the right (Mario can run to the left, but the camera will not scroll the screen in this direction).

The entire first screen is designed to give players their own control. The entire second screen is devoted to getting acquainted with other game mechanics that are difficult to understand (for example, that the bonus looks like an enemy) and makes it easy to learn, research.

There is a chance that the player will miss all this for the first time, but since after each death the level begins anew, it must be passed again and again. Gradually, the training will work and the player will “open” these almost hidden rules.

Examples from mobile games

Pudding monsters

One of my favorite examples of mobile learning games is Pudding Monsters . The first set of levels is dedicated to learning the basics of the game. Below I give an image of the first three levels of Pudding Monsters with a description of what the player must learn in each puzzle:

Level 1

At level 1, a player learns how to move a monster to another monster. If the player sends the monster in any other direction, he will fly away from the screen and the puzzle will start anew. Players also learn that when they join monsters, they turn into a single, larger new monster.

Level 2

At level 2, players learn that there are other, fixed parts of the level that pudding monsters may encounter. This scheme allows you to perform turns. The level also teaches that sometimes the monster needs to be moved several times to solve the puzzle. In addition, the player can solve the puzzle in several ways (by moving the upper monster or the lower one).

Level 3

Taking what the player has learned on the previous two levels, the game teaches him that when the puzzle can be solved in several ways, the designers place tiles with stars on the ground. If a player completes a puzzle, when monsters are on all the stars, then he gets bonus points. Note that at this level there are ways to close two or three stars.

Cut the rope

Cut the Rope has more text than Pudding Monsters , but you can see how the complexity of level design increases and the player is taught basic skills one at a time (the red arrows and text are added by me).

Level 1

Level 1 teaches the player how to achieve victory - namely, you need to feed two candies of monsters (one each), cutting off the ropes holding them. Also in this level, the idea of stars is introduced for good passage.

Level 2

With the exception of falling candies, the first level does not show the player any physics, so he may not be aware that candies can swing on the ropes. This puzzle teaches the player the physics of rocking candies and the influence of several ropes.

Players also need to learn that you can lose in a puzzle (for this you need to restart the puzzle again). This is the first puzzle in which you can lose (if you first cut off the top left or bottom rope).

Level 3

At this level, many losing opportunities are added, but there is still the only way to win. First of all, this level teaches how candies can collide with each other and repel other candies. In the first levels it is very difficult not to get three stars. Gradually, complications are introduced into the game, which make it difficult to pass to obtain all the stars. In addition, there are various solutions.

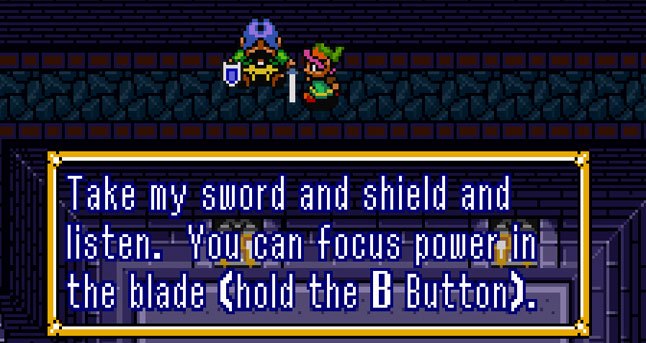

One of my favorite examples

One of my favorite examples from the history of games is taken from the game for the Super Nintendo. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past .

The first two rooms of the Eastern Palace, the first dungeon of the game, became my favorite parts of the training throughout the game.

By the time the player reaches the Eastern Palace, the game of learning moves from pushing the player to stimulate research. Since the player at this moment knows all the basic actions, mysterious changes in management happen much less frequently, so text prompts are not needed for them.

When designers introduce new puzzle elements in a new dungeon, the player must learn how to interact with these elements in order to solve more complex and intricate puzzles in the future.

By this time, the player had learned three ways to open the door: finding a key, killing enemies, or using a lever. In many puzzles of the Eastern Palace, two new ways of opening doors are used: hidden and visible buttons on the floor.

The concept of the puzzle is simple - the player needs to find a button on the floor and put Link on it to open the door. But if the players do not know what the button looks like, then the puzzle gets confused very quickly and its solution becomes random.

A simple (lazy and inelegant) way to teach a player is to close him in a room with a button on the floor and exit. When a player leaves the room, close the player in a new room with a button hidden under the pot and another exit. When a player passes through these two rooms, the designer can assume that the player already knows everything needed to pass.

In this case (the first room of the dungeon), I understand why the designers did not want to close the player. In case the player decides not to go to the dungeon, the designers wanted to leave him the opportunity to go out, wander around the world and look for improvements, and then go back when the player is ready to explore the dungeon.

In addition, the game has a lot of hidden areas consisting of one room that can not be passed without having a certain object. A dungeon with an open door and no obvious ways to go further can look very much like one of these hidden rooms. Therefore, players can give up and go look for the Eastern Palace somewhere else.

A button on the floor under the center pot opens the central door. Open corridors on both sides report that the central door is the way forward.

The solution found by designers eliminates all these potential problems. In the picture above, the player enters the room below. The middle door is closed, it can be opened with a button hidden under a brown pot in the middle. The doors on the left and right are open and lead to the second screen.

If a player passes through one of these doors, he sees that the only way forward is possible only through the platform in the center. If it were not there, the player could enter the room, run a little along it (thinking that he is in the above-mentioned one room, which requires an object to pass through, and not seeing any solutions that allow opening the door).

The ability to see the way forward implies that the solution to the puzzle must be in the first room.

In the second room, the player must step on the visible button on the floor to open the next door. Since this is not as interesting as searching for a hidden button, the player must also deal with the enemies in this room.

Afterword

I don't think anyone makes learning intentionally bad. I don’t think that designers want some part of the game to annoy the player, not to mention the part that is most important for understanding and enjoying the gameplay.

However, sometimes, when the game has to be released, and the deadline is tight, we have to add an overtly weak tutorial, an obviously annoying text hint or something equally inelegant simply because there is not enough time. This happens even with the best of us, and I'm not sure that in some game (except, perhaps, Super Metroid ) we coped with it perfectly. I know that this did not work in any game I created, no matter how hard we try.

Sometimes, despite the enormous efforts, the elegant design of the levels created by us as learning did not work, and we had to add something of lower quality at the last minute.

But if you like games that leave you alone and allow you to study everything yourself, then this type of training will delight you both as a player and as a game developer. Many games cope with this, to one degree or another, and when this happens, the effect is very powerful.

Knowing this and working on it, you can develop a much more productive attitude than a simple “learning is sucks.”

You learn (and teach others) to play the way your friend tried to play hide and seek in the yard: during the game, according to one rule at a time.

Additional reading

- If you want to learn a really detailed analysis of how this way of training players worked in one of the greatest games, I recommend reading the excellent article by Hugo Bille The Invisible Hand of Super Metroid .

- Josh Bycer (Josh Bycer) wrote a post about what he called "organic design" , and I'm sure he says the same thing.

- I wrote another article about tempo and archetypes, which explains some useful tricks for creating this type of training (namely, my ABC trick from the article by reference). By introducing mechanics at the right speed, you naturally get the benefits of this type of training.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/330948/

All Articles