What determines the interesting gameplay?

I think everyone will agree that the feelings of the gameplay in different games are different. Some games seem more "game" than others. Just compare the Super Mario game with something like Dear Esther, and it seems to me that it’s clear that the first one feels like more gameplay than the last one. What caused this feeling? My hypothesis is: the difference in planning capabilities .

The more a player can plan in the game in advance, the more exciting it seems.

')

Before I present evidence that this is most likely true, I need to give some background information. To understand why planning plays such a prominent role in games, we need to look at the evolution of our species and answer the question: why are the fish so stupid?

Here is how the world usually looks for fish:

They can see only 1-2 meters in front of them, and often the situation is even worse. This means that fish cannot make distant plans. They simply react to what appears before their eyes, this is their whole life. If fish life was a game, it would be a limited version of Guitar Hero with random noise instead of music. This is exactly how fishing happens. Fishes do not think, as we do, they are controlled by reactions with rigidly defined logic.

Most of the history of the earth was such a life of organisms. But after this, about 400 million years of evolution passed. Fish began to move to land. Suddenly, the following picture appeared to their eyes:

It changed their world. Suddenly, it became possible to plan and correctly perceive your environment. Previously, the smart brain was a waste of energy, but now it has become a great advantage. In fact, this transition was so important that it probably became a significant factor in the evolution of consciousness. Malcolm MacIver, who, as I know, was the author of this theory, writes about it like this :

“But then, about 350 million years ago, in the Devonian period, such animals as tiktaalik began to make the first trial raids on the land. In terms of perception, it was a completely new world. We can see objects about ten thousand times better. Therefore, simply by sticking their eyes out of the water, our ancestors fell from the muddy mist of the former environment into a clearly visible world, where they could survey the environment from a fairly considerable distance.

This put such first members of the club "clearly seeing" in a very interesting position from the point of view of evolutionary perspectives. Think of the first animal that received any mutation that separates its sensory input signals from motor reactions (until that moment their instant connection was necessary, because reactivity was required not to become someone's dinner). At this stage, they could potentially observe several possible options for the future and choose the one that is most likely to lead to success. For example, instead of rushing straight to the ghazal, risking to reveal its location too early, you can slowly sneak along the line of bushes (knowing that your future dinner also sees ten thousand times better than its ancestor who lived in the water) until you get closer. "

You can demonstrate the above using the following example:

This image beautifully shows the conceptual difference in the processes involved. In one, a linear process is used, in which reactions occur along the course of an action. In another, the animal explores the terrain in front of itself, examines various approaches and selects the one that, with the available data, seems to be the best.

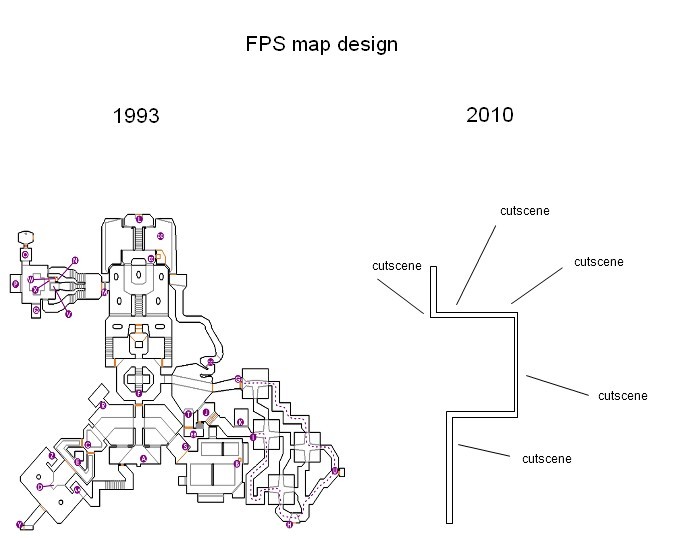

The analogy is not complete, but there is a striking similarity with the following image, showing the difference between the design of old school and more modern FPS:

I know that this comparison is not entirely honest, but what is important here is that when we look at these two images, it is obvious to us which of these two designs has better gameplay. The image on the left represents a more complex and interesting environment, and on the right a linear sequence of events. And just as the world of fish correlates with the world of land animals, it means a huge difference in planning capabilities.

There are other interesting links between the ability to see and plan. Malcolm McIver answers the question about the intelligence of octopuses:

“It's amazing how these unprotected pieces of tasty protein survived in the face of millions of years of constant threat. They have, by the way, the largest of all known types of eyes (for the largest deep-water species, the size reaches the diameter of a basketball). Obviously, they use them to recognize very distant whale silhouettes (their greatest enemies), in the light reflected from the surface.

The theory develops the idea that the advantage of planning is proportional to the limit, in which the creature can sense, to the distance of movement during the reaction. The theory determines the period of our evolutionary past, in which there was a large-scale change in this ratio, and assumes that such a change has become an important factor in the development of planning ability. Interestingly, octopuses and bryzguny usually motionless before performing their actions. This maximizes their relatively small area of sensory perception. In other words, for animals caught in a water mist trap, thanks to planning, there are other ways to increase the area of perception relative to the distance they move. ”

Vision, of course, is not the only reason that we humans have evolved to the current level of intelligence and consciousness. The other important factors were the upright walking and our universal arms. Having risen to our feet, we were able to see better and more efficiently use our hands. Hands are our main means of changing the world around us. They allowed us to create tools and a different way to change the environment to optimize survival. All these factors are inextricably linked with the possibility of planning. After we learned to change the world around us, the number of available options expanded and the complexity of our plans increased to a great extent.

But that was not the end of it. Planning is a crucial part of our social life. The model of a person’s mental state , our ability to imitate other people, is both the cause and the result of our planning ability. Managing social groups has always been a very thorough process of thinking through various options for action and their consequences.

In addition, planning also underlies the other two phenomena that were discussed in my blog earlier: mental models and effect of presence . We have mental models in order for us to evaluate actions before they take place, which is obviously crucial for planning. Presence is a phenomenon that occurs when we are included in our plans. We want to model what is happening not only in the world, but also with ourselves.

To summarize: there are many evolutionary reasons why planning became the fundamental basis of what made us human. It is a big part of who we are, and when we can take advantage of these abilities, we certainly find it exciting and interesting.

Well, all this background information is very informative, but is there really reliable evidence that this is applicable in games? Yes, and in fact, quite serious! Let's look at what I find most interesting.

There is a player enthusiasm model called PENS (Player Experience of Need Satisfaction), and it is rather rigorously investigated. To assess what the player thinks about the game, she uses the following criteria.

- Competence . How well the game satisfies our need for a sense of competence, a sense of mastering the game.

- Independence What level of freedom does a player have and what opportunities does he have for expressing it?

- The bondage How strongly satisfied is the player's desire in common with other players?

Measuring how well a game manifests itself in these metrics turned out to be a much better indicator of various aspects of success (sales, probability of recommendations of the game by people, etc.) than a simple survey on whether the game is “interesting.”

And, more importantly, two of the above factors are directly related to planning. Competence and independence are very tied to the ability of the player to plan. Let's explore why this is so.

In order for the player to feel competent in the game, he must have a deep understanding of how the game works. Of course, there are games in which fairly simple reflexes, but they are always very primitive. Even in most music games, the player needs to learn and understand in order to play better. An important part is also the memorization of the melodies of each level. Why? For the optimal location of the “manipulators” of the input (whether it be toes or feet), to get into as many notes as possible. All these aspects boil down to one thing: the ability to predict the future.

We see the same thing in most games. The player begins to play better in Dark Souls, when he understands how monsters attack, what is the level scheme and how his own attacks operate. Learning the work of the world and gaining the ability to predict is the cornerstone of competence. Of course, the player needs to develop motor skills to perform the necessary actions, but this is almost always less important than understanding when and why actions are needed. A simple prediction ability is not enough, you also need to have a sense of what goal the player wants to achieve, and use the prediction ability to perform the steps required to achieve it. Or, in other words: the player needs to plan.

Independence also depends heavily on the ability to plan. Imagine a game in which you have a large degree of freedom, but you absolutely do not understand how the game works. Anyone who has launched a complex strategy game without an understanding of the basics knows that this is not very exciting. For freedom to mean something, you need to have an idea of what to do with it. You need to understand how the game mechanic behaves, what tools are at your disposal, what goals you want to achieve. Without this, freedom is confusing and meaningless.

To ensure a sense of independence, the game must not only provide a large space of opportunity, but also teach the player how the world works and what is the role of the player. The player must be able to model in mind the various actions that can occur, and come up with the consequences that can be used to achieve a certain goal. When you have these opportunities, then you have the freedom that is worth having. It's probably pretty obvious that I am again talking about the ability to plan. A world in which a player cannot plan is a world with little independence.

Similarly, if there is only a linear sequence of events in the game, there is not so much planning left. For a player to make plans, he must have choices. This does not apply to cases where only a certain chain of actions is possible. Such cases are a typical example of lack of freedom, and they do not satisfy the player in terms of freedom. I repeat - planning and independence are connected in very convoluted ways.

You can also prove that the connectedness factor also correlates with planning. As I explained above, any social interaction is highly dependent on our ability to plan. However, I do not think that dependence is not so strict, and the first two aspects are quite enough. So let's better look at the evidence from a different angle.

In games, there is a long-term trend - the addition of new "meta" functions. Such a very common function today is crafting, and in most major games it is present to some extent. RPG-like elements of leveling are also widely used, not only for characters, but also for weapons resources. Another common collection of money that can be used to buy various items. Look at almost any recent game and you will definitely find at least one of these functions.

So why are they added to the games? The answer is quite simple: they make the game more exciting. Why this happens - the question is a bit more complicated. This can not be only because it gives the player more options. If this were the case, games with random variations of mini-games would appear, giving spice to the game process. But instead we see constantly used strictly defined types of functions.

My theory is that it is related to planning. The main reason for adding such functions is that they expand planning space and provide more tools that can be included in planning. For example, collecting money in combination with the presence of the store means that the player will have a goal - the purchase of a certain item. Collecting the right amount of money with the intention to exchange it for goods is a plan. If the desired subject and method of collecting coins are connected to the main gameplay cycle, then this meta-function will give the feeling that there is more planning in the main cycle than it actually is.

These additional features can also add some severity to ordinary gameplay. Remember how to think about what weapon to use in The Last of Us. The player has a garbage from which you can craft items, and all these items allow you to use different tactics in battle. And since it is impossible to apply them all at the same time, the player needs to make a choice. Making such a decision is always creating a plan, so the feeling of involvement in the game increases.

Whatever your attitude to these kinds of meta-functions, one thing is certain: they work. Because if they did not work, then their popularity would not grow and would not be maintained for so long. Of course, you can create a game with a large amount of planning and without using these functions. But it will be a more difficult path. Adding these features is a well-proven way to increase engagement, so their use is very tempting, especially if, in their absence, you can lose to competitors.

And finally, I want to talk about what actually led me to thinking about planning. It began with the fact that I began to compare SOMA with Amnesia: The Dark Descent. When creating SOMA, it was very important for us to add as many interesting features as possible, and we wanted the player to have many different activities. I think it would be fair to say that SOMA has a wider range of interactions and greater variability than Amnesia: The Dark Descent. But despite this, many people complained that SOMA was too much like a “walking simulator”. I can not recall a single similar comment about Amnesia. Why did this happen?

At first I could not understand this, but then I highlighted the main differences between these games:

- The state of mind system in Amnesia.

- Lighting / health resource management.

- Puzzles distributed over different levels.

All of these aspects are directly related to the player’s ability to plan. The mental health system means that the player has to think about which routes to take, whether to look at monsters, and so on. Such moments the player needs to consider when moving through the level and they provide a constant need for creating plans.

The resource management system works in a similar way: the player also needs to think about when and where to use the resources available to him. It also adds another layer, because it becomes clearer to the player what types of objects he will find on the map. When a player enters the room and pulls out the drawers, these are not just useless actions. The player knows that some of the boxes have useful things, and searching the rooms becomes part of a larger plan.

In Amnesia, the design of many levels is built around a large puzzle (for example, the launch of an elevator), which is decided by performing a set of level-scattered and often interrelated puzzles. Due to the scattering of puzzles in the rooms, the player needs to make a decision about where to go next. It’s impossible to complete the game simply by using the “visit all rooms” algorithm. You need to think about which parts of the level you need to return to, and what puzzles are left to solve. It is not very difficult, but enough to create a sense of planning.

SOMA does not have any of these functions, and none of the new features compensate for the lack of planning. This means that the game as a whole creates a feeling of a lesser amount of gameplay, and for some players this seemed like a move to the territory of “walking simulators”. If we knew the importance of planning ability, we would take some action to solve this problem.

The “normal” game, which uses the standard main gameplay loop, does not have such problems. The possibility of planning is built into the image of the implementation of the classic gameplay. Of course, this knowledge can be used to make such games better, but this is by no means necessary. I think it is for this reason that planning as a fundamental aspect of games is so undervalued. The only good example I managed to find [1] is this article by Doug Church, where he explains everything as follows:

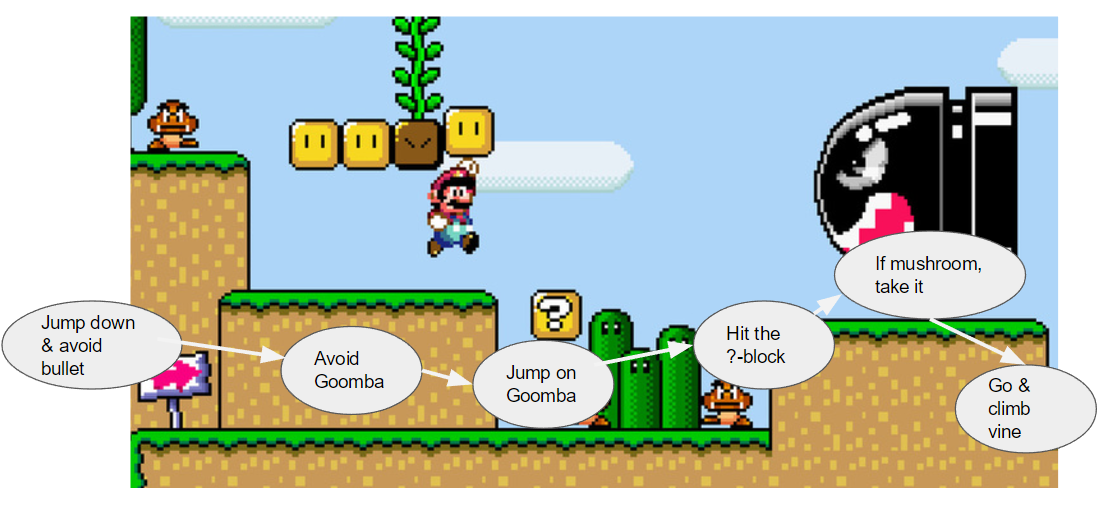

“This simple, logical control combined with highly predictable physics (clear for the world of Mario) allows players to make correct assumptions about what will happen when they act. The complexity of monsters and environments increases, but new and special elements are introduced gradually, and are usually built on the already existing principle of interaction. This makes the game situations clearly defined - it's very easy for players to plan actions. If the players see a high ledge that gets in the way of a monster or a chest under water, they begin to think about what to do with them.

This allows players to participate in a fairly sophisticated planning process. They are introduced (usually indirectly) to how the world works, how they can move and interact with the world, and what obstacles they must overcome. Then, often subconsciously, they change the plan to get where they want. During the game, players create thousands of such small plans, some of which work, and some do not. The important thing is that when the plan fails, the players understand why this happened. The world is so integral that it immediately becomes obvious why the plan did not work. ”

This is a real hit point, an excellent description of what I said. An article from 1999, and it was difficult for me to find other sources discussing it, not to mention the development of this thought from that time. Of course, it can be said that planning is described in Sid Meier’s phrase “A sequence of interesting choices,” but to me it seems too vague. It is not entirely about the aspect of predicting the mechanics of the world and creating plans based on this knowledge.

The only case that roughly fits this principle is the discussion of the Immersive Sim genre. Perhaps this is not very surprising, Doug Church played a big role in the development of this genre. For example, unforeseen gameplay, which is especially famous for immersion simulators, is strongly associated with the ability to understand the world and plan actions based on this information. This type of design ideal is clearly visible in such modern games as Dishonored 2 [2]. Therefore, it is pretty obvious that game designers think in this coordinate system. But it’s much less obvious to me why this is not considered as a fundamental part of what makes games exciting, but as a kind of design subset.

As I mentioned above, this is probably the case because with the participation in the “ordinary” gameplay a large amount of planning occurs automatically. However, this does not apply to the case of narrative games. In fact, narrative games are often considered “not quite games” in the sense that they do not contain much of the usual gameplay compared to games such as Super Mario. For this reason, it is often discussed whether there should be more history or gameplay in games, as if they are necessarily mutually exclusive. However, I believe that the reason for the preservation of such a big discrepancy is that we do not quite correctly understand how the gameplay works in narrative games. As I said in previous posts , in terms of design, we are stuck in local maxima.

The idea that planning is the fundamental basis of games gives us a solution to this problem. Let's not say: “narrative games need better gameplay,” say: “narrative games need better planning.”

To fully understand what we need to do with planning, we need some kind of basic theory to make all this sense. The SSM framework I recently introduced is well suited for this role.

To understand the details, it is better to read a recent post , but for completeness, I will briefly describe the framework here.

We can divide the game into three separate spaces. First, on the system space. All code belongs to it and all modeling is executed in it. The system space works with all components as with abstract symbols and algorithms. Secondly, we have a history space providing the context for events taking place in the system space. In a system space, Mario’s character is simply a collection of collision boundaries, but when this abstract information is passed through the history space, it becomes an Italian plumber. And finally, we have the space of the mental model. It represents how the player thinks about the game and is something like a mental impression of everything that exists in the game world. However, since the player almost never knows exactly what is happening in the system space (and how to interpret the context of the story), this is simply a reasonable assumption. In the end, the mental model is what the player uses to play the game and on what he bases his decisions.

Given all this, we can begin to create a definition of what gameplay is. First, we need to discuss the concept of action. In essence, an action is all that a player does during a game, and it consists of the following steps:

- Evaluation of information obtained from the system and history spaces.

- Creating a mental model based on available information.

- Modeling the consequences of performing a certain action.

- , (, ).

Much of this happens subconsciously. From the player’s point of view, he sees this sequence basically as “doing something” and is not aware of the mental process taking place. But in fact, it always happens when a player does something in the game, whether it be a jump across the chasm in Super Mario or building a house in Sim City.

Having dealt with the fact that such an action, we can proceed to the gameplay. This is a combination of many actions, but with one exception: we do not send the input data to the game, but simply imagine that we are doing this. Therefore, the chain of actions in the space of the mental model is connected together, evaluated, and only then the player begins to send the necessary input data if the results look satisfactory.

In other words: the gameplay is entirely in the planning and subsequent implementation of the plan. And based on all the evidence presented above, my hypothesis is this: the more actions you can combine together, the better the gameplay seems.

It is not enough just to put together any actions and call it a plan. First, the player needs an idea of some goal he is trying to achieve. In addition, actions must be non-trivial. Simply combining a set of walking action will not be exciting for the player. It is also worth pointing out that planning is by no means the only aspect affecting involvement in the game. You cannot cover all other design elements simply because the player is focused on planning.

However, there are many design principles that go hand in hand with planning. For example, it is critical to have a holistic world, because otherwise the player will not be able to plan. That is why invisible walls are so annoying: they make it very difficult to create and execute plans. This also explains why players are annoyed by seemingly random failure. In order for the gameplay to feel good, we need to be able to mentally simulate where the error occurred. As Doug Church said in the quote above: if a player loses, he needs to know why.

Another example is the advice for authors of adventure games: there should always be several puzzles at the same time. From the point of view of planning, this is necessary because you need to give the player space for planning: “First, I will solve this riddle, and then this one.” There are many other principles involved in planning. And although planning is not the only aspect that makes the game exciting, you can extract many useful elements from it.

Let's take a quick look at real examples from real games.

Suppose in this situation, the player wants to kill the enemy in red. Player notwill just jump off and hope for the best. Before you begin, he needs to come up with some kind of plan. He can first wait for the guard to leave, teleport behind the victim, sneak up and stab him. After that, he will leave the place in the same way. This is what a player thinks about before performing any actions. He does not take action until he comes up with a plan.

This plan may not work, for example, the player will not be able to sneak up on the enemy and he will raise the alarm. Failure of the plan does not mean that it was completely wrong. It simply means that he failed to perform one of the actions. If you show it correctly, the player will not be disappointed. In addition, the player may misinterpret his mental model or miss something. This also suits him if he has the ability to change the mental model accordingly. And the next time the player tries to implement a similar plan, he will cope with it more successfully.

Often this ability to fulfill our plans is the most exciting in the game. Usually the game is a little slow at first, because the mental model has not yet been created, and the planning ability is not well developed. But in the course of the game, it becomes better, the player begins to join together longer sequences of actions and therefore gets more pleasure. This is why teaching levels can be so important. This is a great way to get rid of the initial slowness. Learning simplifies gameplay and allows the player to reason correctly about how the game works.

It is also worth noting that plans should never be too easy to execute, otherwise actions become trivial. To keep the game involved, there must always be a certain degree of non-triviality.

Planning does not always have to be long-term, it can be very brief. Take as an example this scene from Super Mario:

Here, the player needs to make a plan in a split second. It is important to note that the player does not just blindly react. Even in a tense situation, if the game works as it should, the player quickly formulates a plan, and then tries to implement it.

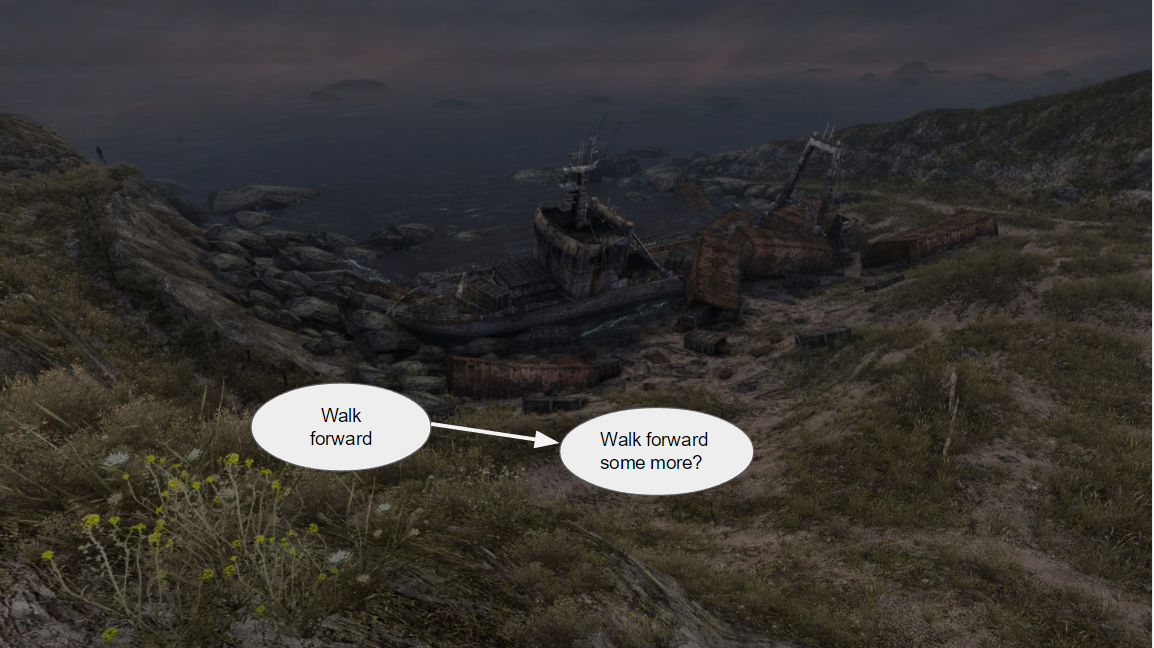

Now let's compare these two examples with a game like Dear Esther:

In this game, you can like a lot, but I think everyone will agree that the gameplay is not enough there. More difficult to agree on what is missing there. I heard a lot about the impossibility of losing and the absence of a competitive mechanic, but I do not think this is convincing. As you may have guessed, I believe that there is no planning.

The main reason why Dear Esther is considered unattractive is not because you cannot lose or have no one to fight with. The game simply does not allow players to create and execute plans. We need to find a way to solve this problem.

Approaching planning within the framework of the SSM framework , we can understand what type of gameplay can be contained in the “narrative game”: when creating a plan in the space of a mental model, it is important that the actions are mostly based on data obtained from the history space.

Compare the following two plans:

1) “First I will collect 10 items to increase the show of character X’s credibility,

which will allow me to achieve the required “friendship” indicator, after which X will become part of my team. This will give me a 10 point ranged bonus. ”

2) “If I help X with cleaning the room, then we can become friends with her. It will be great, because then I can call her on a journey with us. She seems to be a good shot, and with her I will feel much calmer. ”

This is a rather primitive example, but I hope my thought is clear. Both of these approaches describe the same plan, but they are very different in terms of data interpretation. Number 1 occurs in the abstract space of the system, and in number 2 it feels more narrative and based on the space of history. When the gameplay is to create plans that are similar to the second, then something begins to arise in us that is perceived as a truly narrative gameplay. This is a crucial step in the development of interactive storytelling art.

I think that thinking about planning is an essential step towards creating deeper narrative games. For too long, game design has relied on the planning component, which arises naturally from the “standard gameplay,” but now that we don’t have it, we need to pay special attention to it. You need to understand what controls the gameplay, and make sure that these elements are present in the narrative gameplay. Planning is by no means a “silver bullet”, but it’s a really important ingredient. And when developing future Frictional Games, we will definitely think a lot about it.

Notes:

1) If someone has other solid sources that describe planning as a fundamental part of games, I would love to hear about them.

2) Steve Lee gave an excellent lecture on Approach to Holistic Level Design this year at GDC , where we talked a lot about the intentional actions of the player. This is another concept closely related to planning.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/330810/

All Articles