How to adopt a law or data processing in distributed systems in an understandable language

If your work is not related to computer technology, you probably did not think long about how data is stored on computers or in the cloud. I'm not talking about the physical mechanisms of hard drives or memory chips, but about something at the same time more complex and more understandable than you think.

If you have a piece of data that many people want to read and edit at once, for example, a common text file, a bank account or a world in a multiplayer game, how to reach general agreement with what is in the document and make sure that no one overwrites someone else’s work? This is a problem of consensus in distributed systems , and in order to deal with this, I will have to tell you about the sheep, dictators and fictional islands of ancient Greece.

')

“What other islands?”, You ask?

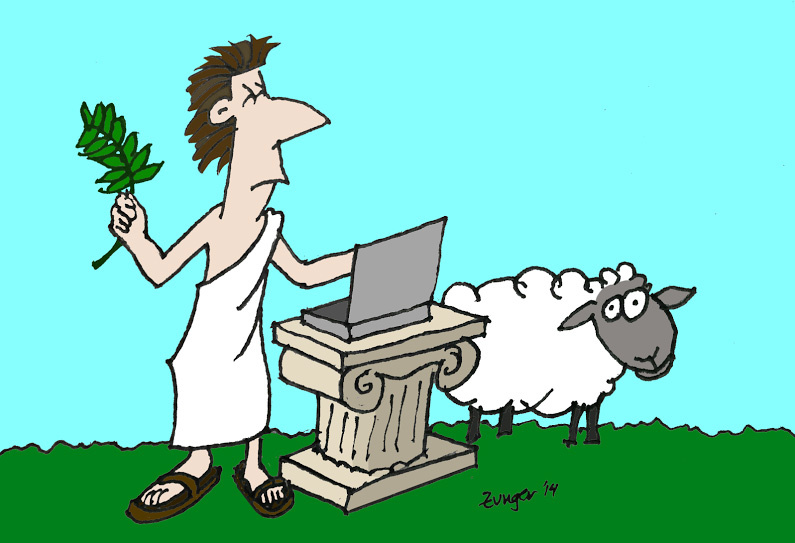

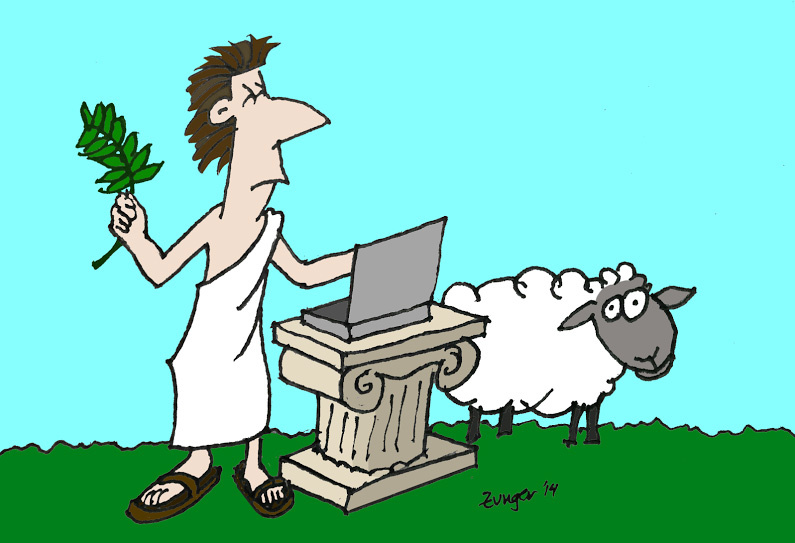

It turns out that the original scientific article about one of the most important methods used to solve this problem was written in the form of a lengthy discussion of how the incomplete composition of the fictional parliament of the ancient Greek island Paxos managed to pass laws, despite the fact that from parliamentarians it was impossible to reliably say when it will appear in parliament. This is an excellent metaphor about how a group of people can agree on what to write to a file, provided that part of the group can be unavailable for some indefinite time. The original article is one of the funniest serious scientific articles ever published and one of the best explanations of the complex algorithm I have ever seen. Since this metaphor worked perfectly in explaining part of the problem of consensus in distributed systems, and since it is much more interesting than talking about file systems, I'm going to use it in this article.

The reason why this metaphor works so well is that in both cases we have some data with files and laws that many people want to change, many people want to read, but no one wants to spend everything on this process. your time Simultaneous reading of a book with a code of laws is limited by the number of people who can see a book at a time, just as reading a file can be limited by the speed at which data can be obtained from the disk. Simultaneous recording requires everyone to agree not to rewrite each other’s decision, but without a lengthy debate to make it. Besides the fact that each person in the world will use the book in turn, how can we solve this problem?

Instead of talking about file systems and database operations, let's move to the islands of the unreal Aegean Sea, where coincidences with reality are random, and residents are obsessed with issuing decrees and laws. We just need to make sure that everyone can read the law whenever they need it. There is a way through several winding stories, and by the time we finish, you will be aware of the problem of distributed consensus, in the form in which IT professionals are confronted. Except for the sheep.

By the way, there will be many islands, and their names are completely invented, besides that, which was the cause of this story, but more on that later.

We begin our story with the simplest case on Pseudemoxos. Here lives one hermit who writes laws and decrees for his own use. At first he used a very simple and understandable method: a notebook and a pencil. He could add laws, change laws and reorganize laws at will, simply erasing and writing down new ones, no matter where he wished (in fact, this is how the disks on our computers worked until the end of the 90s).

This method seemed to work quite well, except for wearing out too much paper. However, the hermit was aware of the terrible lack of such a solution, when once a box of dubious burritos was thrown onto the shore. Making changes in the law - erasing the text and starting to write something, the hermit experienced what we would politely call an “emergency at work”. When the somewhat battered hermit returned to his code, he found that he not only forgot what he was going to write, but now the empty space in the middle of the book is not filled with either old or new law, and scribbles written in haste cannot be read!

A metaphor describes what happens to a computer or program in the event of a failure — the data on the disk can be hopelessly distorted. More serious failures of the hermit can be compared with such events as damage to the block of magnetic heads, which can damage not only the written words, but also leave a rather unpleasant and constant mark on the whole page.

These problems are resolved with journaling. The scheme is not to erase anything, just as people keep logs or laboratory diaries of observations. Now our hermit is holding a pile of papers, and when he wants to make changes to the laws, he adds a new entry to his journal:

June 4, 10:32 - Add to food safety laws: the consumption of burritos that have been at sea for an indefinite period of time is prohibited.

Each edit, be it inserted, modified or deleted, is recorded at the end of the journal with a pen. The hermit is protected from an emergency, because it never erases the record. In the worst case, there is an incomplete, corrupted log entry or traces of a failed write attempt that can be simply ignored. The log has the added advantage of recording all changes. To see how the law looked a year ago, our hermit can simply read the magazine and stop at this date.

One obvious drawback of the magazine is that it is more difficult to read than a notebook. To find out about the current version of the law on food safety, you need to start from the very beginning of the magazine and read to the end, tracking all the changes. As the journal volume increases over time, the process becomes more and more burdensome.

In order to simplify everything, our hermit keeps a pile of empty reference books. Whenever a journal becomes too voluminous, it allocates time to make a lawbook: it reads the journal from beginning to end, formulating the entire law in an up-to-date state, and then writes this state into a collection of laws. On the cover of a code of laws, he writes: “This is a state of law on [such a date].” Further use of the law only requires that he read the law book and the change journal made after the date of the collection of the law. Journals older than this date can be saved if a change history is sometimes required up to a set, or simply thrown away.

If our hermit is too busy developing new legislation and cannot regularly make a set of laws, you can call the clerk (that is, the second computer program working in parallel with the first) to help him. The scribe will read the journal until a certain agreed time, write a set of laws and inform the hermit that he has finished so that he can start using the new collection. There is no need to tell the scribe to do his work, so the hermit can continue his labors in silence.

This method has even more advantages. Our hermit has become widely known for his wisdom (for example, his lessons about the rejection of Mexican cooking, delivered by sea), many people may want to read his laws. As long as these readers are satisfied with a set of laws from a specific date, they can make their own copies and read them freely without having to disturb the sage. Only a person who needs the most recent version of laws should contact him directly.

(The use of journals in personal computers began in the late 1990s and became widespread in the mid-2000s. Your computer probably uses journaling now.)

Near the island of Psevdomoksos is a larger island Fotas (Fotas). This island is sparsely populated, but people are enough for all residents to agree that they need a consolidated system of laws to control their lives. Nonetheless, the residents of the city are known for their irreconcilable independence: they do not allow any other resident or group to rule over them, and therefore they decided that any resident of Fotas will have the power to enact the law. To do this, you just need to write down the law on a sheet of paper with the date, time and your name and send the messenger with him to the Library of Fotas, where the clerk will add it to legal journals.

(This means that many people try to save changes to a single file at the same time without first trying to reach consensus on what will be in the file.)

To see some cases where something might go wrong, let's start a story with Agnes, who lives on one of the coasts of the island and is very concerned about the purity of ritual sacrifices. She introduces the law:

June 1, noon - Law 32.1.2 on the sale of sheep changes as follows: Under the fear of death, it is forbidden to sell or acquire sheep whose wool is not completely white. Signed, Agnia.

On the other side of the island, Bazil, who has several black sheep with whom he has difficulty selling, writes his law:

June 1, noon - Act 32.1.2 of the sale of sheep changes as follows: No one can refuse to buy or sell sheep because of the color of the wool. Signed, Bazil.

A little later, the clerk discovers two new laws with the same time mark. What should he do? When Bazil comes to town to sell the black sheep of Galatea, and she refuses to buy non-white sheep, they will go to read a set of laws. Which version of the law should they use? And what will happen when the clerk tries to collect the next set of laws? (If two people tried to simultaneously write different data to the same part of the same file, the result can be absolutely anything.)

To illustrate a more delicate problem, imagine that Agniya wants to perform the “read-modify-write” operations of the law - she looks at the current law, decides to make changes, and then writes it down. But while she does this, Bazil contributes to the law. For example, at 10:00 am Agniya reads the law

Section 32.1.3. Anyone selling a goat must pay a tax equal to one coin to the general library fund.

She reflects and at 10:02 she writes the following message:

June 1, 10:02 - In Law 32.1.3, it is necessary to change "equal to one coin" to "equal to two coins". Signed, Agnia.

Unfortunately, at 10:01, Bazil, who cannot tolerate goat taxes, writes:

June 1, 10:01 - Law 32.1.3 is replaced by "Mid February - the national olive day." That's it. Signed, Bazil.

Our scribe, trying to reconcile the laws and put them in order, will be very confused: when he comes to the message from Agnes, the law 32.1.3 already establishes the National Olive Day and is never mentioned “equal to one coin”. What should he do? Imagine that Bazil will replace “pay into the general library fund” with “pay for Basil!”.

Similar situations occur when several authors compete in editing the same set of laws. There are many solutions, each of which has its pros and cons. These solutions can be divided into two main types of models. One type is “consistency in the final analysis” or “weak consistency” (eventual consistency), where several rules governing the recording allow everyone to record simultaneously without talking to each other. This model ensures that in the absence of new updates for some time, all copies of the data (replicas) will become consistent. The cost of this approach is that no one can know the exact state of the law at the moment, everyone can only know what it was just recently. The other model is “strict consistency”, in which all types of records are possible, and everyone can know the current state of the law, but with the cost of reaching a consensus for each record.

Both types of models are helpful. Sometimes you have information for which the rate is a bit outdated. For example, when residents of Fotas make their annual photo album. They exchange photos with each other and there is no need to have the most recent photos, so the simpler “consistency in the end” will be good. On the other hand, for these laws, “strict consistency” will be more useful, despite its costs. (This is also true for computers. For example, images that you upload to Google are stored in the system with “consistency in the final analysis”, while access control lists that define viewing rights are stored using strict agreement)

Return to the island Fotas.

We could easily solve the first of our problems — conflicting laws with the same timestamp, simply by adding a rule for a tiebreak so that no labels could be the same. For example, we could add the author's name to the label in alphabetical order, so in the case of a race, changes from Agnia will always be made to Basil. (Or, if the names match, we can assign a unique number to each resident). After the timestamps no longer match, there is no confusion. Galatea comes to the city, and the law of Basil is unique.

If such mutual rewriting is a problem, it can be avoided by first agreeing on who can write something. For example, during one week Agniya can only edit even laws, and Basil is odd, and vice versa next week. (In computers, the file space is often divided in such a way that two authors never try to write the same file at all, and even more so at the same time. For example, each newly uploaded photo can be automatically assigned a unique name.)

To solve the second problem, we eliminate the possibility of its existence: we change the journaling rules in order to prohibit amendments, allowing only a complete replacement, addition or deletion. This means that no wording in the journal can depend on the current state of the law for its interpretation. Agnia would have to write her law in the form

June 1, 10:02 - Law 32.1.3 is replaced by "Any person selling a goat must pay a tax equal to two coins to the Senate." Agnia.

Since her record had a later timestamp, her version of the law easily defeats the version of Basil.

This system of writing laws has the advantages of speed and simplicity: everyone can write the law at any time, without consulting anyone else. However, the use of laws becomes surprisingly difficult. If you want to know the current tax rate for the sale of goats, you go to the library and ask to read Law 32.1.3. Arriving at 10:05, you will read the lawbook and change log. The law says: "Anyone selling a goat must pay a tax equal to one coin to the Senate."

You see, Agniya changed the law at 10:02, but her messenger has not arrived yet! To make the situation a little easier, messengers can register in the library: whenever a messenger arrives from each resident, after delivering the message, they write a note on the blackboard indicating that all the photos of the photo were delivered at such and such a time. Then the visitor can, looking at the board, see that the last message from Agnia was at 9 am, and from Basil at 7 o'clock the night before. Now you, at least, know that the laws you are reading are accurate from 7 o'clock the previous evening - the earliest time shown on the board, and all changes written before that time should have already arrived. (This time is called the “low-water mark”)

Of course, if a particular citizen is not very conflicted, updates from him may be rare, and everyone will wonder: “Has the change just not reached the library yet or is it not?” To avoid this problem, every photo member must send a messenger to the library regularly and regardless of whether they have any updates or not, so that the board remains up to date.

The residents of Fotos are creative people, so they quickly realized that this constant flow of messengers could simplify their lives otherwise. Instead of doing tedious trips to the library, they can simply keep their own copy of the law and the change log. Now their messenger returns every time with all the latest changes in the journal, as well as with a copy of the dates that were on the board. They update their copies and can refer to them.

, , , , . , , . , , : , !

-. , -, . « »: , . , , , , , . , !

. , , , . , , .

( , - . , , , )

, .

-, . , , -, , . , , . ( « »)

-, --. , , . , - , , , .

-, : , , , . , , , , . , . , , , . , , «low-water mark», , !

. , ( , , ) , , . , , , . . , , , , — . , . , , : , , , . , , , .

, , , , Fotans, -. , ? — 10:00, , 9:00 11:00. .

, . , , , , . , . . : , , , . , . , .

, , (LaaS). - , , .

: , . , . (, , , ). . , . , .

, , . , ( ) . 100 . , , - . , !

. --, , , . — , . , , . , 11:58 . .

. , . , , . , . , .

, (Paxos). , . , , , « Paxos». ( )

, , , , . «The Part-Time Parliament» . , , . . , !

, . --, . , , , .

: , , , - . , : , , , - . , , . , , , .

Paxos : , , , . - , , , , , : «! - !» , , . , - , , . , , , , .

: , , ; --, , , . « », « , , , , , , ».

, . , , . , . , . , .

Paxos : «Read-latest», , «read-recent», . «read-recent» Paxos, . . (, , , , , , , ).

, Paxos - , .

, . , , , . , .

, , , . ( , , , ). Paxos , . . , , , . , , , , , , , , .

, . , , , , . , , . - , , , . , , , .

, - , , . - , , . , . - , , .

. , . : « ?» , — , . , , : « ». , . , , .

, , , — , . , , Paxos . Paxos , , ( ).

. ( , ), . , , , , - .

, . — . , . , , , . , , . , . , , . , . « » « ». , , .

— . , , 7:1. !

, , . - , , . . . , , Paxos ( ) . , , , .

. , . , , - , Paxos. , , , , . , , . , , -, , , .

Chubby, .

, Yonatan Zunger, Distinguished Engineer on Privacy at Google

, . : , , , , , ?

, :

* ( ), , . , , , .

* ( ), ( ) , , . , , , , . , , , ( ), .

* ( , , «Paxos»). . , , .

* ( ) — , , - - . , , , .

The best thing about these systems is that, from the client’s point of view, they differ not in the methods, but in the guarantees they provide. Now I will leave you. We wandered through a chain of funny stories about fictional islands, but what you learned is not a childish version of computer science. This is the reality that IT professionals face every day. Therefore, I hope that even if you yourself are not an IT specialist and do not plan to become one, you now have a better understanding of how computer computing is organized in our time.

If you have a piece of data that many people want to read and edit at once, for example, a common text file, a bank account or a world in a multiplayer game, how to reach general agreement with what is in the document and make sure that no one overwrites someone else’s work? This is a problem of consensus in distributed systems , and in order to deal with this, I will have to tell you about the sheep, dictators and fictional islands of ancient Greece.

')

“What other islands?”, You ask?

It turns out that the original scientific article about one of the most important methods used to solve this problem was written in the form of a lengthy discussion of how the incomplete composition of the fictional parliament of the ancient Greek island Paxos managed to pass laws, despite the fact that from parliamentarians it was impossible to reliably say when it will appear in parliament. This is an excellent metaphor about how a group of people can agree on what to write to a file, provided that part of the group can be unavailable for some indefinite time. The original article is one of the funniest serious scientific articles ever published and one of the best explanations of the complex algorithm I have ever seen. Since this metaphor worked perfectly in explaining part of the problem of consensus in distributed systems, and since it is much more interesting than talking about file systems, I'm going to use it in this article.

The reason why this metaphor works so well is that in both cases we have some data with files and laws that many people want to change, many people want to read, but no one wants to spend everything on this process. your time Simultaneous reading of a book with a code of laws is limited by the number of people who can see a book at a time, just as reading a file can be limited by the speed at which data can be obtained from the disk. Simultaneous recording requires everyone to agree not to rewrite each other’s decision, but without a lengthy debate to make it. Besides the fact that each person in the world will use the book in turn, how can we solve this problem?

Instead of talking about file systems and database operations, let's move to the islands of the unreal Aegean Sea, where coincidences with reality are random, and residents are obsessed with issuing decrees and laws. We just need to make sure that everyone can read the law whenever they need it. There is a way through several winding stories, and by the time we finish, you will be aware of the problem of distributed consensus, in the form in which IT professionals are confronted. Except for the sheep.

By the way, there will be many islands, and their names are completely invented, besides that, which was the cause of this story, but more on that later.

Hermits and Mexican Food

We begin our story with the simplest case on Pseudemoxos. Here lives one hermit who writes laws and decrees for his own use. At first he used a very simple and understandable method: a notebook and a pencil. He could add laws, change laws and reorganize laws at will, simply erasing and writing down new ones, no matter where he wished (in fact, this is how the disks on our computers worked until the end of the 90s).

This method seemed to work quite well, except for wearing out too much paper. However, the hermit was aware of the terrible lack of such a solution, when once a box of dubious burritos was thrown onto the shore. Making changes in the law - erasing the text and starting to write something, the hermit experienced what we would politely call an “emergency at work”. When the somewhat battered hermit returned to his code, he found that he not only forgot what he was going to write, but now the empty space in the middle of the book is not filled with either old or new law, and scribbles written in haste cannot be read!

A metaphor describes what happens to a computer or program in the event of a failure — the data on the disk can be hopelessly distorted. More serious failures of the hermit can be compared with such events as damage to the block of magnetic heads, which can damage not only the written words, but also leave a rather unpleasant and constant mark on the whole page.

These problems are resolved with journaling. The scheme is not to erase anything, just as people keep logs or laboratory diaries of observations. Now our hermit is holding a pile of papers, and when he wants to make changes to the laws, he adds a new entry to his journal:

June 4, 10:32 - Add to food safety laws: the consumption of burritos that have been at sea for an indefinite period of time is prohibited.

Each edit, be it inserted, modified or deleted, is recorded at the end of the journal with a pen. The hermit is protected from an emergency, because it never erases the record. In the worst case, there is an incomplete, corrupted log entry or traces of a failed write attempt that can be simply ignored. The log has the added advantage of recording all changes. To see how the law looked a year ago, our hermit can simply read the magazine and stop at this date.

One obvious drawback of the magazine is that it is more difficult to read than a notebook. To find out about the current version of the law on food safety, you need to start from the very beginning of the magazine and read to the end, tracking all the changes. As the journal volume increases over time, the process becomes more and more burdensome.

In order to simplify everything, our hermit keeps a pile of empty reference books. Whenever a journal becomes too voluminous, it allocates time to make a lawbook: it reads the journal from beginning to end, formulating the entire law in an up-to-date state, and then writes this state into a collection of laws. On the cover of a code of laws, he writes: “This is a state of law on [such a date].” Further use of the law only requires that he read the law book and the change journal made after the date of the collection of the law. Journals older than this date can be saved if a change history is sometimes required up to a set, or simply thrown away.

If our hermit is too busy developing new legislation and cannot regularly make a set of laws, you can call the clerk (that is, the second computer program working in parallel with the first) to help him. The scribe will read the journal until a certain agreed time, write a set of laws and inform the hermit that he has finished so that he can start using the new collection. There is no need to tell the scribe to do his work, so the hermit can continue his labors in silence.

This method has even more advantages. Our hermit has become widely known for his wisdom (for example, his lessons about the rejection of Mexican cooking, delivered by sea), many people may want to read his laws. As long as these readers are satisfied with a set of laws from a specific date, they can make their own copies and read them freely without having to disturb the sage. Only a person who needs the most recent version of laws should contact him directly.

(The use of journals in personal computers began in the late 1990s and became widespread in the mid-2000s. Your computer probably uses journaling now.)

Chaos on Fotas

Near the island of Psevdomoksos is a larger island Fotas (Fotas). This island is sparsely populated, but people are enough for all residents to agree that they need a consolidated system of laws to control their lives. Nonetheless, the residents of the city are known for their irreconcilable independence: they do not allow any other resident or group to rule over them, and therefore they decided that any resident of Fotas will have the power to enact the law. To do this, you just need to write down the law on a sheet of paper with the date, time and your name and send the messenger with him to the Library of Fotas, where the clerk will add it to legal journals.

(This means that many people try to save changes to a single file at the same time without first trying to reach consensus on what will be in the file.)

To see some cases where something might go wrong, let's start a story with Agnes, who lives on one of the coasts of the island and is very concerned about the purity of ritual sacrifices. She introduces the law:

June 1, noon - Law 32.1.2 on the sale of sheep changes as follows: Under the fear of death, it is forbidden to sell or acquire sheep whose wool is not completely white. Signed, Agnia.

On the other side of the island, Bazil, who has several black sheep with whom he has difficulty selling, writes his law:

June 1, noon - Act 32.1.2 of the sale of sheep changes as follows: No one can refuse to buy or sell sheep because of the color of the wool. Signed, Bazil.

A little later, the clerk discovers two new laws with the same time mark. What should he do? When Bazil comes to town to sell the black sheep of Galatea, and she refuses to buy non-white sheep, they will go to read a set of laws. Which version of the law should they use? And what will happen when the clerk tries to collect the next set of laws? (If two people tried to simultaneously write different data to the same part of the same file, the result can be absolutely anything.)

To illustrate a more delicate problem, imagine that Agniya wants to perform the “read-modify-write” operations of the law - she looks at the current law, decides to make changes, and then writes it down. But while she does this, Bazil contributes to the law. For example, at 10:00 am Agniya reads the law

Section 32.1.3. Anyone selling a goat must pay a tax equal to one coin to the general library fund.

She reflects and at 10:02 she writes the following message:

June 1, 10:02 - In Law 32.1.3, it is necessary to change "equal to one coin" to "equal to two coins". Signed, Agnia.

Unfortunately, at 10:01, Bazil, who cannot tolerate goat taxes, writes:

June 1, 10:01 - Law 32.1.3 is replaced by "Mid February - the national olive day." That's it. Signed, Bazil.

Our scribe, trying to reconcile the laws and put them in order, will be very confused: when he comes to the message from Agnes, the law 32.1.3 already establishes the National Olive Day and is never mentioned “equal to one coin”. What should he do? Imagine that Bazil will replace “pay into the general library fund” with “pay for Basil!”.

Similar situations occur when several authors compete in editing the same set of laws. There are many solutions, each of which has its pros and cons. These solutions can be divided into two main types of models. One type is “consistency in the final analysis” or “weak consistency” (eventual consistency), where several rules governing the recording allow everyone to record simultaneously without talking to each other. This model ensures that in the absence of new updates for some time, all copies of the data (replicas) will become consistent. The cost of this approach is that no one can know the exact state of the law at the moment, everyone can only know what it was just recently. The other model is “strict consistency”, in which all types of records are possible, and everyone can know the current state of the law, but with the cost of reaching a consensus for each record.

Both types of models are helpful. Sometimes you have information for which the rate is a bit outdated. For example, when residents of Fotas make their annual photo album. They exchange photos with each other and there is no need to have the most recent photos, so the simpler “consistency in the end” will be good. On the other hand, for these laws, “strict consistency” will be more useful, despite its costs. (This is also true for computers. For example, images that you upload to Google are stored in the system with “consistency in the final analysis”, while access control lists that define viewing rights are stored using strict agreement)

Return to the island Fotas.

In the end, everything makes sense

We could easily solve the first of our problems — conflicting laws with the same timestamp, simply by adding a rule for a tiebreak so that no labels could be the same. For example, we could add the author's name to the label in alphabetical order, so in the case of a race, changes from Agnia will always be made to Basil. (Or, if the names match, we can assign a unique number to each resident). After the timestamps no longer match, there is no confusion. Galatea comes to the city, and the law of Basil is unique.

If such mutual rewriting is a problem, it can be avoided by first agreeing on who can write something. For example, during one week Agniya can only edit even laws, and Basil is odd, and vice versa next week. (In computers, the file space is often divided in such a way that two authors never try to write the same file at all, and even more so at the same time. For example, each newly uploaded photo can be automatically assigned a unique name.)

To solve the second problem, we eliminate the possibility of its existence: we change the journaling rules in order to prohibit amendments, allowing only a complete replacement, addition or deletion. This means that no wording in the journal can depend on the current state of the law for its interpretation. Agnia would have to write her law in the form

June 1, 10:02 - Law 32.1.3 is replaced by "Any person selling a goat must pay a tax equal to two coins to the Senate." Agnia.

Since her record had a later timestamp, her version of the law easily defeats the version of Basil.

This system of writing laws has the advantages of speed and simplicity: everyone can write the law at any time, without consulting anyone else. However, the use of laws becomes surprisingly difficult. If you want to know the current tax rate for the sale of goats, you go to the library and ask to read Law 32.1.3. Arriving at 10:05, you will read the lawbook and change log. The law says: "Anyone selling a goat must pay a tax equal to one coin to the Senate."

You see, Agniya changed the law at 10:02, but her messenger has not arrived yet! To make the situation a little easier, messengers can register in the library: whenever a messenger arrives from each resident, after delivering the message, they write a note on the blackboard indicating that all the photos of the photo were delivered at such and such a time. Then the visitor can, looking at the board, see that the last message from Agnia was at 9 am, and from Basil at 7 o'clock the night before. Now you, at least, know that the laws you are reading are accurate from 7 o'clock the previous evening - the earliest time shown on the board, and all changes written before that time should have already arrived. (This time is called the “low-water mark”)

Of course, if a particular citizen is not very conflicted, updates from him may be rare, and everyone will wonder: “Has the change just not reached the library yet or is it not?” To avoid this problem, every photo member must send a messenger to the library regularly and regardless of whether they have any updates or not, so that the board remains up to date.

The residents of Fotos are creative people, so they quickly realized that this constant flow of messengers could simplify their lives otherwise. Instead of doing tedious trips to the library, they can simply keep their own copy of the law and the change log. Now their messenger returns every time with all the latest changes in the journal, as well as with a copy of the dates that were on the board. They update their copies and can refer to them.

, , , , . , , . , , : , !

-. , -, . « »: , . , , , , , . , !

. , , , . , , .

( , - . , , , )

, .

-, . , , -, , . , , . ( « »)

-, --. , , . , - , , , .

-, : , , , . , , , , . , . , , , . , , «low-water mark», , !

. , ( , , ) , , . , , , . . , , , , — . , . , , : , , , . , , , .

, , , , Fotans, -. , ? — 10:00, , 9:00 11:00. .

, . , , , , . , . . : , , , . , . , .

, , (LaaS). - , , .

: , . , . (, , , ). . , . , .

, , . , ( ) . 100 . , , - . , !

. --, , , . — , . , , . , 11:58 . .

. , . , , . , . , .

, (Paxos). , . , , , « Paxos». ( )

, , , , . «The Part-Time Parliament» . , , . . , !

, . --, . , , , .

: , , , - . , : , , , - . , , . , , , .

Paxos : , , , . - , , , , , : «! - !» , , . , - , , . , , , , .

: , , ; --, , , . « », « , , , , , , ».

, . , , . , . , . , .

Paxos : «Read-latest», , «read-recent», . «read-recent» Paxos, . . (, , , , , , , ).

, Paxos - , .

:

, . , , , . , .

, , , . ( , , , ). Paxos , . . , , , . , , , , , , , , .

, . , , , , . , , . - , , , . , , , .

, - , , . - , , . , . - , , .

. , . : « ?» , — , . , , : « ». , . , , .

, , , — , . , , Paxos . Paxos , , ( ).

. ( , ), . , , , , - .

, . — . , . , , , . , , . , . , , . , . « » « ». , , .

— . , , 7:1. !

, , . - , , . . . , , Paxos ( ) . , , , .

. , . , , - , Paxos. , , , , . , , . , , -, , , .

Chubby, .

Eventually

, Yonatan Zunger, Distinguished Engineer on Privacy at Google

, . : , , , , , ?

, :

* ( ), , . , , , .

* ( ), ( ) , , . , , , , . , , , ( ), .

* ( , , «Paxos»). . , , .

* ( ) — , , - - . , , , .

The best thing about these systems is that, from the client’s point of view, they differ not in the methods, but in the guarantees they provide. Now I will leave you. We wandered through a chain of funny stories about fictional islands, but what you learned is not a childish version of computer science. This is the reality that IT professionals face every day. Therefore, I hope that even if you yourself are not an IT specialist and do not plan to become one, you now have a better understanding of how computer computing is organized in our time.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/330462/

All Articles