Designing and developing a template engine in C # and ANTLR

Prehistory

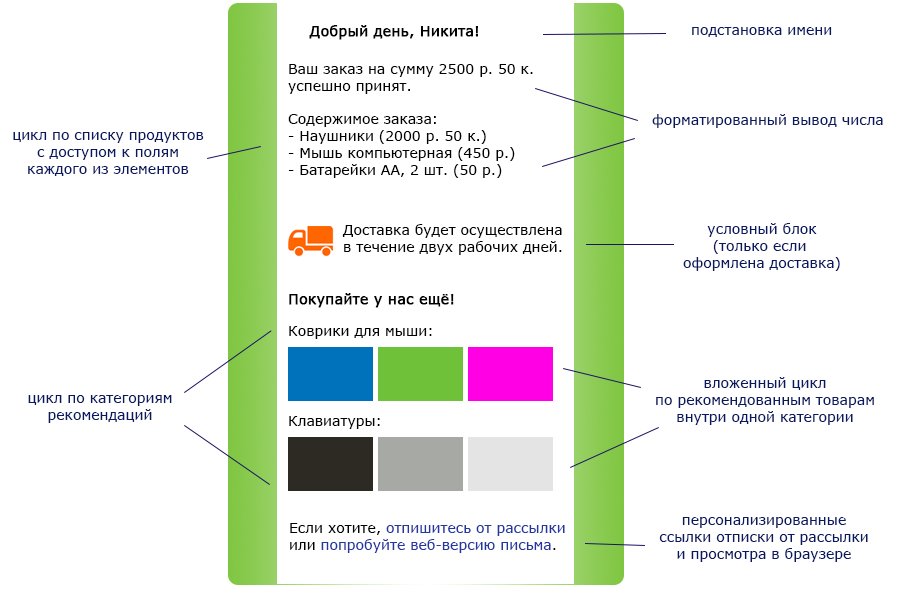

For many years we have been helping our customers send good, informative and human letters to consumers. Instead of the dry “Good day”, we write “Hello, Nikita!” In them, and instead of “Your balance has increased,” we report “you received 25 points”. But marketers are becoming more creative, and a modern letter from an online store should look like this:

And we want to be able to generate such letters automatically.

Our old, time-tested template engine can insert parameters into the right places of the letter, substitute something by default for the missing value and write “1 ruble, 2 rubles, 5 rubles”, and does it well. But it is not intended for complex branches, cycles, and any other complex logic. Therefore, to form complex letters like in the picture, we had to resort to C # code, and it looked like this:

We ended up in a not very pleasant universe, where the client’s desire to italicize a word in a letter leads to a ticker for a programmer and a layout for production. We did not want to linger in this universe, and it became clear that we needed a new template engine, which should be able to:

- simple parameter output

- output of complex multi-level parameters (Recipient.Address.City.Name)

- conditions

- cycles

- arithmetic operations

And these are just business requirements based on real-world scenarios. And since we want to make it easy for the manager to get started when sending newsletters and difficult to make mistakes, we need more:

- clear error messages

- validation of parameters used in the template

- extensibility (ability to add your own functions)

And since we sometimes send millions of emails per hour, we need good performance, which means:

- precompile template

- reuse pattern and thread safety

We looked at several of the available template engines, starting Liquid and ending with Mustache , and all of them are a bit weird. Someone fails with the exception with an error, but simply renders an empty string. Somewhere syntax is such that we, being programmers, could not figure out how to write a condition. We seriously approached the insane idea of using Razor , close and understandable to us, to form letters, but refused it because of the annoying little things: it turned out that the author of the mailing template could execute arbitrary .NET code in the process that sends the letter.

And of course, in the end, we decided to write our own template engine. With static typing and filter chains.

Language design

Almost immediately, we decided to abandon compatibility with something. They rejected backward compatibility with the previous template engine: the syntax should be such that it can organically expand the language five years in the future, and not adapt to what has been developed for five years in the past. They abandoned compatibility with some de facto standard, according to which everyone imposes letter templates: it simply does not exist. We found ourselves in front of a completely white board on which we had to draw the syntax of our language, and immediately began to invent our own framework in which to create.

First, the language must be embedded in HTML, which means it must provide escape sequences that separate our code blocks from the rest of the markup.

We stopped at this option:

The idea of separating the output instructions ${ … } and the non-output, service instructions @{ … } inspired by implicit and explicit expressions from Razor . We tried to see how it would look in a real HTML-layout, and yes, it turned out better and clearer.

Later they remembered that the same syntax is used in TypeScript for string interpolation (and in C # it is different, but also similar ). It was nice: if Anders Hejlsberg considered this a good syntax, then we are on the right track.

Secondly, we thought who would use our template language. Most likely, the layout will be done by a layout designer to whom javascript is close and understandable. On the other hand, the manager who does not know javascript, but knows English and common sense will most likely refine the layout of small things and correct little things in logic. Therefore, our syntax in the end turned out to be more similar to Pascal, with normal human words and , or , not instead of stitches and ampersands.

As a result, we stopped at this syntax:

All that remains is nothing: blow the dust off the “dragon book” and implement lexical parsing, parsing, semantic analysis, and then ensure the generation of the output result - the letter.

Parsing and ANTLR

It should be obvious to everyone that Chomsky’s classification of the language invented by us is described by context-free LL grammar, to parse which, respectively, it suffices to implement LL (*) - the parser. And here we are faced with a small problem: we almost do not understand this and are not able to.

We are well able to do complex web front-end with a large number of javascript, do complex server validation, work with terabyte databases and solve problems of performance and multithreading in terms of thousands of transactions per minute. But linguistic grammars are not entirely our competence. And ideally we have two weeks to develop a template engine.

At this place we went and entered the following cheat code in Google: ANTLR. The effect was not instantaneous, but after a couple of days spent reading the documentation and experiments, we got the kind of progress that would have taken a few weeks with manual development. So what is Antlr and what does it take on?

ANTLR (ANother Tool for Language Recognition) is an open library written by Terrence Parr, a professor at the University of San Francisco and the author of more than a dozen scientific articles on formal grammars and their analysis. Little by little, it is used for parsing by guys from Google, Oracle and Microsoft (for example, in ASP.NET MVC). Antlr fully assumes the lexical and syntactic analysis of the text, guided by the formal description of the grammar of the language.

Of course, not everything was cloudless. On close acquaintance, Antlr turned out to be a java-utility that needs to be run from the command line, trying to find the right arguments from conflicting articles of the documentation, so that it generates a C # code for which StyleCop will swear. The documentation was found, but not everything that is implemented in the utility is described in the documentation, and - this was a blow - not everything that is described in the documentation (the official book from the author of the library) is already implemented in the utility. C # support was not as complete as Java support, and from the working support tools we found only a plug-in to Eclipse .

We can safely close our eyes to all this, because after we made this stupid thing work, we received a code that receives the stream with the text, and returns the complete syntax tree and classes to work around it.

We did not write a template parser and never plan to do this in the future. We described the grammar of the language, entrusting Antlr with the solution to boring everyday problems associated with its parsing, and left to ourselves interesting and unexpected problems related to everything else.

Language Grammar: Lexical Rules

The ANTLR grammar description is made up of a set of recursive rules. Anyone who has met the BNF , Wirth diagrams, or other means of describing formal languages in the first or second year will be close to this idea.

In the same way, we are close to the idea of maximum separation of lexical analysis from syntactic analysis. We gladly took the opportunity to spread the rules defining terminals and primitive tokens of the language in different files, from syntax rules describing more complex composite and high-level constructions.

We took the rules lexer. The most important task is to make sure that we recognize our language only inside ${ ... } and @{ .... } blocks, and leave the rest of the letter text unchanged. In other words, the grammar of our language is island grammar , where the text of the letter is uninteresting “ocean” for us, and the inserts in curly brackets are interesting “islands”. The ocean block is absolutely opaque for us, we want to see it as one large token. In the block of the island we want the most specific and detailed analysis.

Fortunately, Antlr supports island grammars out of the box thanks to the mechanism of lexical modes. Formulating the rules by which we divide the text into the “ocean” and “islands” was not entirely trivial, but we managed:

These rules put the parser into “inside instruction” mode. There are two of them, because earlier we decided to have a slightly different syntax for control instructions and output instructions.

In the “inside instruction” mode, a symmetric rule that returns the parser to the main mode when it encounters a closing brace.

The keywords “popMode” and “pushMode” hint to us that the parser has a mode stack, and they can be nested with some impressive depth, but for our grammar it is enough to switch from one mode to another and then come back.

It remains to describe in the “ocean” a rule that will describe everything else, all text that is not an input to the instructions mode:

This rule will be perceived as Fluff (nonsense, husks, minor garbage) any string of characters that does not contain @ and $ , or exactly one character $ or @ . The Fluff token chain can then and must be glued together into one string constant.

It is important to understand that the lexer tries to apply the rules as eagerly as possible, and if the current character satisfies two rules, the rule that captures the largest number of following characters will always be chosen. That is why, when a sequence of ${ encountered in the text, the lexer will interpret it as an OutputInstructionStart , and not as two Fluff tokens for one character.

So, we learned to find the “islands” of our grammar. This is a sterile and controlled space inside the template, where we decide what is possible and what is not, and what each symbol means. This will require other lexical rules that work inside the instruction mode.

We do not write a Python compiler and want to allow spaces, tabs, and line breaks wherever it looks reasonable. Fortunately, this also allows Antlr:

Such a rule, of course, can only exist in the "island" mode, so that we do not cut spaces and line breaks in the text of the letter.

The rest is simple: we look at the approved example of the syntax and methodically describe all the tokens that we meet in it, starting with DIGIT

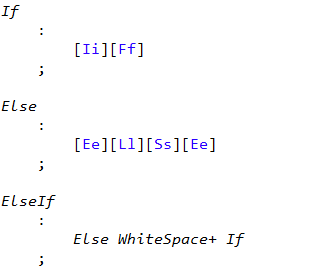

and ending with keywords ( IF , ELSE , AND and others):

Register independence looks scary, but the documentation reasonably says that lexical analysis is an exact thing and implies the most explicit description, and heuristics, by definition, are not in all alphabets in the world. We did not argue with that. But we have else if perceived as one token (which is convenient), but at the same time it is not elsif and not elseif , as it happens in some languages.

From somewhere in the depths of memories of the first and second year, disturbed by the words about the BNF and the Wirth diagram, an understanding emerges of how to describe IDENTIFIER so that the identifier can begin only with a letter:

A few dozen are not the most complex rules, and you can emerge a level above - in the syntax analysis.

Language Grammar: Syntax Rules

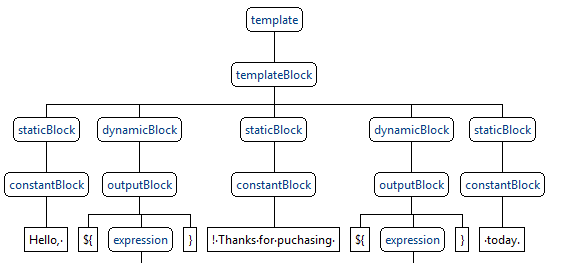

The structure of any letter in our templating system is simple and resembles a zebra: static layout blocks alternate with dynamic ones. Static blocks are layouts with parameter substitution. Dynamic is cycles and branching. We described these basic blocks with the following set of rules (not fully given):

The syntax rules are described in the same way as the lexical rules, but they are not based on specific symbols (terminals), but on lexemes described by us (with a capital letter) or other syntax rules (with a small letter).

Having examined the text with this set of rules, we got something similar:

In static and dynamic blocks, there can be a set of instructions of arbitrary complexity, starting with the derivation of a single parameter and ending with complex branching based on the results of performing arithmetic operations within the loop. In total, we got about 50 syntactic rules of this type:

Here we describe a complex conditional statement in which an if block is required, there may be several else if blocks else if and there may be (but not necessarily) one else block. In the If block inside the familiar to us templateBlock is the one that can be anything, including another condition.

Somewhere in this place, our grammar began to be really recursive, and it became creepy. Putting the last closing brace, we generated the parser code of our grammar using ANTLR, connected it to our project and wondered what to do with all this.

From tree to tree

The result of Antlr from version 4 is a parser that turns the text into a so-called concrete syntax tree , it is also a parser tree. By concrete is meant that the tree contains all the information about the syntax, every service word, every brace and comma. This is a useful tree, but not exactly what is needed for our tasks. Its main problems are too much connectedness with the syntax of the language (which will inevitably change) and perfect ignorance about our subject area. Therefore, we decided to bypass this tree exactly once and build on its basis our own tree, which is closer to the abstract syntax tree and is more convenient for further use.

Requirements for the tree are:

- It should not contain details of the syntax (it is important for us that there is a branch into three branches, and the words

if,else ifandelsenot interesting) - Must support all typical bypass scripts (letter rendering with parameter value substitution, getting a list of parameters and their types)

The simplified interface of the top of our tree ultimately looks like this (the set of descendants and the logic of their traversal are too different for different nodes, therefore they are not in the general interface):

internal interface ITemplateNode { void PerformSemanticAnalysis(AnalysisContext context); void Render(StringBuilder resultBuilder, RenderContext renderContext); } Inspired by the stories of the creators of Roslyn about red-green trees , we decided that our tree would be completely immutable. First, it is easier and easier to work with such code without asking questions about the state and sequence of changes. Secondly, this is the easiest way to provide thread safety, which means that you can use one precompiled letter template to send in many threads. In general, the beauty left to build it.

It is suggested to bypass the parser tree generated by Antlr using the Visitor pattern. Antlr itself provides the visitor interface, as well as a basic implementation, which goes all the vertices of the tree in depth, but does nothing at the same time.

Of course, there is an option to make one giant visitor, which will implement a detour of all our rules, of which there’s not so much, but almost 50. But it’s much more convenient to describe several different visitors, the task of each of which is to construct one vertex of our resultant tree.

For example, to bypass conditions inside @{ if } … {else if } … {else } .. @{ end if } we use a special visitor:

internal class ConditionsVisitor : QuokkaBaseVisitor<ConditionBlock> { public ConditionsVisitor(VisitingContext visitingContext) : base(visitingContext) { } public override ConditionBlock VisitIfCondition(QuokkaParser.IfConditionContext context) { return new ConditionBlock( context.ifInstruction().booleanExpression().Accept( new BooleanExpressionVisitor(visitingContext)), context.templateBlock()?.Accept( new TemplateVisitor(visitingContext))); } public override ConditionBlock VisitElseIfCondition(QuokkaParser.ElseIfConditionContext context) { return new ConditionBlock( context.elseIfInstruction().booleanExpression().Accept( new BooleanExpressionVisitor(visitingContext)), context.templateBlock()?.Accept( new TemplateVisitor(visitingContext))); } public override ConditionBlock VisitElseCondition(QuokkaParser.ElseConditionContext context) { return new ConditionBlock( new TrueExpression(), context.templateBlock()?.Accept( new TemplateVisitor(visitingContext))); } } It encapsulates the logic of creating a ConditionBlock object from a fragment of the syntactic tree describing the branch of the conditional operator. Since inside the condition there can be an arbitrary piece of the template (the grammar is something recursive), the control for parsing everything inside is again transferred to the universal visitor. Our visitors are related recursively about the same way as grammar rules.

In practice, it is easy and convenient to work with such small visitors: they only bypass those elements of the language that we expect to see in each particular place, and their work consists either in instantiating a new vertex of the tree that we are building or in transferring control to another visitor. which deals with a narrower task.

At the same stage, we get rid of some inevitable formal grammar artifacts, such as redundant brackets, conjunctions and single argument clauses, and other things needed to define left-recursive grammar and absolutely unnecessary for applied tasks.

As a result, we obtain from such a tree

such a

This tree is much better placed in the head, does not contain useless information, its nodes encapsulate the implementation of specific instructions, and in general you can work with it.

It remains quite a bit - to bypass it several times. And the first, required traversal is a traversal for semantic analysis.

Getting the list of parameters and typing

One of the key tasks of our template engine is the ability to find in the text of the letter all the parameters used in it. The goal is clear: to validate and not to save the template, in which there are parameters that we can not substitute in the letter. For example, Recipient.Email we know, but Recipietn.Eamil is not. It is important for us that the sender learns about the error in the template immediately when it is saved, and not when trying to send an email.

However, this is not the only direction of parameter validation. Do we want to write ${ Recipient.Email + 5 } in the letter, knowing that Email in our system is a string field? It seems not. It means that we must not only find all the parameters in the letter, but also determine their type. At this point, we thought about typing and realized that it is static (which is good), but implicitly (which is convenient for the user, but inconvenient for us). We felt a fleeting impulse to make the manager declare all the parameters at the beginning of the letter, indicating the type. User friendliness won, momentum suppressed. It is necessary to determine the type “on the fly” based on the context.

The type system of our template engine looks like this:

- primitive type

- integer

- a fractional number

- boolean value

- date Time

- a composite type containing named properties of any type

- a multiple type (array, collection, list, whatever) containing several values of one specific type

The approach to solving the problem is simple: in order to determine the type of the parameter included in the letter, it is enough to find all its uses in the text and try to determine a consistent type that satisfies all occurrences or report a template error. In practice, this was not the easiest task with a bunch of special cases that need to be taken into account.

It turned out that the loop variables have scope. It turned out that there are nested loops on the list of lists. It turned out that you can loop through the same list in two different places in the template, and refer to different fields of the list items. In general, we needed a strong static analysis, which we had to think about as well as a few dozen unit tests, but we are happy with the result.

Looking at this template, we can say that the consumer must have an array of products, and each product has a price and an array of categories, and each category must have both an identifier Id and the name Name . Now it’s enough to ask our system if there are any parameters of such a structure in it, and there will be no surprises when sending it. .

: , , - ( ).

: , , , .

, ? , :

, B = 0. – , , - :

, , , , :

- reasonable defaults ( null- , null- false, NaN )

- fail fast

: , . , . fail fast, , , .

, . , - : - , , . , . , , :

internal class ToUpperTemplateFunction : ScalarTemplateFunction<string, string> { public ToUpperTemplateFunction() : base( "toUpper", new StringFunctionArgument("string")) { } public override string Invoke(string argument1) { return argument1.ToUpper(CultureInfo.CurrentCulture); } } : , - , , .

Results

, . , , , Not invented here – , , , .

, , , , , .

, , - , , .

References:

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/329772/

All Articles