Web Scrolling: Primer

By Nolan Lawson, Microsoft Edge Project Manager

Scrolling is one of the most ancient interactions on the web. Long before the advent of the pull-to-refresh methods and endless download lists, the modest scroll bar solved the initial scaling problem on the web: how to interact with content that extends beyond the available viewing area?

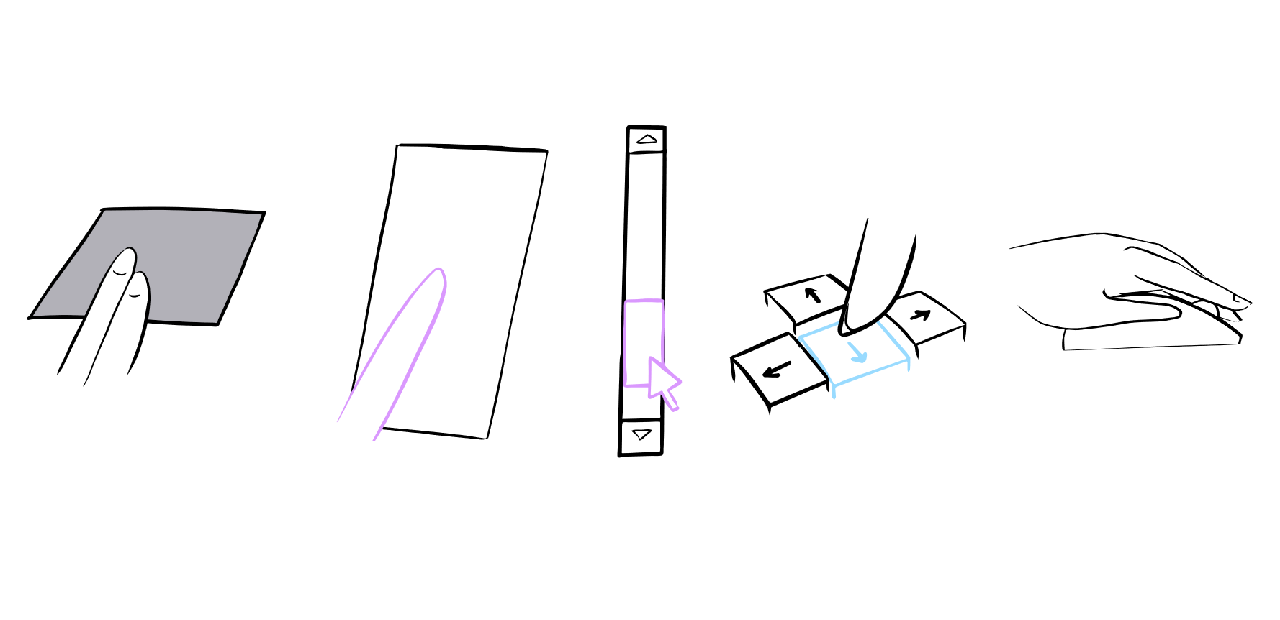

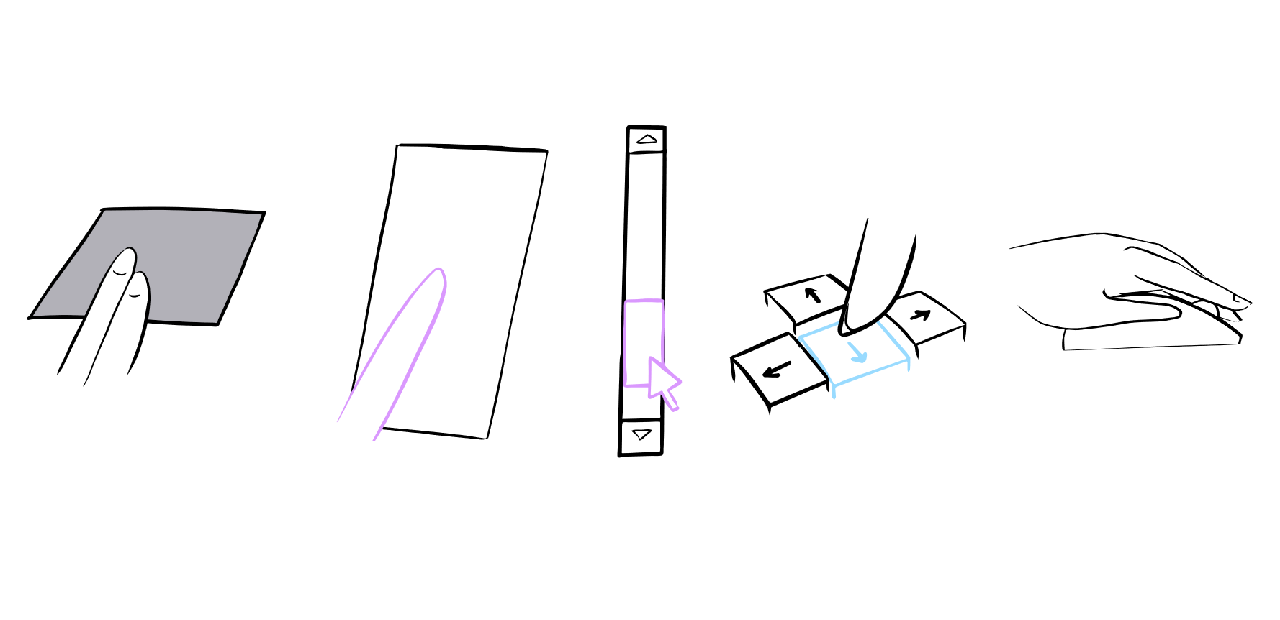

Today, scrolling is still the most fundamental interaction on the Web, and perhaps the most misunderstood. For example, do you know the difference between the following scenarios?

If you ask the average Internet user (or even the average web developer!), They can tell you that these actions are equivalent. The truth is much more interesting.

As it turns out, these five input methods have very different characteristics, especially in terms of performance and cross-browser compatibility. Some of them (like scrolling on the touchscreen) are likely to be smooth even on a page using heavy javascript, while from others (like scrolling from the keyboard) the same page will lag and become insensitive. Moreover, some types of scrolling can be slowed down by DOM event handlers, while others cannot. What's going on here?

')

To answer this question and understand how to implement the smoothest scrolling for your site, let's step back to understand and see how browsers deal with multithreading and input.

Conceptually, the web is a single-threaded environment. JavaScript blocks DOM, and DOM blocks JavaScript, because both are fighting for the same thread, often called the “main thread” or the “UI thread”.

For example, if you add this (horrible) JavaScript snippet to a page, you will immediately notice a deterioration in performance:

While this JavaScript is spinning in an infinite loop, the buttons do not work, the elements of the forms do not react and even the animated GIFs slow down - in all senses and relationships, the page is frozen. You can study the effect in action in a simple demo .

Moreover, if you try to scroll the page with the "up" and "down" keys on the keyboard, the page is predictably stuck until JavaScript stops running. All this is clear evidence of our presentation of the web as a single-threaded environment.

There is a funny anomaly: if you try to scroll through the touchscreen, the page scrolls up and down perfectly, although JavaScript blocks everything else on the page. The same applies to scrolling from the touchpad, mouse wheel and scrolling after the page is captured with the click-and-drag cursor (depending on the browser).

Somehow, some scrolling actions can change the state of the page, while everything else — buttons, data entry fields, GIFs — is completely frozen. How can we combine this with our single-threaded web theory?

As it turns out, in general, the thesis “single-threaded browsers” is true, but there are important exceptions. Scrolling, in all its diversity, is one such exception.

Over the years, browser developers have realized that unloading auxiliary work into background threads can provide significant benefits in terms of smoothness and sensitivity. Scrolling is so important for a key browser experience that this task was quickly chosen for this optimization. Nowadays, all the major browser engines (Blink, EdgeHTML, Gecko, WebKit) support scrolling beyond the main thread of execution to one degree or another (Firefox was the last to join the club, from Firefox version 46 ).

With background scrolling, even a cluttered page will scroll smoothly, because all scrolling is performed in a separate thread. Only if you try to interact with the page through some extraneous mechanism that is not related to scrolling - press a key, enter data in the input field, click on the link - then the facade is reset and the essence of the salon stunt fully reveals itself. (Considering how well it works, this is a great trick!)

True, asynchronous scrolling has a common side effect, which is called the checkerboard effect . It first appeared on the Safari for iOS in the form of gray and white cells, as if from a chessboard. In most modern browsers, the effect appears as empty space on the screen if you scroll faster than the browser can render the page. This is not ideal, but it is an acceptable compromise compared to a locked, jerking or non-replicable scrolling.

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to transfer scrolling to a background thread. Browsers can do this only if the operating system allows simultaneous input, and this may vary from device to device. In particular, keyboard input is not as optimized as mouse or touch device input, which ultimately leads to more significant lags when typing from the keyboard in all browsers.

There will be an instructive little story. When operating systems like Windows and macOS first came out, they allowed only one thread of execution, and very few people foresaw the need to provide for simultaneous input. It was only when multi-core machines appeared that the operating systems began to build parallelism into their architecture.

Just as the rudimentary organs of animals make their evolutionary history understand, the single-threaded origin of operating systems manifests itself when looking at how to scroll on the web. Only if the operating system allows parallel input — from a mouse, keyboard, or other device — can browsers effectively optimize scrolling so that it is not affected by the lengthy execution of JavaScript that has trapped the main thread of execution.

However, in the Microsoft Edge development team, we are making progress to ensure smooth and responsive scrolling, regardless of its method. In EdgeHTML 14 (which is included with Windows 10 Anniversary Update), we support background scrolling for the following methods:

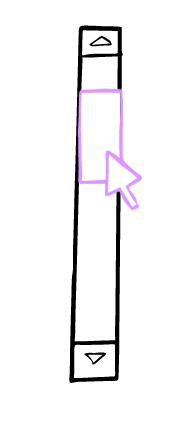

If you compare Edge with other desktop browsers, you'll notice that only it supports asynchronous scrolling using the scroll bar, i.e., holding and moving the scroll slider with the mouse, clicking on the scroll bar or arrows. (Actually, we presented this feature without the announcement back in the Anniversary Update!)

According to the test results in Windows 10 (14393, Surface Book) and macOS Sierra (10.12, MacBook Air), we got the following results:

As this table demonstrates * , scrolling behavior can dramatically change from browser to browser, and even from one OS to another. If you test one method of scrolling in only one browser, you will get very incomplete results of the performance of your site, compared to how users actually work with it!

In general, it should be clear that scrolling has a special place on the web and browsers work very hard to make it fast and responsive. However, there are subtle ways that a web developer can inadvertently disable browser optimizations. Let's look at how web developers can influence the scrolling in the browser, in an amicable and bad way.

Background scrolling gives a tangible increase in efficiency - scrolling and JavaScript are completely separate, allowing them to work in parallel without interfering with each other.

But everyone who has developed a little web page knows how to establish a connection between JavaScript and scrolling:

When we add the wheel's listening process, which calls

The effect of such an example is less obvious:

You may naively think that if a function does not call

Listening to the mouse wheel does not interact with our large blocking JavaScript operation, but they have a common event loop, so the background thread must wait for the longer JavaScript operation to complete before it receives a response from the event listening function.

Why should he wait? Well, JavaScript is a dynamic programming language, and the browser cannot know for sure that

Please note that this applies not only to the mouse wheel: on touch devices, scrolling can also be blocked by listening to touchstart or touchmove processes .

You need to be careful when adding listening events to the page, because they affect performance!

There are several javascript APIs associated with scrolling, however they do not block scrolling. The scroll event, although this is somewhat illogical, cannot block the scrolling, because it starts after scrolling, and therefore is irreducible. Also, the new Pointer Events API , introduced in IE and Microsoft Edge, and which has recently begun to be implemented in Chrome and Firefox, was originally designed to avoid inadvertently blocking scrolling.

Even in cases when we really need to listen to wheel or touchstart events , there are certain tricks on how web developers can guarantee the scrolling operation with maximum quality. Look at some of these tricks.

In the previous example, we saw a case of a global listening process (that is, attached to a window or document ). But what about listening processes for individual scrolling elements?

In other words, imagine the page for which scrolling works, but on the page there is a separate area with its own independent scrolling. Does the browser block scrolling for the entire page if you add a listening process only in this area?

If you check on a simple demo page , you will notice that Microsoft Edge and Safari will leave a smooth scrolling for the whole document if the listening process for scrolling is in a div with independent scrolling.

Here is a table of browsers and their behavior:

The results show * that there are optimizations available for web developers to benefit from these browser features. Instead of using wheel / touch listening processes for the entire document, it is preferable to add listening processes to a specific subsection of the document , so the scrolling will remain smooth for all other parts of the page. In other words, instead of delegating wheel / touchstart listening processes to the highest possible level, it is best to isolate them for the element where it is needed.

Unfortunately, not all JavaScript frameworks allow this practice - in particular, React, as a rule, adds a global listening process to the entire document, even if it should apply only to part of the page. However, there is an open ticket specifically for this problem, and the React guys said that they will gladly accept a pull request. (Respect the guys from React, who so quickly responded to our proposal )

Avoiding global wheel / touchstart listening processes is a good practice, but sometimes this is simply not possible, depending on the effect you are trying to achieve. And in some ways it looks silly that simply listening to events causes the browser to stop the whole world, simply because there is a hypothetical probability of calling

Fortunately, a new feature began to appear in browsers when web developers can explicitly mark the listening process as “passive” and therefore avoid waiting:

With this approach, the browser will handle the scrolling as if the wheel listening process is completely absent. This feature is already available in the latest versions of Chrome, Firefox and Safari, and should soon appear in the future release of Microsoft Edge . (Please note that you need to use feature detection to support browsers that do not recognize passive listening processes).

For some events (including touchstart and touchmove ), Chrome from version 56 decided to interfere and made them passive by default . Keep in mind this slight difference between browsers when adding listening processes!

As we have seen, scrolling on the web is a fantastically complex process, and all browsers are at different stages of improving their performance. But in general, we can formulate some clear tips for web developers.

First, it is better not to add the wheel or touch listening processes to the global document or window objects, but instead to add them to smaller elements with individual scrolling. Developers should also use passive listening processes, wherever possible, using feature detection to avoid compatibility issues. Using Pointer Events (there is a polyfill there ) and scroll listening events are also a sure way to avoid inadvertently blocking scrolling.

I hope this article has provided some useful tips for web developers and allowed a glimpse of what browsers have under the hood. Without a doubt, as browsers develop and the web grows, the scrolling mechanics will become even more complex and sophisticated.

Our Microsoft Edge team will continue to innovate in this area to ensure smooth scrolling for more sites and users. Let's say this for a modest scrollbar - the oldest and ambiguous interaction on the web!

* Results are obtained on the latest version of each browser in February 2017. Since then, Firefox 52 has updated support for scrolling, and now matches the behavior of Edge 14 in all tests, with the exception of scrolling by the scroll bar. Hopefully, other browsers will also make scrolling improvements and make the web faster and more responsive!

Scrolling is one of the most ancient interactions on the web. Long before the advent of the pull-to-refresh methods and endless download lists, the modest scroll bar solved the initial scaling problem on the web: how to interact with content that extends beyond the available viewing area?

Today, scrolling is still the most fundamental interaction on the Web, and perhaps the most misunderstood. For example, do you know the difference between the following scenarios?

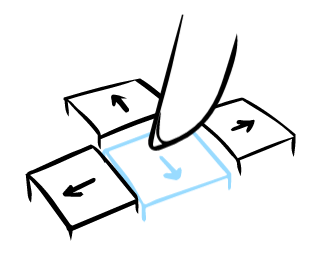

- User scrolls the page with two fingers on the touchpad

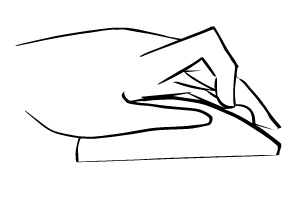

- User scrolls with one finger on the touchscreen

- User scrolls the mouse wheel

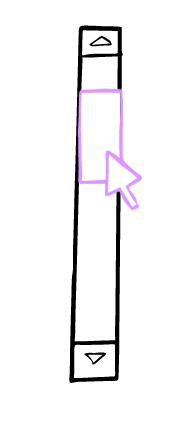

- User clicks the scroll bar and pulls it down and up

- The user presses the up, down, PageUp, PageDown and space bar on the keyboard

If you ask the average Internet user (or even the average web developer!), They can tell you that these actions are equivalent. The truth is much more interesting.

As it turns out, these five input methods have very different characteristics, especially in terms of performance and cross-browser compatibility. Some of them (like scrolling on the touchscreen) are likely to be smooth even on a page using heavy javascript, while from others (like scrolling from the keyboard) the same page will lag and become insensitive. Moreover, some types of scrolling can be slowed down by DOM event handlers, while others cannot. What's going on here?

')

To answer this question and understand how to implement the smoothest scrolling for your site, let's step back to understand and see how browsers deal with multithreading and input.

Multithreaded web

Conceptually, the web is a single-threaded environment. JavaScript blocks DOM, and DOM blocks JavaScript, because both are fighting for the same thread, often called the “main thread” or the “UI thread”.

For example, if you add this (horrible) JavaScript snippet to a page, you will immediately notice a deterioration in performance:

setInterval(() => { var start = Date.now(); while (Date.now() - start < 500) {/* wheeeee! */} }, 1000); While this JavaScript is spinning in an infinite loop, the buttons do not work, the elements of the forms do not react and even the animated GIFs slow down - in all senses and relationships, the page is frozen. You can study the effect in action in a simple demo .

Moreover, if you try to scroll the page with the "up" and "down" keys on the keyboard, the page is predictably stuck until JavaScript stops running. All this is clear evidence of our presentation of the web as a single-threaded environment.

There is a funny anomaly: if you try to scroll through the touchscreen, the page scrolls up and down perfectly, although JavaScript blocks everything else on the page. The same applies to scrolling from the touchpad, mouse wheel and scrolling after the page is captured with the click-and-drag cursor (depending on the browser).

Somehow, some scrolling actions can change the state of the page, while everything else — buttons, data entry fields, GIFs — is completely frozen. How can we combine this with our single-threaded web theory?

The history of two threads

As it turns out, in general, the thesis “single-threaded browsers” is true, but there are important exceptions. Scrolling, in all its diversity, is one such exception.

Over the years, browser developers have realized that unloading auxiliary work into background threads can provide significant benefits in terms of smoothness and sensitivity. Scrolling is so important for a key browser experience that this task was quickly chosen for this optimization. Nowadays, all the major browser engines (Blink, EdgeHTML, Gecko, WebKit) support scrolling beyond the main thread of execution to one degree or another (Firefox was the last to join the club, from Firefox version 46 ).

With background scrolling, even a cluttered page will scroll smoothly, because all scrolling is performed in a separate thread. Only if you try to interact with the page through some extraneous mechanism that is not related to scrolling - press a key, enter data in the input field, click on the link - then the facade is reset and the essence of the salon stunt fully reveals itself. (Considering how well it works, this is a great trick!)

True, asynchronous scrolling has a common side effect, which is called the checkerboard effect . It first appeared on the Safari for iOS in the form of gray and white cells, as if from a chessboard. In most modern browsers, the effect appears as empty space on the screen if you scroll faster than the browser can render the page. This is not ideal, but it is an acceptable compromise compared to a locked, jerking or non-replicable scrolling.

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to transfer scrolling to a background thread. Browsers can do this only if the operating system allows simultaneous input, and this may vary from device to device. In particular, keyboard input is not as optimized as mouse or touch device input, which ultimately leads to more significant lags when typing from the keyboard in all browsers.

There will be an instructive little story. When operating systems like Windows and macOS first came out, they allowed only one thread of execution, and very few people foresaw the need to provide for simultaneous input. It was only when multi-core machines appeared that the operating systems began to build parallelism into their architecture.

Just as the rudimentary organs of animals make their evolutionary history understand, the single-threaded origin of operating systems manifests itself when looking at how to scroll on the web. Only if the operating system allows parallel input — from a mouse, keyboard, or other device — can browsers effectively optimize scrolling so that it is not affected by the lengthy execution of JavaScript that has trapped the main thread of execution.

However, in the Microsoft Edge development team, we are making progress to ensure smooth and responsive scrolling, regardless of its method. In EdgeHTML 14 (which is included with Windows 10 Anniversary Update), we support background scrolling for the following methods:

- One finger, touchscreen

- Two fingers, touchpad

- Mouse wheel

- Scroll bar

If you compare Edge with other desktop browsers, you'll notice that only it supports asynchronous scrolling using the scroll bar, i.e., holding and moving the scroll slider with the mouse, clicking on the scroll bar or arrows. (Actually, we presented this feature without the announcement back in the Anniversary Update!)

According to the test results in Windows 10 (14393, Surface Book) and macOS Sierra (10.12, MacBook Air), we got the following results:

| Two finger touchpad | Tach | Mouse wheel | Scroll bar | Keyboard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge 14 (Windows) | there is | there is | there is | there is | Not |

| Chrome 56 (Windows) | there is | there is | there is | Not | Not |

| Firefox 51 (Windows) | Not | Not | Not | Not | Not |

| Chrome 56 (MacOS) | there is | N / A | there is | Not | Not |

| Firefox 51 (MacOS) | there is | N / A | there is | Not | Not |

| Safari 10.1 (MacOS) | there is | N / A | there is | Not | Not |

As this table demonstrates * , scrolling behavior can dramatically change from browser to browser, and even from one OS to another. If you test one method of scrolling in only one browser, you will get very incomplete results of the performance of your site, compared to how users actually work with it!

In general, it should be clear that scrolling has a special place on the web and browsers work very hard to make it fast and responsive. However, there are subtle ways that a web developer can inadvertently disable browser optimizations. Let's look at how web developers can influence the scrolling in the browser, in an amicable and bad way.

How listening processes interfere with scrolling

Background scrolling gives a tangible increase in efficiency - scrolling and JavaScript are completely separate, allowing them to work in parallel without interfering with each other.

But everyone who has developed a little web page knows how to establish a connection between JavaScript and scrolling:

window.addEventListener(“wheel”, function (e) { e.preventDefault(); // oh no you don't! }); When we add the wheel's listening process, which calls

event.preventDefault() , it blocks scrolling 100% for both the mouse wheel and the touchpad. And obviously, if scrolling is blocked, then background scrolling is also blocked.The effect of such an example is less obvious:

window.addEventListener(“wheel”, function (e) { console.log('wheel!'); // innocent listener, not calling preventDefault() }); You may naively think that if a function does not call

preventDefault() , then it cannot block scrolling at all or, in the worst case, blocks it only for the duration of the function itself. However, the truth is that even an empty listening process completely blocks scrolling until all the JavaScript processes on this page are finished, which you can check out in this demo .Listening to the mouse wheel does not interact with our large blocking JavaScript operation, but they have a common event loop, so the background thread must wait for the longer JavaScript operation to complete before it receives a response from the event listening function.

Why should he wait? Well, JavaScript is a dynamic programming language, and the browser cannot know for sure that

preventDefault() will never be called. Even if it’s obvious to the developer that the function is simply recording console.log() , browser developers prefer not to leave chances. In fact, even an empty function() {} will cause the same effect.Please note that this applies not only to the mouse wheel: on touch devices, scrolling can also be blocked by listening to touchstart or touchmove processes .

You need to be careful when adding listening events to the page, because they affect performance!

There are several javascript APIs associated with scrolling, however they do not block scrolling. The scroll event, although this is somewhat illogical, cannot block the scrolling, because it starts after scrolling, and therefore is irreducible. Also, the new Pointer Events API , introduced in IE and Microsoft Edge, and which has recently begun to be implemented in Chrome and Firefox, was originally designed to avoid inadvertently blocking scrolling.

Even in cases when we really need to listen to wheel or touchstart events , there are certain tricks on how web developers can guarantee the scrolling operation with maximum quality. Look at some of these tricks.

Global and local listening processes

In the previous example, we saw a case of a global listening process (that is, attached to a window or document ). But what about listening processes for individual scrolling elements?

In other words, imagine the page for which scrolling works, but on the page there is a separate area with its own independent scrolling. Does the browser block scrolling for the entire page if you add a listening process only in this area?

document.getElementById('scrollableDiv') .addEventListener(“wheel”, function (e) { // In theory, I can only block scrolling on the div itself! }); If you check on a simple demo page , you will notice that Microsoft Edge and Safari will leave a smooth scrolling for the whole document if the listening process for scrolling is in a div with independent scrolling.

Here is a table of browsers and their behavior:

| Two finger touchpad | Tach | Mouse wheel | Click-and-drag | Keyboard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desktop Edge 14 (Windows) | there is | there is | there is | there is | Not |

| Desktop Chrome 56 (Windows) | Not | there is | Not | Not | Not |

| Desktop Firefox 51 (Windows) | Not | Not | Not | Not | Not |

| Desktop Chrome 56 (MacOS) | Not | N / A | Not | Not | Not |

| Desktop Firefox 51 (MacOS) | there is | N / A | there is | Not | Not |

| Safari 10.1 (MacOS) | there is | N / A | there is | Not | Not |

The results show * that there are optimizations available for web developers to benefit from these browser features. Instead of using wheel / touch listening processes for the entire document, it is preferable to add listening processes to a specific subsection of the document , so the scrolling will remain smooth for all other parts of the page. In other words, instead of delegating wheel / touchstart listening processes to the highest possible level, it is best to isolate them for the element where it is needed.

Unfortunately, not all JavaScript frameworks allow this practice - in particular, React, as a rule, adds a global listening process to the entire document, even if it should apply only to part of the page. However, there is an open ticket specifically for this problem, and the React guys said that they will gladly accept a pull request. (Respect the guys from React, who so quickly responded to our proposal )

Passive listening process

Avoiding global wheel / touchstart listening processes is a good practice, but sometimes this is simply not possible, depending on the effect you are trying to achieve. And in some ways it looks silly that simply listening to events causes the browser to stop the whole world, simply because there is a hypothetical probability of calling

PreventDefault() , and it is waiting for it.Fortunately, a new feature began to appear in browsers when web developers can explicitly mark the listening process as “passive” and therefore avoid waiting:

window.addEventListener(“wheel”, function (e) { // Not calling preventDefault()! }, { passive: true } // I pinkie-swear I won't call preventDefault() ); With this approach, the browser will handle the scrolling as if the wheel listening process is completely absent. This feature is already available in the latest versions of Chrome, Firefox and Safari, and should soon appear in the future release of Microsoft Edge . (Please note that you need to use feature detection to support browsers that do not recognize passive listening processes).

For some events (including touchstart and touchmove ), Chrome from version 56 decided to interfere and made them passive by default . Keep in mind this slight difference between browsers when adding listening processes!

Conclusion

As we have seen, scrolling on the web is a fantastically complex process, and all browsers are at different stages of improving their performance. But in general, we can formulate some clear tips for web developers.

First, it is better not to add the wheel or touch listening processes to the global document or window objects, but instead to add them to smaller elements with individual scrolling. Developers should also use passive listening processes, wherever possible, using feature detection to avoid compatibility issues. Using Pointer Events (there is a polyfill there ) and scroll listening events are also a sure way to avoid inadvertently blocking scrolling.

I hope this article has provided some useful tips for web developers and allowed a glimpse of what browsers have under the hood. Without a doubt, as browsers develop and the web grows, the scrolling mechanics will become even more complex and sophisticated.

Our Microsoft Edge team will continue to innovate in this area to ensure smooth scrolling for more sites and users. Let's say this for a modest scrollbar - the oldest and ambiguous interaction on the web!

* Results are obtained on the latest version of each browser in February 2017. Since then, Firefox 52 has updated support for scrolling, and now matches the behavior of Edge 14 in all tests, with the exception of scrolling by the scroll bar. Hopefully, other browsers will also make scrolling improvements and make the web faster and more responsive!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/325028/

All Articles