Where the games go: the problem of preserving old video games. Part 2

Aftermath of the Kobe earthquake

[Part 2 of the article describes how video games can be protected from natural disasters and impacts. Museums and video game archivers explain their goals and ask industry representatives to send them artifacts. At the same time, Japan is struggling to open its own video game museum in a political conflict. Part 1, which deals with the amazing fate of Atari and Sega’s historical material, can be found here .]

In August 1986, Konami opened the Konami Software Development building in the Minatojima district of Kobe, Japan. That same year, Hideo Kojima, the creator of the Metal Gear Solid series, joined the company. The building in Kobe has adopted development teams that will then create the most popular series of Konami games. Development department 5 was one of such departments. It consisted of ten people, one of which was Hideo Kojima himself.

')

On the morning of January 17, 1995, Kobe was shaken by the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. It was the strongest earthquake in Japan. 6,434 people died, an earthquake caused damage of about 102.5 billion dollars.

The building of Konami Software Development was one of the buildings in Kobe that were affected by the disaster. Kojima told how the earthquake affected him personally and his colleagues from the development department 5 in the post Kojima Productions Report .

In July 2007, at an event in honor of the anniversary of Metal Gear , a video was shown about the experiments of Kojima and his team with the early Sony PlayStation technology in the winter of 1995, when the Kobe earthquake occurred.

This video describes how the 5 Konami development department lost a huge amount of data and hard work. The earthquake forced the team to move offices to the Ebisu area in Tokyo and start from scratch. Employees laid out from Lego preliminary level schemes for the game, which later will turn into Metal Gear Solid on Sony PlayStation.

Fortunately, according to Kojima's latest tweets, it turned out that some of the early Metal Gear design documents are preserved. Messages are collected in Kotaku and Hachimaki .

According to IGN, Konami also lost most of the original Castlevania graphic works created during the earthquake.

Damage to the Konami Software Development building is documented in the official corporate history of Konami. We contacted Konami Digital Entertainment in Tokyo to clarify the loss of engineering materials from the Kobe earthquake. Konami's public relations department politely declined to comment, citing the company's policy of non-disclosure of game development information.

In the video game conservation questionnaire sent to developers and publishers to write this article, Sony Computer Entertainment of America was one of the respondents who expressed the need to store development tools, equipment and game data in disaster-proof archives.

In many industries: medical, legal, entertainment and manufacturing, a common way to prevent damage from natural disasters is used: underground storage in a salt mine. Underground Vaults & Storage is a specialized company that provides six vaults to customers from around the world. One of the repositories is located in Hutchinson, Kansas. It has been used for over fifty years. The room is located 200 meters below the surface of the earth, access to it is possible only through secure elevators.

It is reported that in this repository are the negatives of films of large Hollywood film studios. It contains the original negatives of Star Wars, Ben Gura, Gone with the Wind, and Journey to the Center of the Earth. In two months, 20th Century Fox transported twenty-two trucks with originals of negatives there.

“The natural underground environment is ideal for storage — a constant temperature of 20-21 degrees Celsius and 50 percent humidity,” says Jeff Ollenburger, business development and sales manager for Underground Vaults & Storage.

“Many of our clients have realized that they can safely, and, importantly, economically store their archives with us for decades without occupying precious space in their premises. If after 20 years they need this information, they can easily extract it, ”says Allenburger

Ollenburger has no right to talk about his clients, including developers and publishers of video games, but says that they are always welcome. "Any organization, including the video game industry, which is interested in storing information and archival materials, should keep them in one of the most protected places on the planet."

Another protected organization in which developers and publishers of video games can search for their materials that were considered lost - the United States Copyright Office. Over the past several decades, many developers and publishers have placed source code listings there, while others have made “identifying materials posted instead of games”, such as videotapes or a textual description of the gameplay.

Despite the fact that Irem admitted when polling in the absence of the source code of their games created in the 1980s, when searching the US Copyright Office found the source of the games Irem. A listing has been found of what is supposedly the source code for several Irem games, including 10-Yard Fight , Red Alert, and Super R-Type .

However, it is not clear how complete this code is, because for the registration of copyright on a computer program, the Bureau requires the first 25 and last 25 pages of the source code, or the entire code, if it is less than 50 pages. Printouts of source code containing trade secrets may also be closed under certain circumstances.

Despite this, it should be noted that these vaults are protected and can only be accessed with the written permission of the applicant for rights, the authorized agent of the applicant or the owner of any exclusive rights.

There is another area of game conservation that is becoming increasingly important: you can call it a “safe haven” for video game artifacts. Such a haven in recent years is growing rapidly. This became apparent when one company, Fairchild Semiconductor, mentioned a museum where research was carried out for my article.

Fairchild Semiconductor was once a manufacturer of video game consoles. In 1976, she developed the first video game system with ROM cartridges called Fairchild Channel F. The company, founded in 1957, was bought up many times, and in 1987 it completely disappeared. Ten years later, Fairchild Semiconductor began work again, but this time in Portland, Maine.

“Most of the historical information has disappeared over the years. I have a few photos and newsletters of the company, but nothing has survived on video games, ”commented Patty Olson of Fairchild Semiconductor Corporate Communications. Olson directed us to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. In an online search through their archives, we found the photographed artifacts of the game consoles Fairchild Channel F and Channel F II.

Artifacts of games from computers, consoles and arcade machines have found their home - the house, whose collection is growing rapidly.

Carefully looking at the efforts of video game archivers, you can see the work on cataloging and archiving all aspects of video games. This work has intensified in the past five years thanks to the collections stored in major universities and museums.

These collections of artifacts are available to researchers and teachers, many are shown to a wide audience at special exhibitions. Specialized organizations are constantly looking for exhibits related to the gaming industry, exhibits that are desperately in need of preservation.

In addition to the Computer History Museum in California, there are also collections of the history of science and technology, film and media collections located in the libraries of Stanford University under the direction of Henry Lovewood and his colleagues.

Lovewood is the leader of the project “How They Have a Game: the History and Culture of Interactive Simulations and Video Games”, founded in 2000. Lovud is also the chairman of the International Game Developers Association ad hoc group on game conservation .

Since 2008, Lovewood has been one of the main researchers in the major project " Preserving Virtual Worlds " sponsored by the Library of the US Congress. Organizations working with this project include Linden Labs, The Internet Archive, and several well-known universities.

The goal of the project is to research ways of preserving virtual interactive worlds and multi-user environments. The “Preservation of Virtual Worlds” project released a final report to the general public at the end of August 2010.

Heading east from California, you can visit the expanding video game archive at the University of Texas at Austin. The UT Video Game Archive was founded here as part of the collection of the American History Center Dolph Briscoe. The first three sponsors of the archive were veterans of the gaming industry, Richard Garriot (Richard Garriot), Warren Spector (Warren Spector) and George Sanger (George Sanger).

According to archivist Zack Wouell, he helped create fourteen collections, including the first game of Richard Garriott Akalabeth and design documents for the Ultima series. Woell was considering offers of donations of artifacts, and now he is actively looking for "not only gaming software and equipment, but also documents, illustrations, digital recordings, promotional materials and business archives related to video games."

Visitors rated two dozen classic coin arcade machines on display in ICHEG. ICHEG now stores more than 120 arcade machines. The collection database is available on the ICHEG website .

Moving to the northeastern United States, you can visit the exhibition at the International Center for Electronic Games (ICHEG), based at the National Strong Games Museum in Rochester, New York. It seems that ICHEG holds the world's largest collection of electronic games and game-related historical materials. It presents more than 20 thousand electronic games, platforms and materials.

ICHEG opened its eGameRevolution exhibition to the public in November 2010. The exhibition occupies 460 square meters, it presents a genuine video game arcade room with two dozen classic arcade machines. Various exhibits demonstrate the beginning of the history of the gaming industry. The exhibition also has home PCs and consoles, allowing visitors to play classic games.

Close-up of the showcase on eGameRevolution with various video game artifacts from ICHEG.

ICHEG has Twitter and Facebook accounts with news about ICHEG events, as well as its own blog . Chronicles of game preservation work are maintained on a blog by ICHEG staff, including John-Paul Dyson, (Jon-Paul Dyson), director of ICHEG. Among the latest donations are personal papers by Will Wright and artifacts from the family of game designer Dani Bantin Berry who left us.

Dyson showed us a post on the ICHEG blog that Europe is also taking steps to save video games. “Archivio Videoludico in Bologna creates a collection of video games available to researchers and the public. In Rome, the video game museum ViGaMus opened a public exhibition in 2011. " [Approx. Trans .: article written in 2011.]

ICHEG also sends artifacts to Germany, where they will be temporarily given to Computerspiele Museum, which opened a permanent exhibition in Berlin in January 2011. Computerspiele Museum demonstrated the design concept of its exhibition on the website and on the official YouTube channel .

Another important European organization dedicated to the preservation of games is the National Video Games Archive (NVA), a joint project of the National Museum of Media and the Center for Contemporary Games at the University of Nottingham.

NVA is actively seeking dialogue with the gaming industry about the preservation of all game elements in the UK. These discussions take place at a special NVA summit during the annual GameCity festival in Nottingham.

NVA launched the Save the Video Game campaign, which has already attracted industry attention and donations of artifacts from developers, including Sony and Rockstar. NVA and Save the Video Game are managed by Prof. James Newman, Iain Simmons and Tom Woolley.

NVA also has an Games Lounge at the National Media Museum. NVA continues to explore the demonstration of its collections in the UK. Recently, the British Library expressed interest in collaborating with NVA.

For this article, Lovewood, Wowell, Dyson and Newman answered a few questions. Is it possible to hope that the participants of the video game industry (programmers, designers, directors and producers) have stored in their archives a long-forgotten source code and game development artifacts?

Moreover, should veterans of the games industry invest efforts in transferring these objects to museums, universities and source code preservation projects?

Henry Lovewood, curator of the collections of the history of science and technology at Stanford :

“You can not only hope for it, it is already happening in reality. In fact, individual employees (from private officers to heads of laboratories, as well as just to whom interesting objects happened to be) have always been the main source of archival collections, such as the Stanford Archives of Silicon Valley. Archives of games originated in a similar way, for example, from Spector's documents at the University of Texas or from Meretzka's documents at Stanford. ”

“There are two big differences between private collectors and industry veterans as opposed to cultural repositories, such as libraries and museums. First, employees of companies can get access to objects closed to organizations. Secondly, people are mortal, and organizations continue to live. One of the main tasks in my position is to link the common interests of these two groups. It is mutually beneficial for them to work together. ”

Zach Wowell, Archivist, University of Texas Video Game Archive :

“I answer“ yes ”to both questions. The situation you described in the first question fully corresponds to the way the University of Texas Video Game Archive was formed. Richard Garriott, Warren Spector and George Sanger contacted us and transferred materials accumulated over many years. They did not want this documentation to be lost or forgotten. ”

“Since then, many developers have contributed materials to our archive. So this can and does happen. To be honest, due to tight control over intellectual property, it’s most likely that the personal collections of developers with documentation will be the main source for expanding our archives, at least in the initial stages. ”

“I urge all industry veterans with collections of documentation, games, consoles, magazines to at least contact us or other repositories. If the materials are not subject to disclosure (for example, under the terms of the contract), we can impose reasonable restrictions until the moment of the legal possibility of disclosing materials for research, exhibitions and public access. ”

John-Paul Dyson, director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games :

"Some veterans of the gaming industry retain their materials, but, unfortunately, I very often met people who regretted the loss of many of the materials on which they worked."

“In general, this is becoming an increasing problem, because in the process of producing games there are less and less physical aspects. Game designers of the past often made prints of code and design concepts, but in modern game creation environments such physical artifacts are less and less likely, and many game designers often do not save fully digital resources when they leave the company. ”

“Yes, I believe that if veterans of the gaming industry are interested in preserving their work, they should post materials to relevant organizations that can save them for a long time. Organizations can guarantee long-term storage and also provide access for researchers hoping to understand the industry’s history. Too often, materials left in the hands of private individuals do not survive due to natural disasters, are thrown away, or are not stored by heirs. ”

Professor James Newman, National Video Game Archive

“We would like to think so. NVA was created in response to requests from the video game industry. It is worth repeating that we deal not only with code. We strive to tell the story of video games in all its contexts. We are interested in players with their perception of games, and the role of games in popular culture. ”

"Therefore, despite the fact that developers donate rare and even unique objects to the NVA collection, we must remind ourselves that everyday, ordinary parts of gaming culture or game development are just as important for transmitting the game history to future generations."

“We don’t say that the mass-produced Pikachu toys are just as valuable as the prototypes of Rock Band controllers or the pre-sale version of the EyeToy camera, but all of these objects are important parts of the video game history. There is a tendency to preserve large, impressive objects, what everyone considers important, and everyday things disappear forever. ”

Newman highlights the main goal of NVA, which is shared by most modern video game archives:

“Preserving the code base is only one part of our work, so our archival works extend to many other aspects. — , , , , , , , ».

« , , , , , . , , . — , ».

— , . — -.

, : « ( ) , , Advanced Tactical Fighters ( ). , , , ( ) ».

«, - Ion Storm , , ( — )».

: - . . JET (Japan Exchange Teaching Program), («International Video Game Museum») .

2005 - . , .

- 2006 . 2008 , .

, , . (National Center for Media Arts, NCMA), Japan Times.

NCMA , , , . . 2009 , NCMA 11,7 (132 ).

, NCMA - ( , ). 930 .

, , « -». , , NCMA, -. , 2009 102 , , , , . Japan Times . :

"… NCMA - . ".

NCMA . NCMA, , , , , ( ) — , — .

Japan Times, 2009 , 28- , Realthing Inc., . - , , NCMA :

« 20 … , , ».

: «, . », — .

- Japan Times - , - 54 .

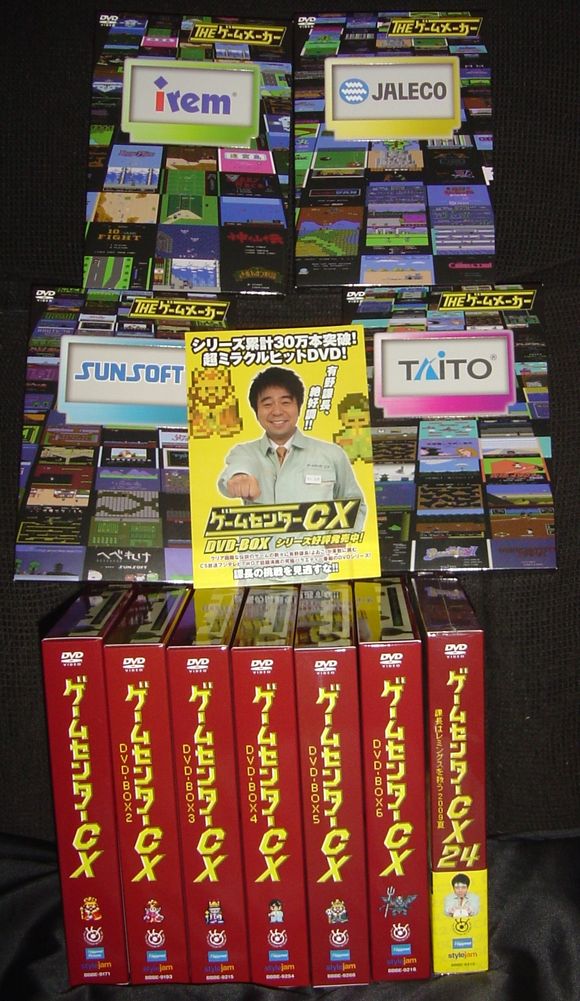

GameCenter CX . . -

- NCMA. .

, . , 2006 , . — -- 2010, 16 . , , 2010, 10 .

, , -. NCMA , , .

250 (2,3 ), , ( ). CESA.

— , 2014 « ». , , . , -. .

, . , , , .

Nintendo Famicom. Game Archive Project 1998 .

— - .

Game Archive Project Nintendo: Game Archive Project, 1300 . Sega, .

Game Archive Project , , .

Game Archive Project « ». -.

: , . Project Egg — , . 600 PC-9801, FM-7 X68000.

: , . , .

, — , - . , : - , , , .

, Moby Games GameFAQs . , , .

, , . . , , , .

Parker Brothers, Maxis, Capcom, American Technos Gametek Consumer Electronics Show (CES) 1992 . Matchbox Video Games 1990 ( ) CES, NES, Matchbox, Matchbox Racers , Motor City Patrol , EuroCup Soccer , Sir Eric The Bold Noah's Ark . Matchbox Video Games, , , Matchbox.

, , , , . ( ), , .

, , , Atari Corporation, . : .

— , , . , « . » . . 1995 29 . , .

, . , , . , .

, , « » . , , . , , .

— — . — , , . , , .

— , , .

, , . . ? , ? , ?

. . - , , , .

, , , . , - , , , .

, , , . , , , «Start», .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/323620/

All Articles