Voice standards

Whenever you pick up the phone, remember: magic happens inside. Just imagine that every hertz of a warm human voice is processed, modulated, transformed and transmitted thousands of kilometers. Small streams of individual conversations merge into huge rivers of highways and again break up into separate conversations between man and man.

And all this is due to the standards.

“Why do we need standards?” - the reader will ask, far from telecoms. And we will answer: standards are necessary for the market to develop. So that the telephone system could understand another telephone system and connect one device with another, even if subscribers are located in different hemispheres. Without following the standards of telecommunication companies, this simply would not have happened - imagine that in Russia there is one way to code telephone addressing, and in the American company AT & T another. Telephone systems simply could not “agree” among themselves, and you could not communicate with your overseas uncle (and would remain without an inheritance).

')

And of course, the standards did not appear immediately. As telephone equipment developed, they expanded and multiplied, gradually transforming into a modern system for establishing connections based on the “common channel signaling” Signaling System No. 7, or in Russian ACS-7.

Moreover, OKS-7, despite its perfect universality, is rapidly becoming outdated standard - with the development of IP networks, it is replaced by completely different principles of subscriber search / selection and communication. But at the same time, the penetration of ordinary telephony and the user habits associated with dialing are still too significant to abandon its use.

Therefore, the standards of voice connections are still relevant and even develop together with the mass introduction of technologies under the common name “voice over packet networks” - Voice-Over-IP (the more familiar is the abbreviation VoIP ).

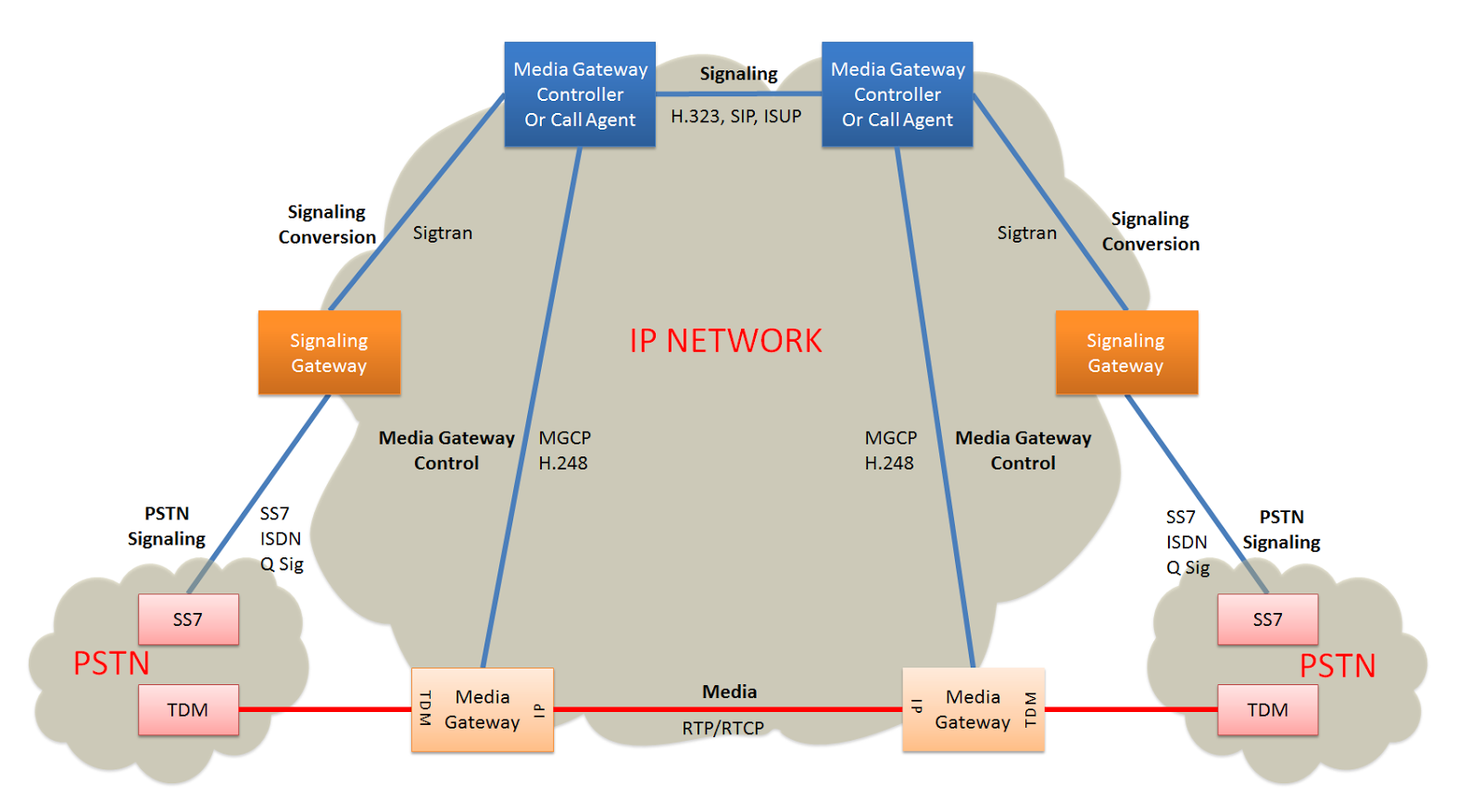

Nevertheless, all these standards are connected with the historical heritage of public switched telephone networks (Public Switched Telephone Network - PSTN), for which numerous media gateways (Media Gateway - serve to transform media traffic) and signaling gateways (Signaling Gateway - for transformation signaling and switching protocols).

All this has led to the fact that modern voice networks look quite complicated and confusing. For example, like this.

There are at least two driving force standards:

- The International Telecommunication Union - ITU (Eng. International Telecommunication Union, ITU), which has existed since 1865, that is, even before the advent of telephony.

- And the “telecommunications community” represented by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is an organization with an uncertain legal status (everything is difficult there — in fact, it is an open independent international organization that is a subsidiary of ISOC, the Internet Society Internet Society, ISOC)).

The International Telecommunication Union is a bureaucratic international monster, in fact the structure of the United Nations. It is believed that the directives adopted at the ITU meetings will be binding throughout the world. At the same time, the IETF is a very flexible and mobile community of telecom professionals who simply write documents describing technologies, specifications and standards and offer them for discussion and, if the community accepts the document, for widespread adoption.

And this is quite a simple case of trying to make friends with good old telephony and fully digital voice communications.

Anyway, at present, all telephone conversations, with the exception of very old telephone exchanges within an enterprise or a small settlement, are transmitted in digital form. It's just that it's cheaper and more efficient.

But let's move on to the standards.

ITU recommendations

The structure of the International Telecommunication Union, as with all organizations on a global scale, is very complicated. But this is not surprising: ITU includes 193 states (virtually all) and more than 700 member organizations — these are the largest enterprises: equipment developers, telecom operators, and research institutes. At present, there are three large sectors in the ITU structure, where working groups are already organized in areas and / or technologies:

- ITU-T (ITU-T) - telecommunication standardization sector;

- ITU-R (ITU-R) - the radiocommunication sector;

- ITU-D (ITU-D) - telecommunication development sector.

We, of course, are interested in ITU-T - the standardization sector, which produces the international standards proper, which are called “Recommendations” (Recommendations - with a capital letter, to emphasize their importance and to distinguish from simple recommendations). But it must be understood that no state will undertake to unconditionally comply with international standards, especially if they contradict national interests and / or the general development of technology. That is why we are talking about Recommendations, and not about obligations, that is, if a state that has not adopted the standard wants to communicate with other states, it must to a certain extent adopt international standards that are recommended for implementation.

Since ITU-T is a part of ITU, and ITU is a specialized agency of the United Nations, standards from ITU-T are more formal and undoubtedly have more international weight than standards of other standardizing technology organizations. And that is why standards appear with very serious delays in time - too many interests need to be taken into account when developing and approving Recommendations.

For example, the well-known fact about the development of the “seven-level OSI network model”, on which work began in ITU-T in 1978, but the final approved document under the code X.200 was released only in 1994. More flexible standards in the form of the usual TCP / IP protocol stack evolved much faster.

But in terms of telephony, of course, the standards from ITU-T are more authoritative than anything else. Simply the fact that the International Telecommunication Union was created several years before the advent of telephone communication in general, already obliges.

So, ITU-T standards for telephony are described in the following sections:

- ITU-T Series E: Overall network operation, telephone service, service operation and human factors - “Operating conditions for networks and telephone services”, where, perhaps, the most important today is the E.164 standard - “Telephone Numbering Plan” .

- Quite an extensive H series: Audiovisual and multimedia systems - “Audiovisual and multimedia systems”. For telephony, the H.323 series is the most important here - Recommendations defining a set of standards for the transfer of multimedia (not only voice information) over data networks. And be sure to mention H.248 - a whole series of Recommendations that describes the interaction protocols between gateways and gateway controllers.

- G- Series : Transmission Systems and Media Systems, Digital Systems and Networks - Digital Media Transmission Systems. The most used in telephony is Recommendation G.711 - a standard for the transmission and compression of voice data in digital networks. The most common codec in telephony is BCC (main digital channel). But in general, the G series describes in some detail practically all the ways to establish voice communication - from international connections (G.100-199 series) to networks of the new generation NGN or description of the time format in networks, for example, GeneralizedTime.

- Series Q: Switching and signaling - “Switching and signaling”. Actually, this section sets the standards for the SS-7 signaling system. For example, Recommendation Q.7 describes the previous alarm systems for establishing telephone connections in automatic and semi-automatic mode — SS.4 (1954), SS.5 (1964), SS.6 (1968) and the transition to SS.7 ( since 1980). Actually SS-7 - this is the whole Q series, especially in versions of Q.7xx.

Target group of Internet engineers

Developers from the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), in terms of defining standards, went a little different way - as free from bureaucracy as possible, and therefore more flexible and faster. At the same time, IETF standards are not even called standards - this is Request for Comments (RFC). If you literally translate, you get "request for comments" or a more accurate translation - "topic for discussion." In the Russian-speaking environment, they are more often called the “working proposal”.

And as a matter of fact, the RFC is not a standard document, binding. But the weight of the IETF community is so great that the actual adopted RFCs somehow become standards. For example, including the ITU-T quite often takes the RFC as the basis for the approval of the standard itself.

The procedure for writing RFC standards is quite simple — you can try writing your own RFC and can even accept it. RFC statuses through the chain:

- Internet Draft - Internet draft standard, which is submitted for universal approval. If within six months no one has made any changes and there has been no discussion of the proposal, the document is deleted.

- Proposed Standard - the status of the proposed standard document receives, if the project is supported by the community of editors. The document is assigned its own RFC number.

- Draft Standard - draft standard. This is a higher status, which means that the proposed standard is not only adopted, but also being developed and implemented by at least two independent teams. Minor changes may be made to standards, but these solutions are considered to be quite stable.

- Internet Standard is an Internet standard. The highest status of RFC is the de facto accepted standards that all developers use.

- Historic - if the standard is outdated and replaced with new forms, then this document is assigned the status of "historical".

As of this writing, 9805 documents in all statuses have been published in the IETF catalog. This is a lot. However, the status of Internet Standard received about 50 documents. At the same time, there are no “high-standard” documents related to telephony, which may mean either the uselessness of such industry standards or the lack of established practice.

The first option - the absence of the need for standards, or rather the currently undeveloped standard - can be acceptable for two reasons.

- Historically, the main VoIP protocols are SIP and H.323. SIP standards are certainly needed, but for a long time SIP did not claim to be the leading standard. It was assigned H.323 (H.323 is the first VoIP protocol stack, which was adopted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in 1996). SIP by this time was only gaining popularity, and only in 1999 was the IETF described in RFC2543 recommendations. In subsequent years, both protocols developed in parallel precisely because there was no approved SIP standard and, consequently, excessive formalism when making additions / changes, the SIP protocol evolved more rapidly in a dynamically developing telecommunications market.

Also, do not forget that H.323 appeared earlier, and many manufacturers and service providers have already invested heavily in H.323 equipment and were not interested in developing SIP standards. This situation with H.323 is one of the main reasons why there is still no SIP standard. - Internet telephony protocols are somehow tied to integration with conventional telephony, which, by virtue of historical development and hardware, is inferior to modern means of communication. For example, you can never make a video call with a regular phone - this is obvious. Consequently, the developers have redistributed their forces to other, more promising areas - unified communications, video conferencing, instant messengers, etc.

We list the main "telephone" RFC:

- SIP (Session Initiation Protocol) is a protocol for establishing connections (session). It has many RFCs, the first of which appeared RFC2543 back in 1999. Then, in 2002, the protocol was somewhat revised and RFC3261 was released , which is considered the Standards Track to date. In fact, SIP is analogous to SS-7 “for the IP world”, the purpose of the protocol is to find the subscriber, establish its status and organize a communication session with it. The actual transmission of voice information is carried out via RTP or H.323.

- RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol) is a real-time transmission protocol. The protocol description first appeared in RFC1889 back in 1996, and in 2003 it was replaced with RFC3550 . The protocol describes ways of transmitting multimedia data (not just voices) in real time. And this is the only protocol associated with telephony, which has the highest status of Internet Standard.

- RTSP (Real Time Streaming Protocol) is a real-time streaming protocol. Describes RFC2326 . If RTP was responsible for restoring the end-to-end data transfer session and format description, then RTSP is a protocol that describes streaming multimedia information and accessing data streams, which greatly expands RTP functionality, for example, by implementing conferencing or recording streaming information to servers .

- RTCP (Real-Time Transport Control Protocol) is a real-time transmission control protocol. Complements RTP with monitoring and quality control functions. It has the same RFC number as the RTP, RFC3550 . Actually, RTCP was the reason for replacing the old RFC1889.

- ENUM is an acronym for E.164 NUmber Mapping. Historically described by the standard RFC2915 (dedicated to the Name Authority Pointer (NAPTR) - one of the types of resource records in the domain name system (DNS)), but with later additions RFC3761 , RFC6116 and RFC6117 . This standard is perhaps worth describing in more detail in other articles, but if it is short, ENUM is a set of protocols for combining Internet telephony and PSTN at the level of subscriber selection using the usual telephone number. ENUM is something similar to DNS, but for telephone numbers, and is intended to expand telephone numbering plans with online customers.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/321138/

All Articles