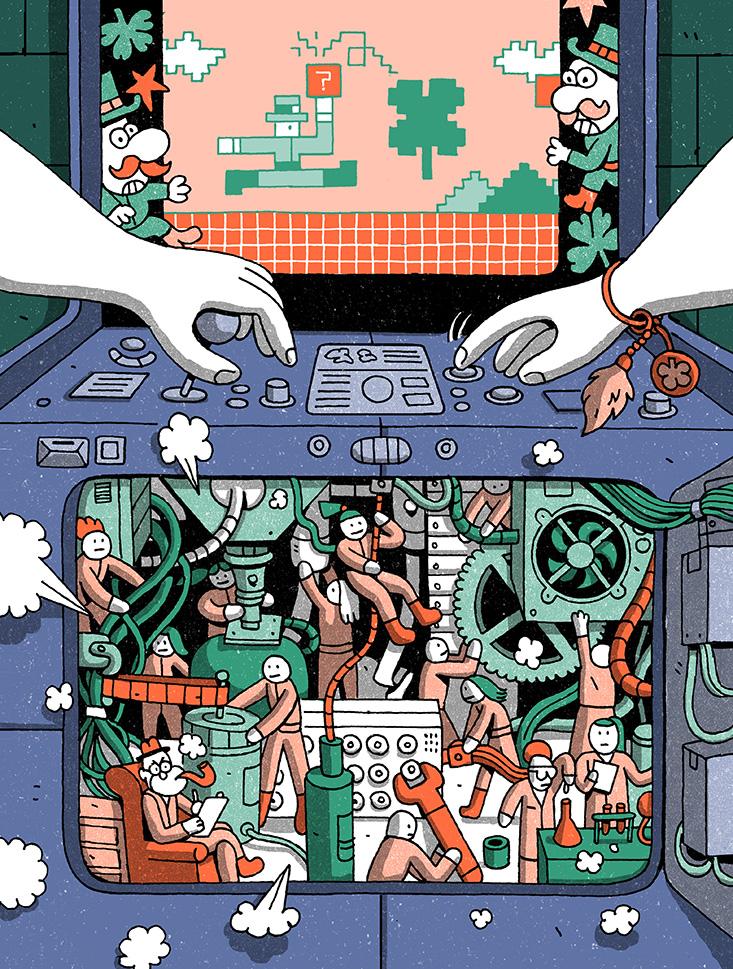

How designers manage luck in games

On September 16, 2007, the Japanese youtouber under the nickname Computing Aesthetic uploaded a 48-second video with the loud title “ULTRA MEGA SUPER LUCKY SHOT” (“ULTRAMEGASUPERAGNED SHOT”). The video shows an over-performance shot in the popular game Peggle, partly based on the principle of Japanese pachinko machines. In this game, the ball flies around the screen, earning points when hitting the multicolored pins, which disappear almost immediately after the impact; the more beats, the more points. Although skill is required in Peggle - before a shot the player must accurately aim - in principle, the game depends on the success of the ball bounces. In the Computing Aesthetic video, a player earns a huge amount of points due to successful bounces between pins. To emphasize the seemingly successful shot, the game until the last frame of the video loses Beethoven's euphoric “Ode to Joy”, after which the ball falls into the hole at the bottom of the playing field and the flickering “FEVER SCORE” appears on the screen. In the description for the video, which was scanned almost a quarter of a million times, it says “I couldn't balieve this when it happened !!!!!!!!!” (“I can’t believe it happened !!!”

Sharper BC. In the burials were found con game bones, often made from the hooves of animals. Such finds prove that even if the ancients believed that the roll of bones expressed the divine will, they were not averse to extending a helping hand to the gods. Photo: Vassil / Creative Commons.

Computing Aesthetic video is one of about 20,000 of the same clips on YouTube marked “Peggle” and “Lucky.” The clips were uploaded by players so overwhelmed with success in the game that they could not but share their achievements with the world. But these players may not be as lucky as they think. “The seemingly random bounces of the pins in Peggle were sometimes controlled by the game in order to provide the player with good results,” one of the game's developers, Jason Kapalka, confessed to me. “Occasionally a“ successful rebound ”was used, which guarantees that the ball would hit the pin instead of a dip in the“ dead ”zone. But we also added “good luck” players in the half-dozen first levels so that they are not so irritated by the learning curve. ” According to Kapalka, a small correction of the direction of a rebound by a few degrees (but not so much that the ball's behavior in the air looked artificial) is enough to motivate the beginners, and not to make the game too unrealistic.

Most video games imply honesty. Guided by an all-knowing and all-powerful designer, the game should be as fair as possible, and players expect it. (Designers have an incentive not to cheat: a game that always wins will soon stop playing.) However, when video games do play by the rules, players may feel deceived. Sid Meier, the designer of the computerization game Civilization, in which players lead their people through centuries of history, politics and wars, quickly learned to change the odds inside the game to compensate for this psychological problem. Thorough testing of the game showed that when a player who was predicted to have a 33 percent chance of winning the battle lost three times in a row, he felt anger and distrust. (In Civilization, you can replay the same battle to win, suffering losses at each loss.) Therefore, Meyer changed the game so that it better corresponded to the cognitive distortions of the person. If the odds of winning the battle are one to three, then the game ensures that you win on the third attempt. This is a violation of the true principle of probability, which, however, introduced the illusion of honesty. Let's call it the “paradox of luck”: luck is great, but too much luck is unrealistic. The final unspoken agreement between players and designers can be considered the most abstract of the "public contracts".

')

In ancient times, luck was usually attributed to divine intervention: games were both fun for the gods, and testing of human qualities. Luck is the central component of the games of the ancient Egyptians; according to Plato, the Egyptian god Toth invented the dice. In practice, bones were usually made from the ram bones of hoofed animals, they were polished and used in Egyptian board games and bone divination. In the tombs, along with the ancient game boards found scam "charged" bones. Even if the ancient Egyptians believed that throwing a dice somehow expresses the divine will, they were not against it.

The 11th-century Norwegian king Olaf Haraldsson, once put a kingdom on the game on the bones. Olaf had territorial differences with the Swedish king over Hising Island. In the end, both agreed to resolve the issue by throwing the bones. The Swedish king threw two sixes, the maximum number of points, and said that there is no point in continuing the game. Olaf insisted on his throw: having recently adopted Christianity, he was sure that God would turn the bones in his favor. His faith was rewarded with two sixes. They continued to throw the dice, each time throwing twelve points. The thing ended up was that during the last throw of Olaf, one of the bones broke into two parts, showing a six and a unit. Happy thirteen points helped him win the kingdom.

Luck is just as important in modern games, from shaking bones in a glass to the treacherous Chance cards in Monopoly. But its role has changed: Man took power from the gods, and luck has become a design tool that can change the gameplay and expectations of the player. For example, it allows players with different skill levels to play together, reducing the benefits given by skills. Designer Zach Gage (Zach Gage) from New York recently decided to reinvent chess, adding a significant element of luck to it. “Chess has always been a very balanced game, completely dependent on the skill of the player,” he says. “It's great if you want to find out who plays better, but it’s not suitable if you want to play an interesting game with friends who have different levels.”

Really Bad Chess, on the contrary, at the beginning of each game gives each player a randomly selected set of pieces. The sides do not mirror each other, so one player may end up with five queens, and another - a whole battalion of pawns. “This solves two problems,” says Gage. “Weak players can feel that they have a chance to beat the strong thanks to good pieces. And it becomes more difficult to evaluate the forces of opponents, even for a specialist. ” Here, as in poker, the victory is determined by both the luck of the hand and the player’s talent. This design also allows Gage to secretly control the probability of initial distribution. For example, you can increase the likelihood of distribution to a newcomer more powerful figures, and put an experienced player at a disadvantage.

In mechanical games, luck is the only salvation of the player from the mechanism itself. In the early 1950s, the Chicago-based pinball automaker Gottlieb noticed that beginning pinball players sometimes miss the ball in the very first seconds of the game. Therefore, he added an inverted V-shaped metal wall, which in the first seconds of the game rose above the flippers at the bottom of the machine so that the ball would not fall down. In more modern pinball machines, the blocking gates known as “ball saver” (the name coined by Chicago Coin for its 1968 Gun Smoke machine gun) are programmatically controlled. Lifting the wall depends on luck, which is implemented in the algorithm.

Intentional blunder: slot machines often use the illusion of luck. Everything looks as if the player almost hit a big jackpot, for example, the last bar of gold or a lemon scrolls down and stops nearby, almost reaching the jackpot.

In fully digital video games, luck is even more woven into the gameplay and must be actively simulated. When a soccer ball flies past the goalkeeper or a string of racing cars inexplicably slows down so that the player can catch up with it, the hand of the game designer invisibly interferes with the process. The purpose of such manipulation is to encourage the player and thus maintain his interest. But this trick needs to be used gracefully. The player who feels the secret help of the game will feel that he is being taken care of. In the end, luck happens only when it is truly unpredictable.

And here the problems begin.

When the gods ruled success, we could only pray to them for good fate. Now the architects of our destiny in games can be found on LinkedIn. Because of this knowledge, our sensitivity to chances, which we consider unfair, has increased, and designers need to compensate for it.

“As soon as a player learns about any pseudo-randomness of a game, he risks losing the feeling of luck,” says designer Paul Sottosanti from Riot Games, publisher of League of Legends (one of the most popular online games). Games in which players are given seemingly random rewards often use a mechanism known as the “pity timer”. He guarantees that the player will experience seemingly random luck through an average interval of failures (from about 10 minutes to an hour, depending on the game). In World of Warcraft, each time an enemy is killed, players hope to get a legendary (especially powerful) game weapon. The legendary weapon has an infinitely small chance of falling, but it also depends on the “compassion timer”. “When a player just waits for the timer to work, he may become tired,” says Sottosanti. "The first feeling that a player feels when he finally finds a" legend "is often not joy, but relief, perhaps tinged with sadness."

Some examples of pseudo-randomness are designed to provide a sense of honesty, while others are designed for profit. With the heyday of the so-called freemium games - free games, earning real games on the sale of virtual items - there is a temptation to manipulate what looks like a chance coincidence to stimulate further spending. Sottosanti cites the popular virtual card game Hearthstone as a good example of “timers of compassion”. “The chance of getting a valuable card increases with each set that it does not contain. The player is actually guaranteed to receive a valuable card after the opening of 40 sets. ” Kits are sold to players for money.

This technique is taken straight from the book of the American psychologist B. Skinner (BF Skinner). Skinner found that no matter who participates in experience: a pigeon, a rat, or a human, the most effective way to reinforce learned behavior is to reward on a random schedule. The developers of free games have figured out that by occasionally giving out small awards can sustain the interest (and purchases) of players longer.

Natasha Schüll is an assistant professor of media, culture and communications at New York University, and the author of Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (“Getting used to the goal: Las Vegas gaming machines”). According to her, when a player feels that he is favored by luck, “this can be attributed to the injection of certain neurotransmitters and the release of dopamine. Even an obsessive search and desire to restore this feeling of euphoria is controlled by the pleasure center in the brain. ” The ability of dopamine to turn us into hunters for good luck can most clearly be seen in the effects of certain drugs used to cure Parkinson's syndrome. It is noticed that flooding the brain with dopamine, they turn patients into ludomanov.

The temptation to manipulate probabilities to form the attachment of the human brain is greatest in the gambling industry. Whether the game is conducted on the Internet or on a slot machine in a casino, the program usually manages the calculations. The results of the game of any modern slot machines are based on secret random number generators in computer networks, and not from the happy coincidence of pictures on three wooden cylinders. But losing with such a system of “luck” can be dismal. Therefore, in the gaming machines often used the illusion of physical luck. Everything looks as if the player almost hit a big jackpot, for example, the last bar of gold or a lemon scrolls down and stops nearby, almost reaching the jackpot. This lures the players to continue betting on the odds remaining scanty.

“Close blunders give rise to mixed feelings,” explains psychologist and director of the Center for the Study of Gambling at the University of British Columbia, Luke Clark (Luke Clark). “On the one hand, close misses cause disgust, but at the same time increase motivation. On slot machines, a close slip increases the chance of continuing the game, because the player feels he is starting to play better. ”

For games that are highly dependent on luck, maintaining this illusion of improvement and control is critical. “The most important role in this case is played by the brain structure called the striatum, an accumulation of nuclei in the center of the brain, which regulates movement and reward.” This area of the brain makes a particularly strong contribution to the feeling that we have “grabbed our luck.” "The same area is involved in the formation of habits, which, obviously, is also associated with addiction."

By convincing the player that he is improving in a game based on luck, we, in turn, increase the likelihood that he will bet on winning odds. “Over the years of its existence, the gambling industry has been able to track the actions of individual players, create full-fledged profiles of average customers and use algorithms that predict the exit from the game,” says Schül. Operators of digital gaming machines have the opportunity on the basis of these profiles to change the chances of winning directly during the gaming session. Thus, they may tempt players to continue the game. In many countries there are laws prohibiting such manipulations of "luck." To circumvent them, casino operators established the position of so-called “ambassadors of fortune” (luck ambassadors). They visit the casino and give players cash bonuses to invest in the game. Freemium games that are not yet subject to such legal restrictions are free to give players bonuses so that they feel lucky and continue to play, spending their money.

Some designers have completely abandoned the use of "leverage of luck." For a long time, the famous pinball machine developer Larry DeMar (Larry DeMar), who worked with Williams, did not use the ball saver walls in the company's machines, believing that they destroy the purity of the game. If you lose - you lose, no luck.

Unfortunately, this approach does not always attract players. “Today, players almost always see patterns of manipulation where there are none,” says Peggle developer Jason Kapalka. “When I was working on online games, it was almost impossible to convince some players that the results were somehow not rigged. People built detailed theories about how new players get better results in order to tie them to a paid subscription, or that old players are rewarded for their consistency, and so on. ” At some point, Kapalka published voluminous files with hundreds of thousands of simulated rolls of bones to convince skeptical players of the true randomness of the results.

Samih game designers can also be confused. “Even an experienced designer can get confused in a fairly large project,” an experienced designer Adam Saltsman told me. "And even an experienced player can misunderstand the system, taking the skill for luck, or vice versa."

If a game for a person is a way of preparing for life, then it is logical that we need to add to our games of uncertainty, moments of impermanence, to which we will have to adapt our attitude and strategies. But we have become more demanding on how luck should serve us in games - not too much, but not too little. Unchanged remains our interest in the nature of the success we experience. “When we meet in the game with luck, we feel a deep sense of alignment and coherence, almost the same as if we found a pattern and were able to predict it,” says Schül.

The source of this luck - whether it be gods or a random probability distribution - is a property of culture. But the promise of meeting with luck in the game comforts everyone: we found what we were looking for.

About the author: Simon Parkin (Simon Parkin) - author of the book Death by Video Game: Danger, Pleasure, and Obsession on the Virtual Frontline (“Death from a video game: danger, pleasure and obsession on the virtual front”), essays and articles in various publications including newyorker.com, The Guardian, The New York Times, MIT Technology Review and New Statesman.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/320296/

All Articles