What is enterprise architecture, and why was Zachman wrong?

The second article about the mythological consciousness will also be short. Today I will tell you how the mythological consciousness causes problems when modeling an enterprise architecture.

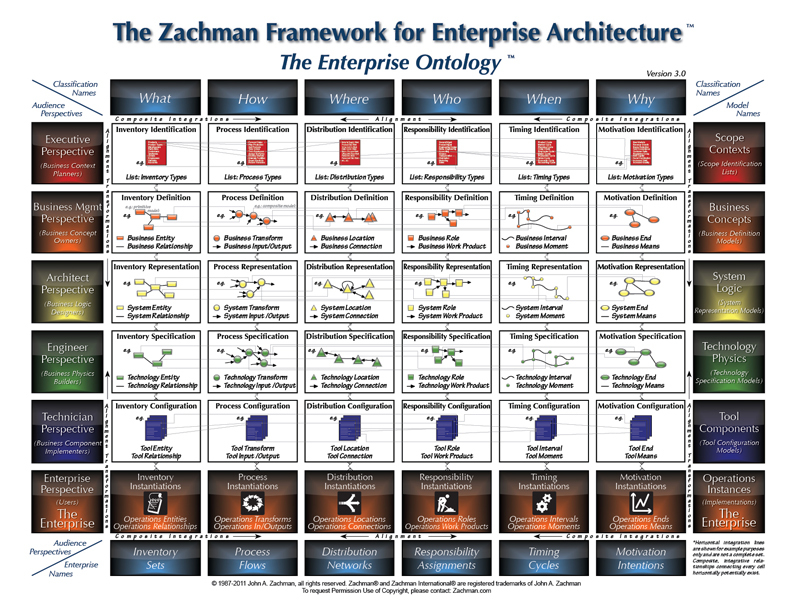

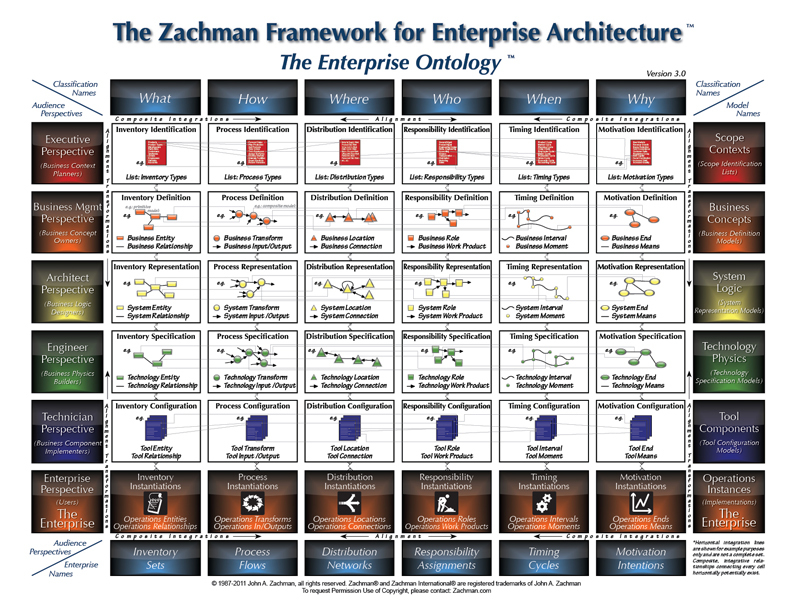

The well-known Zachman model tries to answer the question of what an enterprise architecture is, and talks about how it should be modeled. The basis of this model are the questions that are asked to answer: who, when, where, why and how does something on something. It seems that this is a logical framework for describing the enterprise architecture, and many people think that this is the way it is.

However, even a quick glance at this framework leaves a feeling of dissatisfaction, because it is not clear how to answer the question: who and why carved the part? Who: Ivan Ivanovich, or turner, whose role was played by Ivan Ivanovich? Why: because the turner received the task, or because Ivan Ivanovich signed a contract, in accordance with which he undertakes to fulfill the role of turner in exchange for food? Why: because Ivan Ivanovich wants to eat, or because the part is needed in the assembly shop?

')

A deeper study of this framework makes you think about its applicability to the description of technological processes. For example, let the corn grow in the field. Applying the Zachman model, I have to answer the questions. Who! Corn. What is he doing? It grows. Why? Because this is how the world works. What for? But who knows why growing corn?

A reader trained in the description of enterprise architectures will quickly correct me. He will say that I incorrectly raise questions. We must ask: who grows, why he grows, what grows. But then it turns out that I can describe the activities of the subject who grows corn, but I cannot describe the growth itself. Having resigned myself to the fact that I cannot describe the growth process, I still have unresolved questions: who and why grows corn (see above)?

It turns out that by asking seemingly logical questions, I get several answers at best, and at worst, I don’t get them at all. If we take the extreme case, when we have a fully robotized enterprise, in which there are no people at all, then the answer to the question "who?" Will be - "no one". As a result, we cannot say anything about this enterprise at all! True, there is one way out of this situation, a little crafty, - you just need to use the mythical consciousness and animate robots. Then, animate the inanimate, we can answer the question: who? Robot. Why? Because this is how the robot works, or because the programmer has programmed it that way. On the second question, we again get strange answers. Why did this happen, and what questions are really worth asking? I will try to briefly express my opinion on this matter, talking about the logical errors that I found in the Zachman model.

If you look at the questions that are asked in the Zachman model, you can see that they correspond exactly to the theory of activity. Activity is the mental function of the subject (group of subjects). Therefore, answering the questions of Zakhman, we build a model of the mental function of the subject (s). The science that studies the mental functions of subjects is called psychology. It turns out that Zachman answers the questions that psychologists ask: why does the subject do this or that action? Or how to motivate the subject to perform certain actions? These questions are certainly interesting and important, but are the answers to them a description of the enterprise architecture? To answer this question, you need to understand what is an enterprise?

How does the enterprise design actually occur and what artifacts arise at the same time? Before designing an enterprise, a model of requirements for it is built. The requirements model is based on the requirements that are submitted to this enterprise from all its participants, counterparties and stakeholders. Analogue in IT - requirements for software. Further, on the basis of these requirements, a model of enterprise processes is built with the necessary level of detail. An analogue in IT is the list of functions of a software product. Next, a model of functional objects is built, or, in a specialized language, technical places that should participate in the processes listed earlier. Analog to IT will be a description of the procedures, and an explanation of which procedures are involved in which functions. Next, select those units of equipment that can perform the role of the listed technical locations. Analog in IT is a software code.

An enterprise is a functional entity that is created to satisfy certain requirements. In this sense, an enterprise is no different from an object such as a watch, or a production line. Often, instead of the term functional entity, you can hear the term technical place. A technical place is different from a piece of equipment in that the piece of equipment serves as a technical place. For example, a transformer plays the role of a voltage converter, while at different times different transformers can play the role of the same converter. Another example of a technical place is the position, department, division, staff. For example, the turner is involved in the function of manufacturing parts. This is a technical place, the role of which at different times can be performed by different pieces of equipment (individuals). I briefly wrote about the difficulties of modeling technical sites and equipment in the article Modeling Enterprise Assets: Modern Standards and Practice .

When modeling technical locations, we describe the processes and participants in these processes. I note that it is the participants, not the performers, that the transformer cannot convert voltage, because it is not an animate being. I wrote about this in the last article Modeling Activity and Mythological Consciousness . If, nevertheless, to say that a transformer "converts" voltage, then this is a metonymy, which is revealed as follows: a transformer plays the role of a voltage converter, which (converter) participates in the process of voltage conversion. You can read about metonymy in the book Metaphors We Live By, authors: George Lakoff, Mark Johnson. Another common metonymy would be: “a computer solves problems.” Those who truly believe that a transformer, or a computer, actually does something, animate the inanimate using the mythical consciousness.

Note that until now we have not said a word about the goals, the executors and the cause-effect relationships. We only talked about the requirements, the functions and participants of these functions - technical places. The goals remained at the stage of formation of requirements for the enterprise and then they did not go. We may know these goals, but we may not know - for the enterprise model this does not matter. The enterprise model answers the question: how do we satisfy the requirements, and not where these requirements come from. There are no performers either, because we do not need to use the theory of activity to describe the activity participants. We do not build causal relationships. If it is necessary to build a model of cause-effect relationships, then this is another additional model. This is the knowledge that technologists use when designing an enterprise, and I did not see anyone build such models. This is industry knowledge, and they have been taught in institutions for many years. To simulate why an airplane is flying is unrealistically difficult, and no one does. Just simulate the flight of the aircraft.

So, the Zachman model does not include requirements for an enterprise, includes a model of processes, but in a rather specific way - indicating the executors of the process, which, as I said, can only be found in the theory of activity, and do not separate the model of technical places and the model units of equipment.

As I said earlier, the Zachman model is more like an activity. In this case, it would be nice if the Zachman model was used for its intended purpose, as a way of describing activities. This would give an opportunity to analyze the motives and interest of people in their work, but the trouble is that this model is used incorrectly. For example, to the question “why does the turner sharpen the part?” One can get the answer: “it is needed in the assembly shop” But the need for it in the assembly shop does not answer the question why the turner sharpens the part. The answer was not to the question posed, but to some other one. For example, for such an answer the question would be correct: in which process, or in what operation should the machined part participate? Or in what workplace is it needed? You see that it is not at all the question “why?”. In addition, I am greatly confused by the fact that Zahman is given a computer or an information system with the ability to do something. Most likely, he does not animate them, but uses metonymy in modeling, which, in my opinion, is unacceptable.

The correct questions are: What are the requirements for the enterprise? What processes take place in the enterprise? What technical places are involved in what processes? What pieces of equipment perform the roles of what technical places and when?

Actually, everything. Happy New Year and see you soon!

The well-known Zachman model tries to answer the question of what an enterprise architecture is, and talks about how it should be modeled. The basis of this model are the questions that are asked to answer: who, when, where, why and how does something on something. It seems that this is a logical framework for describing the enterprise architecture, and many people think that this is the way it is.

However, even a quick glance at this framework leaves a feeling of dissatisfaction, because it is not clear how to answer the question: who and why carved the part? Who: Ivan Ivanovich, or turner, whose role was played by Ivan Ivanovich? Why: because the turner received the task, or because Ivan Ivanovich signed a contract, in accordance with which he undertakes to fulfill the role of turner in exchange for food? Why: because Ivan Ivanovich wants to eat, or because the part is needed in the assembly shop?

')

A deeper study of this framework makes you think about its applicability to the description of technological processes. For example, let the corn grow in the field. Applying the Zachman model, I have to answer the questions. Who! Corn. What is he doing? It grows. Why? Because this is how the world works. What for? But who knows why growing corn?

A reader trained in the description of enterprise architectures will quickly correct me. He will say that I incorrectly raise questions. We must ask: who grows, why he grows, what grows. But then it turns out that I can describe the activities of the subject who grows corn, but I cannot describe the growth itself. Having resigned myself to the fact that I cannot describe the growth process, I still have unresolved questions: who and why grows corn (see above)?

It turns out that by asking seemingly logical questions, I get several answers at best, and at worst, I don’t get them at all. If we take the extreme case, when we have a fully robotized enterprise, in which there are no people at all, then the answer to the question "who?" Will be - "no one". As a result, we cannot say anything about this enterprise at all! True, there is one way out of this situation, a little crafty, - you just need to use the mythical consciousness and animate robots. Then, animate the inanimate, we can answer the question: who? Robot. Why? Because this is how the robot works, or because the programmer has programmed it that way. On the second question, we again get strange answers. Why did this happen, and what questions are really worth asking? I will try to briefly express my opinion on this matter, talking about the logical errors that I found in the Zachman model.

If you look at the questions that are asked in the Zachman model, you can see that they correspond exactly to the theory of activity. Activity is the mental function of the subject (group of subjects). Therefore, answering the questions of Zakhman, we build a model of the mental function of the subject (s). The science that studies the mental functions of subjects is called psychology. It turns out that Zachman answers the questions that psychologists ask: why does the subject do this or that action? Or how to motivate the subject to perform certain actions? These questions are certainly interesting and important, but are the answers to them a description of the enterprise architecture? To answer this question, you need to understand what is an enterprise?

How does the enterprise design actually occur and what artifacts arise at the same time? Before designing an enterprise, a model of requirements for it is built. The requirements model is based on the requirements that are submitted to this enterprise from all its participants, counterparties and stakeholders. Analogue in IT - requirements for software. Further, on the basis of these requirements, a model of enterprise processes is built with the necessary level of detail. An analogue in IT is the list of functions of a software product. Next, a model of functional objects is built, or, in a specialized language, technical places that should participate in the processes listed earlier. Analog to IT will be a description of the procedures, and an explanation of which procedures are involved in which functions. Next, select those units of equipment that can perform the role of the listed technical locations. Analog in IT is a software code.

An enterprise is a functional entity that is created to satisfy certain requirements. In this sense, an enterprise is no different from an object such as a watch, or a production line. Often, instead of the term functional entity, you can hear the term technical place. A technical place is different from a piece of equipment in that the piece of equipment serves as a technical place. For example, a transformer plays the role of a voltage converter, while at different times different transformers can play the role of the same converter. Another example of a technical place is the position, department, division, staff. For example, the turner is involved in the function of manufacturing parts. This is a technical place, the role of which at different times can be performed by different pieces of equipment (individuals). I briefly wrote about the difficulties of modeling technical sites and equipment in the article Modeling Enterprise Assets: Modern Standards and Practice .

When modeling technical locations, we describe the processes and participants in these processes. I note that it is the participants, not the performers, that the transformer cannot convert voltage, because it is not an animate being. I wrote about this in the last article Modeling Activity and Mythological Consciousness . If, nevertheless, to say that a transformer "converts" voltage, then this is a metonymy, which is revealed as follows: a transformer plays the role of a voltage converter, which (converter) participates in the process of voltage conversion. You can read about metonymy in the book Metaphors We Live By, authors: George Lakoff, Mark Johnson. Another common metonymy would be: “a computer solves problems.” Those who truly believe that a transformer, or a computer, actually does something, animate the inanimate using the mythical consciousness.

Note that until now we have not said a word about the goals, the executors and the cause-effect relationships. We only talked about the requirements, the functions and participants of these functions - technical places. The goals remained at the stage of formation of requirements for the enterprise and then they did not go. We may know these goals, but we may not know - for the enterprise model this does not matter. The enterprise model answers the question: how do we satisfy the requirements, and not where these requirements come from. There are no performers either, because we do not need to use the theory of activity to describe the activity participants. We do not build causal relationships. If it is necessary to build a model of cause-effect relationships, then this is another additional model. This is the knowledge that technologists use when designing an enterprise, and I did not see anyone build such models. This is industry knowledge, and they have been taught in institutions for many years. To simulate why an airplane is flying is unrealistically difficult, and no one does. Just simulate the flight of the aircraft.

So, the Zachman model does not include requirements for an enterprise, includes a model of processes, but in a rather specific way - indicating the executors of the process, which, as I said, can only be found in the theory of activity, and do not separate the model of technical places and the model units of equipment.

As I said earlier, the Zachman model is more like an activity. In this case, it would be nice if the Zachman model was used for its intended purpose, as a way of describing activities. This would give an opportunity to analyze the motives and interest of people in their work, but the trouble is that this model is used incorrectly. For example, to the question “why does the turner sharpen the part?” One can get the answer: “it is needed in the assembly shop” But the need for it in the assembly shop does not answer the question why the turner sharpens the part. The answer was not to the question posed, but to some other one. For example, for such an answer the question would be correct: in which process, or in what operation should the machined part participate? Or in what workplace is it needed? You see that it is not at all the question “why?”. In addition, I am greatly confused by the fact that Zahman is given a computer or an information system with the ability to do something. Most likely, he does not animate them, but uses metonymy in modeling, which, in my opinion, is unacceptable.

The correct questions are: What are the requirements for the enterprise? What processes take place in the enterprise? What technical places are involved in what processes? What pieces of equipment perform the roles of what technical places and when?

Actually, everything. Happy New Year and see you soon!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/318232/

All Articles