How Yandex taught the machine to create translations for rare languages

In Russia alone, there are more than a hundred languages, many of which are native to tens and hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover, some of them are limited in use or even on the verge of extinction. Machine translation could help preserve these languages, but for this it is necessary to solve the main problem of all such systems - the lack of examples for learning.

Yandex has been working on machine translation technology since 2011, and today I will talk about our new approach, thanks to which it becomes possible to create a translator for those languages for which it was previously difficult to do.

')

Rules against statistics

Machine translation, that is, automatic translation from one human language to another, originated in the middle of the last century. The starting point is considered to be the Georgetown experiment, conducted on January 7, 1954, in which more than 60 phrases in Russian were translated by computer into English. In fact, it was not an experiment at all, but a well-planned demonstration: the dictionary included no more than 250 entries and worked taking into account only 6 rules. Nevertheless, the results impressed the public and spurred the development of machine translation.

Such systems were based on dictionaries and rules that determined the quality of translation. Over the years, professional linguists have worked to derive more and more detailed and comprehensive manual rules (in fact, regular expressions). This work was so laborious that serious attention was paid only to the most popular pairs of languages, but even within the framework of these machines the machines coped poorly. Living language is a very complex system, which is poorly governed by the rules, constantly evolving and almost every day is enriched with new words or constructions. It is even more difficult to describe the rules for the correspondence of two languages. The same words can have completely different translations depending on the context. Yes, and whole phrases can have their own stable translation, which is better suited. For example, " It is not so easy to enter Mordor ."

The only way for a machine to constantly adapt to changing conditions and take context into account is to learn from a large number of relevant texts and independently identify patterns and rules. This is the statistical approach to machine translation. These ideas have been known since the middle of the 20th century, but they didn’t receive much widespread use: machine translation based on rules worked better in the absence of large computing power and training facilities.

Brute power of computers is not science

A new wave of development of the statistical approach began in the 80-90s of the last century. IBM Research has gained access to a large number of Canadian parliament documents and used them to work on a spelling checker system. And for this they applied a rather interesting approach, known as the noisy channel model. Its meaning is that text A is considered as text B, but with errors. And the task of the machine is to eliminate them. The model was trained on thousands of already typed documents. You can read more about noisy channel in other posts on Habré , but here it’s important to say that this approach showed itself well for spelling, and a group of IBM employees decided to try it for translation. Canada has two official languages (English and French), so with the help of a translator they hopedto fire half of the operators to reduce the amount of manually entered text. But over time there were problems, so they had to wait for the moment when the manager went on vacation, and the opportunity arose to be creative with deadlines and study.

The results of their work were published , but they did not impress everyone. The organizers of the COLING computer linguistics conference have written a devastating review:

The result was worse than the best systems based on rules at that time, but the approach itself, which involved reducing manual labor, interested researchers from all over the world. And the main problem that faced them was the lack of sufficient examples of translations for training the machine. Any materials that could be found were used: the databases of international UN documents, documentation, reference books, the Bible and the Koran (which were translated into almost all languages of the world). But more was needed for quality work.

Search

Every day, hundreds of thousands of new pages appear on the Internet, many of which are translated into other languages. This resource can be used to train the machine, but it is difficult to get it. Organizations that index the Internet and collect data on billions of web pages have this experience. Among them, for example, search engines.

Yandex has been working on its own machine translation system for five years, which is trained on data from the Internet. Its results are used in Translator, Search, Browser, Mail, Zen and many other services. She studies as follows. Initially, the system finds parallel texts at the addresses of documents - most often such addresses differ only in parameters, for example, “en” for the English version and “ru” for the Russian version. For each text studied, the system builds a list of unique features. These can be rarely used words, numbers, special characters that are in a text in a certain sequence. When the system is typing a sufficient number of texts with signs, it begins to look for parallel texts also with their help - comparing the signs of new texts and those already studied.

In order for the translator to meet modern quality standards, the system must learn millions of phrases in both languages. Search technologies can find them, but only for the most popular translation directions. For everyone else, you can try to study in the old manner only on Wikipedia or the Bible, but the quality of the translation is rolled back decades ago. You can connect crowdsourcing ( Yandex.Toloka or Amazon Mechanical Turk) and with the efforts of a large number of people from different countries to collect examples of translations. But it is long, expensive and not always effective. Although we try to use crowdsourcing where possible, we have managed to find an alternative solution.

Language as a set of models

For a long time, the basis of the statistical translation was exclusively lexical models, i.e. such models, which do not take into account the kinship between different words and other linguistic characteristics. Simply put, the words "mom" and "mom" are two completely different words from the point of view of the model, and the quality of the translation was determined only by the presence of a suitable example.

A few years ago, an understanding emerged in the industry that the quality of statistical machine translation can be improved by supplementing a purely lexical model with models of morphology (inflection and word formation) and syntax (construction of sentences). It may seem that this is a step back towards the manual rules of linguists, but this is not so. Unlike systems based on manual rules, patterns of morphology and syntax can be generated automatically based on the same statistics. A simple example with the word "mom". If we feed the neural network thousands of texts containing this word in various forms, the network will “understand” the principles of word formation and learn how to predict the correct form depending on the context.

The transition from a simple to an integrated language model was well reflected in the overall quality, but its work still requires millions of examples that are difficult to find for small languages. But it was here that we remembered that many languages are interconnected. And this fact can be used.

Family ties

We began by moving away from the traditional perception of each language as an independent system and began to take into account the family ties between them. In practice, this means this. If we have a language for which we need to build a translation, but there is not enough data for this, then we can take other, more “larger”, but related languages. Their separate models (morphology, syntax, vocabulary) can be used to fill voids in models of a “small” language.

It may seem that this is a blind copying of words and rules between languages, but the technology works somewhat smarter. I propose to consider it immediately on the real example of one very popular language in extremely narrow circles.

Papiamento

Papiamento is the native language of the population of Aruba , Curaçao and Bonaire, spoken by about 300 thousand people. Including one of our colleagues, who was born in Aruba. He suggested that we be the first to support Papiamento. We knew about these islands only on Wikipedia, but such an offer could not be missed. And that's why.

When people have to speak a language that is not native to any of them, new languages, called pidzhins, appear. Most often pidzhin arose on the islands that were seized by the Europeans. The colonialists brought labor from other territories there, and these people, who did not know each other’s languages, had to somehow communicate. Their only common language was the language of the colonialists, usually assimilated in a very simplified form. So many pidzhinov based on English, French, Spanish and other languages. Then people passed on this language to their children, and for those he became native. Pidgin, which became for someone native, are called Creole languages.

Papiamento - Creole, which appeared, apparently, in the XVI century. Most of his vocabulary is of Spanish or Portuguese origin, but there are words from English, Dutch, Italian, and also from local languages. And since previously we had not experienced our technology in Creole, we jumped at the chance.

Modeling any new language always begins with the construction of its core. No matter how “small” a language is, it always has unique features that distinguish it from any other. Otherwise, it simply could not be attributed to an independent language. These can be their own unique words or some word-formation rules that are not repeated in related languages. These features make up the core, which in any case must be modeled. And for this, a small number of translation examples is enough. In the case of Papiamento, at our disposal was the translation of the Bible into English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and, in fact, Papiamento. Plus a small amount of documents from the network with their translation into one of the European languages.

The initial stage of working on Papiamento was no different from creating a translator for any major language. We load into the machine all materials available to us and run the process. It passes through parallel texts written in different languages and builds the distribution of the translation probabilities for each word found. By the way, now it is fashionable to talk about the use of neural networks in this process, and we also know how to do it, but often simpler tools are enough. For example, for the Elvish language (we will talk about it a little later), we initially built a model using a neural network, but eventually we started without it. Because a simpler statistical tool showed the result not worse, but it took less effort. But we digress.

The system, looking at parallel texts, replenishes its vocabulary and memorizes translations. For large languages, where there are millions of examples, nothing more needs to be done - the system will find not only all words are possible, their forms will remember their translations, but also take into account the different cases of their use depending on the context. With a little tongue harder. We modeled the core, but examples are not enough to fully cover all words, word formation accounting. Therefore, the technology that underlies our approach works somewhat deeper with existing examples and uses knowledge of other languages.

For example, according to the morphology of the Spanish language, the plural is formed using the endings -s / -es. The machine, meeting with the plural in the Spanish translation, concludes for itself that the same word in translation to Papiamento is most likely written in the plural. Due to this feature, the automatic translator has deduced for itself the rule that words in papiamento with the ending -nan denote the plural, and if its translation is not found, then it is worth discarding the ending and try to find the translation for the singular. Similarly for many other inflection rules.

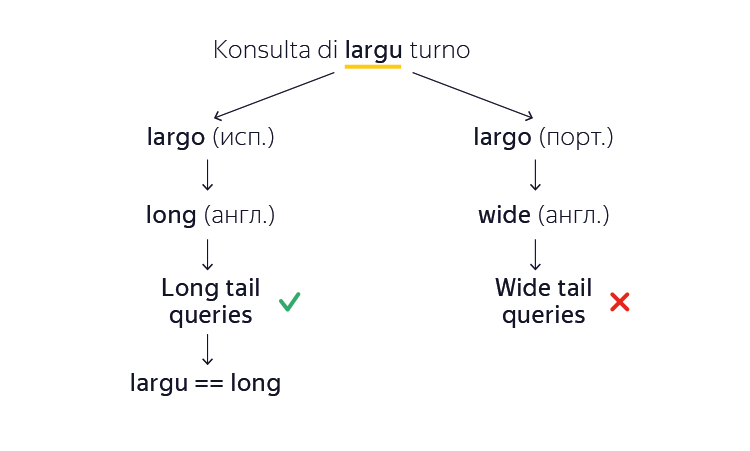

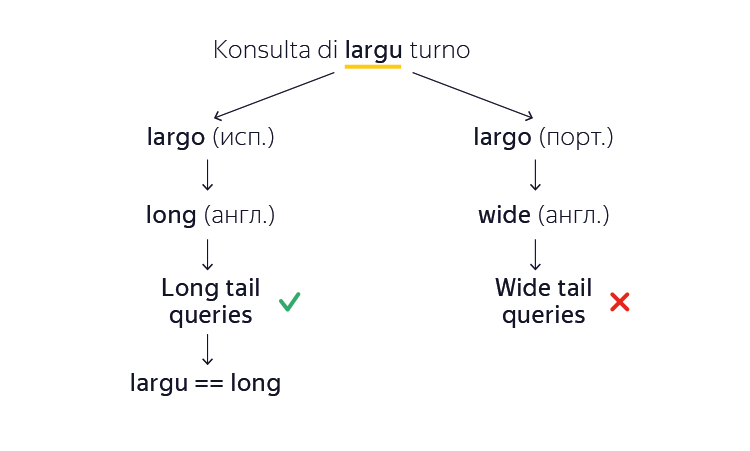

The morphology has become clearer, but what if even the initial form of the word machine is not yet known? We remember that the majority of all Papiamento words came from European analogues. Suppose that our automatic translator encounters the unknown word “largu” in papiamento and wants to find an English translation. The car notices that this word is very similar to the word “largo” from both Spanish and Portuguese. Here are just the meanings of these words do not match ("long" and "wide", respectively). And what language to navigate? The machine translation system solves this problem as follows. She builds both versions of the translation, and then, based on the millions of studied English documents, she concludes which of the options is more like a natural text. For example, “long tail queries” (long tail queries) is more like the truth than “wide tail queries” (wide tail queries). So she remembers that in this particular case the word “largu” came from Spanish, not from Portuguese. And so for most unknown words - the machine will automatically learn them without ready-made examples and manual intervention.

As a result, thanks to borrowing from larger languages, we were able to build a translation from / to Papiamento in such a volume of examples in which classical statistical machine translation simply could not cope.

Gornomarisky

Another example. We regularly add support for the languages of the peoples of Russia and at some point reached the Mari language, in which, from the very beginning of writing (in the 19th century), there were two literary options: meadow (eastern) and mountain (western). They differ lexically. However, languages are very similar and mutually understood. The first printed text in the Mari language, the Gospel of 1821, was High Mari. However, due to the fact that there are much more Mari meadows, the Mari language “by default” is usually considered meadow. For the same reason, there are much more texts in the Mari meadow, and we have no problems with the classical approach. But for mining, we applied our technology with borrowing. We took the ready-made meadow variant as a basis, and corrected the vocabulary using existing dictionaries. Moreover, the Russian language was also useful, which for many years had a considerable influence on the Mari language.

Yiddish

Yiddish arose in the X-XIV centuries on the basis of High German dialects - the same ones that formed the basis of the modern German language. Therefore, many Yiddish and German words are the same or very similar. This allowed us to use auxiliary models of vocabulary and morphology, collected according to the data for the German language. At the same time, writing in Yiddish is based on the Hebrew alphabet, therefore Hebrew was used to model it. According to our estimates, translation from / into Yiddish, supplemented with borrowings from Hebrew and German, is distinguished by higher quality in comparison with the classical approach.

Elven

Our team loves the works of the writer Tolkien; therefore, the translation of Sindarin (one of the languages of the elves of Middle-earth) was only a matter of time. As you understand, the language is rare, and its speakers are not so easy to meet. Therefore, we had to turn to linguistic studies of the writer. While writing Sindarin, the author was based on the Welsh language, and it contains characteristic alternations of initial consonants. For example, the "rune" will be "certh", and if there is a definite article in front of it, you get "i gerth". Many words were borrowed from the Irish, Scottish and Welsh. Fortunately, the author at one time compiled not only a detailed dictionary, but also rules for transliterating words from existing languages into Sindarin. All this turned out to be quite enough to create a translator.

Examples of languages where we used the new approach could be continued. By the current moment, we have managed to successfully apply the technology also in the Bashkir, Uzbek, Marathi and Nepali. Many of these languages can not even formally be called “small”, but the peculiarity of our approach lies precisely in the fact that it can be used everywhere where family ties are clearly visible. For small languages, he, in principle, allows you to create a translator, for others - to raise the bar of quality. And this is exactly what we plan to do in the near future.

Yandex has been working on machine translation technology since 2011, and today I will talk about our new approach, thanks to which it becomes possible to create a translator for those languages for which it was previously difficult to do.

')

Rules against statistics

Machine translation, that is, automatic translation from one human language to another, originated in the middle of the last century. The starting point is considered to be the Georgetown experiment, conducted on January 7, 1954, in which more than 60 phrases in Russian were translated by computer into English. In fact, it was not an experiment at all, but a well-planned demonstration: the dictionary included no more than 250 entries and worked taking into account only 6 rules. Nevertheless, the results impressed the public and spurred the development of machine translation.

Such systems were based on dictionaries and rules that determined the quality of translation. Over the years, professional linguists have worked to derive more and more detailed and comprehensive manual rules (in fact, regular expressions). This work was so laborious that serious attention was paid only to the most popular pairs of languages, but even within the framework of these machines the machines coped poorly. Living language is a very complex system, which is poorly governed by the rules, constantly evolving and almost every day is enriched with new words or constructions. It is even more difficult to describe the rules for the correspondence of two languages. The same words can have completely different translations depending on the context. Yes, and whole phrases can have their own stable translation, which is better suited. For example, " It is not so easy to enter Mordor ."

The only way for a machine to constantly adapt to changing conditions and take context into account is to learn from a large number of relevant texts and independently identify patterns and rules. This is the statistical approach to machine translation. These ideas have been known since the middle of the 20th century, but they didn’t receive much widespread use: machine translation based on rules worked better in the absence of large computing power and training facilities.

Brute power of computers is not science

A new wave of development of the statistical approach began in the 80-90s of the last century. IBM Research has gained access to a large number of Canadian parliament documents and used them to work on a spelling checker system. And for this they applied a rather interesting approach, known as the noisy channel model. Its meaning is that text A is considered as text B, but with errors. And the task of the machine is to eliminate them. The model was trained on thousands of already typed documents. You can read more about noisy channel in other posts on Habré , but here it’s important to say that this approach showed itself well for spelling, and a group of IBM employees decided to try it for translation. Canada has two official languages (English and French), so with the help of a translator they hoped

The results of their work were published , but they did not impress everyone. The organizers of the COLING computer linguistics conference have written a devastating review:

The result was worse than the best systems based on rules at that time, but the approach itself, which involved reducing manual labor, interested researchers from all over the world. And the main problem that faced them was the lack of sufficient examples of translations for training the machine. Any materials that could be found were used: the databases of international UN documents, documentation, reference books, the Bible and the Koran (which were translated into almost all languages of the world). But more was needed for quality work.

Search

Every day, hundreds of thousands of new pages appear on the Internet, many of which are translated into other languages. This resource can be used to train the machine, but it is difficult to get it. Organizations that index the Internet and collect data on billions of web pages have this experience. Among them, for example, search engines.

Yandex has been working on its own machine translation system for five years, which is trained on data from the Internet. Its results are used in Translator, Search, Browser, Mail, Zen and many other services. She studies as follows. Initially, the system finds parallel texts at the addresses of documents - most often such addresses differ only in parameters, for example, “en” for the English version and “ru” for the Russian version. For each text studied, the system builds a list of unique features. These can be rarely used words, numbers, special characters that are in a text in a certain sequence. When the system is typing a sufficient number of texts with signs, it begins to look for parallel texts also with their help - comparing the signs of new texts and those already studied.

In order for the translator to meet modern quality standards, the system must learn millions of phrases in both languages. Search technologies can find them, but only for the most popular translation directions. For everyone else, you can try to study in the old manner only on Wikipedia or the Bible, but the quality of the translation is rolled back decades ago. You can connect crowdsourcing ( Yandex.Toloka or Amazon Mechanical Turk) and with the efforts of a large number of people from different countries to collect examples of translations. But it is long, expensive and not always effective. Although we try to use crowdsourcing where possible, we have managed to find an alternative solution.

Language as a set of models

For a long time, the basis of the statistical translation was exclusively lexical models, i.e. such models, which do not take into account the kinship between different words and other linguistic characteristics. Simply put, the words "mom" and "mom" are two completely different words from the point of view of the model, and the quality of the translation was determined only by the presence of a suitable example.

A few years ago, an understanding emerged in the industry that the quality of statistical machine translation can be improved by supplementing a purely lexical model with models of morphology (inflection and word formation) and syntax (construction of sentences). It may seem that this is a step back towards the manual rules of linguists, but this is not so. Unlike systems based on manual rules, patterns of morphology and syntax can be generated automatically based on the same statistics. A simple example with the word "mom". If we feed the neural network thousands of texts containing this word in various forms, the network will “understand” the principles of word formation and learn how to predict the correct form depending on the context.

The transition from a simple to an integrated language model was well reflected in the overall quality, but its work still requires millions of examples that are difficult to find for small languages. But it was here that we remembered that many languages are interconnected. And this fact can be used.

Family ties

We began by moving away from the traditional perception of each language as an independent system and began to take into account the family ties between them. In practice, this means this. If we have a language for which we need to build a translation, but there is not enough data for this, then we can take other, more “larger”, but related languages. Their separate models (morphology, syntax, vocabulary) can be used to fill voids in models of a “small” language.

It may seem that this is a blind copying of words and rules between languages, but the technology works somewhat smarter. I propose to consider it immediately on the real example of one very popular language in extremely narrow circles.

Papiamento

Papiamento is the native language of the population of Aruba , Curaçao and Bonaire, spoken by about 300 thousand people. Including one of our colleagues, who was born in Aruba. He suggested that we be the first to support Papiamento. We knew about these islands only on Wikipedia, but such an offer could not be missed. And that's why.

When people have to speak a language that is not native to any of them, new languages, called pidzhins, appear. Most often pidzhin arose on the islands that were seized by the Europeans. The colonialists brought labor from other territories there, and these people, who did not know each other’s languages, had to somehow communicate. Their only common language was the language of the colonialists, usually assimilated in a very simplified form. So many pidzhinov based on English, French, Spanish and other languages. Then people passed on this language to their children, and for those he became native. Pidgin, which became for someone native, are called Creole languages.

Papiamento - Creole, which appeared, apparently, in the XVI century. Most of his vocabulary is of Spanish or Portuguese origin, but there are words from English, Dutch, Italian, and also from local languages. And since previously we had not experienced our technology in Creole, we jumped at the chance.

Modeling any new language always begins with the construction of its core. No matter how “small” a language is, it always has unique features that distinguish it from any other. Otherwise, it simply could not be attributed to an independent language. These can be their own unique words or some word-formation rules that are not repeated in related languages. These features make up the core, which in any case must be modeled. And for this, a small number of translation examples is enough. In the case of Papiamento, at our disposal was the translation of the Bible into English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and, in fact, Papiamento. Plus a small amount of documents from the network with their translation into one of the European languages.

The initial stage of working on Papiamento was no different from creating a translator for any major language. We load into the machine all materials available to us and run the process. It passes through parallel texts written in different languages and builds the distribution of the translation probabilities for each word found. By the way, now it is fashionable to talk about the use of neural networks in this process, and we also know how to do it, but often simpler tools are enough. For example, for the Elvish language (we will talk about it a little later), we initially built a model using a neural network, but eventually we started without it. Because a simpler statistical tool showed the result not worse, but it took less effort. But we digress.

The system, looking at parallel texts, replenishes its vocabulary and memorizes translations. For large languages, where there are millions of examples, nothing more needs to be done - the system will find not only all words are possible, their forms will remember their translations, but also take into account the different cases of their use depending on the context. With a little tongue harder. We modeled the core, but examples are not enough to fully cover all words, word formation accounting. Therefore, the technology that underlies our approach works somewhat deeper with existing examples and uses knowledge of other languages.

For example, according to the morphology of the Spanish language, the plural is formed using the endings -s / -es. The machine, meeting with the plural in the Spanish translation, concludes for itself that the same word in translation to Papiamento is most likely written in the plural. Due to this feature, the automatic translator has deduced for itself the rule that words in papiamento with the ending -nan denote the plural, and if its translation is not found, then it is worth discarding the ending and try to find the translation for the singular. Similarly for many other inflection rules.

The morphology has become clearer, but what if even the initial form of the word machine is not yet known? We remember that the majority of all Papiamento words came from European analogues. Suppose that our automatic translator encounters the unknown word “largu” in papiamento and wants to find an English translation. The car notices that this word is very similar to the word “largo” from both Spanish and Portuguese. Here are just the meanings of these words do not match ("long" and "wide", respectively). And what language to navigate? The machine translation system solves this problem as follows. She builds both versions of the translation, and then, based on the millions of studied English documents, she concludes which of the options is more like a natural text. For example, “long tail queries” (long tail queries) is more like the truth than “wide tail queries” (wide tail queries). So she remembers that in this particular case the word “largu” came from Spanish, not from Portuguese. And so for most unknown words - the machine will automatically learn them without ready-made examples and manual intervention.

As a result, thanks to borrowing from larger languages, we were able to build a translation from / to Papiamento in such a volume of examples in which classical statistical machine translation simply could not cope.

Gornomarisky

Another example. We regularly add support for the languages of the peoples of Russia and at some point reached the Mari language, in which, from the very beginning of writing (in the 19th century), there were two literary options: meadow (eastern) and mountain (western). They differ lexically. However, languages are very similar and mutually understood. The first printed text in the Mari language, the Gospel of 1821, was High Mari. However, due to the fact that there are much more Mari meadows, the Mari language “by default” is usually considered meadow. For the same reason, there are much more texts in the Mari meadow, and we have no problems with the classical approach. But for mining, we applied our technology with borrowing. We took the ready-made meadow variant as a basis, and corrected the vocabulary using existing dictionaries. Moreover, the Russian language was also useful, which for many years had a considerable influence on the Mari language.

Yiddish

Yiddish arose in the X-XIV centuries on the basis of High German dialects - the same ones that formed the basis of the modern German language. Therefore, many Yiddish and German words are the same or very similar. This allowed us to use auxiliary models of vocabulary and morphology, collected according to the data for the German language. At the same time, writing in Yiddish is based on the Hebrew alphabet, therefore Hebrew was used to model it. According to our estimates, translation from / into Yiddish, supplemented with borrowings from Hebrew and German, is distinguished by higher quality in comparison with the classical approach.

Elven

Our team loves the works of the writer Tolkien; therefore, the translation of Sindarin (one of the languages of the elves of Middle-earth) was only a matter of time. As you understand, the language is rare, and its speakers are not so easy to meet. Therefore, we had to turn to linguistic studies of the writer. While writing Sindarin, the author was based on the Welsh language, and it contains characteristic alternations of initial consonants. For example, the "rune" will be "certh", and if there is a definite article in front of it, you get "i gerth". Many words were borrowed from the Irish, Scottish and Welsh. Fortunately, the author at one time compiled not only a detailed dictionary, but also rules for transliterating words from existing languages into Sindarin. All this turned out to be quite enough to create a translator.

Examples of languages where we used the new approach could be continued. By the current moment, we have managed to successfully apply the technology also in the Bashkir, Uzbek, Marathi and Nepali. Many of these languages can not even formally be called “small”, but the peculiarity of our approach lies precisely in the fact that it can be used everywhere where family ties are clearly visible. For small languages, he, in principle, allows you to create a translator, for others - to raise the bar of quality. And this is exactly what we plan to do in the near future.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/317910/

All Articles