Assassin's Creed III mission design lessons in the open world

Assassin's Creed III was the game that prompted me to start a blog where I talked about the design of its various levels. This series of posts has become quite popular in the Assassin's Creed community. Although, to be honest, I recently tried to re-read them, and it would be better for me to leave them alone. What I wrote a few years ago now makes me feel ashamed (even if it seems from the outside that there are no reasons for it). On the other hand, this shame at least shows that over the years I have gained experience.

Now, I’ll come back to Assassin's Creed III in this article on the franchise and mission design in general. I think that this game is very suitable for studying the principles of open world level design, and not because it is perfectly implemented in the game. If you take the game as a whole, it is not. However, there are many positive and negative examples of missions in the open world. This means that their analysis will make useful conclusions, which I will share with you.

')

0. Breaking the rules is permissible if it makes sense.

Before I begin, I want to mention that we should not take each lesson as instruction. It is possible not to follow them, if it makes sense from the point of view of the player. Therefore, for each principle, I will try to find an example in which to ignore it.

1. Allow the player to reach the desired point in a convenient way.

If you want a player to get from point A to point B in an open world game, just put a point B marker and tell him to get there (this is exactly what creates a lot of possibilities of movement in the world). This may look obvious, especially considering that in previous games Assassin's Creed is often used. But in Assassin's Creed III, this is not always the case.

Take, for example, the mission “Battle of Bunker Hill” (Battle of Bunker Hill), the first task of which is to get to Putnam (Putnam). You not only have to be close to an occasional continental soldier who will lead you to the goal. He also refuses to move until you are on a horse. If you do not fulfill these two conditions and try to get to Putnam alone, the mission will fail and restart from the save point. This is incredibly limiting. If you need a player to follow a certain linear path, then create a classic linear environment. For example, as Tomb levels from previous games, or in the case of Assassin's Creed III, Treasure Map levels. For example, “Fort Wolcott” (Fort Wolcott) - is a linear level, while it is very interesting. But the open world and limited linear "paths" do not fit very well.

On the other hand, in the same mission, the Battle of Bunker Hill (Battle of Bunker Hill) is an example of when it makes sense not to allow the player to move along an arbitrary path. I'm talking about the accumulation of British forces and their lines of fire, which is between you and your victim. The British will kill you if you get too close. In my post, written a few years ago, I argued the opposite - that a player MUST be able to get through these troops. But, to be honest, basically I thought so because of the desire to see the event from the E3 trailer in the game itself.

I do not think that technically this is possible, because there are too many NPCs that affect the speed of the game. In Assassin's Creed: Unity with the technology of the new generation is permissible, but in Assassin's Creed III tricks and mirroring are used to display large crowds of people. From the point of view of logic, it is also obvious that a lonely fighter who fights with an entire army will die. Even if he is an almighty assassin.

2. NPCs must adapt to the player, and not vice versa.

In Assassin's Creed, sometimes it happens that you need to lead a friendly NPC to a certain point while conducting a conversation. Or just go somewhere with the NPC. And you either follow the path of the NPC, or risk failing the mission. In general, the player wants to have some kind of marker, as in the previous paragraph, and that the NPC accompanying the player adapts to his behavior.

An exception may be cases where the player MUST see a particular location, for example, in training at his base. Or if you need to track down a hostile NPC, then the player must adapt to the NPC to perform the task.

3. Additional tasks must match the character. It is better that they do not determine the style of the game.

Oh, additional tasks. In Assassin's Creed III there is a whole bunch of them for every taste.

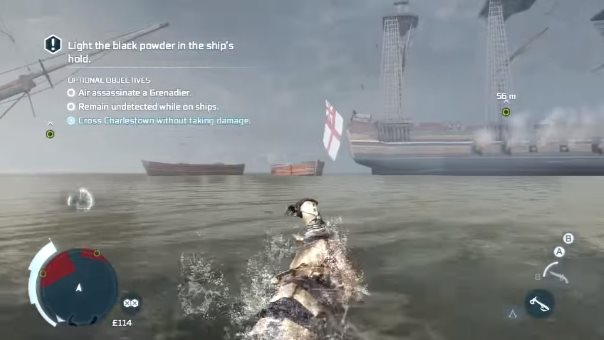

There are arbitrary ones that have absolutely no meaning. For example, in the mission “War is coming” (Conflict Looms) there is an additional task - to kill a grenadier in a jump on one of the ships. The trick is that there is an additional task to go unnoticed. Therefore, to perform this task, you must first clean up the entire vessel, and then prepare for the kill in a jump. But the main task is to burn gunpowder and destroy all the ships, so stealth and kill in a jump seem unnatural.

There are also tasks contradicting the character. In the “Angry Chef” mission, we must quietly kill five guards (non-lethal knockouts are not considered). At the same time, Connor is trying to convince the disgruntled chef from the name of the mission that violence is not the solution. There is a clear contradiction. All this is complicated by the fact that in Assassin's Creed, the performance of additional tasks is considered “full synchronization”, i.e. performing missions in the way the ancestor did. And Connor looks like a hypocrite, stating in the cut scenes that he is against unnecessary violence, while the additional tasks in many missions are connected with unnecessary violence. And the excuse for Animus "this is not necessarily a repetition of what happened" in this case does not fit.

There are also tasks that force a player to complete a mission in a certain way. For example, in the Battle of Bunker Hill (Battle of Bunker Hill) there is an additional task to kill the victim in the jump. The problem is that it immediately forces the player to go through the playing field in a certain way, without trying to improvise and search for his own way. And this is in a game where freedom of choice and style of play is considered important.

Of course, there are good additional tasks. For example, in the Battle of Monmouth mission during the retreat there is a side task - to prevent the execution of patriots. This fits the character — Connor would not allow his allies to be executed during the battle. This adds complexity - there is a time limit for the entire retreat and the player must have time to complete the main and side tasks on time. And the task does not determine the style of the game, it does not require "kill the executioners from the bow" or something like that. In fact, the player is not even obliged to kill the executioners, he may simply distract them so that the patriots can escape.

As an exception, there is a good example of the mission “Devotional Trust” (Broken Trust), in which an additional task is to stop the people of the tribe in non-lethal ways. Yes, the fulfillment of this task determines the style of the game, but it also corresponds to the character of Connor - he would not have killed his own fellow tribesmen.

In general, I think it is best to do additional tasks as side tasks, rather than ways to accomplish the main task.

4. The failure of the mission should not be the end

In the ideal case, you need to strive to ensure that the failure of the mission would be only the death of a player. If you have retired from an ally or have been discovered, the game should not stop, but change its context. If you are found, then you enter the battle and the situation changes (for example, the protection of your victim increases). If you are far from an ally, then he or goes for you, or, at least, stands and waits for you.

A good example in Assassin's Creed III is the Hostile Negotiations mission. This is the kill level where you need to eliminate William Johnson. The player does not fail the mission if he is discovered (however he fails the additional task - to kill Johnson imperceptibly). The player does not fail the mission if Johnson sees it. In this situation, he begins to run away and the player must pursue him. Also, the mission is not failed if all the locals are killed in battle (however, an additional task will be failed).

The failure of a mission can become mandatory when a change of context is impossible. For example, if an ally is killed. Or if the detection is not valid from the point of view of the plot. Perhaps this is not ideal, but is understood by the player and makes sense to him.

5. Try to use as many tools as possible in missions.

Assassin's Creed III provides the player with quite a lot of tools, both items and abilities of recruit-assassins. The problem is that most of the mission time is not designed to use these tools.

For example, assassin recruits have the opportunity to dress up in the uniform of the guards and imitate imprisonment. This is a good rethinking of the capabilities of the Monk / Courtesan from previous games. The problem is that this ability, which appears in the second half of the game, is actually only used in the side mission in which you receive it. Although it can be used to capture forts, it is not useful in main missions. Therefore, it is simply inactive.

An example of a mission in which there is an excellent use of tools is The Tea Party. In the first part of the level you need to clear the playing area of the English soldiers. Of course, you can complete the task by simply engaging in melee combat, but you can also use smoke bombs and poison darts to simplify the job. It is rather strange that the ability of the Riot recruit-assassin, obtained earlier in the game, is inactive here. But the abilities of other Boston recruits are available, and Marksman can be used to strip the area.

The second part of the level is built to protect the playing area on the ships, while the allies throw out tea. Here the player can use the recruit-assassin combat abilities, such as Bodyguard or Calling, to kill the attacking British. This, as I recall, is the only mission in the game where I used bomb traps. They can be placed strategically on the boarding boards to get rid of the attacking enemy, while you are fighting at the other end of the game area.

For this principle, I can not think of exceptions. Because it is impossible for each mission to have the opportunity to use all the tools available to the player. But it seems to me that it is worth making sure that there are enough reasons for creating tools at the levels to be used throughout the game.

There are, of course, other lessons learned from Assassin's Creed III, but they, as it seems to me, are more applicable to level design in general. The above are especially important for missions in the open world, although now I think that they can be used for level design in general. Having listed these principles, I want to make a brief overview of where in Assassin's Creed III there is good design and examples of open world missions, and where is bad.

Examples of good mission design: part 6

In the missions of part 6 there are some miscalculations, mainly in the additional tasks. But they are still a very good example of an open world mission design.

There is "On Johnson's Trail", the mission of which is to research Boston and perform side tasks in the process of moving to an open protected area with smuggled cargo that needs to be destroyed. Also, you move around the game area and perform interesting tasks for you.

Then comes “The Angry Chef”, which is a good example of the escort and protection mission. Since at the previous level the player had a lot of freedom, a more linear approach does not interfere with the game.

There is also The Tea Party, starting out as a free-sweep scenario for the gaming area. Then she goes into a situation of active confrontation with the enemy, in which you need to throw out the tea boxes, while protecting your allies from the attacking British soldiers. This and the previous missions give less freedom, but they still have variability and choice in the context of tasks, which is important.

The part ends with Assassin's Creed's classic assassination mission in Hostile Negotiations. You know your starting point and the location of the target, you can reach it in any way, eliminate it and escape.

The player passes this part and gets used to it. This is where Assassin's Creed lies - in the sensation of the plot in the open world. This part is completely interesting and is probably my favorite part of the game.

Examples of bad mission design: part 8

Now we will look at part 8, which I can call my least favorite of the whole game.

The first mission, Something on the Side, shows the first visit to New York, but the player cannot explore the city at all. As soon as you get into it, you must follow an ally along a given path (or fail a mission). Immediately after this, you need to track down the victim along a given path (or again fail the mission). Then you need to pursue another victim through the city or, of course, fail the mission. After capturing the victim, you do not go to the exploration of the open world, but go to prison.

This is the scene of the Prison Bridewell Prison mission, long and boring. You need to eavesdrop on your camera, then sleep, then talk to the NPC and play a board game with him. A bunch of cases in the same place. After all these worries, you can't even run away.

The next mission is the Public Execution. This is a murder mission, but it consists of a linear path through the crowd, which you first need to go through, then look at the cut-scene, get together quickly and reach the victim. And after completing the mission, the player is teleported to a completely different place outside of New York.

This part introduces the new city, but does not allow to explore a single inch of its territory. Beyond the linear passage is a linear passage. The player takes away all the tools and most often there is only one way to perform this or that action. In my opinion, this is an example of how not to do missions in an open world.

In conclusion, I want to say that the basic design principle of the open world missions that I took from Assassin's Creed III is to provide the player with the opportunity for self-expression in the context of the mission. Ideally, the context should be as free as possible, but for variation one can limit its limits and introduce additional obstacles where it makes sense. In this case, you should not completely take away from the player the opportunity to act independently.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/317434/

All Articles