Interweaving the narrative into the procedural worlds

For three years now I've been blogging my new roguelike project. The history of the game in it is given quite a few discussions, which reflects its small informative role and importance in the process of developing the alpha version. In fact, the mediocre and beaten-up science fiction story 7DRL , set out in the game jam version, was followed by a restart of the project in 2013, and the first extension of the development timeframe occurred only because of the embodiment of a unique detailed history. Everything that happened later, in one way or another, serves to support the narrative.

Now that this part of the Cogmind world has taken shape and is close to completion, I would like to explore new territory and speculate on how and why integrate elements of history into a genre that is traditionally rather poor in plot.

Part 1: Value

What for?

Naturally, the first question here is “why do we need a story?” “Bagels” is not exactly RPG, and they rarely emphasize storytelling. In fact, there is even the danger that the story will ruin or destroy what makes the roguelike interesting in the first place (we will touch on this point several times).

')

However, I argue that with careful use, there are several ways to enrich roguelike gameplay with stories, which makes them a potentially valuable addition. Let's look at some of the benefits, which at the same time are the goals when developing a new roguelike.

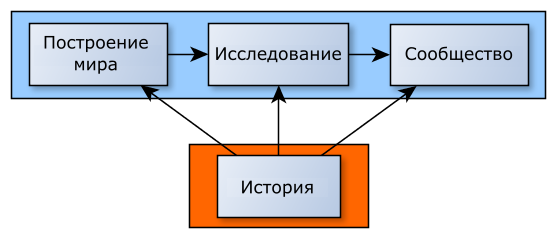

The value of the elements of the story in roguelike, a brief overview.

Building peace

The theme and entourage define the starting point of the roguelike for selecting materials from sources, but creating a story on top of them (ideally with a lot of storylines) takes the game to a new level. History requires that the participants have motives and goals. The whole world feels more alive if the participants in the story have more difficult goals than to “get to the player and kill him”. Of course, mechanics and basic content (for example, descriptions of participants and objects) can by themselves significantly improve the reflection of nature and the state of the world, but a full-fledged scenario strengthens them in the most powerful way: through action.

Observing the legend (lore) of a game in action enlivens it, adds something new between the lines. From the very beginning, this approach was especially important in Cogmind, because it enhances the player’s immersion, his focus on the sensations I was aiming for. And from the point of view of development, the same desire to make everything animate makes the creation of the game more profound. When the world began to expand, I often wondered: “Would it be interesting if a player actually visited this place? Or did you meet a certain character there? ”And suddenly they turned into the game. As a result, the world over time has become much more full. Each new element strengthened the rest.

Significance and purpose

Roguelike, filled with elements of history, also receive additional levels of significance on top of what is happening in the world, creating a contribution to “epic sensation” - the world is definitely bigger than a player’s character who can have a higher goal than just a “killer rogue” ". In the 7DRL version, a brief preface slightly outlined the prerequisites for a straight-forward dungeon crawl. But I can’t imagine today's Cogmind without its deep and exciting history. Brand new maps and interactive NPCs have been added so that the player can influence the world in many ways, because it made sense in the context of a larger narrative.

Interactive stories are often a good source of memorable experiences. They can be even more complex and powerful than standard roguelike. After all, history can stretch into many places and events. For example, in Cogmind, a player can go to a place where hell is going on, which, in turn, affects other places. Event details may depend on other player actions. History connects individual locations and characters in different ways, creating the scale of which few “bagels” are capable of. (There is plenty of room for innovation!)

When exploring the resulting web of opportunities, individual player steps add many intermediate targets. This means that the player has more to do, which in itself raises the quality of the roguelike game. Such tasks are themselves rewards, events that are different from the simple killing of monsters.

But it is worth noting that, depending on the implementation (discussed in Part 3), the presence of the story does not have to force out the player’s own narrative. I noticed that, like in other roguelike, in our game, players themselves create small stories. The stories are based on danger, unexpected turns, and salvation from imminent death. They occur in separate encounters with opponents, even if the game does not have a deep plot. This is important because it constitutes a valuable part of the roguelike experience, and demonstrates that you can add a story to the game without drowning in the emerging mini-stories created by procedural generation.

Therefore, along with every minute survival and long-term development strategy, the story becomes the third potential goal of the player. This advantage works at the level of individual players and communities.

Creating interest and discussion

Research is a fundamental part of roguelike, be it a mechanic, a new content or just unexplored areas on a procedural map. The story gives the player more reasons to be interested in the events of the game world, in addition, it captures and encourages research to find answers and reveal secrets. The game doesn’t really need an extra “peppercorn” to enjoy the process, but it’s nice to create another channel through which players can connect with the world.

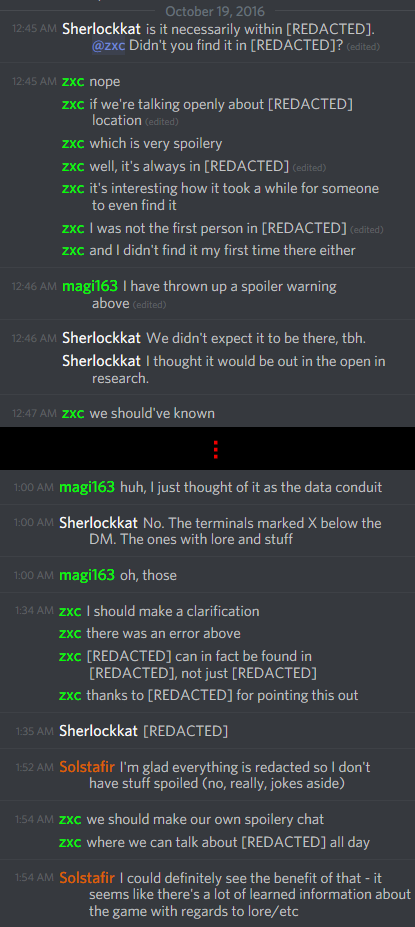

This feature works on a broader level: from two friends playing together to large communities. Elements of the story become common topics for discussion, allowing players even in a single-player game to share experiences in the same way that they discuss mechanics or strategy. Legend, locations, NPCs, motifs, factions and other elements become part of the “common language” mastered by players during a gradual exploration of the world and events occurring in it. Anyone who is learning a new release or not reading spoilers in the wiki will find a lot of food for thought. From my point of view, it will be very funny to watch the community trying to figure out what is happening in the game.

Players spoiler the secrets of the game in the general chat

There are other aspects that contribute to the general discussion and increase the level of interest, both for people not participating in the community and for the community itself:

- Secondary characters and events that players are talking about. Some of them are quite memorable, for example, an “annoying renegade”, because everyone recognizes a certain NPC without a specific name.

- The story adds another change in passing with different generation of the world. Different players may have the same or different approach to the same set of history related events.

- Particularly important are relatively rare events, including those built on a chain of events. There are quite a few comments like: “I saw ...!” Or “Have you ever seen ...?!” Only last week a player opened an important story event for the first time, added ten months ago.

All this means that there is a great value in building a roguelike based on a good story, of course, if it is written correctly. We will come back to this later.

Part 2: Characteristics

Having defined the aspects of roguelike that will benefit from the addition of elements of history, we turn to the difficult part: directly to its creation.

Of course, there are many ways to spoil the gameplay roguelike history. Therefore, the next step is to define the characteristics of a good narrative, proving that for permadeath and a procedurally generated world, history is not contraindicated.

Story

Of course, it is based on the need for an exciting story! This is the most important thing - if the story is boring and standard, only the roguelike gameplay will remain in the game. To focus on one thing is good, but it will be even better if you add something from the above. What story can achieve such goals?

As with all game design, integrity is key. A meaningful history thanks to a holistic internal logic reinforces the concept of the entire world order (see Part 1). Having only partially got acquainted with the plot, the observant player begins to intuitively anticipate events. For example, where to find some object or character, what will be affected by a certain development of events, etc. He will fill the gaps in knowledge with what seems reasonable. Players may not always be right, but at least they will have that choice. And for someone, such a process is interesting in itself. In addition, to err is also fun, because this is how an element of surprise arises.

Therefore, the most useful story in this regard will be the one that will actively use the cross links between different game forms of content, NPC dialogues, relationships, behavior and the like to help the player's intuition and general understanding of the plot. As a high-quality mechanic is the basis of the gameplay, so a good story holds the content together.

Cross-linking also avoids one of the biggest pitfalls that destroys the value of history: linearity. A linear story is almost never suitable for a roguelike, unless it is a specially conceived theme for the game. It interferes with the freshness of each passage, which they strive to provide with procedural generation (besides, players will be very annoyed to meet regularly with the same story after each death!). Instead, try to make the story easily divided into small fragments that can be lived independently of each other and that will remain interesting and meaningful (more on this below).

A complex plot with many intersecting threads will naturally be much more replayable.

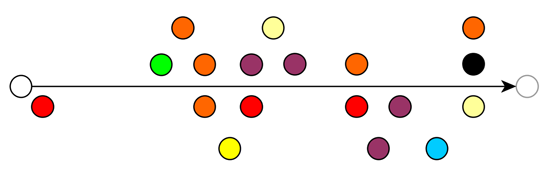

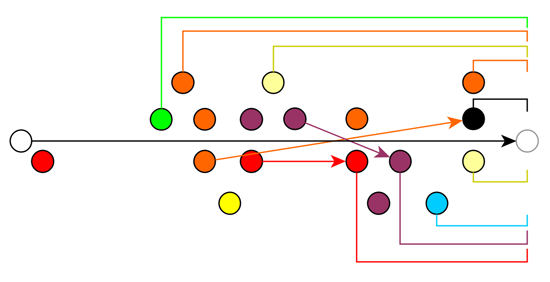

Abstract visualization of potential encounters with major NPCs associated with the Cogmind storyline (separated by color by faction). Start the game on the left, end on the right. Many of these meetings are connected with future meetings, with the player or with the world as a whole.

Notice that the story plays a smaller role at the beginning of the game, which is the most frequently replayed segment. If there is too much emphasis on static elements, then this can annoy the player. This is especially true for Cogmind, which is devoid of the initial character generation phase, but in other games you can try to use the very beginning to provide the player with a wide selection of history-related options.

History and gameplay integration

Events related to the story should be significant not only for the game’s players, but also have a real impact on the rest of the game, creating consequences for the player’s actions at a higher level. In most of the bagels, the feedback loop is quite brief - fight in battle, rest, raise the level, then explore the world until the next battle. Large and small elements of the story can be integrated into the gameplay itself, adding uniqueness to the repetition. They are elements that a player can choose as a long-term strategy. Depending on what the player decides to do, the plot can significantly affect future events, or not influence them at all, or be something intermediate, or just give an instant effect. When a player becomes familiar with static plot elements, he may or may not want to use a chain of events in future passages, depending on his plans, current conditions and time of events.

Therefore, the story here is not just for the sake of history, it provides the basis for additional long-term feedback cycles. And for this reason I tried to ensure that many aspects of the Cogmind story have useful (or at least interesting) consequences for the player. Another dimension added to the world makes the gameplay deeper than in the usual "clean" dungeon crawlers. Despite the presence of static elements, this approach has proven its vitality after several repetitions. In addition, there is always the opportunity to expand the number of options! Even a small number of interactive elements can lead to a wide variety of combinations and effects.

The same pattern of meeting with the main NPC, showing events that have a direct impact on further events (arrows) and have a relatively significant long-term impact on the gameplay (without arrows).

All this is optional!

Notwithstanding the foregoing, one of the most important characteristics of the history of Cogmind is that it is completely optional .

The game should be fun, not requiring the player to go through the story or even pay attention to it. Newbies in the game can go through it from beginning to end, just thinking, “So, okay, I'm a robot, and other robots want to kill me. Piu-piu-piu! ”In fact, any point in the plot schemes can be avoided or ignored.

If you do not poke a player in the history of the nose, you can reduce the tension between the static elements and the procedural world, allowing the world to breathe freely. Many people love roguelike just because of the gameplay, or prefer to create their own procedural story about the story, so don't take it away from them. One of the best players in Cogmind played it for more than a year, absolutely not interacting with history, but recently he said that he began to perceive it in a new way when he began to dig deeper.

However, there are other players who, from the very beginning, put the most effort into studying every bit of history, Laura and secrets they can find. To find a huge part of the elements of the legend and history, the player must really be curious. If you leave the story optional, you tune into both of these types of players.

In terms of content, the Cogmind narrative is not technically focused on the player, so it’s much easier to make it optional. I think this is an important factor when creating a roguelike with a story, because it will not annoy the player who chose a simple role.

Another important characteristic is that they communicate with the player, but he does not say anything in return (and he has no obvious choices of dialogues). Conversations are short one-sided connections, outside of which a player can show his reaction through actions and movements in a location. From a design point of view, this may be a limiting factor, but on the other hand, it keeps the gameplay smooth (and the ease of ignoring the plot!). Design constraints lead to more creative solutions, and I enjoyed working with them.

Summing up, I will say that in my case the ideal story of roguelike is a convincing and holistic narrative that connects most of the content. It significantly affects the gameplay, but interacts with it in an optional way, without interfering with enjoying the game. Other roguelike for other purposes may have a different approach to the elements of the story, or completely get rid of them. But I wanted to create a deeper experience than just “one more walk through the dungeons”, both gameplay and in terms of telling an interesting and meaningful story. It seems to me that Cogmind is successfully coping with this, but we still have a lot of work to do!

Part 3: Methods

Taking parts 1 and 2 as a basis, we will begin to explore the various methods used in Cogmind to achieve these goals, which were taken into account at each stage of the path. This is what I meant by “interlacing”, because the game has quite a few individual components that together reinforce the narrative and reflect it.

Structure

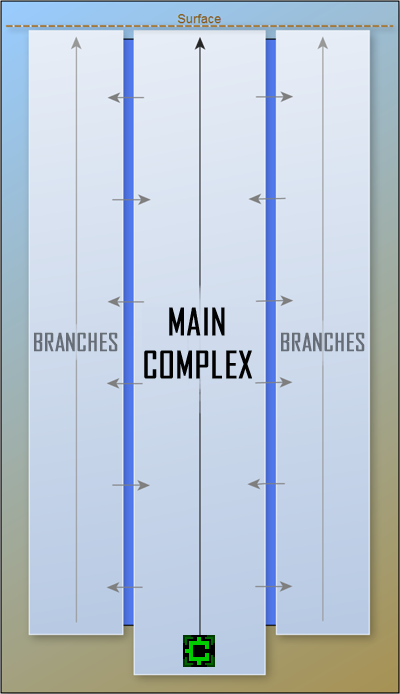

I believe that when creating a roguelike with a rich history, the most fundamentally important aspects are the outline of the world and the ways to navigate it. In a non-linear history, it is reasonable to create several simultaneously accessible locations, be it something like an open world or maps connected by a network. Cogmind uses the second option. I divided the world into areas belonging either to the central complex, or to its branches, which inevitably lead back to the complex. (I covered this and several related topics in last year’s World of Robots post.)

Simplified scheme of the world Cogmind. Upstairs - the surface in the center of the main complex, on the sides of the branch.

An important difference between the two types of areas is that the story only applies to branches. This means that the player can spend most of his time on the direct route to the surface and the end of the game, and even never touch history. There are no NPCs or dialogues on this route, and anyone who wants stories will know where to find it.

The branches are structured in such a way that more history-oriented areas are usually located deeper, and there is a quick way to get back to the main complex if the player is not interested in the story (or it is too weak, because areas with history are more complex!). In general, this structure is a key element of “non-binding”: players are not required to engage in history.

Most of the players after some time begin to be interested in history, but this happens gradually. Thanks to this, it is possible to keep the world for new players more simple, at the same time opening up additional opportunities for more experienced ones. In fact, for the best players who are still not familiar with the story, additional strategic opportunities arising from the integration of elements of the story with the gameplay are one of the main motivators for research. For example, there are “manual hacking codes” that often link unrelated areas: by recognizing a code in one area, you can get advantages in another.

The function of using help with a manual hacking code is introduced in the tenth alpha version. The list shows where and from whom each code is received. Also, this function is suitable for hacking robots (the following picture).

It is critical that the player can not return to the early areas. Choosing one route naturally closes one or more others. Cogmind will be quite a difficult experience compared to the open world or the game, where you can return to previous maps!

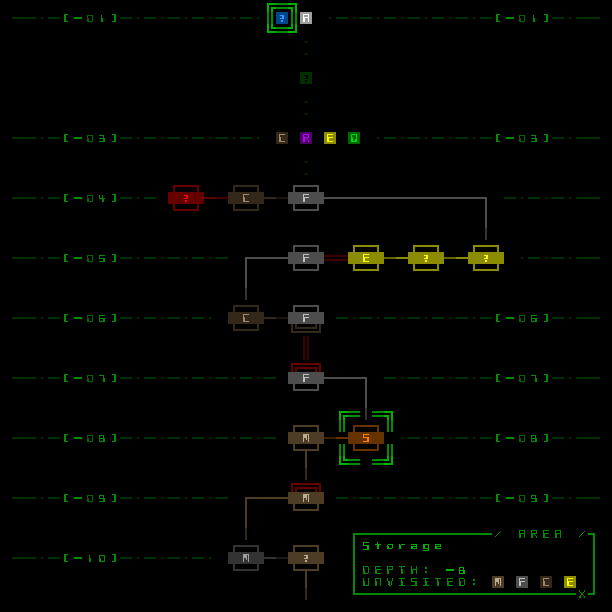

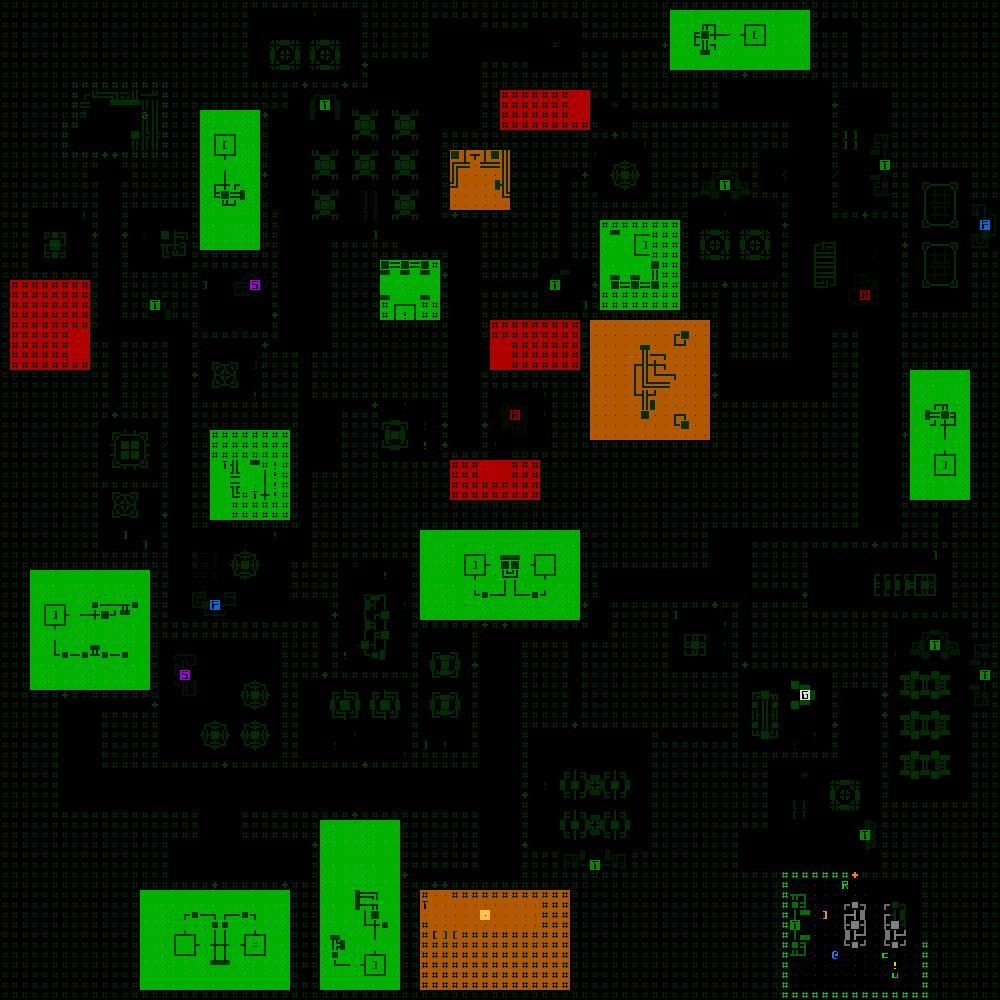

An example of a game world map marking a player’s path from a deep dungeon to the surface.

Due to the constant striving of the player forward, the designer has a greater degree of freedom of freedom, ensuring greater control of the game by the developer. Control, in turn, facilitates the creation of a more focused and interesting gameplay. Good balance is important in roguelike, but the general flow is also important (this is not so relevant for roguelike sandboxes, where the players themselves create a flow for themselves).

Although all branches are accessible from any world, the inability to visit them all in one passage gives the player interesting choices. These options continue to expand when the player learns more about their structure and approaches the end of the game.

ENT and dialogues

Cogmind has quite a lot of lore appearing in various forms and giving the player different channels for learning the history.

Games naturally include the legend, the backbone of the story, the corresponding theme and entourage. For example, information is provided through books, tombstones, traveler magazines, etc. To the limit this is brought in some computer RPGs that allow you to read letters and text on almost any object. In traditional roguelike environments, a richer and smoother approach is better suited. We limit the ENT to a small number of easily recognizable sources.

One of the main sources of Cogmind's Laura is terminal recordings (a very rare approach in science fiction games). Terminals can be hacked for background information on various topics. They are organized in such a way that the closer to the surface and the end of the game, the deeper these topics look at history. Most of the entries are written in terms of one of the factions. Terminal entries in higher regions may contain other points of view.

However, not all parts of Laura are equal. Some are more common and easily accessible, while others are in special areas. Therefore, the disclosure of the entire Laura and the investigation of the story is something like a puzzle that takes time and several passes (and a player is good enough to put them all together). The contents of the records can also be sent to other records, which, in turn, can be hacked directly from the same terminal. This gives Laura a network form that motivates the player to explore as many topics as possible.

Hacking the terminal's record through direct links and manually.

If players for some reason do not want to break terminals (and this is quite simple, because the terminals have many other useful functions), then the story will not affect them.

ENT is also contained in the “robot analysis” records. Such records give real advantages to the players who have hacked them (accuracy modifiers and evasion against this type of enemies). In addition, they describe the components of robots and sometimes contain plot particles about the purpose or history of each robot.

Perhaps the most unexpected from the point of view of Laura was the lack of a description of objects in Cogmind. Many games even without focusing on the story (or no story at all) add some text to the descriptions of the items, thus setting the tone of the game. In Cogmind it would be a huge amount of work, because there are so many items in it! And more importantly, I do not think that such a text "seasoning" immediately creates a correspondence of objects and themes. Even the best description of objects would be spoiled by the feeling that the player is a robot, and does not play for a robot. In addition, there is not much space to display this information, so you would need a separate window. (However, note that dozens of items have their own ENT in the form of terminal records, so descriptions are present, but not in full size.)

Dialogue

ENT can also be studied by listening to the NPC, usually after touching them, but sometimes just seeing them in sight. The content of the dialogues is often insignificant and represents pieces of opinion from various points of view, complementing the ENT. Also there are general tips on the game and recommendations on tactics and strategy. In this case, I tried to write them so that they looked logical words of the NPC (spoken to a stranger or just in a certain place or situation). I tried to avoid banal dialogues like: “I am NPC No. 23 and I exist only in order to transfer this extra-contextual information to you”.

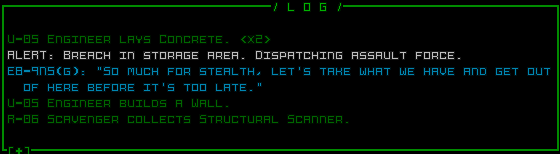

An example of the dialogue text in the message log.

As I mentioned earlier, all these NPCs are far from the beaten track, but even there their dialogues are very unobtrusive. They simply appear as text in the message log and for a short time below the map screen.

The NPC speaks while the player is nearby.

There are also several examples (this system has not yet been fully implemented ...), in which a brief description of a scene may emerge from the edge.

The modal dialogs used for important NPCs and events in particular areas are a bit more intrusive. However, the frequency of their appearance is reduced to a minimum. A player can quickly click on Esc or close a window, the contents of which he already knows (or does not cause windows to appear at all).

For more on UI dialogs, see this old post .

Picking lora

After preparation and insertion into the game of the greater part of Laura, a new valuable function was added: the Laura gathering interface. This is the central repository for all lora collected by the player in all passages of the game. The "ENT" includes messages from most NPCs and terminal records. The content is categorized by region and arranged in alphabetical order. A player can go to the desired section by simply pressing the first letter of the record he is looking for, or scroll the automatically loaded text down.

Interaction with UI collecting lora (here it is filled with garbage so that there are no spoilers).

To simplify the collection of lora, terminal records that have not yet been read by the player are marked with a "!" directly at the terminals from which they are available. In addition to collecting all the information in one place, there is a percentage indicator at the bottom that shows some other advantages of this system.

, . , () , !

« » ( ). , - scorehistory.txt. . .

Developments

Cogmind, , , — . , , .

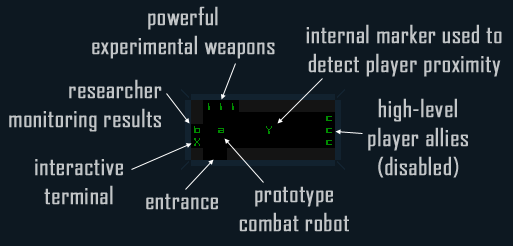

REXPaint , «» Cogmind. . , (, )? . ( !) - , , , . , . , , . .

, , . , , - . — .

. , , :

, .

, . , , , , , . roguelike, .

Additional elements

«» . , , .

- NPC, - , . Cogmind - , , , . , , . , , . , . , .

- ! , . NPC - ( !). , — (, « ?» « ...»).

- . Cogmind . - , - . . , . (: Cogmind , . .)

Conclusion

roguelike- , . , — . . , Cogmind , . !

, — , . .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/316126/

All Articles