5 tips to improve game animations

Hi, my name is Dave Bleja (Dave Bleja), I work in the studio Volnaiskra. For the past 3 years, I have created Spryke , a fascinating and sophisticated platformer about deep-sea marine cyber fish exploring sushi wonders.

As the only permanent member of the Spryke team, I was responsible for many parts of the creative and technical process. Some tasks are tedious, but most are fascinating. My favorite aspect was animation, and I want to share with you five tips on animation that I have developed over the years.

First tip: sometimes "quantity" means "quality"

The phrase “Less is more” has become such a worn cliche that my suggestion may seem outrageous. Well, hold on. Sometimes less is ... less!

')

Quality is no substitute, and as artists we must always strive for it. Knowledge of anatomy, physics and lighting of the real world will help you improve game graphics; lack of knowledge will hurt her. But it turns out that one of the most important building blocks of quality is a simple quantity. And this is especially true of animation.

At a fundamental level, animation is quantity. The animator creates hundreds of still images that are so connected with each other that the brain can no longer process them separately. This is how the magic of movement is created. The same principle is often applicable to creating high-quality animations.

For example, take these bubbles. They look nice, right? (Of course, it is, because they are taken from our awesome game Spryke!)

Animation

So what am I talking about? Oh yes, bubbles. They look good, but the basic graphics of the bubbles themselves are incredibly simple - in general, they are just circles. They look beautiful because of the quantity. But not only due to the number of bubbles, but also a large number of processes occurring with these bubbles at the same time. Let's look at them in detail:

Animation

(1) Bubbles with different transparency and size;

(2) + slightly different shapes;

(3) + randomized oscillations and a smaller size at the very beginning;

(4) + randomized trigonometric motion (i.e. along a curve);

(5) + multiple sources;

(6) + the refraction of light in water, the bubbles move and split into smaller ones when colliding with a player.

Each stage of this process is simple (fluctuations and deviations require a little knowledge of geometry, but nothing particularly complicated). None of these stages individually is something impressive or believable. But by joining them all together, we create a complex and convincing whole. When we got to step 6, there is already so much around that that consciousness cannot track it all separately, and the individual animation components merge into one beautiful and dynamic whole.

I want to emphasize that this principle applies not only to multiple objects, such as bubbles. The same “quantity creates quality” approach applies to the animation of anything. Most of the objects of nature moves in various, often barely noticeable ways. Carefully looking at the person standing motionless, you will see a dozen small movements, from blinking and swallowing to the movement of the hips. Watch the person walking - almost every part of his body and face moves in a special way, and not just his arms and legs.

In general, the more it happens during animation, the less mechanical it looks, and the more organic and interesting it is. This approach can even be applied to mechanical objects, such as this door:

Animation

About a dozen processes occur in this door animation, and most of them are very simple: parts move up and down, light bulbs flicker, screens burn and change colors, plus the basic effects of smoke particles. But due to the fact that these simple movements are contrasted with each other (some elements move up or down, others to the sides; some flicker, others burn) and, because of their slightly different time, they all together create a complex whole.

The limit to which you can add complexity to an animation depends in part on the type of animation used. In this regard, the animation in the engine is more limited (although it has other advantages, such as randomization and dynamic response, see the bubble example).

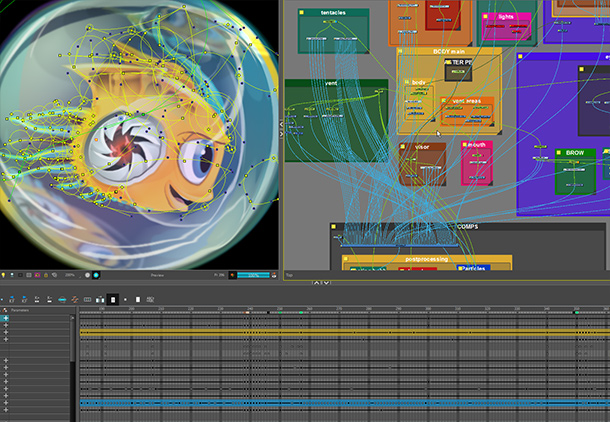

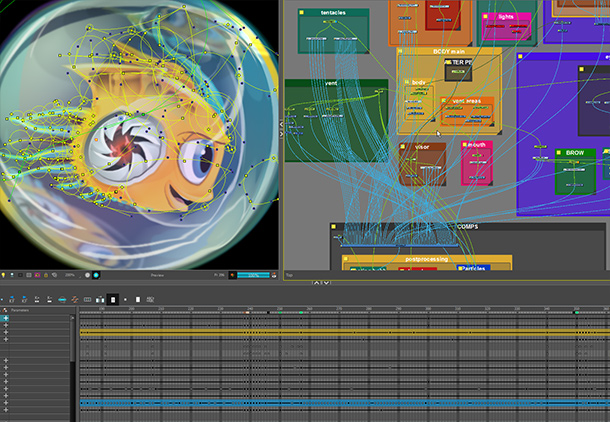

Spryke itself uses pre-rendered animation, which allows me to increase the complexity compared to what is practically possible in the engine. To create a good pre-rendered animation, I strongly recommend you a program like Toon Boom Harmony Premium, which allows you to rig characters with nodes.

The Sprayk Fish, although the game does not exceed 70x70 pixels in size, is composed of more than 30 moving parts, controlled and connected using approximately 250 individual nodes. This allows you to create very flexible and detailed movements in various postures.

Second tip: Ugly frames can make animation better.

As we know, most of the animation magic happens on the border of the conscious and the unconscious. This is a vague area in which the animation “dissolves” in the subconscious and becomes larger than the sum of its parts. But in some cases, the elements of animation for efficiency should not be monitored at all by consciousness.

A good technique to create more charm and attractiveness of animation is perfectly mastered by Warner Bros animators: creating a single frame with great exaggeration. The trick here is to choose a moment of collision or fast motion and insert one (and only one) frame showing the pose in an exaggeratedly caricatured state. With conscious observation, this frame will look excessive and inaccurate. But when he “feels” in animation, he raises the rest of the animation to a higher level.

Animation

One distorted frame of a frightened snail does not look very likely in a stationary state (i.e., when viewed consciously). But if you close the delayed version with your hand and look only at the left side, you won’t understand how “wrong” it looks. Instead, he adds some more pleasant animations.

Animation

In this exaggerated frame of the coyotohoke (which I named so in honor of the Sly coyote !), I distorted different parts of the body so that the illustration actually “broke off”. But this discontinuity is not really recognized in the animation, so this frame simply enhances the drama of the moment.

Third tip: fuzzy, blurry frames can save precious milliseconds

Also, as you can add additional charm to the animation with the help of a trick with a cartoon frame, you can add even more dynamics with a fuzzy, “blurred” frame. This technique allows you to create a very fast movement for a small number of frames, which fits perfectly into many game scenarios, in which control responsiveness is paramount.

The trick is to take two external motion frames, and join them into a blurry third frame, which is inserted in the middle.

Here you need to remember a couple of principles. First, the fuzzy frame should look like a mixture, and not the average between the initial and final frames. In other words, the region it overlaps should approximately correspond to the region that can be closed by both the initial and final frames (this will make the object in the blurred frame larger than usual, but this is normal).

Secondly, special attention should be paid to the small key components of the character, such as the eye. If the positions of the eyes in the initial and final frames are very different, then placing it in the middle in the middle frame, we get a jerky animation that has lost its smoothness. Therefore, in this middle frame, you need to "blur" the eye from the initial to the final position, as in the example below:

Animation

This frame of intermediate motion looks ominous when consciously viewing it, but it provides a very fast and dynamic transition when animating (close the right part of the image to see this!). This creates the feeling that Sprayk quickly touches the wall. Oiled eye helps the eye to move smoothly from the initial to the final position.

Fourth tip: remember that the nine old men did not play video games

If you have not heard about the 12 principles of animation , you must get to know them. These are logical principles developed by the masters of Disney animation, the so-called "nine Disney old men". But in the context of certain video games, adherence to some of these principles can be problematic.

Take the highly effective principle of anticipation. This principle implies that the majority of movements must be preceded by a movement in the opposite direction: a baseball pitcher, throwing the ball forward, first moves his hand backwards; the screaming person first breathes in and squeezes the muscles of the face. The inclusion of such anticipation movements in the animation makes them more believable and enjoyable.

Unfortunately, this principle sometimes contradicts the needs of game design. When a player presses the jump key, he expects the character to jump immediately. If you anticipate a jump with several frames of anticipation, then it may look better, it will feel worse (less responsive). The same applies to the principle of mitigating the beginning and end of the movement: the animation of a jump with a significant softening will be beautiful, but not responsive.

Therefore, in many games, these principles are ignored in some animations. Even in beautifully animated games like Rayman Legends. Note: Reyman has a lead when hitting the ground, while the NPC has a lead when jumping, but when it comes to Rayman's jump animation, he suddenly loses his visual "rubberiness" and instantly comes off the ground, like a chess piece raised from the board. This leads to less high-quality animation, but also to greater responsiveness, and therefore, to the best feelings from the game.

Animation

In Reyman's jump, responsiveness was set above animation, and in the original Prince of Persia the opposite situation. Notice how when jumping off a cliff there is almost a full second lead. It looks good, believable from the point of view of physics and anatomy, but creates a delay that the player must take into account with each jump.

I think this was the right decision for Prince of Persia, which impressed us with an unprecedented level of realistic animation. But today, many players will not accept this.

Prince of Persia

When animating the Spryk jump, I compromised and tried to include a bit of anticipation in it, which did not interfere with the gameplay. As a result, I made Sprike jump instantly, but I laid a bit of anticipation in the animation. Therefore, in motion, Spike feels pre-emption, despite the fact that she jumps immediately after pressing the jump key. This is not as effective as a few frames of pure lead, but it seems to me that this is a worthy replacement.

The time and movement of these two sequences are the same. In the animated version, you can see how the whole mass of Spryk jumps instantly, just like in the version without animation. But inside her animation there is a bit of anticipation: she pushes off a bit, moving the weight from her center back. This, in turn, causes its antenna and scallops to move forward a few frames until they are thrown back.

Notice, however, that when most of her body is repelled with a slight lead, the opposite happens to her eyes: they instantly move forward and move to the right direction. It turned out that it helps to emphasize its instant upward movement, even when the rest of the body shows weak signs of pre-emption and delay.

Animation

In addition to pre-emption, the principle of mitigating the beginning and ending of movement ( slow in and slow out , which is easing ) can influence the sensations of the game. Take a look at these two animations from The Witcher 3:

Witcher 3

It is difficult to deny that the animation on the left looks better: the movement is more convincing, it has more weight and masculinity. The movement on the right is more energetic, but it looks very unrealistic and stupid. Geralt looks easy, like a feather, and in the world it seems as if a part of physics is missing. Many different processes take place here, but the main one is a less pronounced softening of the beginning and the end, which leads to Geralt’s zigzag movement almost without inertia.

On the left is the version from which The Witcher 3 started the game. But due to the requirements of CD buyers Projekt Red, the patch was replaced with an alternative movement (on the right). When I first tried an alternative movement in the game, I was shocked - it was so detrimental to realism and immersion in the game. Suddenly, the game, full of harsh degree, became like an arcade Darksiders.

Although it broke my heart a little bit, I left this animation for the rest of the game: the new animation felt better. And as a player, and as a game developer, I’m entirely for immersion in the game, but the needs of responsiveness to management and game sensations are so important that even I didn’t want to disturb them.

Fifth advice: create mechanics, then animation, and again mechanics

Animation is not just superimposed on top of mechanics — it fundamentally changes mechanics.

Important knowledge about game design: even such old games as the first Mario were first created without graphics, from blocks alone. As soon as it becomes interesting to play with these ugly blocks, you have to start thinking about improving them. Otherwise, you can confuse beautiful graphics with interesting gameplay and as a result create a game that looks much better than it is played.

Spryke spent 3-4 months in the form of blocks. I knew that I wanted to create a platformer with especially fast and attractive movements, so I endlessly experimented with inertia, acceleration, jumping curves, mechanics of hitting the ceilings and hovering in the air, until the movement of this square block on the level was excitingly interesting.

At this stage, I still had no idea what the Spryk character would be, and its appearance gradually grew out of the requirements of the abstract mechanics of this unit. It became clear that for fast and fast movement the best shape would be a square of 50x50 pixels. So when I started to design the Sprayk, we knew that it would be small and similar in shape to the ball in order to move briskly in any direction.

Then we performed many iterations of its design, until the character and his character began to take shape, after which I animated her various movements.

An interesting thing happened at this stage: the playters began to notice how much better the mechanics became. They said management was much more responsive. However, in fact, the mechanics have not changed - we have not changed anything except animations. I realized that my sense of mechanics was complemented by thinking up the animation that was in my head, and the playters were deprived of this opportunity.

The difference can be seen in the comparison below. Without animation, Sprayk looks and feels like a bowling ball. It sticks to the ceiling, as if magnetized, it falls heavily to the ground when jumping. Her jump itself looks like some kind of artificial parabola. When animating exactly the same movement, the Sprayk becomes soft and fast. Her jump looks more natural (maybe even a little longer), and as she strides, she seems to push off from the ground on a spring.

Animation

Technically, nothing has changed in mechanics, although it could have. The animation changed the feel of the game, and Spryke seemed to be a completely different game.

Because animations so powerfully change the feel of the game, there is no point in stopping the design process after they are completed. Instead, it is worth doing a revision of mechanics, looking at it from above: has the initial vision of mechanics been preserved? Do I need to change a few variables? Did the animation reveal something interesting that can be further emphasized by revising the mechanics?

In our case, most of the movements of Spryk felt great - the process was more like the improvement of the mechanics of the first stage than its re-invention. The main exception was the soaring mechanics. At Spryke, there has always been a hover mechanic that allows you to slow down in a fall to avoid danger or reach the platform. But after I animated this mechanic in a bubble, it healed with its own life. The hovering looked so different that it seemed wrong. In the existing mechanics, it was just a reduction in speed that could be turned on in the air, but this new animation of the bubble required something lighter and more springy.

As a result, I redid the mechanics of hovering in the air from scratch. I created a new physical component that allowed me to slide on a cushion with my own impulse, a pushing character. The new “instant” bubble (instabubble) gave a very pleasant feeling, which I can only describe with the word “jerk”.

Instabubble is now one of the most unique elements of Spryke, and the most enjoyable basic game mechanics. And she was born from animation! Or, to be more precise, it was born from the process of allowing a function to determine its shape, and then to improve the resulting shape. First, the mechanics. Then the animation. And again the mechanics.

Animation

Well that's all. I hope you enjoyed my advice, may they be useful to you!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/315592/

All Articles