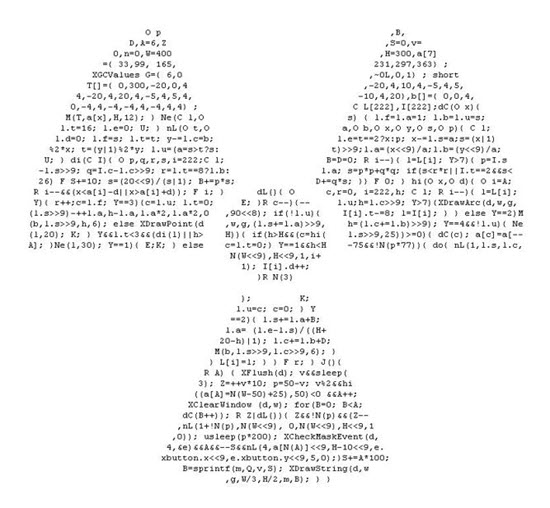

main () {printf (& unix ["\ 021% six \ 012 \ 0"], (unix) ["have"] + "fun" -0x60);}

Having fun, "unraveling" the code in the C language

Challenge: Before you go under the cut, compile the headline of the article in your head, what does it give at the output?

When I once again looked through the book “Expert C programming”, I suddenly came across the section “light relief” in the international competition for the most confusing C code ( IOCCC ). This is a contest for writing as unreadable code as possible. The fact that such contests are held for C, probably says something about this language. I wanted to see the work of participants in this competition. Not finding any information on the Internet, I decided to look for them on my own.

IOCCC was coined by Stephen Born when he decided to use the C preprocessor and write the Unix shell as if in C, but more like the Algol-68 language, with its explicit operator endings, for example:

')

if ... fi He achieved this by doing:

#define IF if( #define THEN ){ #define ELSE } else { #define FI ;} What allowed him to write like this:

IF *s2++ == 0 THEN return(0); FI [Publication support - Edison company, which develops Electronic Transmission Service for Prisoners and implemented viral newsletter information .]

In "Expert C programming" it says the following:

Avoid any use of the C preprocessor, which changes the base language.

One of the first winners in 1987 was David Korn, the creator of Korn shell (what’s wrong with these shell riders?), Who wrote just one line:

main(){printf(&unix["\021%six\012\0"], (unix)["have"]+"fun"-0x60);} That's all. Try compiling this. What will be displayed?

This code will not run on Microsoft (hint!), But here is a link to an online compiler that will cope with this task. It added a few lines to make it work, but otherwise it’s all the same.

The code just outputs:

unix But why? There is something in the code that looks like an array called

unix , but it has not been declared. Then unix is a keyword? Does it somehow print the name of the variable?I blindly tried to verify this by adding:

printf(unix); And he brought me an error saying that

printf accepts char * , not int .When I derived this variable as

int , it became clear that its value is 1. This gave me the idea that it was redefined as if the code were compiled on a Unix system. Searching for gcc source code , I found it to be a run-time target specification . This explains why the code will not run on Windows.unix is just 1. Having rewritten, we get: main(){printf(&1["\021%six\012\0"], (1)["have"]+"fun"-0x60);} So,

unix not a variable name. But then how does 1 [] work? I have seen this before, and this is one of my favorite facts about the C language.

C originates in the language of BCPL. Its creator, Dr. Martin Richards, wrote :

The operator of indirect treatment! accepts a pointer as an argument and returns the contents of the cell to which it points. If v is a pointer, then! (V + i) will refer to the cell with the address v + i. Binary version of the operator! is defined so that v! i =! (v + i). v! i behaves like an indexed view, where v is a one-dimensional array, and i is an integer type index. Note that in the language of BCPL, v5 =! (V + 5) =! (5 + v) = 5! V. The same happens in the C language: v [5] = 5 [v].

In other words, indexes are simply added with pointers, and since addition is commutative, the index operator is commutative. Let's try to change this too:

int x[] = {1, 2, 3}; printf("%d\n%d\n", x[1], 1[x]); Then what is

1["\021%six\012\0"] ? Writing in the usual way, we will see access to the elements of the array through the indexing operator: "\021%six\012\0"[1] . All the same, it is atypical, but it is already clear that this is array[index] , although, as a rule, string literals do not use it that way. But it works, so try the following: printf("%c\n", "hello, world"[1]); Let's rewrite only the first array, while sorting it out.

main() { char str[] = "\021%six\012\0"; printf(&str[1], (1)["have"]+"fun"-0x60); } Still works the same. Looking at

str , I thought about the \0 , which is the null character (or the NUL character?). I thought that string literals in C have a null character by default. Let's see what happens if we remove it: printf("%s", "\021%six\012"); Displays:

%six I use the formatting of the strings

"%s" because the string I am trying to output contains the formatting character % . (A little hint: do not print lines like printf(myStr) when they have formatting characters. The output in %s shown above.)It seems that it still works without a

\0 . Maybe in some pre-ANSI C did you have to add null characters yourself to string literals? I think not, because other lines in the program do not have them. Or does it just look more confusing? Okay, let's leave this \0 .Since we stopped at this line, let's look at the rest of it.

\xxx is the representation of each character in the octal number system, \021 is a control character, and \012 is a newline character or \n , as we used to see it, at the end of the output lines.Knowing that

\021 is just one character, we understand that str[1] is % . Then &str[1] is a string starting with % . So the line can actually be just %six\n , without a control character, which is not clear why you need it here. main() { char str[] = "%six\n"; printf(str, (1)["have"]+"fun"-0x60); } The first line passed to

printf is the formatting line, %s means "put the following line instead of this one". Since this line ends with ix , it can be assumed that the next line passed to printf should somehow look like un . Easily get rid of the array of characters that we used to pass the formatting string, and we get: main() { printf("%six\n", (1)["have"]+"fun"-0x60); } In the next line we have:

(1)["have"]+"fun"-0x60 . There is an un that is contained in the word fun , so let's break it down.See this indexing trick again:

(1)["have"] . Parentheses around 1 are not needed. Again, was it required in old C or made for more unreadable? "have"[1] is a . In hexadecimal notation, it looks like 0x61, subtracts 0x60. Then there will be 1+"fun" .Just as before,

"fun" stands for char * . Adding 1 gives us a line starting with the second character, that is, un . Then everything turns into this: main() { printf("%six\n", "un"); } Here is the readable code.

I like it when semantics plays a big role in code confusion, that is, when, for example, they use a certain word

unix to confuse you and make you think that it is redefined and in some way deduces its name. The symbol \021 is similar to the inverted \012 and can make you think that it is necessary, although, in fact, it is not used. There is also a %six formatting string containing the word "six", apparently, so that you take% s not for formatting, but for something else.Translation: Alena Karnaukhova

Read more

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/313598/

All Articles