Overview of ES6 basic features

JavaScript has changed a lot in recent years. Here are 12 new features that you can start using today!

Story

New additions to the language are called ECMAScript 6. Either ES6 or ES2015 +.

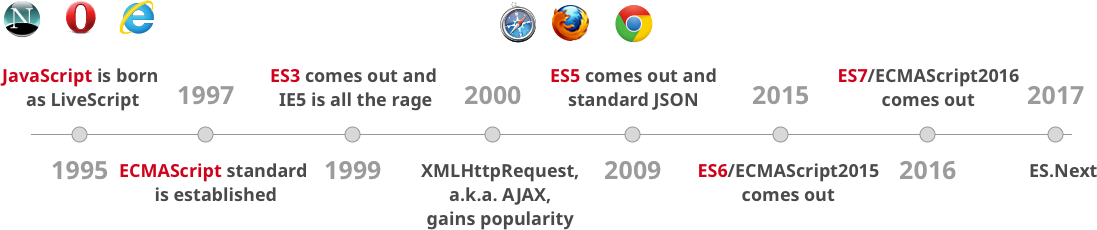

Since its introduction in 1995, JavaScript has evolved slowly. New features added every few years. ECMAScript appeared in 1997, its goal was to direct the development of JavaScript in the right direction. New versions were released - ES3, ES5, ES6 and so on.

As you can see, there are gaps of 10 and 6 years between versions of ES3, ES5 and ES6. New model - make small changes every year. Instead of accumulating a huge amount of changes and releasing them all at once, as was the case with ES6.

Browsers Support

All modern browsers and runtimes already support ES6!

Chrome, MS Edge, Firefox, Safari, Node and many other systems have built-in support for most of the features of ES6 JavaScript. So all of this tutorial can be used right now.

Go!

ES6 main features

All snippets can be inserted into the browser console and run.

Block scope variables

In ES6, we moved from var to let / const .

What is wrong with var ?

The problem with var is that the variable "flows" into other blocks of code, such as for loops or if conditions clauses:

ES5 var x = 'outer'; function test(inner) { if (inner) { var x = 'inner'; // scope whole function return x; } return x; // gets redefined on line 4 } test(false); // undefined test(true); // inner In the line test(false) we can expect the return of outer , but no, we get undefined . Why?

Because even if block if not executed, on the 4th line, the var x is overridden as undefined .

ES6 to the rescue:

ES6 let x = 'outer'; function test(inner) { if (inner) { let x = 'inner'; return x; } return x; // gets result from line 1 as expected } test(false); // outer test(true); // inner By changing var to let we adjusted the behavior. If the if block if not called, then the variable x not overridden.

IIFE (immediately invoked function expression)

Let's first take an example:

ES5 { var private = 1; } console.log(private); // 1 As you can see, private flows out. You need to use IIFE (immediately-invoked function expression):

ES5 (function(){ var private2 = 1; })(); console.log(private2); // Uncaught ReferenceError If you look at jQuery / lodash or any other open source projects, you will notice that IIFE is used to keep the global environment clean. And global things are defined with special characters like _ , $ or jQuery .

In ES6, you do not need to use IIFE, just use blocks and let :

ES6 { let private3 = 1; } console.log(private3); // Uncaught ReferenceError Const

You can also use const if the variable should not be changed.

Total:

- forget

var, useletandconst. - Use

constfor all references; do not usevar. - If references need to be overridden, use

letinstead ofconst.

Template literals

You no longer need to do nested concatenation, you can use templates. Take a look:

ES5 var first = 'Adrian'; var last = 'Mejia'; console.log('Your name is ' + first + ' ' + last + '.'); Using backtick ( ) $ {} `can be done like this:

ES6 const first = 'Adrian'; const last = 'Mejia'; console.log(`Your name is ${first} ${last}.`); Multi-line strings

No more concatenation of strings with + \n :

ES5 var template = '<li *ngFor="let todo of todos" [ngClass]="{completed: todo.isDone}" >\n' + ' <div class="view">\n' + ' <input class="toggle" type="checkbox" [checked]="todo.isDone">\n' + ' <label></label>\n' + ' <button class="destroy"></button>\n' + ' </div>\n' + ' <input class="edit" value="">\n' + '</li>'; console.log(template); In ES6 you can reuse the backticks:

ES6 const template = `<li *ngFor="let todo of todos" [ngClass]="{completed: todo.isDone}" > <div class="view"> <input class="toggle" type="checkbox" [checked]="todo.isDone"> <label></label> <button class="destroy"></button> </div> <input class="edit" value=""> </li>`; console.log(template); Both code blocks generate the same result.

Destructuring Assignment

ES6 destructing is a useful and concise thing. Look at the examples:

Get item from array

ES5 var array = [1, 2, 3, 4]; var first = array[0]; var third = array[2]; console.log(first, third); // 1 3 Same:

ES6 const array = [1, 2, 3, 4]; const [first, ,third] = array; console.log(first, third); // 1 3 Value exchange

ES5 var a = 1; var b = 2; var tmp = a; a = b; b = tmp; console.log(a, b); // 2 1 Same:

ES6 let a = 1; let b = 2; [a, b] = [b, a]; console.log(a, b); // 2 1 Destructuring multiple return values

ES5 function margin() { var left=1, right=2, top=3, bottom=4; return { left: left, right: right, top: top, bottom: bottom }; } var data = margin(); var left = data.left; var bottom = data.bottom; console.log(left, bottom); // 1 4 Line 3 can be returned as an array:

return [left, right, top, bottom]; but the calling code will need to know about the order of the data.

var left = data[0]; var bottom = data[3]; With ES6, the caller selects only the required data (line 6):

ES6 function margin() { const left=1, right=2, top=3, bottom=4; return { left, right, top, bottom }; } const { left, bottom } = margin(); console.log(left, bottom); // 1 4 Note: Line 3 contains other features of ES6. You can abbreviate { left: left } to { left } . See how concise this is compared to ES5. Cool?

Destructuring and parameter mapping

ES5 var user = {firstName: 'Adrian', lastName: 'Mejia'}; function getFullName(user) { var firstName = user.firstName; var lastName = user.lastName; return firstName + ' ' + lastName; } console.log(getFullName(user)); // Adrian Mejia The same (but shorter):

ES6 const user = {firstName: 'Adrian', lastName: 'Mejia'}; function getFullName({ firstName, lastName }) { return `${firstName} ${lastName}`; } console.log(getFullName(user)); // Adrian Mejia Deep mapping

ES5 function settings() { return { display: { color: 'red' }, keyboard: { layout: 'querty'} }; } var tmp = settings(); var displayColor = tmp.display.color; var keyboardLayout = tmp.keyboard.layout; console.log(displayColor, keyboardLayout); // red querty The same (but shorter):

ES6 function settings() { return { display: { color: 'red' }, keyboard: { layout: 'querty'} }; } const { display: { color: displayColor }, keyboard: { layout: keyboardLayout }} = settings(); console.log(displayColor, keyboardLayout); // red querty This is also called object destructuring.

As you can see, destructurization can be very useful and can push to improve the coding style.

Tips:

- Use destructuring to get elements from an array and exchange values. No need to make temporary references - save time.

- Do not use array restructuring for multiple return values; instead, use object restructuring.

Classes and objects

In ECMAScript 6, we have moved from “constructor functions” to “classes”.

Each object in JavaScript has a prototype, which is a different object. All objects in JavaScript inherit methods and properties from their prototype.

In ES5, object-oriented programming was achieved using constructor functions. They created objects as follows:

ES5 var Animal = (function () { function MyConstructor(name) { this.name = name; } MyConstructor.prototype.speak = function speak() { console.log(this.name + ' makes a noise.'); }; return MyConstructor; })(); var animal = new Animal('animal'); animal.speak(); // animal makes a noise. In ES6 there is a new syntactic sugar. You can do the same thing with less code and using the class and construtor . Also note how clearly the methods are defined: construtor.prototype.speak = function () vs speak() :

ES6 class Animal { constructor(name) { this.name = name; } speak() { console.log(this.name + ' makes a noise.'); } } const animal = new Animal('animal'); animal.speak(); // animal makes a noise. Both styles (ES5 / 6) give the same result.

Tips:

- Always use

classsyntax and do not modifyprototypedirectly. The code will be more concise and easier to understand. - Avoid creating an empty constructor. Classes have a default constructor if you do not set your own.

Inheritance

Let's continue the previous example with the Animal class. Suppose we need a new class Lion .

In ES5, you will have to do a bit of work with prototype inheritance.

ES5 var Lion = (function () { function MyConstructor(name){ Animal.call(this, name); } // prototypal inheritance MyConstructor.prototype = Object.create(Animal.prototype); MyConstructor.prototype.constructor = Animal; MyConstructor.prototype.speak = function speak() { Animal.prototype.speak.call(this); console.log(this.name + ' roars '); }; return MyConstructor; })(); var lion = new Lion('Simba'); lion.speak(); // Simba makes a noise. // Simba roars. We will not go into details, but note a few details:

- Line 3, directly call the

Animalconstructor with parameters. - Lines 7-8, assign the

Lionprototype to theAnimalclass prototype. - Line 11, call the method

speakfrom the parent classAnimal.

In ES6 there are new keywords extends and super .

ES6 class Lion extends Animal { speak() { super.speak(); console.log(this.name + ' roars '); } } const lion = new Lion('Simba'); lion.speak(); // Simba makes a noise. // Simba roars. See how much better the code looks on ES6 compared to ES5. And they do the same thing! Win!

Tip:

- Use the built-in inheritance method.

Native promises

Moving from callback hell to promises

ES5 function printAfterTimeout(string, timeout, done){ setTimeout(function(){ done(string); }, timeout); } printAfterTimeout('Hello ', 2e3, function(result){ console.log(result); // nested callback printAfterTimeout(result + 'Reader', 2e3, function(result){ console.log(result); }); }); One function accepts a callback to start it upon completion. We need to run it twice, one after another. Therefore, you have to call printAfterTimeout a second time in the callback.

Everything gets really bad when you need to add a third or fourth callback. Let's see what can be done with promises:

ES6 function printAfterTimeout(string, timeout){ return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { setTimeout(function(){ resolve(string); }, timeout); }); } printAfterTimeout('Hello ', 2e3).then((result) => { console.log(result); return printAfterTimeout(result + 'Reader', 2e3); }).then((result) => { console.log(result); }); With then you can do without nested functions.

Arrow functions

In ES5, the usual definitions of the functions did not disappear, but a new format was added — the arrow functions.

ES5 has problems with this :

ES5 var _this = this; // need to hold a reference $('.btn').click(function(event){ _this.sendData(); // reference outer this }); $('.input').on('change',function(event){ this.sendData(); // reference outer this }.bind(this)); // bind to outer this You need to use a temporary this to refer to it inside a function or use bind . In ES6, you can simply use the arrow function!

ES6 // this will reference the outer one $('.btn').click((event) => this.sendData()); // implicit returns const ids = [291, 288, 984]; const messages = ids.map(value => `ID is ${value}`); For ... of

From for go to forEach and then to for...of :

ES5 // for var array = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']; for (var i = 0; i < array.length; i++) { var element = array[i]; console.log(element); } // forEach array.forEach(function (element) { console.log(element); }); ES6 for ... of allows you to use iterators

ES6 // for ...of const array = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']; for (const element of array) { console.log(element); } Default settings

From checking the parameters go to the default settings. Have you done anything like this before?

ES5 function point(x, y, isFlag){ x = x || 0; y = y || -1; isFlag = isFlag || true; console.log(x,y, isFlag); } point(0, 0) // 0 -1 true point(0, 0, false) // 0 -1 true point(1) // 1 -1 true point() // 0 -1 true Probably yes. This is a common pattern for checking the value of a variable. But there are some problems:

- Line 8, pass

0, 0get0, -1 - Line 9, pass

false, but we gettrue.

If the default parameter is a boolean variable or if you set the value to 0, then nothing happens. Why? I will tell after this example with ES6;)

In ES6, everything works better with less code:

ES6 function point(x = 0, y = -1, isFlag = true){ console.log(x,y, isFlag); } point(0, 0) // 0 0 true point(0, 0, false) // 0 0 false point(1) // 1 -1 true point() // 0 -1 true We get the expected result. The example in ES5 did not work. You need to check for undefined since false , null , undefined and 0 are all falsy values. With numbers, you can:

ES5 function point(x, y, isFlag){ x = x || 0; y = typeof(y) === 'undefined' ? -1 : y; isFlag = typeof(isFlag) === 'undefined' ? true : isFlag; console.log(x,y, isFlag); } point(0, 0) // 0 0 true point(0, 0, false) // 0 0 false point(1) // 1 -1 true point() // 0 -1 true With the check for undefined everything works as it should.

Rest parameters

From arguments to rest parameters and spread operation.

In ES5, working with a variable number of arguments is inconvenient.

ES5 function printf(format) { var params = [].slice.call(arguments, 1); console.log('params: ', params); console.log('format: ', format); } printf('%s %d %.2f', 'adrian', 321, Math.PI); With rest ... everything is much simpler.

ES6 function printf(format, ...params) { console.log('params: ', params); console.log('format: ', format); } printf('%s %d %.2f', 'adrian', 321, Math.PI); Spread operation

Moving from apply() to spread. Again, ... to the rescue:

Remember: we useapply()to turn an array into an argument list. for example,Math.max()takes a list of parameters, but if we have an array, we can useapply.

ES5 Math.max.apply(Math, [2,100,1,6,43]) // 100 In ES6 we use spread:

ES6 Math.max(...[2,100,1,6,43]) // 100 We also moved from concat to spread'u:

ES5 var array1 = [2,100,1,6,43]; var array2 = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']; var array3 = [false, true, null, undefined]; console.log(array1.concat(array2, array3)); In ES6:

ES6 const array1 = [2,100,1,6,43]; const array2 = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']; const array3 = [false, true, null, undefined]; console.log([...array1, ...array2, ...array3]); Conclusion

JavaScript has changed a lot. This article covers only the basic features that every developer should know about.

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/313526/

All Articles