Donald Knut: how I started analyzing algorithms and went to the USSR for this (37.91.97 / 97)

“Andrei (Ershov), imagine how great it would be to organize something like a pilgrimage, where programmers from all over the world could come to Khorezm and celebrate the birth of this concept.”

- Donald Knut persuades Yershov to organize an international symposium

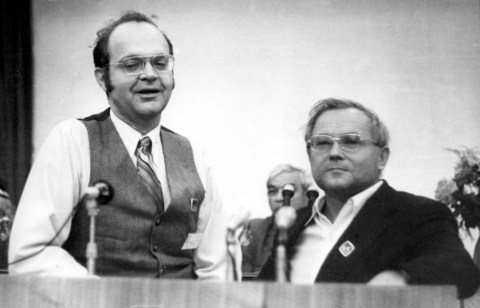

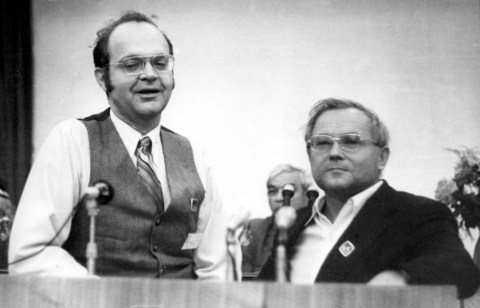

Knut and Ershov

Knut and Ershov

In the fall of 1967 there was a conference of mathematicians in Santa Barbara, perhaps it was the same year when I also attended a conference in Chapel Hill. I met many people who stimulated me, and there were a lot of interesting problems that we had to discuss with each other. But when I got to the Santa Barbara conference, I realized that this was my only chance to do research. I did not attend lectures. I just sat on the beach and wrote my article about attribute grammar right during the conference. But I attended dinners. I remember someone asking me what I was doing and I decided to be a programmer, not a mathematician at that moment.

')

- I think I'm going to be a programmer.

- Oh, so you are doing a numerical analysis?

- Not really.

- Ahhh, artificial intelligence.

- No, not artificial intelligence.

- Then you must be doing programming languages?

In other words, I was eventually asked to write a book about the compiler. In fact, at that time it was believed that programming consists of three parts: numerical analysis, artificial intelligence, and programming languages. Stanford faculty was also kind of divided into three main blocks. They had three qualified exams and the like. But I said, "You know, I did a lot of research in the field of programming languages, I was the editor of the journal on programming languages, but my main interest is a bit different." And then I realized that there is no name for what interests me the most. And how to call it?

By that time, I had already written 3,000 pages of the Art of Programming, printed some of them and was almost ready to publish them. And it turned out that we needed a mathematical basis for understanding the quality of computer methods. You wanted to know how good the method is, if it can be twice as good as the other, etc. It was necessary to say not just “yes, better,” but to explain how much better and why. Therefore, I decided to make this the main theme that unites my books, to find ways to assess computer value. But I did not have a name for it.

At a conference in Santa Barbara, I realized that if I was going to explain to someone in what field I was working, I should have a name for it. Therefore, I decided to call it an analysis of algorithms. I am writing a book and I can explain to people what this means. I talked to my publisher and said “Let's change the title of the book, let's call it“ Analysis of Algorithms ”.”

This idea was not approved, but in any case I decided that this would be my career, that I would concentrate mainly on the analysis of algorithms. This means that I will determine how good this or that algorithm or computer method is.

I was once asked to give a lecture at the international information processing congress in 1971. I titled the lecture as “Analysis of Algorithms”. I was also asked to give a speech at the International Mathematical Conference in France in 1970 and I titled it as “Mathematical Analysis of Algorithms”. I tried to promote this term so that people understand what I do. And I am pleased to report that after 10 years or so, in the late 70s, columns in magazines began to appear and books called Analysis of Algorithms began to appear.

In fact, despite the fact that my publishers did not like this title, quite a few books have a similar title. But I had to somehow name the area in which I work. If someone asked me to explain what it really means, I would say that this is just what I'm interested in.

I said that I wanted algorithm analysis to be the work of my life. Most of my work, including writing The Art of Programming, was to find a way to determine how good the algorithm was. I liked the study of algorithms the most, and always was in the first place for me.

I was pleased to learn that the word "algorithm" comes from the Arabic Al-Khorezmi. Now Khorezm is a region in Uzbekistan, but then it was a lake. I mean the Aral Sea, which used to be called Lake Khorezmi. This is the part of the world that is completely forgotten.

If you look at the map of Iran, then this place is located to the north, if you look at the map of Romania, then to the east, if you look at the map of India or Afghanistan, then to the west, south of Russia, do you understand? This part of the world is simply forgotten. But I found out that the word "algorithm" came from there, Khorezm. You know, there are places where Armenians live and they call it the Armenian diaspora? There is a whole Khorezm quarter in Baghdad. And I thought, okay, it would be interesting to visit Khorezm once. I looked at the atlas and was horrified. It's in the very heart of the USSR, how can I even get there?!? There are no roads that would lead directly to this place.

I told this to my friend Andrei Yershov, who came from Russia, from the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Well, he wasn't my friend at the time, I didn't know him very well, but he was a friend of John McCarthy and we were at a party at his house. I told Andrei: “Do you know that the word“ algorithm ”comes from a place that is in the Soviet Union? We should note this somehow. Imagine how great it would be to organize something like a pilgrimage, where programmers from all over the world could come to Khorezm and celebrate the birth of this concept. ”

And he said: "Sounds like a great idea!". He returned home and began work on organizing all of this. He asked the Soviet Academy of Sciences to sponsor an international symposium on algorithms that would last two weeks and take place in the Khorezm region.

Even before I got to Khorezm, when I first got off the plane, I was greeted by 200 children who were carrying flowers, and then I was interviewed for local television. This was the first time that anyone had shown such an interest in their lands. The hospitality of the people in the Middle East is amazing. In fact, you know, the hosts were so generous that I jokingly asked them to give me a kept woman. And I am sure that they would have done so if I had not assured them that I was just joking. We could visit a peculiar city-museum of Khiva, from where the creator of the algorithm Al-Khorezmi was probably born.

I'm not sure, but in any case it is a kind of preserved city that shows the great wealth of this culture. Half of the people at this conference were from the USSR and the other half from different parts of the world. We could just discuss the significance of the algorithms. The opportunity to arrange this small meeting and see this corner of the world was one of the greatest achievements in my life.

D. Knut is dancing

Surprisingly, we met in this village children of different nationalities: blond, blue-eyed, some with Korean ancestry. We visited cotton farms and collected cotton. I got a hat in which people go to Khorezm. So now, when I work on algorithms, I can be appropriately dressed.

For each written work, and I wrote a lot of them, there is some interesting story. The algorithm itself became famous, but I myself have not used it for the past 20 years. However, it is in all textbooks and is an instructive example.

For example, it is good to use when you try to look at a long passage from the text to find a specific word. Suppose I am looking for the word (or article in English) or something like that. Although it would be foolish to search for this word, let's search for dikran (* plant dicran).

Obviously, you stop at every place in the text and ask yourself, “Is this the letter D? Fine. Next is the letter I? Good. Further K? No, this word is 'direction' (* distance from English). Then you move on and repeat this algorithm from the beginning. Is it d? No, we have already found out that this is I. It means that we need to move further. But everything is not so simple. There are more difficult words. If we were looking for the word 'didymus' (* twin with English), where there are two letters D, then our algorithm would no longer work.

A professor at Berkeley, Steve Cook, has an amazing theorem on this. He argues that if we took a computer that is very limited in its capabilities and if we could write a program that would solve the problem, for this stupid computer no matter how slow this program would work, then there is a quick way to write the same program for a normal computer.

In other words, we take a certain computer with limited capabilities and if the problem can be solved on it, then there is a quick way to do it on a normal computer. The only problem that would be worth solving with this computer is the ability to determine if the set of letters is a palindrome and to rotate the same in the chain of palindromes.

I was just curious. In fact, no one is interested in the concatenation of palindromes. According to the theorem of Cook, if there is a way to solve this problem on this funny computer, then there is a quick way to recognize these connections of palindromes on a regular computer. But I could not think of any good way to do it on a normal computer, it seemed to me that it would be much more difficult.

I was a pretty good programmer, but this theorem claimed that there was a way to do it, but I could not think of how. For the first time I was in such a kind of impasse and could not stop thinking about it. I spent the day and evening to detail on the board the theory of Cook and finally find a quick way to bring this to life on the computer.

Suddenly I found a clue. Initially, the idea was to write a program that would reflect this general theorem, but it could also solve the problem of searching in the text. I mentioned this on a trip to Berkeley and met Vaughan Pratt there. He was the one who made the greatest contribution, I just was the one who wrote it down afterwards.

Then we learned that the same idea was visited by Jim Morris a couple of months earlier, but people looked at his program, did not understand it and therefore did not take it. In any case, I believe that this is an effective way to search the text, which also gives a good idea of the basics of computer science. This method has become famous and is associated with my name.

As I have already said, I wrote 160 papers and for each of them there is some interesting story.

Translation: Diana Sheremyeva

A. P. Ershov among the leaders of the republican party and Soviet bodies of Uzbekistan in the cotton field.

The article "Scientific pilgrimage to the homeland of Al-Khorezmi"

Preface (written jointly by AP Ershov and D. Knut; translated into Russian by A. P. Ershov.)

The article by Donald Knuth "Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computational Science" , translated into Russian by G.S. Zeitin.

Materials from the archive of Ershov: International Symposium "Algorithm in Modern Mathematics and its Applications"

Publishing support - Edison , which develops crowdsourcing platforms for product promotion and writes designs for an interactive real estate database .

- Donald Knut persuades Yershov to organize an international symposium

In the fall of 1967 there was a conference of mathematicians in Santa Barbara, perhaps it was the same year when I also attended a conference in Chapel Hill. I met many people who stimulated me, and there were a lot of interesting problems that we had to discuss with each other. But when I got to the Santa Barbara conference, I realized that this was my only chance to do research. I did not attend lectures. I just sat on the beach and wrote my article about attribute grammar right during the conference. But I attended dinners. I remember someone asking me what I was doing and I decided to be a programmer, not a mathematician at that moment.

')

- I think I'm going to be a programmer.

- Oh, so you are doing a numerical analysis?

- Not really.

- Ahhh, artificial intelligence.

- No, not artificial intelligence.

- Then you must be doing programming languages?

New area - analysis of algorithms

In other words, I was eventually asked to write a book about the compiler. In fact, at that time it was believed that programming consists of three parts: numerical analysis, artificial intelligence, and programming languages. Stanford faculty was also kind of divided into three main blocks. They had three qualified exams and the like. But I said, "You know, I did a lot of research in the field of programming languages, I was the editor of the journal on programming languages, but my main interest is a bit different." And then I realized that there is no name for what interests me the most. And how to call it?

By that time, I had already written 3,000 pages of the Art of Programming, printed some of them and was almost ready to publish them. And it turned out that we needed a mathematical basis for understanding the quality of computer methods. You wanted to know how good the method is, if it can be twice as good as the other, etc. It was necessary to say not just “yes, better,” but to explain how much better and why. Therefore, I decided to make this the main theme that unites my books, to find ways to assess computer value. But I did not have a name for it.

At a conference in Santa Barbara, I realized that if I was going to explain to someone in what field I was working, I should have a name for it. Therefore, I decided to call it an analysis of algorithms. I am writing a book and I can explain to people what this means. I talked to my publisher and said “Let's change the title of the book, let's call it“ Analysis of Algorithms ”.”

This idea was not approved, but in any case I decided that this would be my career, that I would concentrate mainly on the analysis of algorithms. This means that I will determine how good this or that algorithm or computer method is.

I was once asked to give a lecture at the international information processing congress in 1971. I titled the lecture as “Analysis of Algorithms”. I was also asked to give a speech at the International Mathematical Conference in France in 1970 and I titled it as “Mathematical Analysis of Algorithms”. I tried to promote this term so that people understand what I do. And I am pleased to report that after 10 years or so, in the late 70s, columns in magazines began to appear and books called Analysis of Algorithms began to appear.

In fact, despite the fact that my publishers did not like this title, quite a few books have a similar title. But I had to somehow name the area in which I work. If someone asked me to explain what it really means, I would say that this is just what I'm interested in.

International Symposium on Algorithms in the USSR

I said that I wanted algorithm analysis to be the work of my life. Most of my work, including writing The Art of Programming, was to find a way to determine how good the algorithm was. I liked the study of algorithms the most, and always was in the first place for me.

I was pleased to learn that the word "algorithm" comes from the Arabic Al-Khorezmi. Now Khorezm is a region in Uzbekistan, but then it was a lake. I mean the Aral Sea, which used to be called Lake Khorezmi. This is the part of the world that is completely forgotten.

If you look at the map of Iran, then this place is located to the north, if you look at the map of Romania, then to the east, if you look at the map of India or Afghanistan, then to the west, south of Russia, do you understand? This part of the world is simply forgotten. But I found out that the word "algorithm" came from there, Khorezm. You know, there are places where Armenians live and they call it the Armenian diaspora? There is a whole Khorezm quarter in Baghdad. And I thought, okay, it would be interesting to visit Khorezm once. I looked at the atlas and was horrified. It's in the very heart of the USSR, how can I even get there?!? There are no roads that would lead directly to this place.

I told this to my friend Andrei Yershov, who came from Russia, from the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Well, he wasn't my friend at the time, I didn't know him very well, but he was a friend of John McCarthy and we were at a party at his house. I told Andrei: “Do you know that the word“ algorithm ”comes from a place that is in the Soviet Union? We should note this somehow. Imagine how great it would be to organize something like a pilgrimage, where programmers from all over the world could come to Khorezm and celebrate the birth of this concept. ”

And he said: "Sounds like a great idea!". He returned home and began work on organizing all of this. He asked the Soviet Academy of Sciences to sponsor an international symposium on algorithms that would last two weeks and take place in the Khorezm region.

Even before I got to Khorezm, when I first got off the plane, I was greeted by 200 children who were carrying flowers, and then I was interviewed for local television. This was the first time that anyone had shown such an interest in their lands. The hospitality of the people in the Middle East is amazing. In fact, you know, the hosts were so generous that I jokingly asked them to give me a kept woman. And I am sure that they would have done so if I had not assured them that I was just joking. We could visit a peculiar city-museum of Khiva, from where the creator of the algorithm Al-Khorezmi was probably born.

I'm not sure, but in any case it is a kind of preserved city that shows the great wealth of this culture. Half of the people at this conference were from the USSR and the other half from different parts of the world. We could just discuss the significance of the algorithms. The opportunity to arrange this small meeting and see this corner of the world was one of the greatest achievements in my life.

D. Knut is dancing

Surprisingly, we met in this village children of different nationalities: blond, blue-eyed, some with Korean ancestry. We visited cotton farms and collected cotton. I got a hat in which people go to Khorezm. So now, when I work on algorithms, I can be appropriately dressed.

Why I chose algorithm analysis as a field of study.

For each written work, and I wrote a lot of them, there is some interesting story. The algorithm itself became famous, but I myself have not used it for the past 20 years. However, it is in all textbooks and is an instructive example.

For example, it is good to use when you try to look at a long passage from the text to find a specific word. Suppose I am looking for the word (or article in English) or something like that. Although it would be foolish to search for this word, let's search for dikran (* plant dicran).

Obviously, you stop at every place in the text and ask yourself, “Is this the letter D? Fine. Next is the letter I? Good. Further K? No, this word is 'direction' (* distance from English). Then you move on and repeat this algorithm from the beginning. Is it d? No, we have already found out that this is I. It means that we need to move further. But everything is not so simple. There are more difficult words. If we were looking for the word 'didymus' (* twin with English), where there are two letters D, then our algorithm would no longer work.

A professor at Berkeley, Steve Cook, has an amazing theorem on this. He argues that if we took a computer that is very limited in its capabilities and if we could write a program that would solve the problem, for this stupid computer no matter how slow this program would work, then there is a quick way to write the same program for a normal computer.

In other words, we take a certain computer with limited capabilities and if the problem can be solved on it, then there is a quick way to do it on a normal computer. The only problem that would be worth solving with this computer is the ability to determine if the set of letters is a palindrome and to rotate the same in the chain of palindromes.

I was just curious. In fact, no one is interested in the concatenation of palindromes. According to the theorem of Cook, if there is a way to solve this problem on this funny computer, then there is a quick way to recognize these connections of palindromes on a regular computer. But I could not think of any good way to do it on a normal computer, it seemed to me that it would be much more difficult.

I was a pretty good programmer, but this theorem claimed that there was a way to do it, but I could not think of how. For the first time I was in such a kind of impasse and could not stop thinking about it. I spent the day and evening to detail on the board the theory of Cook and finally find a quick way to bring this to life on the computer.

Suddenly I found a clue. Initially, the idea was to write a program that would reflect this general theorem, but it could also solve the problem of searching in the text. I mentioned this on a trip to Berkeley and met Vaughan Pratt there. He was the one who made the greatest contribution, I just was the one who wrote it down afterwards.

Then we learned that the same idea was visited by Jim Morris a couple of months earlier, but people looked at his program, did not understand it and therefore did not take it. In any case, I believe that this is an effective way to search the text, which also gives a good idea of the basics of computer science. This method has become famous and is associated with my name.

As I have already said, I wrote 160 papers and for each of them there is some interesting story.

Translation: Diana Sheremyeva

A. P. Ershov among the leaders of the republican party and Soviet bodies of Uzbekistan in the cotton field.

Ershov invites to the Dijkstra Symposium

Abstracts of the Knut Report at the symposium

The article "Scientific pilgrimage to the homeland of Al-Khorezmi"

Preface (written jointly by AP Ershov and D. Knut; translated into Russian by A. P. Ershov.)

The article by Donald Knuth "Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computational Science" , translated into Russian by G.S. Zeitin.

Photos from the symposium

Materials from the archive of Ershov: International Symposium "Algorithm in Modern Mathematics and its Applications"

Read more

- Donald Knut: I sat in the back row and hunted jokes, and the teachers resigned and didn't often beat on the ass (1,2,3,7 / 97)

- Donald Knut: “My advice to the young” (93/97) and “Feeling the need to assert oneself” (9/97)

- Surreal Numbers: I worked for six days, and rested on the seventh (40,41,42 / 97)

- Donald Knut: How the “Art of Programming” was created (33,38,39 / 97)

- Social Architecture: stratagems for success in open source projects

List of 97 videos with stories of Donald Knut

Youtube playlist

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

Publishing support - Edison , which develops crowdsourcing platforms for product promotion and writes designs for an interactive real estate database .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/313306/

All Articles