Donald Knut: about his wife, kisses, "Concrete math" and a look at teaching at the university

“We have a Californian book about mathematics. A book that showed the informal style of classes at Stanford, along with what I consider to be the personal manifesto of the way of doing mathematics. ”

- Donald Knut

“At the time, there was a lot of confusion. Some people complained that mathematics is becoming too abstract, that it is too divorced from reality, so I could joke around a bit by calling the course “concrete mathematics”. Although I said that the word “concrete” is not actually the antonym of the abstract, it is a combination of the word continuous and discrete (CONtinuous and disCRETE). ”

- Donald Knut

')

“I always conducted my classes, almost as if it was a language lesson, not computer science or mathematics, I addressed the question to the students and they had to figure out how to solve this problem or at least take the next step towards solving the problem , or try and fail, and then we learned how to fix it. You know, you will not find books that describe how to recover from unsuccessful assumptions. And so we could learn how to do this in the classroom. ”

In the student fraternity, I had a best friend who was also in the honor section of the Sase, his name was Bill Davis. He is now a professor of mathematics in Ohio and is very active in the field of online learning of mathematics. Bill and I were bosom buddies during my first school year. In the second year of study, we both entered into the Theta Chi fraternity, then we went through hellish week together and our rooms were next door to the fraternity house.

I started dating a girl from Western Reserve University, her name was Betsy, and her roommate was Jill. Bill met with Jill. Betsy was a Catholic, and I was a Lutheran, and that was something that we thought our families could never understand. And although I still thought Betsy was pretty attractive, I also met a girl named Becky, a Jewish girl whose father owned a store in Cleveland and I met several nurses too, you know ...

There were many girls who spent time around Case. But I was interested in Betsy, and I decided that we would have a double date with Bill Davis and his girlfriend Jill. And as I said, Betsy and Jill were roommates, Bill and I were roommates. I wondered if our relationship with Betsy could grow into something more. I decided to have lunch with Jill to ask her advice. It was in my second year of study ... in the spring of my second year of study. She was such a good listener and gave such good advice that I started dating Jill instead of Betsy.

I'm not sure that Bill forgave me for this, but she didn’t like him very much, as she said. Well, in any case, Jill was the one with whom I ended up in a relationship, to whom I made offers and to whom I married and now we have been married for 45 years.

Jill and I started dating in the library where we were studying together. With her, I first started enjoying kisses. In high school, I was afraid to kiss girls, even when they got up. I mean, I met a girl in high school, which was about four and a half feet, I don’t remember her name already, but I remember that she was really sweet. I always liked short girls, because it seemed that they had a good balance, that they didn’t fall as easily as they did tall ones. I was tall. She was a cheerleader, and she was standing on the porch of her house, and her lips were raised up, and I realized that I should kiss her, but I had never done this before. How will I do it, you understand? And in the end, I kissed her, but I never, never realized how beautiful it was, until in my second year I kissed Jill.

Now I am retired, but I still cannot devote all my time to the work on “The Art of Programming”, because there are other projects that I really have to finish. For example, I told you about the book “3:16,” which I wrote on the weekend, I would like to finish it. It was just at the end of the 80s. It was published, I think, in early 1990. Then I introduced a subject at Stanford called "Specific Mathematics".

I started it in 1970, maybe in 1971, but probably in the 70th ... well, it could have been in the fall of the 70th or in the spring of the 71st. In any case, it was a completely new course in the curriculum. Students at Stanford did not have the opportunity to study the type of mathematics that I considered necessary for work in the field of computer science. When I wrote the first parts of “The Art of Programming,” I thought a lot about what I needed from what I had never been taught at school.

And at the time there was a lot of confusion. Some people complained that mathematics is becoming too abstract, that it is too divorced from reality, so I could joke a little by calling the course “concrete mathematics”. Although I said that the word “concrete” is not actually the antonym of the abstract, it is a combination of the word continuous and discrete (CONtinuous and disCRETE).

We had this course - “Concrete Mathematics” - the students were delighted, and I conducted it again and again. Sometimes we had guest lectures. When I took a sabbatical or when I could not give a lecture, I was replaced by another teacher who conducted the subject according to the established model. And one of the methods that I always used when teaching at Stanford, which Georg Poya inspired me to use, was to allow students to talk in class instead of telling them what was written in the book. I assumed that they all know how to read and therefore, when they are in class we will talk, we will do tasks that are not in the book.

So I always conducted my classes, almost as if it was a language lesson, not computer science or mathematics, I addressed the question to the students and they had to figure out how to solve this problem or at least take the next step towards solving the problem , or try and fail, and then we learned how to fix it.

You know, you will not find books that describe how to recover from unsuccessful assumptions. And so we could learn how to do this in the classroom. So that the students did not need to write notes in the class, my assistants always recorded what the students said, and then without delay they published these notes and obtained a sort of transcript of the session.

So, by the 1990s, I had almost 20 years of these transcripts of classroom conversations that we had with students in the course on “concrete mathematics”. And it was natural, almost obligatory, that this legacy would be passed on to the next generations, and therefore I wanted to write a book “concrete mathematics”, in which it would be described how the course developed and what was studied.

One of the most conscientious assistants - Oren Patashnik - not only recorded the sessions in the classes, but then made a plan, I think, almost all the chapters of the book as handouts for students so that they could use it in one of those years when I did not teach.

And I could build on his notes and rewrite them using his understanding of pedagogy when I was writing this book.

Ron graham

And Ron Graham was the most successful teacher on the course in my absence. He replaced me 2 or 3 times, the students loved him so much that every year they organized group meetings of the “concrete mathematics” class. And then he also began teaching at Princeton. And I got this book "concrete math" with two co-authors: Oren Patashnik and Ron Graham. Usually when I create a book I write one page per day. I mean, if a book consists of 365 pages, then I will write it for a year. If it has 500 pages, then I will write it for a year and a half. In this case, I overdid it and got 600 ready-made pages of the book in a little less than one year.

Oren Patashnik

It was not a viable working style, but I wanted so much to go back to working on The Art of Computer Programming that Jill gave me a year when I shouldn’t have to be a reliable husband, when I could be less a person so that I can finish this project and then I would fill this time.

In any case, it was a shock project, the work on which was conducted with tension, but I had an incentive in the form of excellent mathematical material that came out of my pen and I had a draft by Oren Patashnik, who could, you know, could do this Californian book. One of the funniest things in the book "Concrete Mathematics" was ... I borrowed it from Stanford.

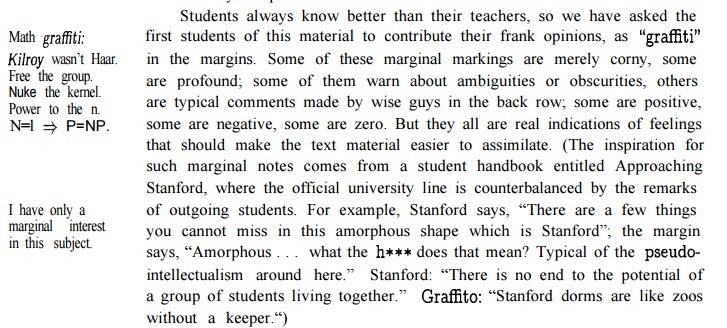

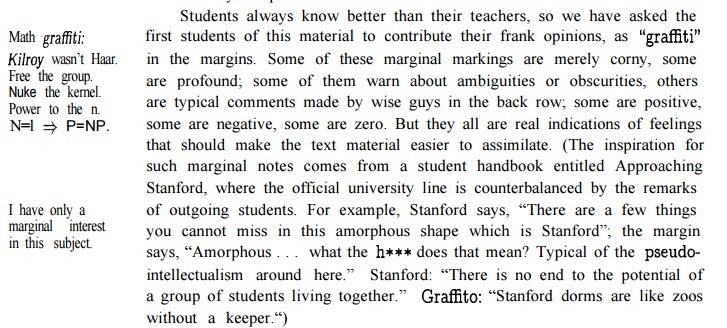

In the early 1970s, Stanford University had a truly innovative idea for prospective students. They released a book called Approaching Stanford, which was written by former students. In the main part of the book you could find, what is expected from the university book, information about what a great place it is, what the weather is like here, what big faculties, what excellent students and so on.

And on the fields were graffiti, where students wrote how everything is in fact. For example, that the Stanford hostels are like a zoo without a caretaker and so on. And they posted these realistic notes about what kind of life at Stanford written by the students themselves. And Stanford printed the book and sent it to prospective students. And I thought, but let's do it with a book on mathematics. Let's post graffiti in a math textbook, let's give students the opportunity to comment on what they think about the subject and you know, it turned out that this idea undoubtedly stuck because the book is a specific math ...

Let me first notice if someone finds a mistake in any of my books, I give them back money. Yes, you know, if they are the first to notice a mistake, then I send them a check. And any errors in these graffiti were identified immediately, it was clear that all readers also read graffiti. Mistakes in other parts of the book, you know, could have passed three or four years before someone finds them. But if there was anything that they could comment on in the graffiti section, it was done.

The book was also translated into 10 languages, and in almost all cases a graffiti translation was made, the translators believed that this was an essential part of the book. And so the book is not presented as something serious, although it is.

It also turned out to be one of their ways to contribute to the book’s content because, for example, one of the comments suggested skipping the next few pages, because you don’t want to bother so much until you come across this.

And there were others, some beaten jokes that we censored a little. And we published a Californian book about mathematics. A book that showed the informal style of classes at Stanford, along with what I consider to be the personal manifesto of the way mathematics is the way I think I like working with the type of mathematics I need to study computer programs at any level.

Publishing support is Edison , which has developed hundreds of site parsers and a service for sending push notifications to the bank .

- Donald Knut

“At the time, there was a lot of confusion. Some people complained that mathematics is becoming too abstract, that it is too divorced from reality, so I could joke around a bit by calling the course “concrete mathematics”. Although I said that the word “concrete” is not actually the antonym of the abstract, it is a combination of the word continuous and discrete (CONtinuous and disCRETE). ”

- Donald Knut

')

“I always conducted my classes, almost as if it was a language lesson, not computer science or mathematics, I addressed the question to the students and they had to figure out how to solve this problem or at least take the next step towards solving the problem , or try and fail, and then we learned how to fix it. You know, you will not find books that describe how to recover from unsuccessful assumptions. And so we could learn how to do this in the classroom. ”

Meeting my wife jill

In the student fraternity, I had a best friend who was also in the honor section of the Sase, his name was Bill Davis. He is now a professor of mathematics in Ohio and is very active in the field of online learning of mathematics. Bill and I were bosom buddies during my first school year. In the second year of study, we both entered into the Theta Chi fraternity, then we went through hellish week together and our rooms were next door to the fraternity house.

I started dating a girl from Western Reserve University, her name was Betsy, and her roommate was Jill. Bill met with Jill. Betsy was a Catholic, and I was a Lutheran, and that was something that we thought our families could never understand. And although I still thought Betsy was pretty attractive, I also met a girl named Becky, a Jewish girl whose father owned a store in Cleveland and I met several nurses too, you know ...

There were many girls who spent time around Case. But I was interested in Betsy, and I decided that we would have a double date with Bill Davis and his girlfriend Jill. And as I said, Betsy and Jill were roommates, Bill and I were roommates. I wondered if our relationship with Betsy could grow into something more. I decided to have lunch with Jill to ask her advice. It was in my second year of study ... in the spring of my second year of study. She was such a good listener and gave such good advice that I started dating Jill instead of Betsy.

I'm not sure that Bill forgave me for this, but she didn’t like him very much, as she said. Well, in any case, Jill was the one with whom I ended up in a relationship, to whom I made offers and to whom I married and now we have been married for 45 years.

Jill and I started dating in the library where we were studying together. With her, I first started enjoying kisses. In high school, I was afraid to kiss girls, even when they got up. I mean, I met a girl in high school, which was about four and a half feet, I don’t remember her name already, but I remember that she was really sweet. I always liked short girls, because it seemed that they had a good balance, that they didn’t fall as easily as they did tall ones. I was tall. She was a cheerleader, and she was standing on the porch of her house, and her lips were raised up, and I realized that I should kiss her, but I had never done this before. How will I do it, you understand? And in the end, I kissed her, but I never, never realized how beautiful it was, until in my second year I kissed Jill.

My class on "Concrete Mathematics"

Now I am retired, but I still cannot devote all my time to the work on “The Art of Programming”, because there are other projects that I really have to finish. For example, I told you about the book “3:16,” which I wrote on the weekend, I would like to finish it. It was just at the end of the 80s. It was published, I think, in early 1990. Then I introduced a subject at Stanford called "Specific Mathematics".

I started it in 1970, maybe in 1971, but probably in the 70th ... well, it could have been in the fall of the 70th or in the spring of the 71st. In any case, it was a completely new course in the curriculum. Students at Stanford did not have the opportunity to study the type of mathematics that I considered necessary for work in the field of computer science. When I wrote the first parts of “The Art of Programming,” I thought a lot about what I needed from what I had never been taught at school.

And at the time there was a lot of confusion. Some people complained that mathematics is becoming too abstract, that it is too divorced from reality, so I could joke a little by calling the course “concrete mathematics”. Although I said that the word “concrete” is not actually the antonym of the abstract, it is a combination of the word continuous and discrete (CONtinuous and disCRETE).

We had this course - “Concrete Mathematics” - the students were delighted, and I conducted it again and again. Sometimes we had guest lectures. When I took a sabbatical or when I could not give a lecture, I was replaced by another teacher who conducted the subject according to the established model. And one of the methods that I always used when teaching at Stanford, which Georg Poya inspired me to use, was to allow students to talk in class instead of telling them what was written in the book. I assumed that they all know how to read and therefore, when they are in class we will talk, we will do tasks that are not in the book.

So I always conducted my classes, almost as if it was a language lesson, not computer science or mathematics, I addressed the question to the students and they had to figure out how to solve this problem or at least take the next step towards solving the problem , or try and fail, and then we learned how to fix it.

You know, you will not find books that describe how to recover from unsuccessful assumptions. And so we could learn how to do this in the classroom. So that the students did not need to write notes in the class, my assistants always recorded what the students said, and then without delay they published these notes and obtained a sort of transcript of the session.

Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

So, by the 1990s, I had almost 20 years of these transcripts of classroom conversations that we had with students in the course on “concrete mathematics”. And it was natural, almost obligatory, that this legacy would be passed on to the next generations, and therefore I wanted to write a book “concrete mathematics”, in which it would be described how the course developed and what was studied.

One of the most conscientious assistants - Oren Patashnik - not only recorded the sessions in the classes, but then made a plan, I think, almost all the chapters of the book as handouts for students so that they could use it in one of those years when I did not teach.

And I could build on his notes and rewrite them using his understanding of pedagogy when I was writing this book.

Ron graham

And Ron Graham was the most successful teacher on the course in my absence. He replaced me 2 or 3 times, the students loved him so much that every year they organized group meetings of the “concrete mathematics” class. And then he also began teaching at Princeton. And I got this book "concrete math" with two co-authors: Oren Patashnik and Ron Graham. Usually when I create a book I write one page per day. I mean, if a book consists of 365 pages, then I will write it for a year. If it has 500 pages, then I will write it for a year and a half. In this case, I overdid it and got 600 ready-made pages of the book in a little less than one year.

Oren Patashnik

It was not a viable working style, but I wanted so much to go back to working on The Art of Computer Programming that Jill gave me a year when I shouldn’t have to be a reliable husband, when I could be less a person so that I can finish this project and then I would fill this time.

In any case, it was a shock project, the work on which was conducted with tension, but I had an incentive in the form of excellent mathematical material that came out of my pen and I had a draft by Oren Patashnik, who could, you know, could do this Californian book. One of the funniest things in the book "Concrete Mathematics" was ... I borrowed it from Stanford.

In the early 1970s, Stanford University had a truly innovative idea for prospective students. They released a book called Approaching Stanford, which was written by former students. In the main part of the book you could find, what is expected from the university book, information about what a great place it is, what the weather is like here, what big faculties, what excellent students and so on.

And on the fields were graffiti, where students wrote how everything is in fact. For example, that the Stanford hostels are like a zoo without a caretaker and so on. And they posted these realistic notes about what kind of life at Stanford written by the students themselves. And Stanford printed the book and sent it to prospective students. And I thought, but let's do it with a book on mathematics. Let's post graffiti in a math textbook, let's give students the opportunity to comment on what they think about the subject and you know, it turned out that this idea undoubtedly stuck because the book is a specific math ...

Let me first notice if someone finds a mistake in any of my books, I give them back money. Yes, you know, if they are the first to notice a mistake, then I send them a check. And any errors in these graffiti were identified immediately, it was clear that all readers also read graffiti. Mistakes in other parts of the book, you know, could have passed three or four years before someone finds them. But if there was anything that they could comment on in the graffiti section, it was done.

The book was also translated into 10 languages, and in almost all cases a graffiti translation was made, the translators believed that this was an essential part of the book. And so the book is not presented as something serious, although it is.

It also turned out to be one of their ways to contribute to the book’s content because, for example, one of the comments suggested skipping the next few pages, because you don’t want to bother so much until you come across this.

And there were others, some beaten jokes that we censored a little. And we published a Californian book about mathematics. A book that showed the informal style of classes at Stanford, along with what I consider to be the personal manifesto of the way mathematics is the way I think I like working with the type of mathematics I need to study computer programs at any level.

Read more

- Donald Knut: I sat in the back row and hunted jokes, and the teachers resigned and didn't often beat on the ass (1,2,3,7 / 97)

- Donald Knut: “My advice to the young” (93/97) and “Feeling the need to assert oneself” (9/97)

- Surreal Numbers: I worked for six days, and rested on the seventh (40,41,42 / 97)

- Donald Knut: How the “Art of Programming” was created (33,38,39 / 97)

- Social Architecture: stratagems for success in open source projects

List of 97 videos with stories of Donald Knut

Youtube playlist

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

Publishing support is Edison , which has developed hundreds of site parsers and a service for sending push notifications to the bank .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/313226/

All Articles