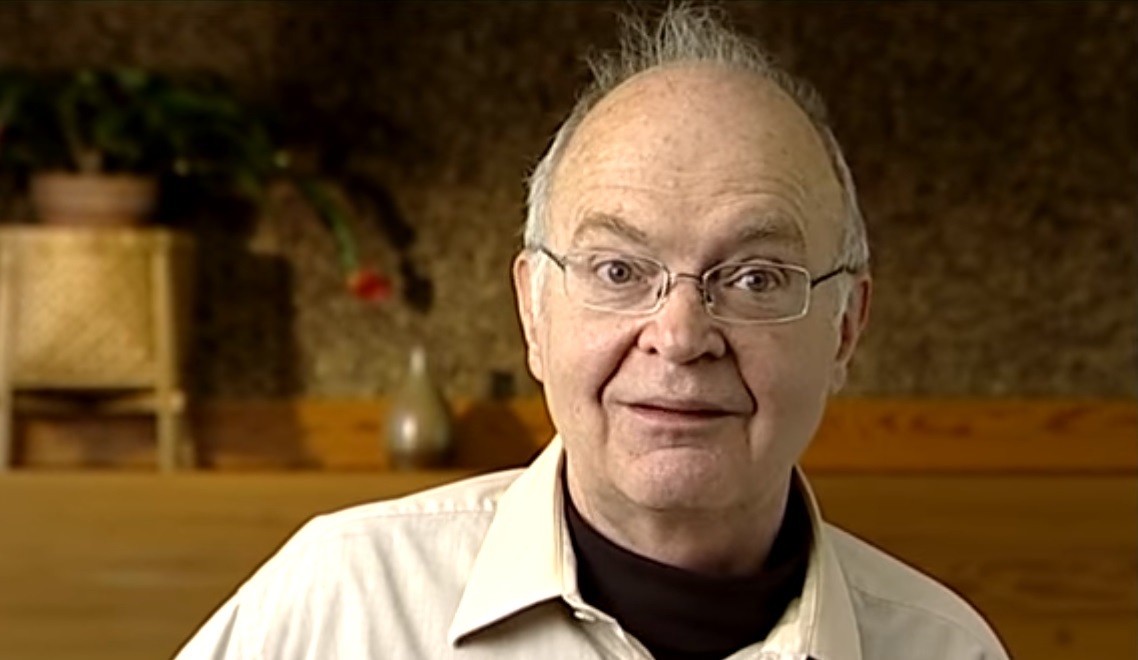

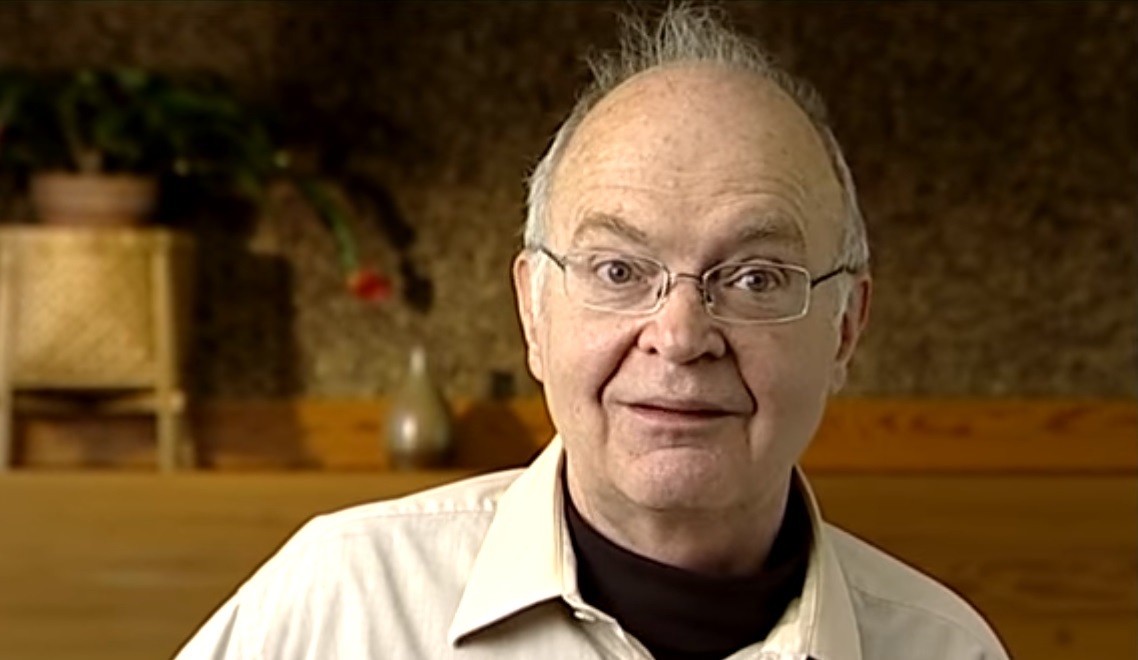

Donald Knut: How the “Art of Programming” was created (33,38,39 / 97)

“I had to finish the book before my son was born. Now he is 40 years old, and I still have not finished it. ”

In the third year of my stay at the university, I was asked to spend a couple of classes on computers. A handful of people said that Caltech (Caltech) was not learning anything related to computers. At that time, I was consulting Burroughs. “So why don't you spend a couple of classes at the university?” They asked me. So I held a lesson only once, and before graduating from university, they decided to hire me as an assistant professor immediately after graduation.

')

Usually the university does not hire its own graduates, with the exception of MIT. But as you know, it is considered bad to do inbreeding (incest), because the department can get bogged down in one philosophy, and they want "fresh blood." But Caltech found me quite strange and alien by blood, and this was a good reason to hire me.

(1:04) In the meantime, in January 1962, was my second year at the university and the first year of marriage with my wife. We were married in the summer of 1961. Jill and I lived in bliss for 6 months. We spent the honeymoon and then we had a little more time to be together until I plunged into writing a book on computer science.

In January 1962, an editor from Addison-Wesley invited me to dinner, and said: "We would like to suggest you write a book about compilers." (Compilers are what I did for Burroughs all of the previous year.)

Addison-Wesley is an American computer publishing company that has also previously published natural science literature. Belongs to the Pearson media concern.

“You were recommended to us as someone who can write compilers, and are you thinking about writing a book?” I used to work on all sorts of newspapers and magazines, I wrote several articles. I always liked to write. And the publisher of my favorite textbooks, Addison-Wesley, asks me to write a book.

(3:00) I immediately went home and wrote down the title of the 12 chapters and thought that it would be nice if the book were like that. I thought I could finish the book pretty quickly. I have a letter that I wrote in 1964 in response to an invitation to one university: “I unfortunately cannot visit Stanford University this year, because I have to finish the book before my son is born.

Now he is 40 years old, and I still have not finished the book ... I would like to finish it quickly, but I had no idea how and how much time I would need. I was asked to write a book about compilers, but I said: “Just a minute, there are a lot of things that happen in computer programming that you should also know about.” And they said they did not mind if other topics related to programming were covered in the book.

We decided to call the book “The Art of Computer Programming”. Publishers liked the title.

I decided to write “The Art of Programming” not because I like to write, but because I felt an acute need for such a book. Nothing like this at that time existed. Although I wrote several compilers, and knew a lot about them, I did not come up with any original idea in this area. I just applied ideas that I learned from other people. And I began to wonder who could write a book about compilers, but found all candidates biased and focused only on their approach.

I found only one candidate worthy for such a job, which he wrote was not biased - himself.

Draft contents contained 12 chapters. From the first day I began to fill out chapter by chapter and write more material, and in the meantime computer science was developing rapidly. It turned out that I greatly underestimated how long the work could last. At the end of the writing, I looked at my notes, they were all written by hand, and it seemed to me that my notes are much more than the book itself. In fact, I ... I came to the end of Chapter 12, I had 3000 pages. And I just planned 64-65 chapters ...

I have accumulated 3000 handwritten pages. I wrote to Addison-Wesley and asked if they would mind if I supplemented the book with the materials I dug up. To which I replied: "Come on."

(1:36) 3,000 pages. I took a typewriter and started typing. In the first chapter there were 400 pages of machine text and this is in two intervals. By the way, I typed on IBM Selectric. At the time, it was one of the best typewriters. As I was told later, I was the first private, and not the corporate buyer of such a machine. The beauty is that it has implemented a "buffer". That is, you could enter a new letter before the previous ones were printed. I first saw such a machine at the exhibition and tried to print a couple of sentences. I was delighted. And so I bought myself Selectric and used it for my dissertation at Caltech. It was as if I was a keyboard man: I played the piano, the saxophone, so it was just another machine with keys.

(3:50) I started typing, typed in the first chapter of twelve, and sent it to Addison-Wesley, saying, "This is the first chapter of my book." Then I received a letter from a person who actually was the first editor who spoke to me in 1962. But it was 1966, I think by that time I already had 3000 pages plus a recruited chapter. And now I heard the same guy again, but he was raised three steps in the company during that time, so now he was on his way up. And, you know, he said: “What is happening? Your book, Don, do you understand that your book will take more than 2000 pages? ”

What? I thought I had six or seven hundred pages in a book. I said, you know, I thought: “I have been reading books for years. How can you tell me that this book will be so long? ”So I went back to“ Thomas's Calculus ”(matan textbook), the original book, which I adored in my first year at college, and published.

I felt that the five pages I was typing would turn into one page in the book, but they said, "No, no, one and a half to one." I could not believe it. So I took “Thomas's Calculus” and typed 2 pages from there on my typewriter. Similarly, the three pages of typewritten text turned into two.

I had a book three times larger than I expected. No wonder it took me so much time to finish this thing. But then they said: "No one can master this book." You know, all publishers have horror stories about professors who send them manuscripts in 10 volumes about the history of eggs or something like that, and they just lie. And how are they going to get around this problem?

I flew to Massachusetts to discuss our future plans. The guys from the publisher said: "Well, we will think of something," although they have already managed to show this chapter to a few people who really liked it, and did not particularly doubt it. However, during lunch, I noticed at my then-editor, Norma Staaton, in my personal notes, “a strict budget constraint” or something like that. Apparently, he wanted to gently take me to this news, and suggested ... That is, they suggested not to bother with writing answers to the exercises, but instead of professional illustrations, insert the ones that I myself drew in the manuscript. The guys said that they are “enchanted” by them. I then, honestly, thought that they were drunk or stoned. “No,” I said, “know why I like Addison-Wesley?” Because the quality of their books is exactly what it should be - great, and the illustrations in them are up to standard. And that's why I signed a contract with you guys! ”After this conversation, my editor approached me and said:

“You were fearless and persevering, standing in front of the campaign director, well done, boy!”

And stuff like that. Then they decided to print this book in three volumes, but then their opinion changed, and they decided to release it already in seven volumes ... In general, the plan for publishing the book “The Art of Programming” in seven volumes was approved. And we still officially adhere to this plan, but over the past 30 years only 3 volumes have been released. Now I'm working on the fourth.

Computer science is a very vast area, and the 3,000 pages I wrote previously described its condition only for 1965. But a lot of time has passed since then, I studied some of its other aspects, which were also worth including in the book. Thus, several more stages passed. The guys also asked me not to include in the book the answers to the exercises; it was thought that they would be published separately, in paperback, and printed on a typewriter. However, the editors, nevertheless, decided to print the answers along with the rest of the text. And finally, in 1968, the first volume was released. And he was evaluated, to put it mildly, expensive - as much as $ 32! When the rest of the computer science books cost about $ 10. And what is amazing, in the very first year the book gained great success, 50 universities approved it as a textbook. And although it was not easy to read it, it proved that in this area there had not been enough books of this type for a long time.

This is how the history of the Art of Programming began. In 1968 I first received copies of the first volume. Since then, another 400,000 copies have been sold in English and much more in other languages. I could not believe that this book would become so popular. But if in 1962 I knew that at 68 I would still continue to work on it, I would definitely abandon this undertaking. To be honest, I thought I would finish in 1965, right before the birth of my son.

To be continued ...

Translation: Alena Karnaukhova, Katya Shershneva and Nikita Gladyshev

Publication support is the Edison company, which develops a web interface for controlling a radio relay station , as well as designs and develops software for recording and analyzing heart rate variability .

In the third year of my stay at the university, I was asked to spend a couple of classes on computers. A handful of people said that Caltech (Caltech) was not learning anything related to computers. At that time, I was consulting Burroughs. “So why don't you spend a couple of classes at the university?” They asked me. So I held a lesson only once, and before graduating from university, they decided to hire me as an assistant professor immediately after graduation.

')

Usually the university does not hire its own graduates, with the exception of MIT. But as you know, it is considered bad to do inbreeding (incest), because the department can get bogged down in one philosophy, and they want "fresh blood." But Caltech found me quite strange and alien by blood, and this was a good reason to hire me.

How the book idea was born

(1:04) In the meantime, in January 1962, was my second year at the university and the first year of marriage with my wife. We were married in the summer of 1961. Jill and I lived in bliss for 6 months. We spent the honeymoon and then we had a little more time to be together until I plunged into writing a book on computer science.

In January 1962, an editor from Addison-Wesley invited me to dinner, and said: "We would like to suggest you write a book about compilers." (Compilers are what I did for Burroughs all of the previous year.)

Addison-Wesley is an American computer publishing company that has also previously published natural science literature. Belongs to the Pearson media concern.

“You were recommended to us as someone who can write compilers, and are you thinking about writing a book?” I used to work on all sorts of newspapers and magazines, I wrote several articles. I always liked to write. And the publisher of my favorite textbooks, Addison-Wesley, asks me to write a book.

(3:00) I immediately went home and wrote down the title of the 12 chapters and thought that it would be nice if the book were like that. I thought I could finish the book pretty quickly. I have a letter that I wrote in 1964 in response to an invitation to one university: “I unfortunately cannot visit Stanford University this year, because I have to finish the book before my son is born.

Now he is 40 years old, and I still have not finished the book ... I would like to finish it quickly, but I had no idea how and how much time I would need. I was asked to write a book about compilers, but I said: “Just a minute, there are a lot of things that happen in computer programming that you should also know about.” And they said they did not mind if other topics related to programming were covered in the book.

We decided to call the book “The Art of Computer Programming”. Publishers liked the title.

I decided to write “The Art of Programming” not because I like to write, but because I felt an acute need for such a book. Nothing like this at that time existed. Although I wrote several compilers, and knew a lot about them, I did not come up with any original idea in this area. I just applied ideas that I learned from other people. And I began to wonder who could write a book about compilers, but found all candidates biased and focused only on their approach.

I found only one candidate worthy for such a job, which he wrote was not biased - himself.

Underestimation of book size

Draft contents contained 12 chapters. From the first day I began to fill out chapter by chapter and write more material, and in the meantime computer science was developing rapidly. It turned out that I greatly underestimated how long the work could last. At the end of the writing, I looked at my notes, they were all written by hand, and it seemed to me that my notes are much more than the book itself. In fact, I ... I came to the end of Chapter 12, I had 3000 pages. And I just planned 64-65 chapters ...

I have accumulated 3000 handwritten pages. I wrote to Addison-Wesley and asked if they would mind if I supplemented the book with the materials I dug up. To which I replied: "Come on."

(1:36) 3,000 pages. I took a typewriter and started typing. In the first chapter there were 400 pages of machine text and this is in two intervals. By the way, I typed on IBM Selectric. At the time, it was one of the best typewriters. As I was told later, I was the first private, and not the corporate buyer of such a machine. The beauty is that it has implemented a "buffer". That is, you could enter a new letter before the previous ones were printed. I first saw such a machine at the exhibition and tried to print a couple of sentences. I was delighted. And so I bought myself Selectric and used it for my dissertation at Caltech. It was as if I was a keyboard man: I played the piano, the saxophone, so it was just another machine with keys.

(3:50) I started typing, typed in the first chapter of twelve, and sent it to Addison-Wesley, saying, "This is the first chapter of my book." Then I received a letter from a person who actually was the first editor who spoke to me in 1962. But it was 1966, I think by that time I already had 3000 pages plus a recruited chapter. And now I heard the same guy again, but he was raised three steps in the company during that time, so now he was on his way up. And, you know, he said: “What is happening? Your book, Don, do you understand that your book will take more than 2000 pages? ”

What? I thought I had six or seven hundred pages in a book. I said, you know, I thought: “I have been reading books for years. How can you tell me that this book will be so long? ”So I went back to“ Thomas's Calculus ”(matan textbook), the original book, which I adored in my first year at college, and published.

I felt that the five pages I was typing would turn into one page in the book, but they said, "No, no, one and a half to one." I could not believe it. So I took “Thomas's Calculus” and typed 2 pages from there on my typewriter. Similarly, the three pages of typewritten text turned into two.

I had a book three times larger than I expected. No wonder it took me so much time to finish this thing. But then they said: "No one can master this book." You know, all publishers have horror stories about professors who send them manuscripts in 10 volumes about the history of eggs or something like that, and they just lie. And how are they going to get around this problem?

Release of the first edition

I flew to Massachusetts to discuss our future plans. The guys from the publisher said: "Well, we will think of something," although they have already managed to show this chapter to a few people who really liked it, and did not particularly doubt it. However, during lunch, I noticed at my then-editor, Norma Staaton, in my personal notes, “a strict budget constraint” or something like that. Apparently, he wanted to gently take me to this news, and suggested ... That is, they suggested not to bother with writing answers to the exercises, but instead of professional illustrations, insert the ones that I myself drew in the manuscript. The guys said that they are “enchanted” by them. I then, honestly, thought that they were drunk or stoned. “No,” I said, “know why I like Addison-Wesley?” Because the quality of their books is exactly what it should be - great, and the illustrations in them are up to standard. And that's why I signed a contract with you guys! ”After this conversation, my editor approached me and said:

“You were fearless and persevering, standing in front of the campaign director, well done, boy!”

And stuff like that. Then they decided to print this book in three volumes, but then their opinion changed, and they decided to release it already in seven volumes ... In general, the plan for publishing the book “The Art of Programming” in seven volumes was approved. And we still officially adhere to this plan, but over the past 30 years only 3 volumes have been released. Now I'm working on the fourth.

Computer science is a very vast area, and the 3,000 pages I wrote previously described its condition only for 1965. But a lot of time has passed since then, I studied some of its other aspects, which were also worth including in the book. Thus, several more stages passed. The guys also asked me not to include in the book the answers to the exercises; it was thought that they would be published separately, in paperback, and printed on a typewriter. However, the editors, nevertheless, decided to print the answers along with the rest of the text. And finally, in 1968, the first volume was released. And he was evaluated, to put it mildly, expensive - as much as $ 32! When the rest of the computer science books cost about $ 10. And what is amazing, in the very first year the book gained great success, 50 universities approved it as a textbook. And although it was not easy to read it, it proved that in this area there had not been enough books of this type for a long time.

This is how the history of the Art of Programming began. In 1968 I first received copies of the first volume. Since then, another 400,000 copies have been sold in English and much more in other languages. I could not believe that this book would become so popular. But if in 1962 I knew that at 68 I would still continue to work on it, I would definitely abandon this undertaking. To be honest, I thought I would finish in 1965, right before the birth of my son.

To be continued ...

Translation: Alena Karnaukhova, Katya Shershneva and Nikita Gladyshev

Read more

- Donald Knut: I sat in the back row and hunted jokes, and the teachers resigned and didn't often beat on the ass (1,2,3,7 / 97)

- Donald Knut: “My advice to the young” (93/97) and “Feeling the need to assert oneself” (9/97)

- Surreal Numbers: I worked for six days, and rested on the seventh (40,41,42 / 97)

List of 97 videos with stories of Donald Knut

Youtube playlist

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

1. Family history

2. Learning to read and school

3. My mother

4. My parents' finances

5. Interests in high school

6. Being a nerd of nerds at high school

7. My sense of humor

8. The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures

9. Feeling the need to prove myself

11. University life: my basketball management system

12. University life: the fraternity system

13. Meeting my wife Jill

14. Bible study

15. Extra-curricular activities at Case

16. Taking graduate classes at Case

17. Physics, welding, astronomy and mathematics

18. My maths teacher at Case and a difficult problem

19. My computer experience

20. How I got interested in programming

21. Learning how to program on the IBM 650

22. Writing a tic-tac-toe program

23. Learning about Symbolic Optimum Assembly programs

24. The Internal Translator

25. Adding more features to RUNCIBLE

26. Want to go to Caltech

27. Writing a compiler for the Burroughs Corporation

28. Working for the Burroughs Corporation

29. Burroughs Corporation

30. My interest in context-free languages

31. Getting my PhD and the problem of symmetric block designs with ...

32. Finding a solution to the problem of projective planes

33. Inception of The Art of Computer Programming

34. 1967: a turbulent year

35. Work on attribute grammars and the Knuth-Bendix Algorithm

36. Being creative in the forest

37. A new field: analysis of algorithms

38. The Art of Computer Programming: underestimating the size of the ...

39. The Art of Computer Programming

40. Inspiration to write Surreal Numbers

41. Writing Surreal Numbers in a hotel room in Oslo

42. Finishing the Surreal Numbers

43. The emergence of computer science

44. I want to do computer science instead of arguing for it

45. A year doing National Service in Princeton

46. Moving to Stanford and wondering whether to make the right choice

47. Designing the house in Stanford

48. Volume Three Of The Art Of Computer Programming

49. Working on the Volume.

50. Poor quality typesetting on the second edition of my book

51. Deciding to make my own typesetting program

52. Working on my typesetting program

53. Mathematical formula for letter shapes

54. Research into the history of typography

55. Working on my letters and problems with the S

56. Figuring out how to typesetting

57. Working on TeX

58. Why should the designer

59. Converting Volume Two to TeX

60. Writing a users manual for TeX

61. Giving the Gibbs lecture on my typography work

62. Developing Metafont and TeX

63. Why I chose and transcribed it to ...

64. Tuning up my fonts and getting funding for TeX

65. Problems with Volume Two

66. Literate programming

67. Re-writing TeX using the feedback I received

68. The importance of stability for TeX.

69. LaTeX and ConTeXt

70. A summary of the TeX project

71. A year in Boston

72. Writing a book about the Bible

73. The most beautiful 3:16 in the world

74. Chess master playing at Adobe Systems

75. At MIT

76. Back to work at Stanford

77. Taking up swimming help to help me cope with stress

78. My graduate students and my 64th birthday

79. My class on Concrete Mathematics

80. Writing a book on my Concrete Mathematics class

81. Updating Volumes of Computer Programming

82. Getting Started on The Fourth of The Art of Computer ...

83. Two final major research projects

84. lucky life

85. Coping with cancer

86. Honorary doctorates

87. The Importance of the Kyoto Prize

88. Pipe organisms of life

89. The pipe organ in my living room

90. Playing the organs

91. An international symposium on the Soviet Union

92. The Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

93. My advice to young people

94. My children: John

95. My children: Jenny

96. Working on a series of books

97. Why I chose analysis

Publication support is the Edison company, which develops a web interface for controlling a radio relay station , as well as designs and develops software for recording and analyzing heart rate variability .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/312796/

All Articles