Countdown: a book about Stuxnet, malware researchers and vulnerable critical infrastructure

Well, it's time to try yourself in the genre of the book review. The book Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the Launch of Worlds First Digital Weapon journalist Kim Zetter, best known for her articles in Wired magazine , was published quite a long time ago, in November 2014, but has not been translated into Russian since. (available in English, for example, in Amazon in electronic form ). However, the matter is not in translation: the Stuxnet history can also be studied from open publications and research by security experts, but in this case you will receive a range of technical facts about malicious code, from which it is not so easy to put together the puzzle of the whole story.

Well, it's time to try yourself in the genre of the book review. The book Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the Launch of Worlds First Digital Weapon journalist Kim Zetter, best known for her articles in Wired magazine , was published quite a long time ago, in November 2014, but has not been translated into Russian since. (available in English, for example, in Amazon in electronic form ). However, the matter is not in translation: the Stuxnet history can also be studied from open publications and research by security experts, but in this case you will receive a range of technical facts about malicious code, from which it is not so easy to put together the puzzle of the whole story.“Countdown” is a successful attempt to rise above the lines of code, to bring together everything that is known about the first and to this day the most large-scale specialized attack on industrial systems. At the same time, the book does not replace facts with a drama and is as far as possible from fiction. Its value is also in the fact that it shows the process of researching malicious code in a little more detail than usual: about half of the text is dedicated to this: from detecting code and identifying an attack, to analyzing zero-day vulnerabilities and, finally, analyzing modules that modify industrial controllers.

Six years have passed since the discovery of Stuxnet, seven years since the beginning of the attack, more than ten, presumably from the beginning of development. This is not the only cyber attack aimed at sabotage in industrial systems, but it still has no equal in complexity. This is partly good news, but the reason is not the increased security of industrial systems, but rather the change of reference points from customers. “Countdown” is a book about an attack, which was once called a “blockbuster” of information security, but it is also a book about the work of researchers - those who analyze malicious code and design protection against it, regardless of the source of the attack and intentions.

Format

Kim Zetter almost immediately goes from describing events at the Iranian uranium enrichment factory, based on data from the international organization IAEA , to the detection of a malicious program by experts from the Belarusian company VirusBlokAda, and here Kim Zetter had to decide on the narrative format. It is impossible to tell the story of Stuxnet without resorting to technical terms, but if you go deep into technology, there is a chance to lose a reader who is not related to the information security industry (that is, almost all readers). At least at the beginning of the book, a sacrifice to an imaginary cyberpunk deity still has to be brought, and it looks like this:

')

Stuxnet used a zero-day vulnerability in Microsoft Windows, so it could be distributed on USB-drives. And zero-day vulnerability is ...

To hide infected files on a flash drive, a rootkit was installed on the system, and the rootkit is ...

The malicious code was signed by digital certificates that were legitimate at that time, so that the installation was as transparent as possible to the user. And digital certificates are ...

And so on. Since the book is based on numerous interviews with researchers, Kim Zetter eventually brings a significant part of the facts in the footnotes, they sometimes take up no less space than the chapter relating to them. In the future, in the book, virtually all of the furious factology is there: you are given the choice to read the whole or skip the clarifications. In the latter case, the perception of the plot does not suffer, and thanks to the footnotes with a huge number of references to sources, the book turns out to be equally attractive for techies and for humanities scholars.

Ziro day

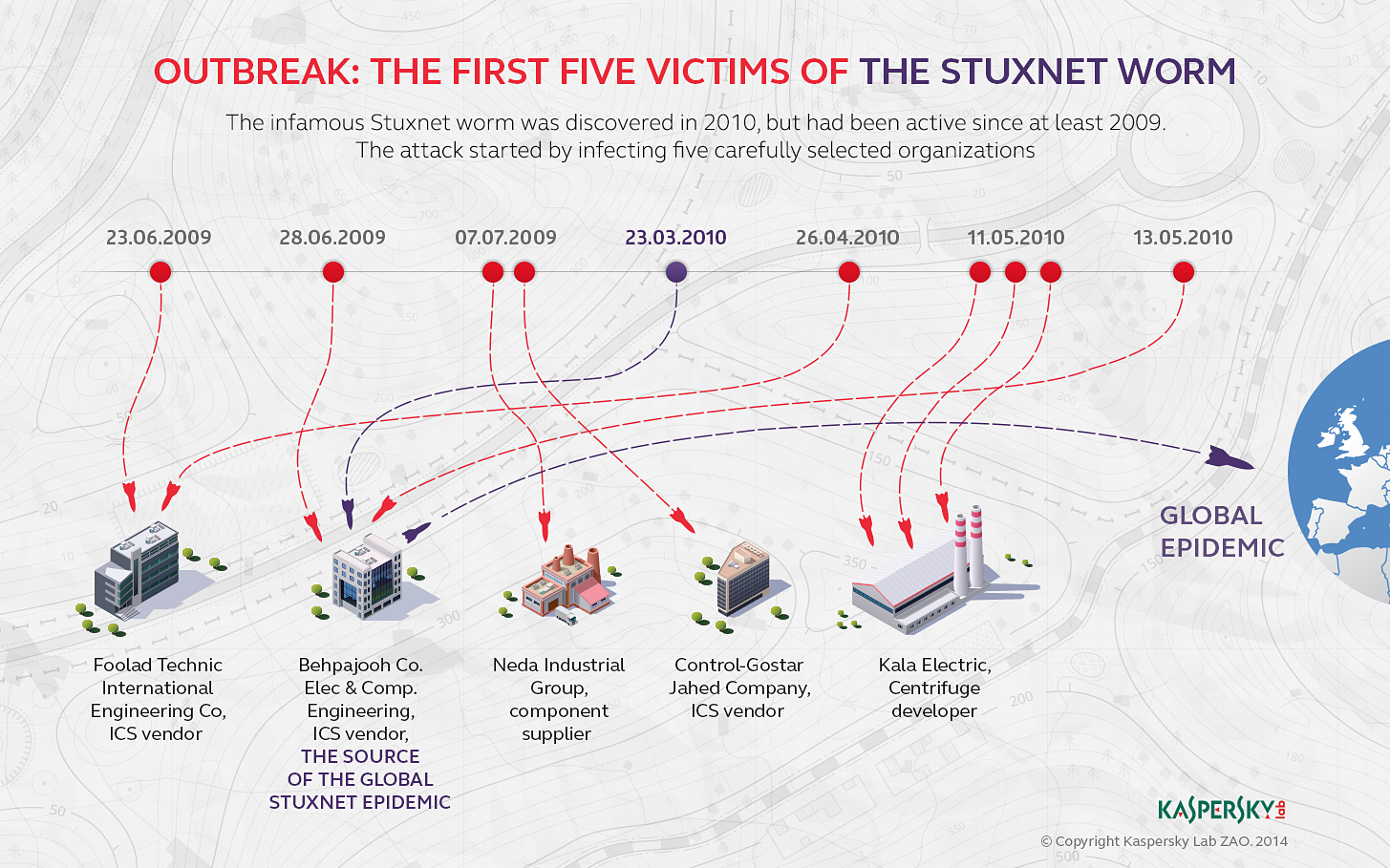

To infect, Stuxnet used the zero-day vulnerability in Windows operating systems - at the time of detection (July 2010, a bulletin on Technet) all current versions from XP to 7, 32 and 64-bit were exposed to it (Stuxnet attacked only 32-bit OS ). The vulnerability allowed launching malicious code using a prepared .LNK file or .PIF file. If it was placed on a USB flash drive, the vulnerability was automatically activated. It is this type of vulnerability allowed to attack the industrial system of critical importance, which is usually (but not necessarily) isolated from the network. Subsequently, our experts published an analysis of the first victims of Stuxnet, through which successful attempts to reach the main goal were likely made. The analysis became possible due to the preservation inside the malicious code of information about previously attacked systems.

Vulnerability was discovered only through the detection and investigation of Stuxnet. The use of zero-day vulnerabilities has become a feature of complex attacks. But over the past time, the situation has changed - not every successful targeted attack uses zero-days. Effective exploration and exploration of potential victims makes the use of similar, very expensive and quickly disclosed tools optional. Actually, in the Stuxnet investigation, the fact of using the zero-day vulnerability was established first of all, much more time and effort was needed for the analysis of the "payload".

In addition to the LNK vulnerability, Stuxnet used the MS08-067 vulnerability and another zyrodey, a hole in the Print Spool Service system ( MS10-061 ). Notably, the first vulnerability was also used by the Conficker worm, which caused a serious epidemic in 2008. The strange purpose of this malware in the light of Stuxnet even led to speculations that it was some kind of test-drive technology in the real world, but in fact the connection between these two attacks looks dubious.

Attribution

Who stood on the attack of Stuxnet is not known for certain. A significant part of Kim Zetter's book is devoted to attribution in its two senses: when the connection with some people, events or other attacks is derived from the malicious code, and when the “authors of the event” confirm the authorship of the attack. With the second, in fact, everything is not very good: despite the mass of statements and arguments from various parties, it is impossible to reliably prove involvement in the development of Stuxnet of any country, and, most likely, the situation will not change for many years. Here, the “Countdown” narrative loses a bit of rhythm, despite the equally painstaking work done by the author to collect data from various sources.

But the attribution in the code analysis process is an interesting thing. As one of the first examples, there is a line from the Stuxnet code:

b:\myrtus\src\objfre_w2k_x86\i386\guava.pdb If you temporarily distract from reverse engineering and study (for a change) the Old Testament, you can see in this line a reference to the Jewish holiday of Purim, which means it may be some kind of transparent hint at the authorship of the code. What just do not have to do the researchers. In fact, the presence in the code of the line with the original path to one of the files on the developer’s machine could have been left intentionally to confuse the traces. Another version that “myrtus” is not at all “myrtle” and a hint, but just an abbreviation of “my remote terminal units”.

Followers

But evidence of a connection between Stuxnet and the later discovered attacks by Duqu and Flame was ample. In the case of Duqu , the same platform was clearly used as for Stuxnet. Flame is not related to the Stuxnet / Duqu codebase, but used the same vulnerabilities, including a hole in the Print Spool Service. Both attacks were analyzed in as much detail as possible by the specialists of the Laboratory, and the book in the respective chapters uses information from interviews with our experts. Curiously, Duqu and Flame had no destructive functions and were used primarily for cyber espionage. Given the focus of almost all complex attacks since the discovery of Stuxnet, information is valued above sabotage. This, however, does not mean that industrial facilities are now safe.

Imaginary complexity of critical infrastructure

Understanding exactly what Stuxnet's main goal was was not easy — the researchers simply had no experience with SCADA systems. The book describes in detail exactly how this part of the code was analyzed: Stuxnet, in the event of a system infection with a specific software, could control the controllers of a strictly specified model, and thus alter the rotation speed of the centrifuges (presumably) at the facility in Iran so that they would fail from excessive load. Details of the logic of Stuxnet work in this direction was investigated by Symantec specialists (report in PDF ). Interestingly, to detect attacks and protect computers even in the absence of (for several weeks) a patch for Microsoft's vulnerabilities, knowing what Stuxnet was doing was not necessary. Such information is important only in the context of preparation for repelling future attacks of this type.

Kim Zetter devotes a separate chapter to the safety of industrial IT systems in general. Examples are given, albeit incomparable in scale to Stuxnet, sabotaging similar objects with the help of malicious code or by intercepting control systems. The fact that the industrial infrastructure is already sufficiently computerized to be vulnerable, but still not sufficiently protected, has been known for a long time. Alas, it is impossible to say that Stuxnet radically and irrevocably changed the situation for the better: very often the operators of critical objects rely on the isolation of control systems, and on the complexity of proprietary protocols. There are also objective difficulties: a long cycle of equipment operation, specific requirements for hardware and software, the belonging of industrial IT systems and traditional computer infrastructure to different teams within one company, and inevitable problems at the interfaces. However, Stuxnet clearly attracted the attention of cybersecurity researchers to the problem: since 2012, according to our report , the number of detected and closed vulnerabilities in specialized software has increased significantly. On the other hand, the same report shows how the search through Shodan this year allows you to find more than 180,000 hosts with elements of SCADA-systems that are directly accessible through the network.

findings

In my opinion, the Stuxnet story, described in its most comprehensive manner in the book “Countdown to Zero Day”, allows us to draw several important conclusions that are relevant to attacks (and to protect against them) of today's day:

- The authors of even the most advanced cyber attacks make mistakes. Most likely, as a result of an erroneous action at a certain stage, there was a massive infection of thousands of systems in different countries, which made it possible to notice and analyze the malicious code (however, there is a version that this was done intentionally). Moreover, for the first time, the Stuxnet sample was discovered due to a complaint about a computer that was constantly rebooting - something went wrong during the infection process. Here lies the danger of developing dangerous cyber weapons: methods of attack sooner or later become widely known, and tools may fall into the wrong hands.

- You can not rely on the complexity of systems and protocols. The concept of security through obscurity was ultimately recognized as ineffective by Stuxnet. Yes, it took a lot of manpower and resources to develop this attack (according to some estimates, from 5 to 30 developers and at least 6 months of work), and yes, at first the researchers faced difficulties in analyzing specialized code for the process control system. The parallel experience of analyzing attacks on financial systems since last year shows that even the most complex systems can be hacked, and control over them can be used to cause damage.

- The information security industry effectively fights complex attacks only when working together. The study of Stuxnet, as well as Duqu and Flame, involved many vendors of security solutions and independent researchers. Analyzing someone else's code is difficult and time-consuming, even for highly skilled professionals. Stuxnet was one of the first examples when cooperation and public sharing of results allowed for faster research and development of protection. Fortunately, this is not the last example, but the interaction of the “security men of the whole world” still needs to be worked on.

- The history of complex and most destructive cyber attacks with the detection of Stuxnet has not ended, but has just begun. Our map of advanced attacks is a clear proof of this. Although the theft of information is the priority objective of the attackers, it is impossible to forget about the protection of industrial systems and critical infrastructure - if only because even single successful operations at such facilities can lead to enormous damage. Despite the complexity of industrial systems, resources are needed for their research from a security point of view and adequate protection methods.

- And finally, being a cyber threat researcher is cool. The book by Kim Zetter is a rare case when, in addition to the lines of code and conclusions, the work of security experts is shown in an accessible form by the example of a very real attack. Such activities are very difficult to describe popularly, but, given the number of threats and their complexity, the maximum penetration of digital systems into our everyday life, we need to do this more and more often.

Disclaimer: This column is based on real events, but still reflects only the personal opinion of its author. It may coincide with the position of Kaspersky Lab, or it may not coincide. Then how lucky.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/310398/

All Articles