In memory of Solomon Golomb (1932-2016): the author of the shift register with linear feedback of maximum length and polynomial

Translation of Stephen Wolfram's post " Solomon Golomb (1932–2016) ".

I express my deep gratitude to Polina Sologub for assistance in translating and preparing the publication.

Content

- The most commonly used mathematical algorithm in history

- How I met Saul Golomb

- The story of Solomon Golomb

- Shift registers

- Background to shift registers

- What are the sequences generated by shift registers?

- Well, where are these registers?

- Cellular automata and shift registers with non-linear feedback

- Poliomino

- The rest of the story

The most commonly used mathematical algorithm in history

Octillion . Billion billion billion. This is a very rough estimate of how many times a mobile phone or other device has generated a bit with a linear feedback shift register of maximum length . I think this is the most used mathematical algorithm in history. The author is Solomon Golomb , who died on May 1, with whom we have been acquainted for more than 35 years.

')

The basis of the book of Solomon Golomb "Register Shift Sequences" , published in 1967, were his works of the 1950s. And its content lives in each of the modern communication systems. Read the specifications for 3G , LTE , Wi-Fi , Bluetooth, or even GPS , and you'll find references to polynomials that define the sequences generated by the shift registers that these systems use to encode the data they send. Solomon Golomb - the man who created these polynomials.

In addition, he played an important role in calculating the distance to Venus using radar, as well as in the development of image coding for sending from Mars. He presented to the world what he called polynomino (which later inspired the creators of Tetris - "Tetromino tennis"). He created and solved countless math puzzles and puns. About 20 years ago I learned that he was very close to the discovery of my favorite rule 30 for cellular automata back in 1959, when I was just born.

How I met Saul Golomb

Almost all the scientists and mathematicians with whom I am familiar, I learned through my professional connections. But not Sol Golomb. It was 1981, and I, a 21-year-old physicist (who became little known in the media because he was the youngest recipient of the MacArthur Prize at the first awards ceremony) did research at Caltech . They knocked on the door of my office, and soon a young woman stepped over the threshold. This was already unusual, because in those times, where theoretical high-energy physics was involved, there were hopelessly few women. Although I lived in California for several years, I, nevertheless, did not leave the university, and therefore I was not well prepared for the surge in Southern Californian energy, which burst into my office. A woman introduced herself to Astrid and said she was visiting Oxford and knew someone I was in kindergarten with. She explained that she was instructed to collect information about interesting people in the Pasadena area. I think she considered me a difficult case, but, nevertheless, insisted on talking. And one day, when I tried to tell something about what I was doing, she said: " You have to meet my father. He is already an old man, but his mind is still sharp as a razor ." And so it happened that Astrid Golomb, the eldest daughter of Sol Golomb, introduced me to him.

The Golomb family lived in a house located in the mountains near Pasadena. They had two daughters: Astrid - a little older than me, an ambitious Hollywood girl, and Beatrice - about my age and scientific mentality. The Golomb sisters often held parties — usually at home. The themes were different: this is a garden party and a croquet with flamingos and hedgehogs ("the winner will be the one whose suit will most closely match the stated theme "), or the Stonehenge party with instructions written in runes. At these parties intersected young and not very people, including - various local luminaries. And on them, a little to the side, there was always a small man with a big beard, a bit like an elf and always wearing a dark coat - Solomon Golomb himself.

Gradually, I learned a little about him. That he was involved in " information theory ". That he worked at the University of Southern California . The fact that he had various uncertain, but, apparently, high-level government and other ties. I heard about shift registers, but knew almost nothing about them.

In the fall of 1982, I visited Bell Labs in New Jersey and made a presentation on my latest results in the field of cellular automata. One of the topics that I discussed was “additive” (or “linear”) cellular automata , as well as their behavior with a limited number of cells . Whenever a cellular automaton has a limited number of cells, its behavior will inevitably end up repeating itself ... However, as the size increases, the maximum repetition period, say, for rule 90 for an additive cellular automaton, seems to be jumping in a completely random fashion: 1 , 1, 3, 2, 7, 1, 7, 6, 31, 4, 63, ... However, a few days before the performance I noticed that these periods seem to follow a formula that depends on simple factors or the number of cells. But when I mentioned this, someone sitting far raised his hand and asked: “ Do you know if this works for n = 37? "In my experiments, I did not deal with this number, so I did not know. But why did someone ask me about it?

The one who asked me was called Andrew Odlyzhko - he was a theorist from Bell Labs. I asked him: " What makes you think that something special may be connected with n = 37 ? " “ Well, ” he said, “ I think what you are doing is related to the theory of linear feedback shift registers, ” and he suggested that I was watching the book by Sol Golomb. “ Oh, yes, ” I said, “ I know his daughters ... ” Andrew was right: there is a very elegant theory of polynomial additive cellular automata, similar to the Saul theory developed for linear feedback shift registers. Andrew and I have written a well-cited article about this now (this is the rare case when traditional mathematical methods allow us to describe the behavior of a cellular automaton). And for me, the side effect was that I learned something about what Solomon Golomb was doing (if you remember, it was all before the advent of the Internet).

The story of Solomon Golomb

Solomon Golomb was born in Baltimore, Maryland , in 1932. His family was from Lithuania . His grandfather was a rabbi, and his father, still very young, moved to the United States and received a master's degree in mathematics, after which he retired to medieval Jewish philosophy and also became a rabbi. Sol's mother came from a famous Russian family, who made boots for the tsarist army, and then led the bank. Saul succeeded in school, being the strongest in the debate. Inspired by his father, he was interested in mathematics and at the age of 17 published an article on prime numbers. After graduating from high school, he entered Johns Hopkins University to study mathematics, and almost got into the quota for Jewish students (so he had to promise that he would not go into medicine, and then Sol, having increased his load twice, graduated from university 1951 for half the usual period of study).

From there, he went to Harvard to graduate school in mathematics. However, before that, he worked in the summer at the Glenn L. Martin Company - an aerospace company founded in 1912, which in 1920s moved to Baltimore from Los Angeles and became a defense contractor, which ultimately resulted in Lockheed Martin . At Harvard, Sol specialized in number theory, and, in particular, on the characterization of sets of primes. But every summer he returned to the Martin Company. As he said later, at Harvard, "the question of whether any practical application had what it was taught and learned there could not even be spoken out loud, let alone discussed ." But in the Martin Company, he discovered that the pure mathematics he knew — even simple numbers — did have practical applications, including the shift register.

In the first summer of his work at the Martin Company, Sol was assigned to a management theory group. In the second summer, he was placed in a communication group. And in June 1954, it happened that his boss attended a conference where he heard about the strange behavior of a register shift with linear feedback, and he asked Saul if he could do this research. Soon, Sol realized that this topic could be explored using polynomials over finite fields. For the next year, he divided his time between graduate studies at Harvard and consulting for the Martin Company, and in June 1955 he wrote his final report, " Sequences with Random Properties, " which became fundamental to the theory of the shift register.

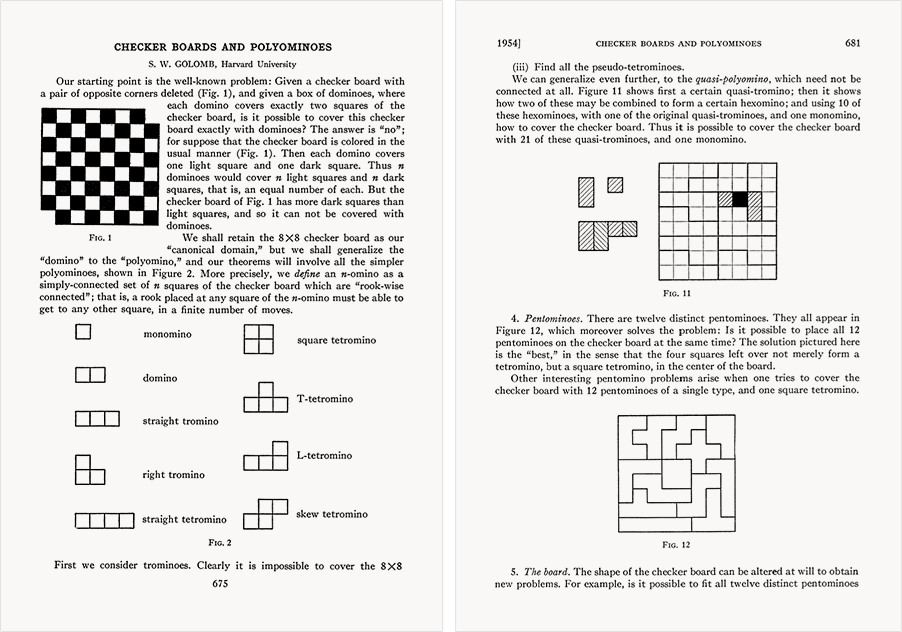

Saul loved mathematical puzzles, and in the process of thinking about puzzles with the organization of domino knuckles on a chessboard, he invented what he later called " poliomino ". He gave a report on them in November 1953 at the Harvard Mathematical Club, published an article about them (his first research paper) and won the Harvard Mathematical Award for working with them.

In June 1955, Saul left for a year at the University of Oslo for the Fulbright Fellowship program — partly to work with some outstanding theorists, partly to learn Norwegian, Swedish and Danish languages (and study some runic manuscripts) and replenish his collection language skills. During his stay in Oslo, he finished a long article on prime numbers and managed to travel around Scandinavia, and in Denmark he met a young woman named Bo (Bodil Rygaard) - she came from a large family and was born in a rural area known only for its peat moss, but managed to get to the university and studied philosophy. Sol and Bo, apparently, got along, and a few months later they got married.

When they returned to the USA in July 1956, Sol gave several interviews, and then went to work at JPL , a jet propulsion laboratory that separated from the California Institute of Technology and was involved in military development. Saul was included in the communications group as a senior research engineer. It was then when people from the laboratory were ready to launch a satellite. However, the government did not allow them, fearing that it would look like military action. That all changed in October 1957, when the Soviet Union launched its satellite, allegedly within the framework of the International Geophysical Year . Surprisingly, it took the US only 3 months to launch Explorer-1 . JPL did a lot to launch the satellite, and Sol’s group (where his technicians worked on implementing the register shift in electronic form) was thrown into creating radiation detectors; during this work, Sol was able to return briefly to Harvard to pass the final PhD exams.

It was a time of concentration of forces around JPL and the space program. In May 1958, a new information processing group was formed, led by Saul, and in the same month his first child, Astrid, was born. Saul continued his study of the sequences generated by shift registers with respect to jamming-resistant radio control. In May 1959, Sola’s second daughter appeared, who was named Beatrice (good sequence: A, B ...). In the fall of 1959, Saul took a sabbatical leave at MIT , where he met Claude Shannon and a number of other luminaries of MIT and worked on information theories and algebraic codes.

At that time, he had already done some work on coding theory in the field of biology. Although the digital nature of DNA was discovered by Jim Watson and Francis Crick as early as 1953, it was still not clear how exactly the sequences of four possible base pairs encode 20 amino acids. In 1956, Max Delbrück - a former adviser to Watson on a postdoc at California Tech - consulted on this issue with the staff of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Saul and two colleagues analyzed the idea of Francis Crick and came up with “comma-free codes” in which overlapping triples of base pairs can encode amino acids. Analysis has shown that exactly 20 amino acids can be encoded this way. This was one of the most amazing explanations; but, unfortunately, biology actually does not work that way (biology uses simpler coding, in which some of the 64 possible triples do not represent anything).

In addition to biology, Saul also studied physics. Its sequences generated by the shift registers came in handy for calculating range using radar (used in GPS); also Saul was put in charge of finding the distance to Venus. And it so happened that at the beginning of 1961, when the Sun, Venus and Earth lined up most successfully, Saul received a radar signal from Venus using the 85-foot Goldstone antenna located in the Mojave Desert , and clarified our data on Earth-Venus distances and the Earth-Sun.

Given Sola’s interest in languages, coding, and space, it is not surprising that he became interested in aliens. In 1961, he wrote an article for the Air Force called " A Short Guide to Extraterrestrial Linguistics ", and over the next several years wrote several articles on this topic for a wider audience. He said: “There are 2 main problems with regard to contact with aliens: one of them is the problem of finding a mutually acceptable channel. The other is a more philosophical problem (semantic, ethical and metaphysical), which consists in finding the proper subject for discussion. Simply put, we first need to find a common language, and then we have to think about what to say . ” Then he continued with his characteristic humor: “ Naturally, we should not tell them too much until we know if the intentions are noble enough of them. The government will undoubtedly create a Space Intelligence Directorate (KRU) to monitor extraterrestrial intelligence. Extreme measures will be taken . safety As once said HG Wells [or it was an episode of the Twilight zone ?] that, even if the aliens will tell us quite frankly that their only goal - "to serve humanity," we must find out, wish and they serve us in the baked or fried. "

During his work at JPL, Sol also taught at nearby universities: California Institute of Technology, the University of Southern California, and the University of Los Angeles . In the fall of 1962, after changing the situation in the laboratory (and, perhaps, because he wanted to spend more time with his young children), he decided to become a full-time professor. He received offers from all three universities. He wanted to go where he could work freely. He was told that at the California Institute of Technology " no one except the Nobel laureates has any influence, " and in Los Angeles " such a bureaucracy that no one can influence anything ." As a result, Saul chose the University of Southern California despite his low reputation. In the spring of 1963, he began to work as a professor of electrical engineering and eventually worked there for 53 years.

Shift registers

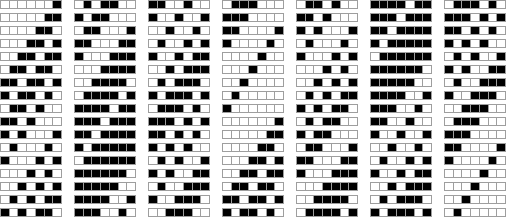

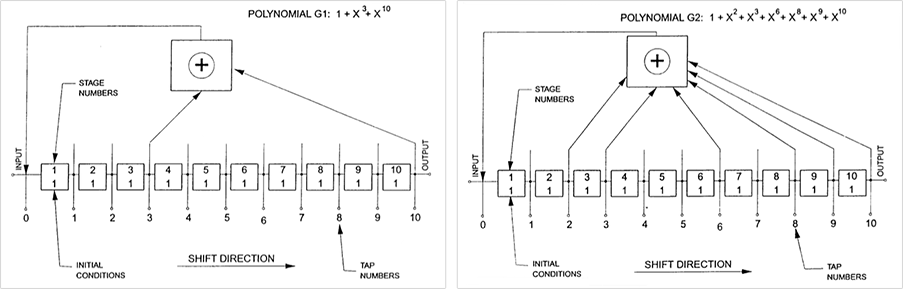

Before continuing with the story of Sol’s life, I must explain what a linear feedback shift register (LFSR) is. The basic idea is quite simple. Imagine a series of squares, each containing 1 or 0 (say, black or white). In a pure shift register, everything that happens is reduced to shifting all values one step to the left, while the leftmost value is lost, and the new value is taken from the right. The idea of a shift register with feedback is that the value that is shifted is determined (or “fed back”) depending on the values of the other positions in the shift register. In the linear shift register with feedback, the values from the “branches” in certain positions in the register are combined modulo 2 (so that 1⊕1 = 0 instead of 2), or XOR (" exclusive or ") is applied.

Here is what happens after a while:

As you can see, the shift register always shifts the bits to the left, and the other bits are added to the right according to a simple rule. The bit sequence seems random, although, as shown in the figure, it eventually repeats. Sol Golomb found an elegant mathematical way of analyzing such sequences and how they repeat.

If the shift register has size n, then it has 2 n possible states (corresponding to all possible sequences 0 and 1 for length n ). Since the rules for the shift register are deterministic, any given position must always come to another similar position. This means that the maximum possible number of steps that the shift register can pass before the steps start repeating is 2 n (actually 2 n - 1, since the position with all 0 cannot evolve into anything else).

In the example above, the shift register has a size of 7 and will repeat in exactly 2 7 - 1 = 127 steps. But which shift registers — with what branch locations — will produce maximum length sequences? This is the question Solomon Golomb began to explore in the summer of 1954. And his answer was simple and elegant.

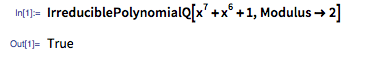

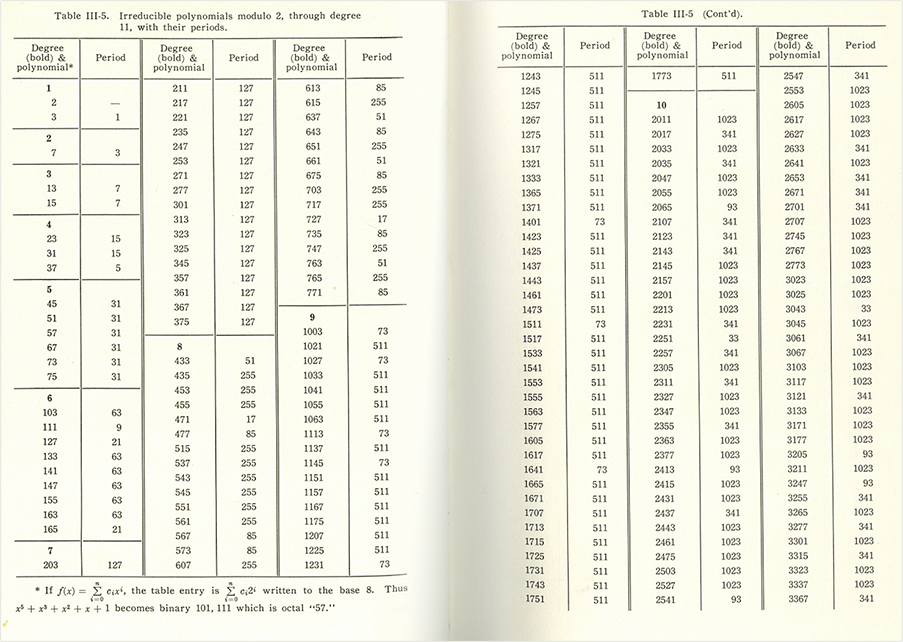

The shift register given above has branches in positions 7, 6 and 1. Sol introduced this algebraically, using a polynomial x 7 + x 6 + 1. He showed then that the generated sequence would be of maximum length if this polynomial is “ nonreducible modulo 2 ”; therefore, it cannot be factorized, which makes it an analogue of prime among polynomials; and the presence of some other properties makes it a " primitive polynomial ". Today it is easy to check with Mathematica and the Wolfram Language :

Then, in 1954, Sol had to do it all by hand; he compiled a rather long table of primitive polynomials corresponding to shift registers, which yielded sequences of maximum length:

History of shift registers

The idea of maintaining RAM by means of " delay lines ", which transmit digital pulses, goes back to the beginning of the computer era. By the end of the 1940s, such delay lines were applied in digital form using a series of vacuum tubes and were called “ shift registers ”. It is not clear yet when the first shift registers with feedback were created. Perhaps it was in the late 1940s. However, this event is still shrouded in mystery, because for the first time they were used in military cryptography.

The basic idea of cryptography is to change meaningful messages so that they cannot be recognized; however, if you know the key, you can recreate the encrypted message. The so-called stream ciphers work on the principle of creating long sequences of random elements, and are decoded using a receiver, which independently generates the same sequence of elements.

Linear feedback shift registers were valued in cryptography because of the long repetition periods. However, the mathematical analysis that Sol used to find these periods makes it clear that such shift registers are not suitable for secure cryptography. However, in the beginning they seemed to be quite good (especially in comparison with the successive positions of the rotor in Enigma ); there were persistent rumors that Soviet military cryptosystems were built on this basis.

Back in 2001, when I was working on historical notes for my book A New Kind of Science , Saul and I talked on the phone for a long time about register shifts. Sol told me that when he started, he knew nothing about cryptographic work on shift registers. He said that Bella Lab staff, Lincoln Laboratories and the Jet Propulsion Labs began working on shift registers around the same time as he; however, he was able to advance a little further, which he noted in his report of 1955.

Over the next years, Sol gradually learned about the various predecessors of his work from the literature on pure mathematics. Already in 1202, Fibonacci talked about what is now called Fibonacci numbers and which are generated by a recurrent relation (which can be considered as an analogue of a linear feedback shift register, working with arbitrary integers, and not with zeros and ones). There are also small works of the early 1900s with cycles of 0 and 1, however, the work of Oisten from the University of Oslo was the first large-scale study. Ore had a student named Marshall Hall who advised the predecessor of the National Security Agency in the late 1940s. - probably on the topic of shift registers. However, all that he did was classified, and therefore he agreed with Saul to publish the history of shift registers with linear feedback; Saul has dedicated his book to Marshall Hall.

What are the sequences generated by shift registers?

I have noticed many times that systems defined by simple rules end up with many variations of applications; shift registers also follow this pattern. Both modern equipment and software are crammed with shift registers: probably a dozen or two in a regular mobile phone, usually implemented at the hardware level, and sometimes in software (when I write here the shift register, I I mean the linear feedback shift register (LFSR).

In most cases, those shift registers are used that give sequences of maximum length (otherwise known as " M-sequences "). The reasons for which they are used, as a rule, are associated with some of their properties, which Sol discovered. They always contain the same number of 0 and 1 (although in fact there is always exactly one additional 1). Subsequently, Saul showed that they also have the same number of sequences 00, 01, 10, and 11 — and for large blocks, too. This property of " balance " is already very useful in itself, for example, if you test all possible combinations of bits as input data.

However, Sol discovered another, even more important property. Replace each 0 in the sequence with 1, then multiply each element in the shifted version of the sequence with the corresponding element of the original. Sol showed that when added, these elements will always be zero (except when there is no shift at all). That is, the sequence has no correlation with shifted versions of itself.

These properties will be true for any sufficiently long random sequence of 0 and 1. It is surprising that for sequences of maximum length these properties are always true. Sequences have some features of randomness, but in fact they are not at all chaotic: they have a well-defined, organized structure .

It is this structure inherent in linear feedback shift registers that makes them unsuitable for serious cryptography. But they are great for basic “permutation of elements” and cheap cryptography and are actively used for these purposes. Often the task is simply to “bleach” the signal (as in “white noise”). 0. , «» . , . Wi-Fi , Bluetooth , USB , TV , . .

— , ( DVD 16 24 ; GSM ).

GPS . GPS , , 10 . , . , , ( GPS, 1024 ).

- . , , . — " ", , 1 ( ) . CRC ( ), , . , , , , — , - , .

, , . , , — , ( «Enable Spread Spectrum» BIOS).

— CDMA ( ). , «», . «» ? «» . ( TDMA — ). CDMA .

, , , ( ) , . , , . 3G .

, . 1959 , . , . , 1968 Linkabit , ( ).

1985 Qualcomm . , 1990- , CDMA , .

?

, , , . . , , (PN, , M-, FSR, LFSR , MLS, SRS, PRBS, . .).

, , , , — , . 2G TDMA, , , CRC ( ) . 3G — CDMA, , , . 4G , , CRC : , , . 5G — , . , , «-», ; , .

, . , , , — , CRC ( ) , , , . ( PCIe , SATA . .): , , HDMI . CRC , , , .

, , . 10 , — , IoT (« ») . ( !) — 10 .

? , « », , ( CDMA) . , — .

10 , 1/10 ( 3- ), 1 , , .

? I think yes. , . , , . ? - .

« », , . (. " ( ) "), ( , , - , ). « », . ( " ", " " . .), , «» . , , , , ; , , , - .

Although at first glance this does not seem obvious, it turns out that there is a close relationship between shift registers with feedback and cellular automata, which I have studied for many years. The basic organization for a shift register with feedback involves calculating one bit at a time. In a cellular automaton, there is one cell line, and at each step all cells are updated in parallel, based on a rule that depends, for example, on the values of their nearest neighbors.

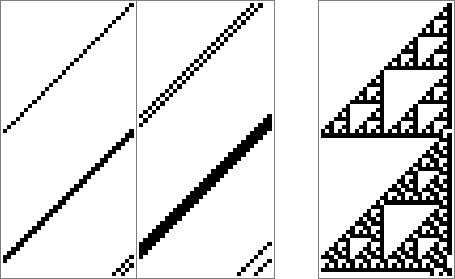

To see how they are related to each other, you need to run a shift register with feedback of size n , and at the same time display its state only every n steps; in other words, let all bits be overwritten before they reappear. If each step of the shift register with linear feedback (here - with two branches) is displayed, then at each step everything will shift to the left - that's all. But if you make a compressed picture, showing only every n steps, you will see a pattern.

This is an nested pattern; and this picture is very similar to the one that can be obtained if the cellular automaton takes the cell and its neighboring cell and adds them modulo 2 (XOR). This is what happens with the cellular automaton if it positions its cells so that they are in a circle of the same size as the shift register above:

Initially, cellular automata and shift register patterns are exactly the same. If you look at these pictures, it becomes less surprising that the math of shift registers should be related to cellular automata. And, given the recurrence of nested patterns, it becomes clear why there should be an elegant mathematical theory of shift registers.

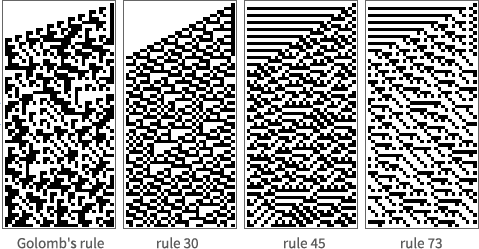

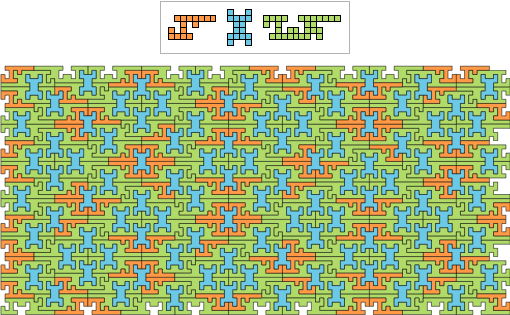

For typical shift registers used in practice, such clearly repeating patterns are not characteristic. Here are some examples of shift registers that generate maximum length sequences. The fact is that the branches are far from each other, which makes it difficult to find visual traces of nesting.

How wide is the correspondence between shift registers and cellular automata? For cellular automata, the rules for generating new cell values can be anything. In linear feedback shift registers, they must always be based on modulo 2 addition (or XOR). This is what the “linear” part of the “linear feedback shift register” means. It is also possible to use any rule to combine values for shift registers with non-linear feedback (NFSR).

Indeed, when Sol developed his theory for linear feedback shift registers, he began with a non-linear case. When he arrived at JPL in 1956, he received a laboratory complete with racks for small electronic modules. Sol said that the modules (each of them were the size of a cigarette pack) were built for the Bell Labs project to perform a certain logical operation (AND, OR, NOT, ...). The modules can be used together to implement any desired shift registers with non-linear feedback, providing about a million bits per second (Sol told me that someone tried to do the same using a universal computer and that took 1 second when using hardware modules, required 6 weeks of work on a universal computer).

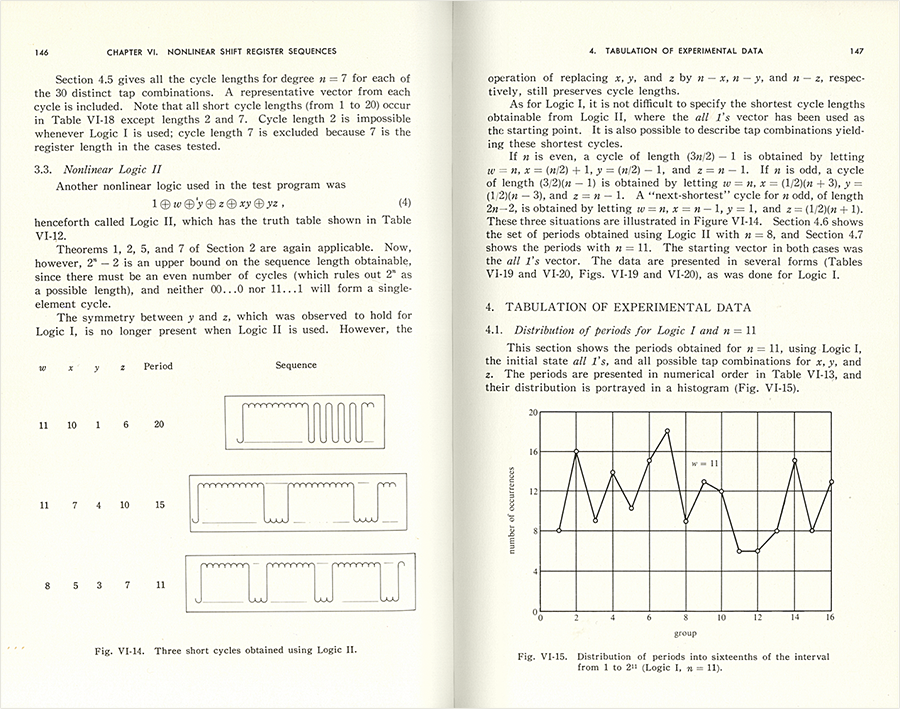

When Saul began to study the linear feedback shift registers, his first serious discovery was the periods of their repetition. And in the case of non-linear, he directed most of his efforts to trying to understand the same thing. He collected all kinds of experimental data. He told me that he even checked sequences of length 2 45 , which took a year. He made a summary, as in the image below (note the visualization of the sequences shown on the waveform line). But he did not manage to come up with some general theory, which he had for the shift registers with linear feedback.

It is not surprising that he could not do this. Already in the 1950s, theoretical results appeared (in most cases based on the ideas of Turing's universal calculations), which programs could in principle do this. I do not think that Sol or anyone else ever thought that very simple (non-linear) functions would be used in non-linear feedback shift registers.

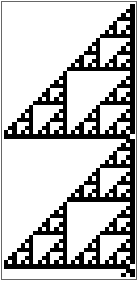

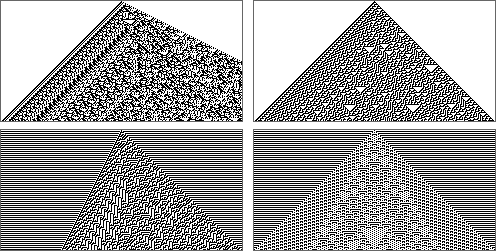

And only later it became clear how complicated the behavior of even very simple programs can be. My favorite example is rule 30 for a cellular automaton in which the values of neighboring cells are combined using a function that can be represented as p + q + r + q * r mod 2 (or p XOR ( q OR r ) ). Incredibly, Sol considered non-linear feedback shift registers based on similar functions: p + g + s + q * r + q * s + r * s mod 2 . Here, below, are illustrations of how the Saul function (which can be viewed as " rule 29070 "), rule 30, and a few other similar rules look in the shift register:

And here they are, not limited to a fixed-size register, similar to cellular automata:

Of course, Saul never made pictures like this (and even that was almost impossible to do in the 1950s). Instead, he focused on the repetition period as a kind of aggregate characteristic.

Saul wondered whether shift registers with non-linear feedback could be sources of randomness. From what is known today about cellular automata, it is clear that they can. For example, to create randomness for the Mathematica system, we used the rule of 30 cellular automata for 25 years (although we recently abandoned it in favor of a more efficient rule, which we found after examining trillions of possibilities).

Saul talked a little about encryption; although I think he did not work long for the government. He told me that, although in 1959 he had discovered " multidimensional correlation attacks on nonlinear sequences ", at the same time he " carefully avoided allegations that the program was for cryptanalysis ." The fact is that rule 30 for cellular automata (and, perhaps, also shift registers with non-linear feedback) can be good cryptosystems - although due to the fact that they seem equivalent to shift registers with linear feedback (and this is not the case). ), they were never used as much as possible.

Being an enthusiast, over the past few decades I have tried to study all the predecessors of my work on one-dimensional cellular automata. Two-dimensional cellular automata have been little studied, but in the case of one-dimensional, only one purely theoretical work was found. I think that of all that I saw, the shift registers with Solomon Golomb’s non-linear feedback were closest to what I eventually did a quarter of a century later.

Poliomino

Hearing the name " Golomb ", many will recall the shift registers. However, the majority will remember poliomino . Sol did not invent polynomial, although he coined this name. He made systematic what used to appear only in separate puzzles.

The main question, in the answer to which Sol was interested, is how polynomials can be organized, covering some area. Sometimes it's pretty obvious, and sometimes it's pretty hard. His first article on poliomino was published by Sol in 1954, but Martin Gardner made poliomino in 1957 really popular (he led a column on math games in Scientific American ). As Saul explained in the preface to his book of 1964, as a result, he received "a steady stream of correspondents from around the world and from all walks of life: the chairmen of the boards of directors of leading universities, residents of unknown monasteries, prisoners from famous prisons ... ".

Gaming companies also noticed new puzzles, and over the course of a few months, headlines like " new sensational puzzles " appeared, followed by decades of other puzzles and games based on polynomino (no, an ominous bald guy doesn't look like Sola):

Saul published articles about poliomino for another 50 years after the first publication. In 1961, he presented the options of dividing into small parts " rep-tiles ", with which you can create fractal ("Infin-tile") patterns. But almost everything Sol did with poliomino included solving specific problems.

I am not interested in the specifics of poliomino; I am interested in related phenomena of a more general nature . It seems that it is easy to decide whether it is possible to “tile” the whole plane with a few simple forms. But in the case of polynomials (as well as all the games and puzzles based on them) it becomes clear that everything is not so simple. And indeed - in the 1960s, it was proved that this problem was theoretically unsolvable .

If we are only interested in a limited area, then, in principle, you can simply list all the possible arrangements of the figures, and then see if they are arranged in the right way. However, if we are interested in infinity, then this can not be done. Maybe someone will find the option of successfully placing a million pieces, but there is no guarantee that this result can be extended further.

It turns out that it may look like a working Turing machine - or a cellular automaton. You start with a line of tiles. Then the question of whether infinite paving is possible is equivalent to the question of whether the installation is possible for a Turing machine, which will enable it to not stop. The fact is that if a Turing machine is universal (that is, it can be programmed to perform any possible calculations), then the problem of stopping for it can be insoluble, which means that the problem of tiling will also be insoluble.

Of course, it depends on the original set of forms. The question is how complex the forms must be in order to encode universal calculations and lead to the unsolvable problem of tiling. Solomon Golomb knew about the literature on this subject, but was not particularly interested in it.

It is known that complex and carefully designed sets of polyominoes actually support universal calculations. But what about a simple set? Is it simple enough to accidentally stumble upon it? If you look at all the systems that I studied, then the simplest set really turns out to be simple. However, it is difficult to find.

A much simpler task is to find polynomials that successfully fill the planes, albeit only non-periodically. Roger Penrose in 1994 found a suitable example. In my book, a new kind of science, I gave a slightly simpler example with 3 polyominoes:

Rest of the story

Sol was a little over thirty when he achieved significant success in the field of shift registers and polynomino ... He was a very active person. He wrote several hundred articles , some of which expanded his earlier works, some were answers to the questions he was asked, and some were written, it seems, just for fun — to find out interesting things about numbers, sequences, cryptosystems, etc. d.

Shift and polynomial registers are voluminous topics (they are even listed in separate categories in the AMS classification ). In recent decades, they both received a new round of development, when computer experiments began to be carried out on their basis; Sol also took an active part in them. However, many questions remain unanswered. And if large Hadamard matrices can be found for linear-shift shift registers, even now, little is known about shift registers with non-linear feedback, not to mention all non-periodic and other exotic polynomials.

Sol has always been interested in puzzles, both in math and in words. For some time, he led a column of puzzles for the Los Angeles Times , and for 32 years wrote the Golomite of Golomb in the journal for graduates of John Hopkins. He participated in the testing of MegaIQ and won a trip to the White House, when he and his boss entered the top five in the country.

He put tremendous efforts into his work at the university: not only he taught students and supervised graduate students and ascended the administrative ladder (president of the university council, vice-rector for research, etc.), but also expressed his opinion about managing the university as a whole (for example, wrote an article entitled "Consulting at the Faculty: remove or leave?" ; The answer is: no, this is good for the university!). At the University of Southern California, he was engaged in headhunting, and during his work there, he helped the university rise from obscurity to the top of the ranking of educational programs.

And then there was consulting. Saul was meticulous and did not disclose what he was doing for government organizations. In the late 60s, disappointed that everyone except him was engaged in selling polynom-based games, Saul founded a company called Recreational Technology, Inc. Things were not going well, but Saul met Alvin Berlekamp , a professor from Berkeley who was fond of coding theories and puzzles. Subsequently, they founded Cyclotomics (in honor of the cyclotomic polynomials of the type x n - 1), which was eventually sold to Kodak for a lump sum (Berlekamp also created an algorithmic trading system, which he then sold to Jim Simons and which became the starting point for Renaissance Technologies - one of the largest hedge funds to date).

More than 10,000 patents are somehow connected with the work of Saul, but Sol himself received only one patent for quasigroup -based cryptosystems - and I think he did little to commercialize his work.

For many years, Sol worked with the Technion - an Israeli Institute of Technology. He spoke of himself as a " non-religious orthodox Jew, " but sometimes he conducted seminars on the Book of Genesis for newbies, and also worked on deciphering parts of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Qumran manuscripts).

Sol and his wife traveled a lot, but the “center of the world” for Sol was definitely his office in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California, and the house where he and his wife lived for almost 60 years. He was always surrounded by friends and students. And he had a family. His daughter Astrid played the role of a student in a play about Richard Feynman (she posed for him), and in the novel of my friend as one of the characters. Beatrice dedicated her career to applying mathematical level of accuracy to various types of medical indications and diagnostics (diseases associated with the Gulf War, effects of statins, attacks of hiccups, etc.). I even made a small contribution to the life of Beatrice, introducing her to the man who then became her husband - Terry Sejnovski , one of the founders of modern computational neuroscience.

It seemed that Saul was involved in a lot of events, even if he didn’t get too far from the details. From time to time I wanted to talk to him about science and mathematics, but it was more interesting for him to tell stories (often very fascinating) both about individuals and organizations (“ Can you believe that [in 1985] after a long absence at conferences, Claude Shannon just appeared without warning at the bar at the annual conference on information theory? ";" do you know how much they had to pay to the head of the California Institute of Technology to get him to go to Saudi Arabia ? ", etc.) .

Looking back, I understand that I would like to interest Saul in solving some of the mathematical questions raised in my work. I think that I did not understand to what extent he liked to solve problems proposed by other people. Despite a significant contribution to the development of the infrastructure of the computing world, Sol himself never seriously used computers. He was very proud that he could easily perform calculations in his mind. Until the age of 70, he did not use e-mail and never used a computer at home, although he had a mobile phone (he didn’t receive regular e-mail from him. I mentioned that I studied the history of Ada Lovelace about a year ago; He replied: " The story of Ada Lovelace as a Babbage programmer is so widespread that everyone seems to accept it as a fact, but I have never seen sources on this subject. ").

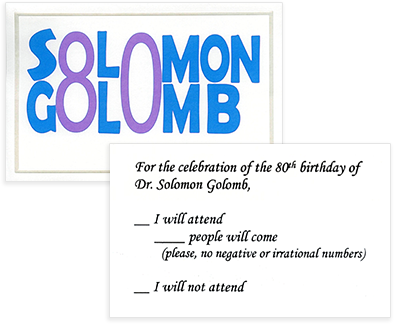

A few years ago, Sola’s daughters organized a party on the occasion of his 80th birthday and created such interesting invitations:

Saul had certain health problems, although it seemed that this did not really reflect on his rhythm of life. His wife's health has deteriorated, and in the past few weeks, quite dramatically. On Friday, Sol, as usual, went to his office, and on Saturday night he died in a dream. His wife, Bo, survived him for only two weeks and died just two days before the 60th anniversary of their wedding.

Although Saul is gone, his work lives in octillion bits in the digital world.

Goodbye, Sol. And from all of us - thanks.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/309232/

All Articles