Dagaz: In the wilds of notations

Spit in the eyes of someone who will say that you can hug the immense!

Spit in the eyes of someone who will say that you can hug the immense! ...

Zeal overcomes everything!

Kozma Prutkov " Thoughts and Aphorisms "

People constantly invent something. After the invention of chess , several thousand more similar games were developed. Initially, according to the old habit left from the time of composing ancient myths, chimeras were created, combining the qualities of two or more chess pieces, but later the authors' imagination got stronger and began to produce more interesting variants. In order not to get entangled in all this zoo, some kind of system was needed, the ability to classify new figures. And she arose. Actually, I know two of them . Unfortunately, both of them do not work.

A variety of chess options have always been the focus of attention of the chess community. In specialized publications you can find descriptions of new games, analyzes of games, as well as articles on the history of chess. Attempts to systematize the rules have never been considered as something extraordinary. Rather, it is a vital necessity. The basis of such classifications was the division of all chess pieces into two large classes: leapers and riders .

')

Leaper -s are jumping figures (for example, a chess "Horse" is (1,2) -leaper ), moving by the number of fields indicated in brackets, not paying attention to the figures along the way. Figures moving one field can also be considered leaper -s ( Ferz from Shatranj is (1,1) -leaper ), but since they move to a neighboring field, only 0 figures can jump over (everything is legal). With a great desire, to the same class can be attributed, and chess " Pawn ", but usually do not. Most Orthodox do not even consider it a figure.

Rooks , elephants and queens fall into another category of pieces. These are rider s - figures moving in a straight line through an arbitrary number of empty fields (Rook - (1,0) -rider ). There are "jumping" rider- s, such as Nightrider (derived from a chess knight), but they, along their own path, can only move along empty fields. The proposed classification was considered reasonable and convenient until there were figures that do not fit into it. So appeared the Hopper- s and Locust- s. This did not solve the problem, since there were hundreds of figures that are neither.

Parlett's movement notation

The first large-scale attempt, to restore order in this zoo, made, apparently, David Parlett . In his book, The Oxford History of Board Games , he used the notation of his own invention to classify the various pieces used in numerous variations of chess games.

Parlett

Distance:

Direction:

Grouping:

This set of rules is sufficient to describe simple cases such as King ( 1 * ) or Rook ( nX ) in classical Chess. But already in the case of the Chess Horse , difficulties begin. How to express the fact that this figure can “jump over” through other figures? With Pawn, too, everything is not easy. This is the only figure in Chess performing the "quiet" and "shock" moves in different ways. Accordingly, special characters are required to allow these situations to be separated. There was a need to expand the notation:

Terms of progress:

Types of moves:

Additional grouping types:

- 1 - move to the adjacent field

- 2 - in one field

- n - for an arbitrary number of fields (like Rook or Elephant)

Direction:

- * - Moving in all (eight) directions

- + - According to orthogonal lines (verticals and horizontals)

- > - Forward vertically

- < - Back vertically

- <> - Forward and back vertically

- = - Horizontally (right or left)

- > = - Horizontally or vertically forward

- <= - Horizontally or vertically back

- X - Diagonally

- X> - Forward diagonally

- X < - Diagonally back

Grouping:

- / - Sequential execution of two orthogonal displacements

- & - Repeat movement in the same direction.

- . - performing one action after another

This set of rules is sufficient to describe simple cases such as King ( 1 * ) or Rook ( nX ) in classical Chess. But already in the case of the Chess Horse , difficulties begin. How to express the fact that this figure can “jump over” through other figures? With Pawn, too, everything is not easy. This is the only figure in Chess performing the "quiet" and "shock" moves in different ways. Accordingly, special characters are required to allow these situations to be separated. There was a need to expand the notation:

Terms of progress:

- i - The first move by the figure (for example, the Pawn move from the initial position through one field)

- c - Execution of capture (shock stroke)

- o - Stroke without capture (silent)

Types of moves:

- ~ - Skipping over other shapes

- ^ - Taking the sprung shape (as in checkers )

Additional grouping types:

- , - Separator of move variants (for example, for Pawn three possible moves are determined)

- - - Determining the range of possible movement of the figure

- King: 1 *

- Queen: n *

- Elephant: nX

- Rook: n +

- Horse: ~ 1/2

- Pawn: o1>, c1X>, oi2>

What can be said about this notation? First of all, it is not very obvious and (which is much worse) is not at all universal. Yes, we have provided a special symbol for “jumping” figures and for taking when “jumping”, as in checkers ( cn (^ 2X>), o1X> ), but we completely forgot about such an important class of figures as Hoppers .

As a result, all sorts of "guns" (for example, from Xiangqi and Janggi ) remained "behind" our description. Moreover, even chess pieces are described inaccurately. Yes, for the pawn, the possibility of “jumping” through an empty field from the initial position ( oi2> ) is described, but where is the description of the capture on the aisle ? Where is the castling notation performed by the King? If any possibility is difficult to describe, it does not mean that it is not necessary to describe it!

Ralph Betza's funny notation

Ralph Betza - personality, in the world of chess, also known. In addition to the serious hobby of classic chess, he is known as a developer of more than 40 highly original variations of this game, such as " Chess with different armies " or " The Way of the Knight ". Acutely aware of the need for a classification system for chess pieces, Ralph proposed his own version of the notation . The system proposed by him has become, in fact, the generally accepted standard used to describe the capabilities of chess pieces.

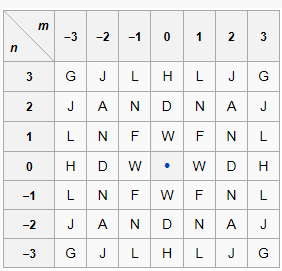

Betza The description is based on capital letters of the Latin alphabet. Each of them determines the course of the fundamental leaper:

The description is based on capital letters of the Latin alphabet. Each of them determines the course of the fundamental leaper:

W - Wazir (0,1) -leaper

F - Fers (1,1) -leaper ("Queen" from Shatrange )

D - Dabbaba (0,2) -leaper

N - Knight (1,2) -leaper (the well-known chess "Horse")

A - Alfil (2,2) -leaper

H - Threeleaper (0,3) -leaper

C - Camel (1,3) -leaper

J - Zebra (2,3) -leaper

G - Tripper (3,3) -leaper

For the most common shapes, abbreviations are introduced. So the chess “King” ( K = FW ) combines the moves of the Fers and Wazir pieces. A rider is obtained from a leaper by doubling a capital letter. Chess "Elephant" ( B = FF ) is nothing more than a rider , derived from the Fers figure, just like the Rook ( R = WW ) is based on the Wazir figure. Chess "Queen" ( Q = BR ) combines the moves of these two figures. Of course, this is not enough. For the "Pawn" (the most difficult figure) it is necessary to set modifiers:

In addition to modifiers, figures can be used in Betza notation. W5 , for example, defines a limited range , allowing you to move orthogonally, by no more than 5 steps. In some cases, square brackets can be used to group "atoms". For example, t [WB] (or 1 + .nX , in the Parlett-a notation) describes the “Aanca” shape, which is moved one field orthogonally and, subsequently, an arbitrary number of fields diagonally.

W - Wazir (0,1) -leaper

F - Fers (1,1) -leaper ("Queen" from Shatrange )

D - Dabbaba (0,2) -leaper

N - Knight (1,2) -leaper (the well-known chess "Horse")

A - Alfil (2,2) -leaper

H - Threeleaper (0,3) -leaper

C - Camel (1,3) -leaper

J - Zebra (2,3) -leaper

G - Tripper (3,3) -leaper

For the most common shapes, abbreviations are introduced. So the chess “King” ( K = FW ) combines the moves of the Fers and Wazir pieces. A rider is obtained from a leaper by doubling a capital letter. Chess "Elephant" ( B = FF ) is nothing more than a rider , derived from the Fers figure, just like the Rook ( R = WW ) is based on the Wazir figure. Chess "Queen" ( Q = BR ) combines the moves of these two figures. Of course, this is not enough. For the "Pawn" (the most difficult figure) it is necessary to set modifiers:

- f - Forward

- b - Backward movement

- v - Short fb modifier entry

- l - Move left

- r - move right

- s - rl modifier short entry

- t - performing one action after another

- with - Taking

- m - "Silent" move

In addition to modifiers, figures can be used in Betza notation. W5 , for example, defines a limited range , allowing you to move orthogonally, by no more than 5 steps. In some cases, square brackets can be used to group "atoms". For example, t [WB] (or 1 + .nX , in the Parlett-a notation) describes the “Aanca” shape, which is moved one field orthogonally and, subsequently, an arbitrary number of fields diagonally.

- King: K = WF

- Queen: Q = RB

- Elephant: B = FF

- Rook: R = WW

- Horse: N

- Pawn: mfWcfF

All this is fine, but the “Pawn” should be able to walk through one field from the starting position! Need more modifiers for Betza notation!

Betza (continued)

What does the " h " modifier mean? To understand this, you need to remember one of the figures of " Japanese chess ". The horse is “jumping” in them, as in classical chess, but it goes only forward, only two fields. How to express this through Betza notation? fN is a good attempt, but, moving "forward", a horse, generally speaking, can get on 4, not on 2 fields! The modifier h is designed to "settle" this situation:

I must say that when using Parlett's notation, the Japanese horse looks no better: (~ 1/2)> (narrow) .

- g - Grasshopper

- p - "Cannon" (this is from " Chinese chess ")

- h - Funny modifier, which I’ll tell about below

- j - Mandatory "jumping" of the figure

- n - Movement without "jumping" through the figures

- o - Movement on a cylindrical board

- z - Zigzag shape movement (another funny modifier)

What does the " h " modifier mean? To understand this, you need to remember one of the figures of " Japanese chess ". The horse is “jumping” in them, as in classical chess, but it goes only forward, only two fields. How to express this through Betza notation? fN is a good attempt, but, moving "forward", a horse, generally speaking, can get on 4, not on 2 fields! The modifier h is designed to "settle" this situation:

- ff - “forward-forward” movement (as “Horse” in Shogi)

- fs - Forward-to-side motion (from the e4 field one can get to c5 or g5 )

- fh - Moving Forward (all four sides)

I must say that when using Parlett's notation, the Japanese horse looks no better: (~ 1/2)> (narrow) .

- Pawn: mfWcfFimfW2

It does not describe the " taking on the aisle, " but we will not be too petty. Of course, this notation is not universal! Here is what the author writes about this:

The notation is not universal or perfect yet. It can be used to make it so that it’s possible to make it. My notation has no way to describe such a piece.

However, such horrors as “Elephant” with “variable turn geometry” are not required at all to put Betza notation to a standstill. There are a lot of other funny figures that have been used in numerous versions of Shogi for centuries. Begin, of course, should be with Chu Shogi and her "Lion":

This figure makes as if two moves (both on the same field in any direction, as the "King"). Thus, the “Lion” can eat two figures per turn or perform an even more cunning acrobatic number - eat the figure next to it and, by the second move, return to its place. Such a move, in various “Shogi variants”, is of such fundamental importance that it is given a proper name - igui . And this is not the most exotic application of the “second move” concept:

These are three figures from Ko Shogi . Cavalry (騎 総 kisō) is very similar to the figure of "Lion", but uses the move of the chess "Horse", while moving in the "same" direction. Winged horse (天馬 temba) - a stronger figure, continuing to move in any direction accessible to the “Horse”. Twelve-mile fog (五里 霧) looks simpler, moving twice like Alibaba ( AD ), but after each turn, it can “kill” the enemy figure that happened to be next to him with igui . If these examples are not enough, there will be more:

Roaming assault (招 揺 shōyō) - "War chariot", moving in five (or less) fields in a straight line, killing all the enemy pieces that fall into the path. Thunderclap (霹靂 hekireki) makes all the same five orthogonal moves, but randomly changing direction! And do not think that this is found only in Ko Shogi! Dai dai shogi , Tenjiku shogi , Taikyoku shogi - all these games use similar figures. HG Muller , the developer of the wonderful WinBoard / XBoard chess program, offered another fun modifier to solve this problem.

The modifier " a " means the execution of the "second move", which allows to describe the move of the "Lion" as aK (double move "The King"). As usual, additional modifiers allow you to describe more complex moves. So, for example, in the expanded notation of Betza, the move of the piece from “Checkers” looks like: fmF (fcafmF) . You can try to decipher it yourself. It is this notation that is used when describing figures in "historical" versions of Shogi:

- Cavalry: [NaffN] [xN]

- Winged horse: aN

- Twelve-mile fog: a [DA] acxK

- Roaming assault: Wa5fW

- Thunderclap: a! 5W

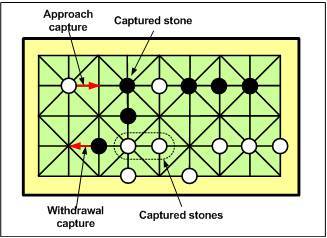

Do you think the Betza notation has become universal? Then try to describe, with its help, this game:

So…

If you have a problem and you want to use regular expressions ...

Understand me correctly, I'm not looking for complexity for the sake of complexity! I just do not like the fact that existing notations are non-constructive. In fact, what do we do when we discover a new type of shape? We add a new letter! For example, no need to go far. Here is what HG Muller writes about castling:

This is not the original atom atom but many extensions. As such, any repetition of it, like O2, would be pointless, like any modifier prefixes. I therefore propose to use O + number as a shorthand for (conventional) castling. (After all, casting in PGN is denoted as OO or OOO.) King moves. He ends up with a little bit of it. You can’t be empty. King would be FIDE: WFisO2

Reserving a single letter for such a private thing as castling, to me personally, seems very wasteful! Following this path, we will begin to reserve all new and new letters for all specific moves! For example, in Jetan- e "Princess", once per game, has the right to jump onto any free board field that is not under combat. This move is not similar to castling. So you need a new letter? And what to do when all the letters end? And this is not to mention the fact that at the output we have not quite obvious, not universal and, most importantly, redundant notation:

- g - Grasshopper

- p - "Cannon" from " Chinese chess "

- j - Mandatory "jumping" of the figure

- ...

Grasshopper is almost the same as the Cannon (in any case, Korean)! Why waste another letter on him? And his behavior is directly connected with “jumping over” the figures ( j )! With the Parlett notation, the same story: ' ~ ' - jumping over the figures, ' ^ ' - taking the sprung figure, but we generally forgot about the hopper- s! Returning to Fanorone . The whole problem lies in its specific way of taking:

This is not a chess and checkers take. Given the limited size of the board, such a move can be described using the ' a ' modifier for Betza notation, but the description will be very cumbersome! We'll have to describe the movement of the figure beyond the target field (with the capture of enemy figures along the way), and then the return, for the chain of each length and for all eight directions! And this is not to mention the fact that all these eight directions are not available in all the fields of Fanorona. But Fanorona is not some new-fashioned invention! In Madagascar, this game has been played since 1600.

(*)[p]|((\1[ex])*;~1(~1[ex])*) It looks like a complete abracadabra and is somewhat similar to regular expressions . In general, this is not an accident. Regular expressions were invented to describe finite automata , but what is a game board, with a moving figure on it, but a finite state machine? Consider the component parts in more detail:

Dagaz

In fact, the entire expression is an enumeration of actions performed sequentially or alternatively. Sequential actions are separated by a comma (' , '), and alternatives - a semicolon (' ; '). Actions can be grouped by parentheses. Since actions change the state of the board and the figures, it is important that the comma determines the order in which the actions are performed. Successfully performing all the actions listed separated by commas (in most cases it can be omitted), in the order specified, we generate a possible move.

The alternative is a bit more complicated. Two (or more) alternatives start from the same initial state and work independently of each other. We reach the goal if we manage to execute any of the alternatives. For simplicity, we can assume that the comma links actions as ' and ', and the semicolon - as ' or '. In principle, these two actions are already enough, but in order to shorten the description, we will need quantifiers:

Just like in regular expressions. Of course, we also define familiar abbreviations:

Now let's talk about actions. The obvious action is to move in one of the directions of the board. Traditionally, the designations of the cardinal directions are used: ' N ', ' S ', ' W ', ' E ' - for orthogonal and ' NW ', ' NE ', ' SW ', ' SE ' - for diagonal directions, but, for reasons , which I will talk about below, I would not like to use two-letter notation. Instead of them, I decided to use ' M ', ' O ', ' R ' and ' T ', in the same way as it is done in the project " LUDÆ ". In this way:

Designations of generalized directions conflict with quantifiers, but this collision is easy to resolve. The move action can always be bracketed, and the quantifier can never immediately follow the opening bracket. It should be noted that the definition of directions is closely related to the description of the board. It looks like this:

If the shape is set to “in any direction” (' * '), and the position at which it is located, defines only orthogonal directions - the shape can move only orthogonally. Why don't I want to use two-letter symbols? It's simple - if I list several alternative directions, I have to separate them with a semicolon (for example, the movement of a non-transformed figure in Turkish Checkers - W; N; E ), but since such a record would occur often, I would like omit the semicolons, for greater brevity (simply write - WNE ). I would not like to have conflicts with the two-letter designations of directions in these cases.

Other actions:

About variables it is worth telling more. It is tempting to describe the “Rook” move as follows: NEWS + (or even just: ++ ), but this will be an obvious mistake. In fact, with this description we say that the “Rook” is orthogonal, one or more steps, but nowhere do we mention that the movement must take place in the same direction! This is very similar to the course of the previously mentioned Thunderclap figure, but without any limitation of the stroke range.

The choice of direction must be made once per turn, which means that the chosen direction must be fixed in a variable: (+) \ 1 * . This description is better, but it is not entirely correct. The rook can move in a straight line, up to the first enemy figure, but only along empty fields. In order for the “Rook” not to pass through other figures, it is necessary to clarify the description: (+) ([p] \ 1) * . The letter in square brackets here is a special check that the field on which we are empty (if this is not the case, the course generation is interrupted). This is one of the standard actions defined by the specification:

In addition to the above, square brackets allow the specification to be extended by inserting references to handlers in a universal programming language (for example, JavaScript). Specifying the number in square brackets, we say that a special handler must be called at this place to perform actions that are impossible or impractical to describe the specification language (as I mentioned above, no one can grasp the immense). A good example of a game that illustrates the need for such extensions can be Ritmomachia .

Another important feature is navigation within square brackets. For example, if we need to perform a capture without moving the figure itself, it is not necessary to write something like N [x] S , the record of the form [x> N] would also be quite correct.

The alternative is a bit more complicated. Two (or more) alternatives start from the same initial state and work independently of each other. We reach the goal if we manage to execute any of the alternatives. For simplicity, we can assume that the comma links actions as ' and ', and the semicolon - as ' or '. In principle, these two actions are already enough, but in order to shorten the description, we will need quantifiers:

- {n, m} - Repeat action from n to m times (n <m)

- {n} - Repeat the action n times exactly

- {n,} - At least n times

- {, m} - Not more than m times

Just like in regular expressions. Of course, we also define familiar abbreviations:

- ? - {0,1}

- * - {0,}

- + - {1,}

Now let's talk about actions. The obvious action is to move in one of the directions of the board. Traditionally, the designations of the cardinal directions are used: ' N ', ' S ', ' W ', ' E ' - for orthogonal and ' NW ', ' NE ', ' SW ', ' SE ' - for diagonal directions, but, for reasons , which I will talk about below, I would not like to use two-letter notation. Instead of them, I decided to use ' M ', ' O ', ' R ' and ' T ', in the same way as it is done in the project " LUDÆ ". In this way:

- N - Server

- S - South

- W - West

- E - East

- M - Northwest

- O - Northeast

- R - Southwest

- T - Southeast

- U - Up (tell about it below)

- D - Down

- + - Orthogonal (similar to Parlett and LUDÆ)

- X - Diagonally

- * - In all (standard) directions

Designations of generalized directions conflict with quantifiers, but this collision is easy to resolve. The move action can always be bracketed, and the quantifier can never immediately follow the opening bracket. It should be noted that the definition of directions is closely related to the description of the board. It looks like this:

Fanorona Board

- fanorona-9x5 grid: ai x 5-1 N = (0, -1) E = (1, 0) S = (0, 1) W = (-1, 0) O = a3>b4>c5,a1>b2>c3>d4>e5,c1>d2>e3>f4>g5,e1>f2>g3>h4>i5,g1>h2>i3 T = a3>b2>c1,a5>b4>c3>d2>e1,c5>d4>e3>f2>g1,e5>f4>g3>h2>i1,g5>h4>i3 R = c5>b4>a3,e5>d4>c3>b2>a1,g5>f4>e3>d2>c1,i5>h4>g3>f2>e1,i3>h2>g1 M = c1>b2>a3,e1>d2>c3>b4>a5,g1>f2>e3>d4>c5,i1>h2>g3>f4>e5,i3>h4>g5 If the shape is set to “in any direction” (' * '), and the position at which it is located, defines only orthogonal directions - the shape can move only orthogonally. Why don't I want to use two-letter symbols? It's simple - if I list several alternative directions, I have to separate them with a semicolon (for example, the movement of a non-transformed figure in Turkish Checkers - W; N; E ), but since such a record would occur often, I would like omit the semicolons, for greater brevity (simply write - WNE ). I would not like to have conflicts with the two-letter designations of directions in these cases.

Other actions:

- \ 1 , ... \ 9 - Moving in the direction previously captured in the variable

- ~ 1 , ... ~ 9 - Moving in the opposite direction of the captured

- | - Setting the figure on the board (all subsequent movements are performed without a figure)

- [...] - Special actions, checks and more

About variables it is worth telling more. It is tempting to describe the “Rook” move as follows: NEWS + (or even just: ++ ), but this will be an obvious mistake. In fact, with this description we say that the “Rook” is orthogonal, one or more steps, but nowhere do we mention that the movement must take place in the same direction! This is very similar to the course of the previously mentioned Thunderclap figure, but without any limitation of the stroke range.

The choice of direction must be made once per turn, which means that the chosen direction must be fixed in a variable: (+) \ 1 * . This description is better, but it is not entirely correct. The rook can move in a straight line, up to the first enemy figure, but only along empty fields. In order for the “Rook” not to pass through other figures, it is necessary to clarify the description: (+) ([p] \ 1) * . The letter in square brackets here is a special check that the field on which we are empty (if this is not the case, the course generation is interrupted). This is one of the standard actions defined by the specification:

- [p] - Is the field empty?

- [P] - The field is not empty?

- [e] - Enemy figure?

- [E] - Not an enemy figure?

- [f] - Friendly figure?

- [F] - Not a friendly figure?

- [a] - Field attacked?

- [A] - The field is not attacked?

- [s] - Is the field protected?

- [S] - The field is not protected?

- [o] - Is this type of move for the first time in a game?

- [m] - The figure moved?

- [M] - The shape did not move?

- [r] - The field was visited earlier, within the limits of the compound course?

- [R] - The field has not been visited before, within the compound course?

- [l] - The start field of the previous partial move?

- [t] - Field completion of the previous partial move?

- [x] - Taking a figure

In addition to the above, square brackets allow the specification to be extended by inserting references to handlers in a universal programming language (for example, JavaScript). Specifying the number in square brackets, we say that a special handler must be called at this place to perform actions that are impossible or impractical to describe the specification language (as I mentioned above, no one can grasp the immense). A good example of a game that illustrates the need for such extensions can be Ritmomachia .

Strictly speaking, I'm a little cunning

Defining the “Rook” turn as (+) ([p] \ 1) * I described how the figure moves across the field, but there is nothing about how the capture is performed. First, we should not be able to complete the move on the field occupied by the figure of our color. Further, if on the target field there is a figure of the enemy, it is required to take it and after that put your piece on the board: [F] [ex]? | . With the beginning of the turn, everything is not so simple either. Firstly, if we define the action of putting a figure on the board, the opposite to it should be determined, but the most important thing (and it is very easy to forget about it), we have the right to move along the field only the figures of its color (in “ Stavropol checkers ” this is not like that): [f] ^ .

These are really important points (if we are talking about universal notation), but repeating them in the description of almost every figure would be excessive. It is reasonable to make these postfix and prefix part of the description of the game board. This type of board ( default ) has two properties. Firstly (and this is the main thing) - each field of the board can contain no more than one figure. If we put another figure on a busy field, the figure standing on it earlier will automatically “climb”. The second rule is that the player has the right to move only his pieces (this is true for the vast majority of games).

This type of construction board is not the only possible. I can define at least two more types: stack (for games like " Puluk " or " Pillars ") and heap (for all sorts of " Mancal "). In the case of "pillar" games, the player has the right to move the "piles" of figures (provided that his piece is located at the top of the pile) and place the "piles" on top of each other. In mancalas, "figures" are placed on the field by an unordered "heap". The player takes the "heap" entirely and distributes it to other board fields. The shapes on the heap board are not necessarily the same type! There is at least one mancala for which this is not the case.

These are really important points (if we are talking about universal notation), but repeating them in the description of almost every figure would be excessive. It is reasonable to make these postfix and prefix part of the description of the game board. This type of board ( default ) has two properties. Firstly (and this is the main thing) - each field of the board can contain no more than one figure. If we put another figure on a busy field, the figure standing on it earlier will automatically “climb”. The second rule is that the player has the right to move only his pieces (this is true for the vast majority of games).

This type of construction board is not the only possible. I can define at least two more types: stack (for games like " Puluk " or " Pillars ") and heap (for all sorts of " Mancal "). In the case of "pillar" games, the player has the right to move the "piles" of figures (provided that his piece is located at the top of the pile) and place the "piles" on top of each other. In mancalas, "figures" are placed on the field by an unordered "heap". The player takes the "heap" entirely and distributes it to other board fields. The shapes on the heap board are not necessarily the same type! There is at least one mancala for which this is not the case.

Another important feature is navigation within square brackets. For example, if we need to perform a capture without moving the figure itself, it is not necessary to write something like N [x] S , the record of the form [x> N] would also be quite correct.

After all these necessary clarifications, I can “decipher” my notation of the course of the figures in Fanorone:

(*) # ( ) [p] # - | # ( (\1[ex])* # - ; # ~1 # ( ) (~1[ex])* # , ) Here, I deliberately omit the moments related to the description of the compound course (this is a separate and rather interesting topic ). Continuing the comparison of notations, I will give my description of the moves of chess pieces. In bold, the part of the description that Parlett and Betza were not even taken up (castling and taking "on the aisle") is highlighted :

- King: * [A] ; [MA] (E [p]) {2} [A] | E ^ [M] W {2}; [MA] (W [p]) {3} [A] | W ^ [M] E {2}

- Queen: (*) ([p] \ 1) *

- Elephant: (X) ([p] \ 1) *

- Rook: (+) ([p] \ 1) *

- Horse: N, OM; E, OT; S, TR; W, RM

- Pawn: N [p]; OM [e]; [M] (N [p]) {2} ; [(te, = Pawn, x)> E] O [l> N]; [(te, = Pawn , x)> W] M [l> N]

I would like to complete this narrative with the aphorism of Kozma Prutkov :

It happens that zeal overcomes and reason

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/309096/

All Articles