“My life through the prism of technology ...” - Stephen Wolfram

Today is the birthday of the creator of the systems Mathematica and Wolfram | Alpha, as well as the Wolfram Language - Stephen Wolfram. We hope that the translation of his speech at the Computer History Museum (Mountain View, California) will be interesting and useful for you. You will learn many unexpected, surprising facts from Stephen’s long professional and personal biography.

Translation of the post by Stephen Wolfram (Stephen Wolfram) " My Life in Technology — As Told at the Computer History Museum ".

I express my deep gratitude to Polina Sologub for assistance in translating and preparing the publication.

Usually I am interested in the future. However, the story, in my opinion, is interesting and informative, and I also study it a lot. Most often this is the life story of other people. But the Computer History Museum asked me to tell you today about my own life and the technologies I created. That's what I'm going to do.

')

Now a unique time has come for me - a lot of things over which I worked for more than 30 years began to bear fruit.

My focus is on the Wolfram Language - a new kind of language based on knowledge (in which a huge amount of knowledge is embedded - both about computing and about the world as a whole). Wolfram Language is as automated as possible so that the path from the idea to the actual implementation is as short as possible.

Today I want to talk about how I was going to create the system Mathematica and Wolfram | Alpha .

I will have to talk a lot about my own history: mainly about how I spent most of my life doing science and technology. When I look back, much of what happened seems inevitable and implacable. And something I did not expect.

But let me start at the beginning. I was born in London in 1959 - so yes: I am godlessly old (at least by my current standards). My father ran a small company (international trade in textiles) for almost 60 years, and also wrote several science fiction novels . My mother was a professor of philosophy at Oxford . The last time I was at the Stanford bookstore, I accidentally saw her textbook on philosophical logic.

You know, I remember when I was 5 or 6 years old, I missed a party with a bunch of adults, and here’s a very long conversation about some very respected philosopher from Oxford ended with the words: “the day will come, and this child will philosopher . " Well, they were right. It's pretty funny that this happens.

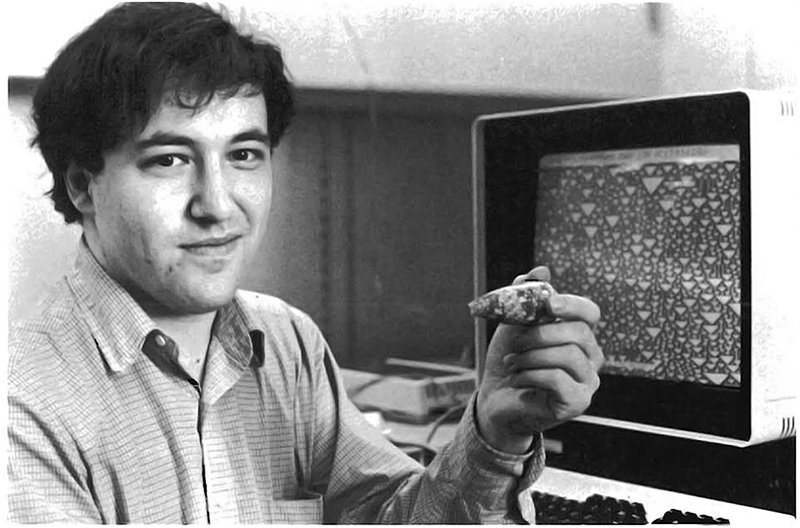

That's how I was then:

I went to elementary school in Oxford - to a place called The School of the Dragon (I guess this is probably the most famous elementary school in England). Wikipedia believes that the most famous people in my class right now are me and the actor Hugh Laurie .

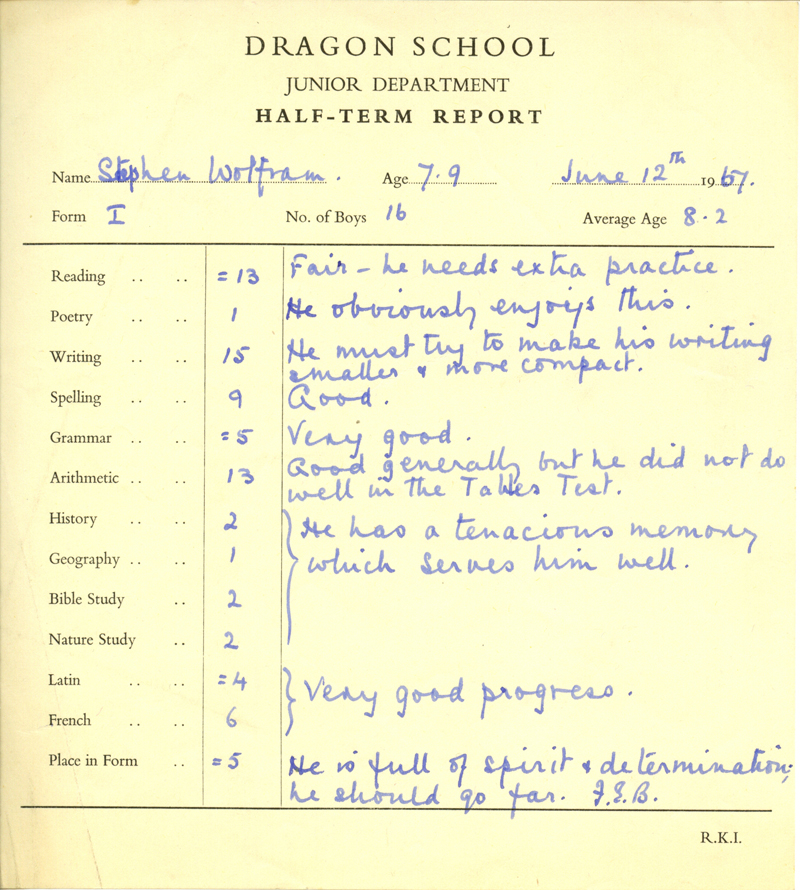

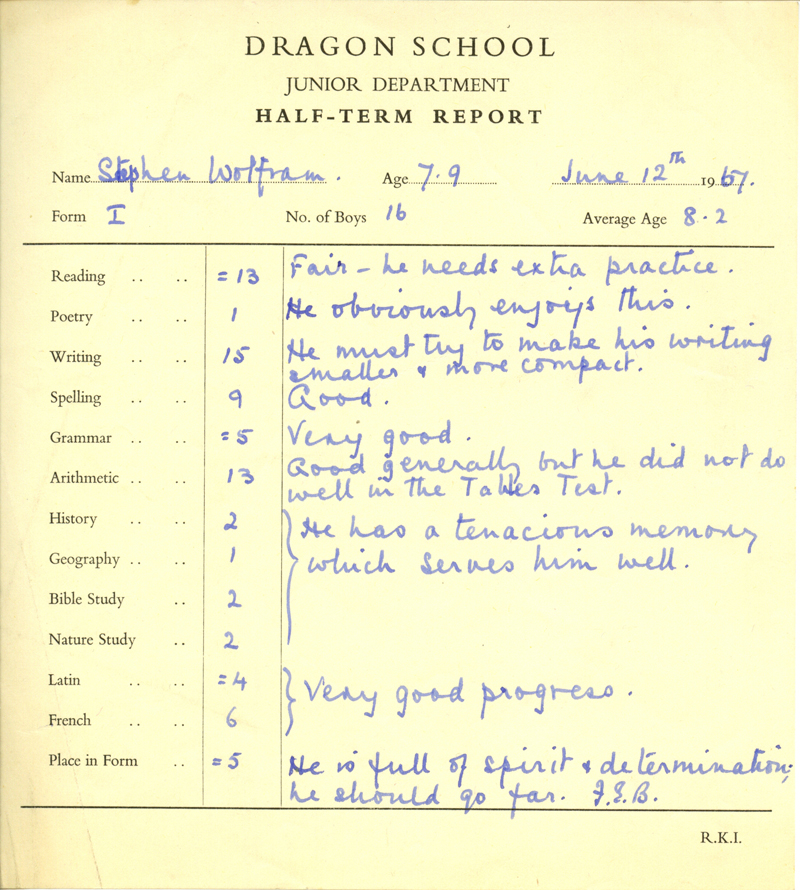

Here is one of my school reports (I was 7 years old). This is a class rating. So I excelled in poetry and geography, but not in mathematics (and yes, this is England, so we had the subject of “Bible study”). But at least it says: " he is full of spirit and determination; he must go far ... "

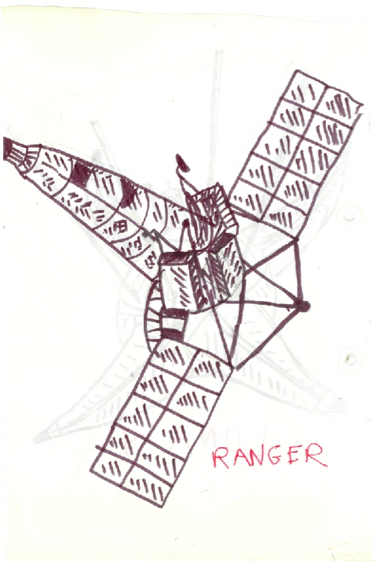

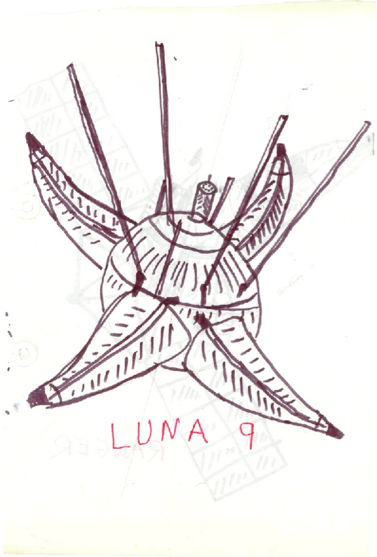

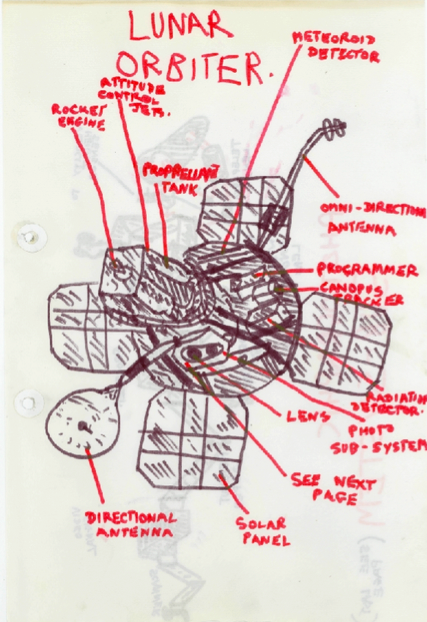

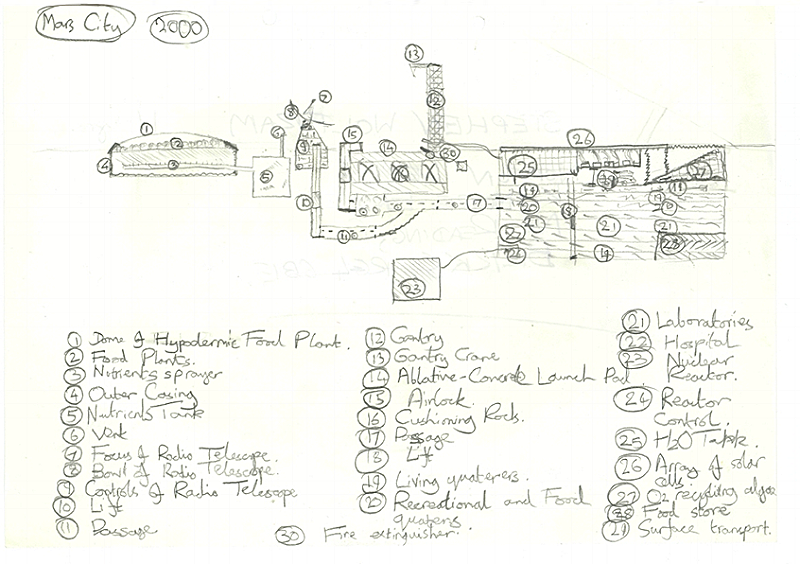

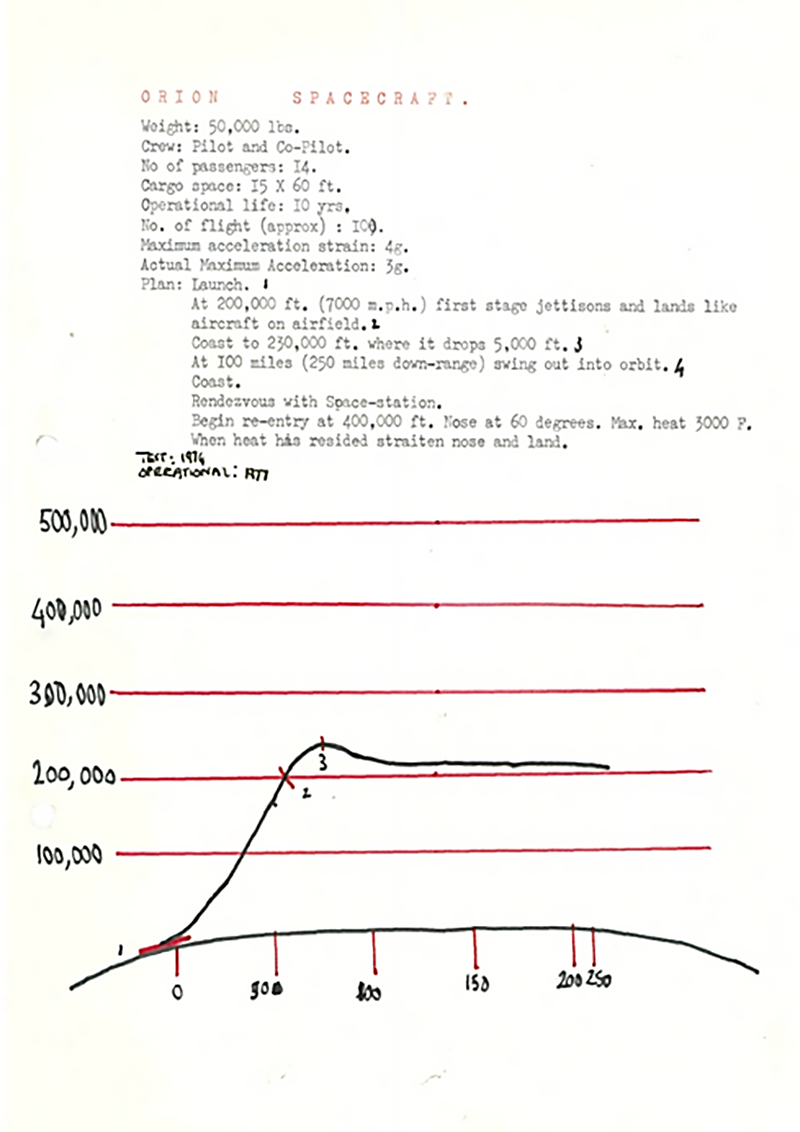

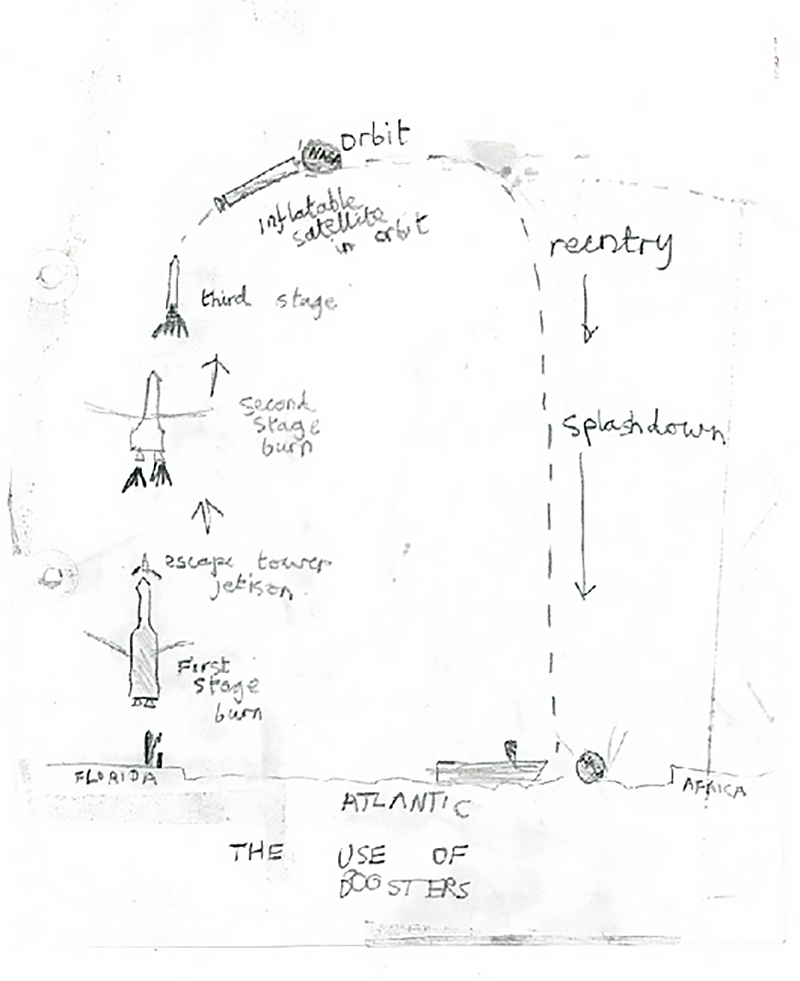

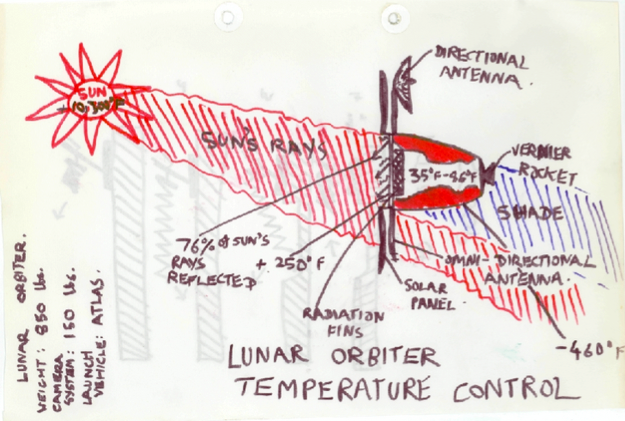

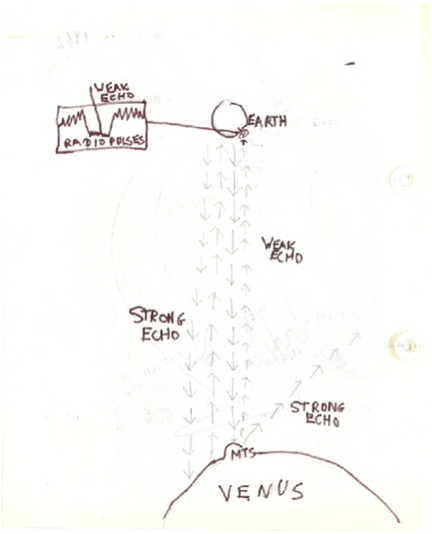

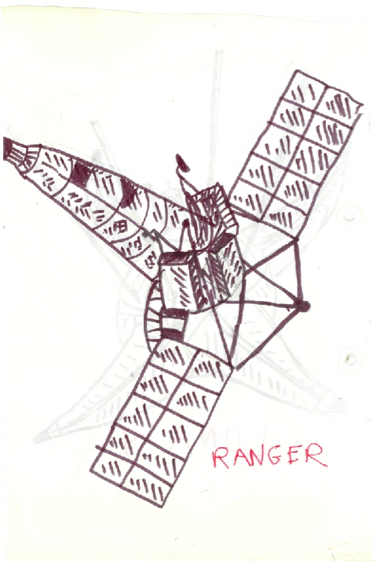

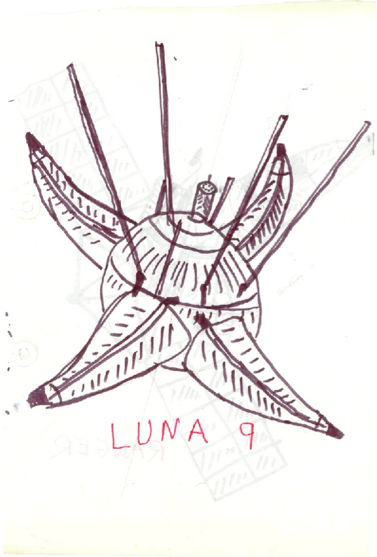

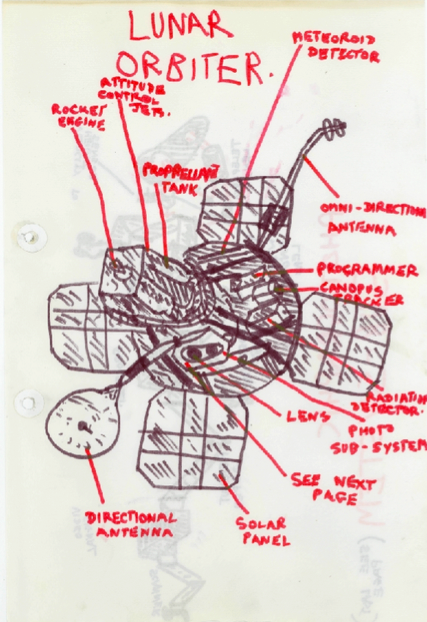

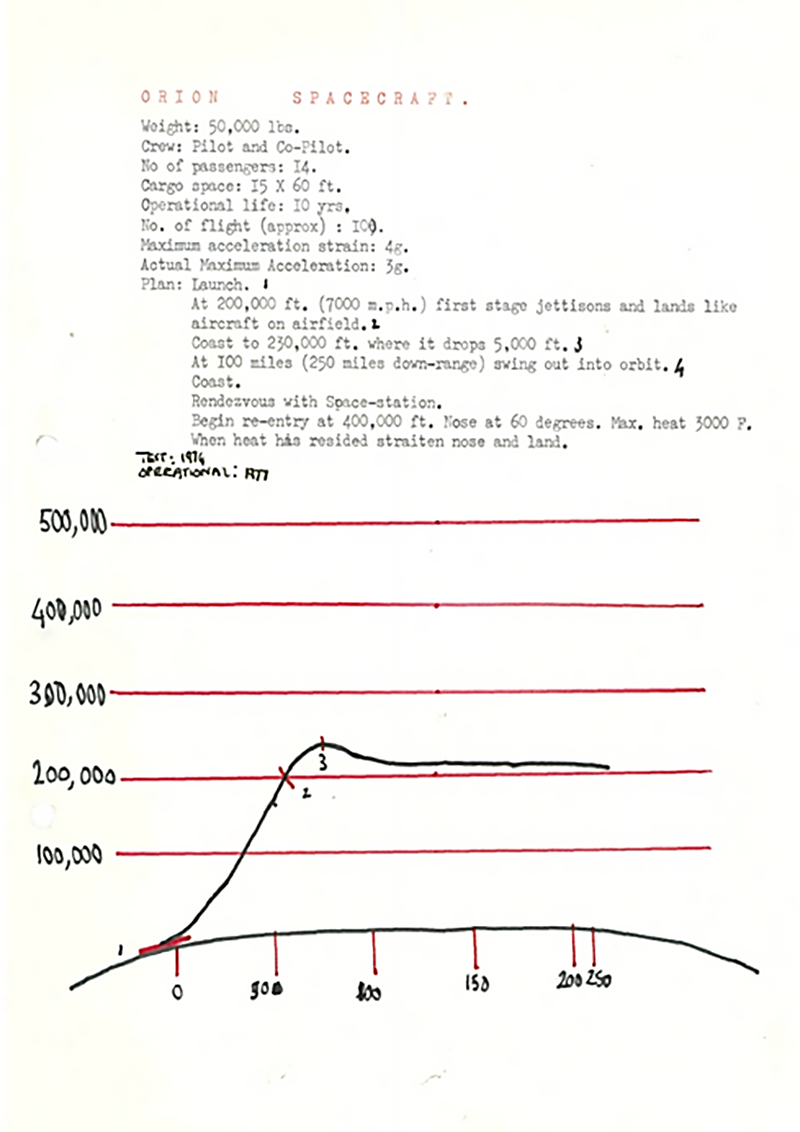

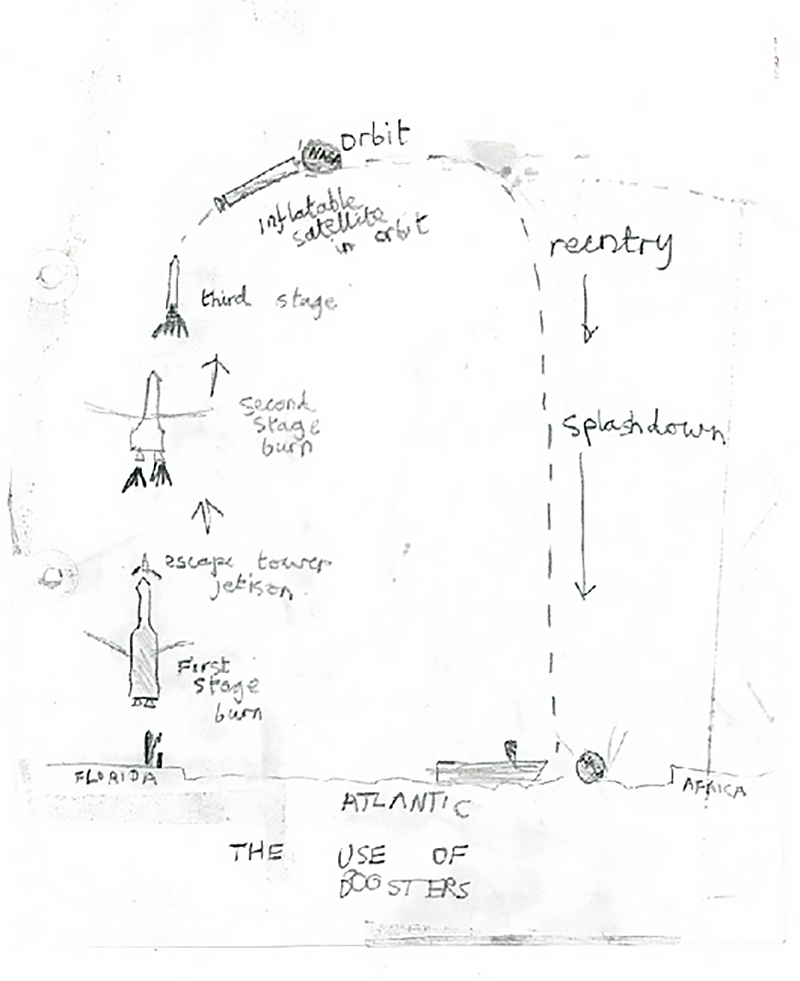

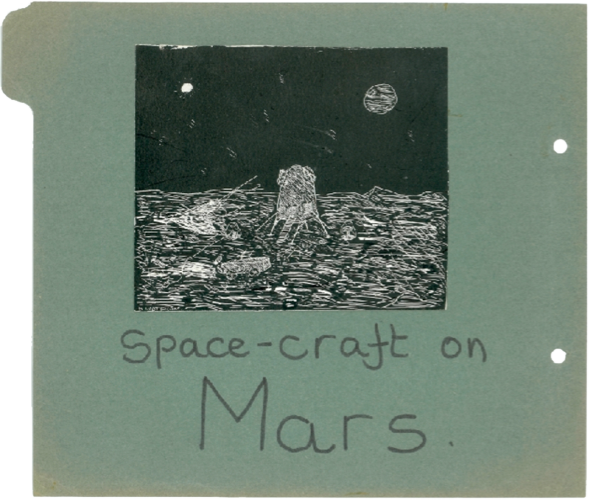

It was 1967, and I studied Latin and so on; but what I really liked was the future. At that time, the most future-oriented was the space program. And I became very interested and began to collect all the information I could find about each launched spacecraft, and the little notebooks, in which I saved all the information, put them together. And I found that even from England one could write to NASA and get all the material for free by mail.

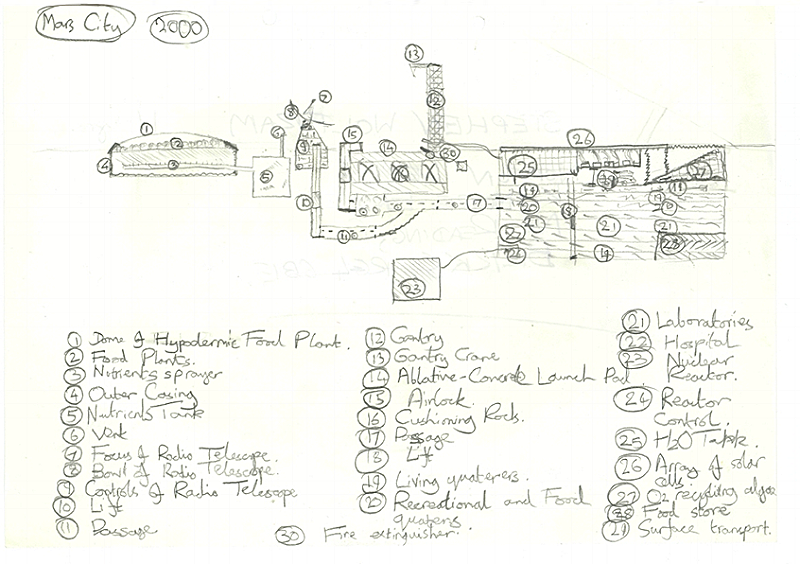

At that time it was assumed that there would be colonies on Mars, and I began to make small projects for spacecraft.

I became interested in engines and ion batteries, and when I turned 11 years old, physics became my main interest.

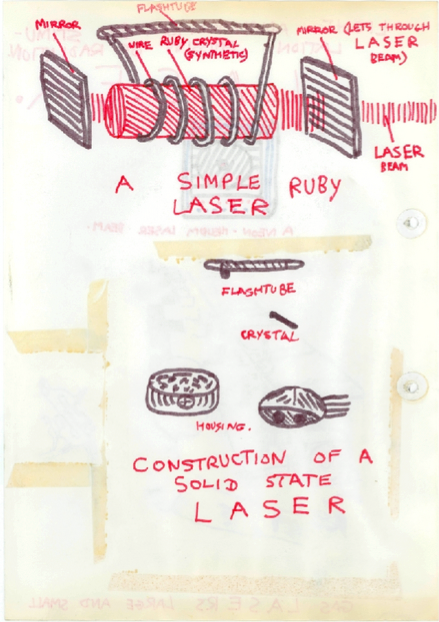

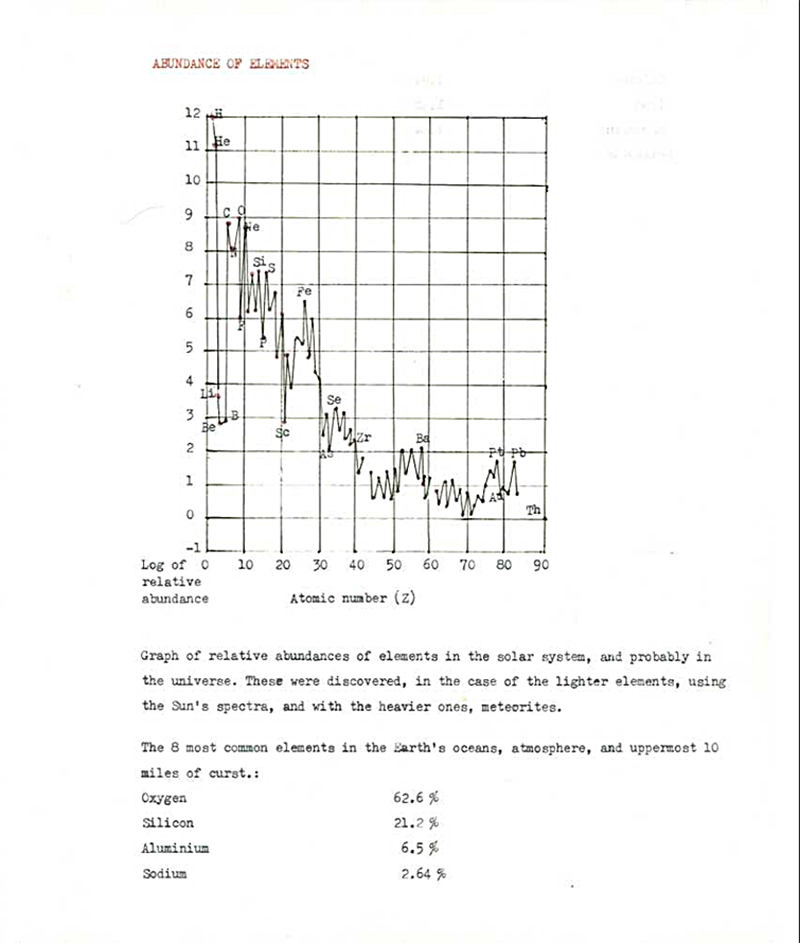

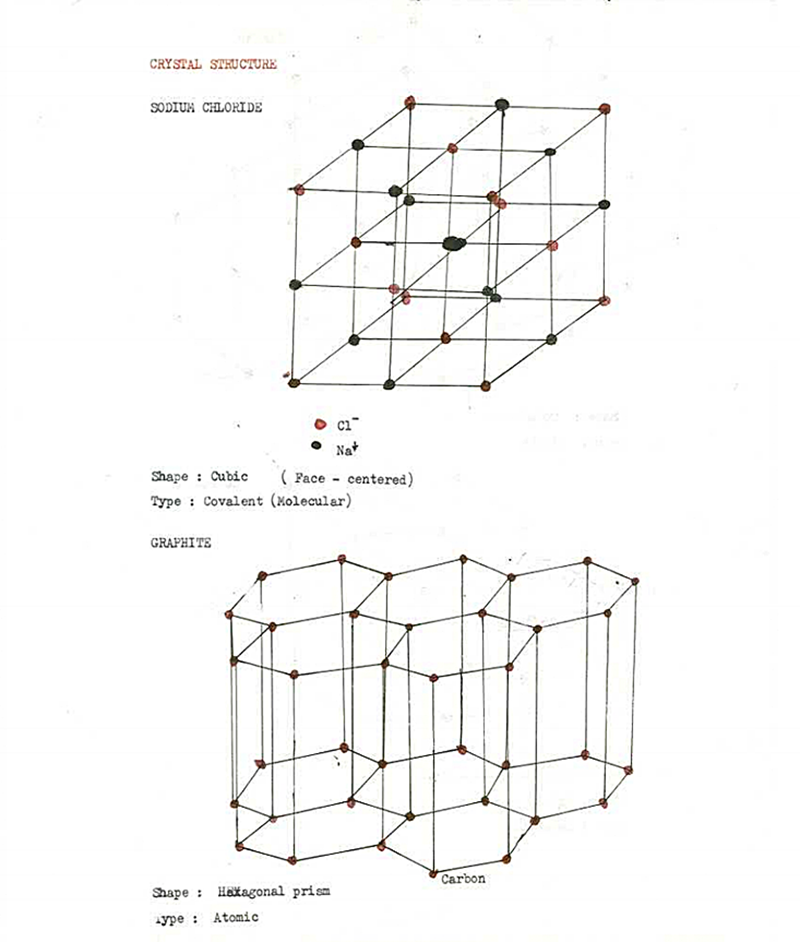

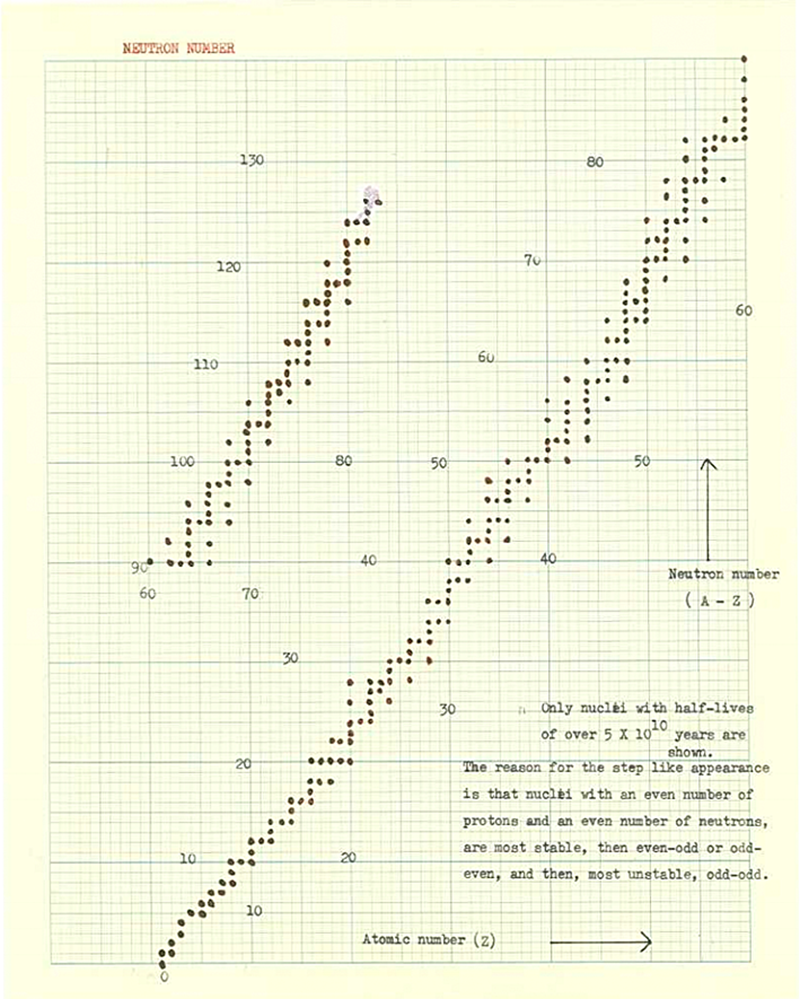

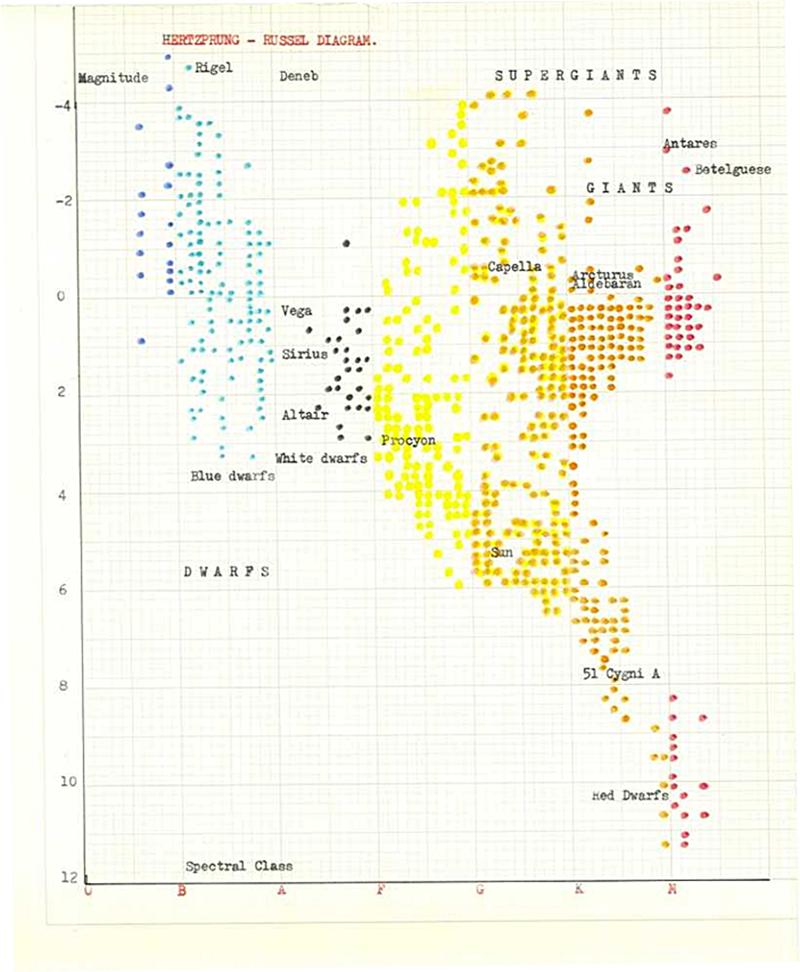

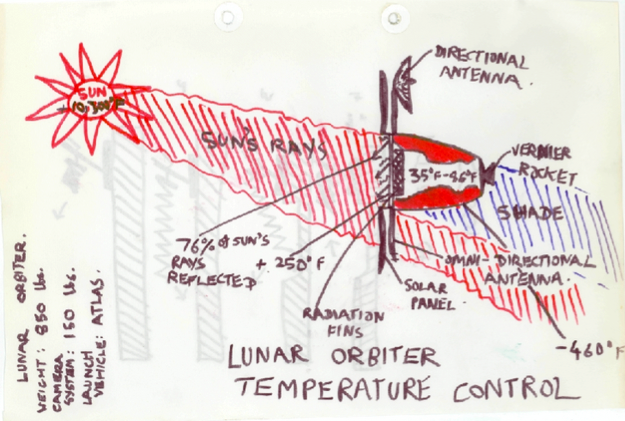

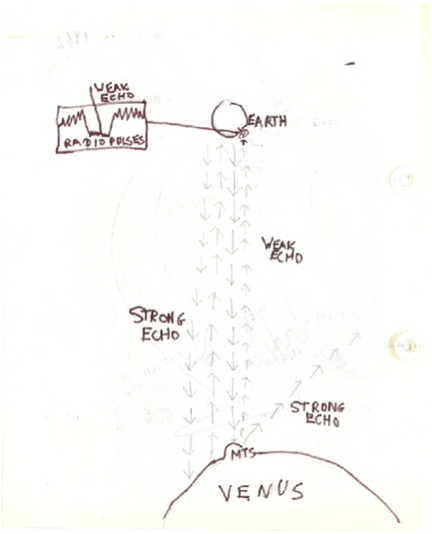

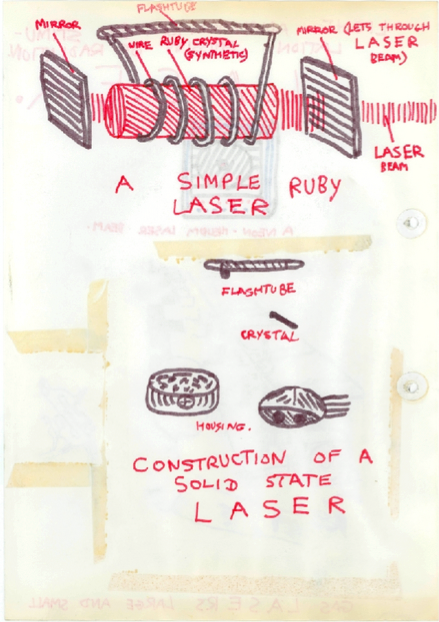

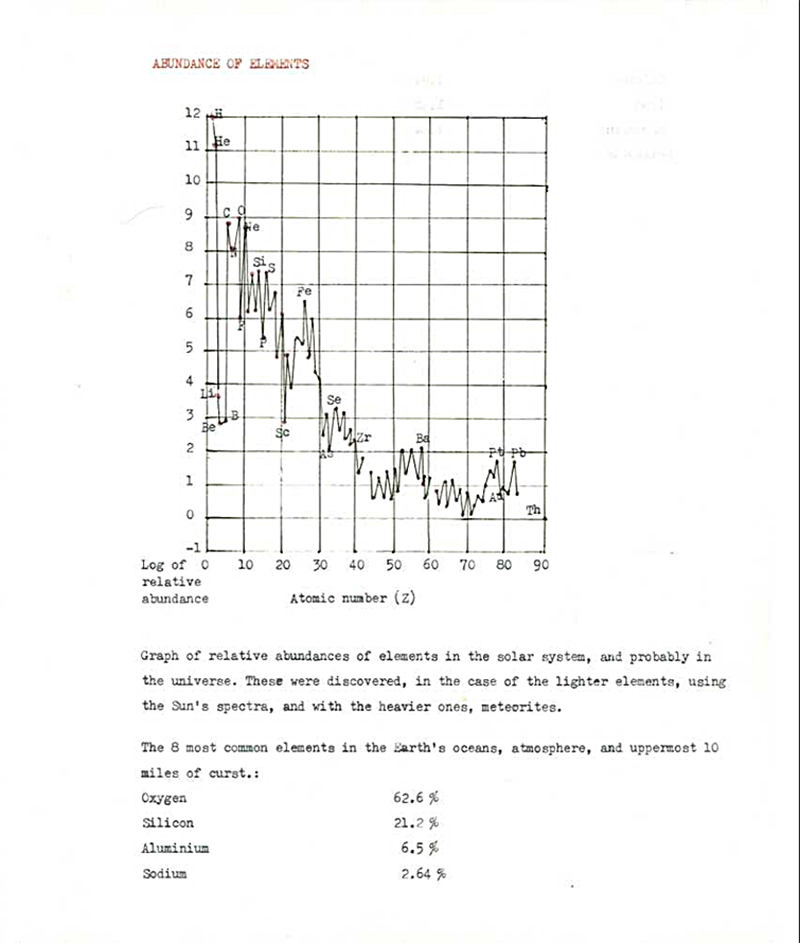

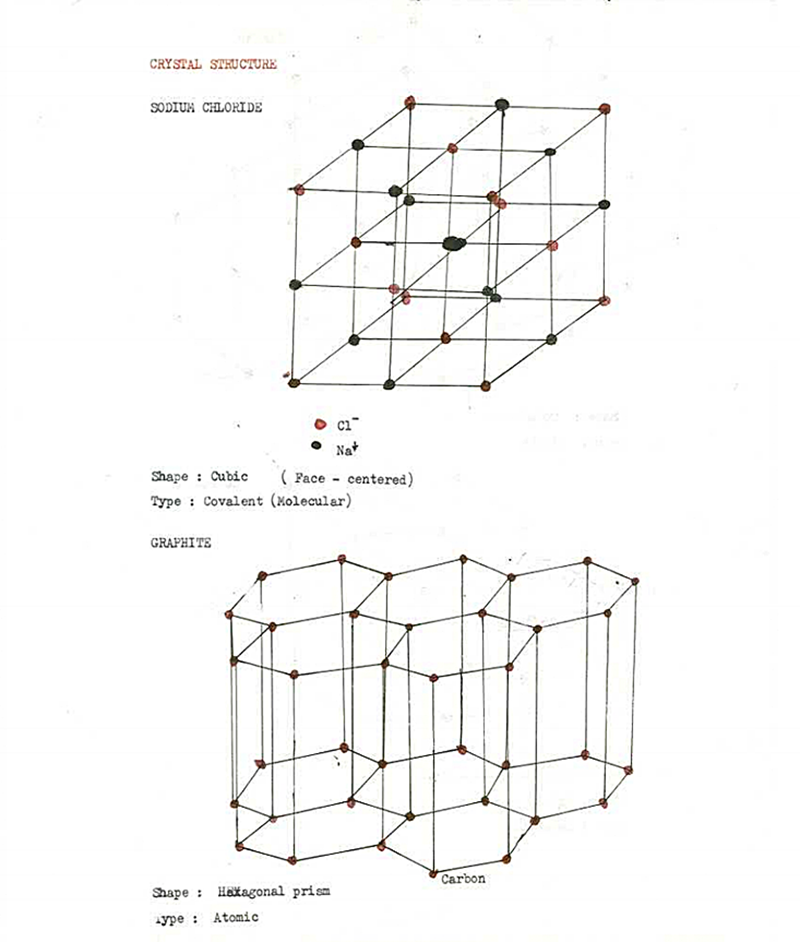

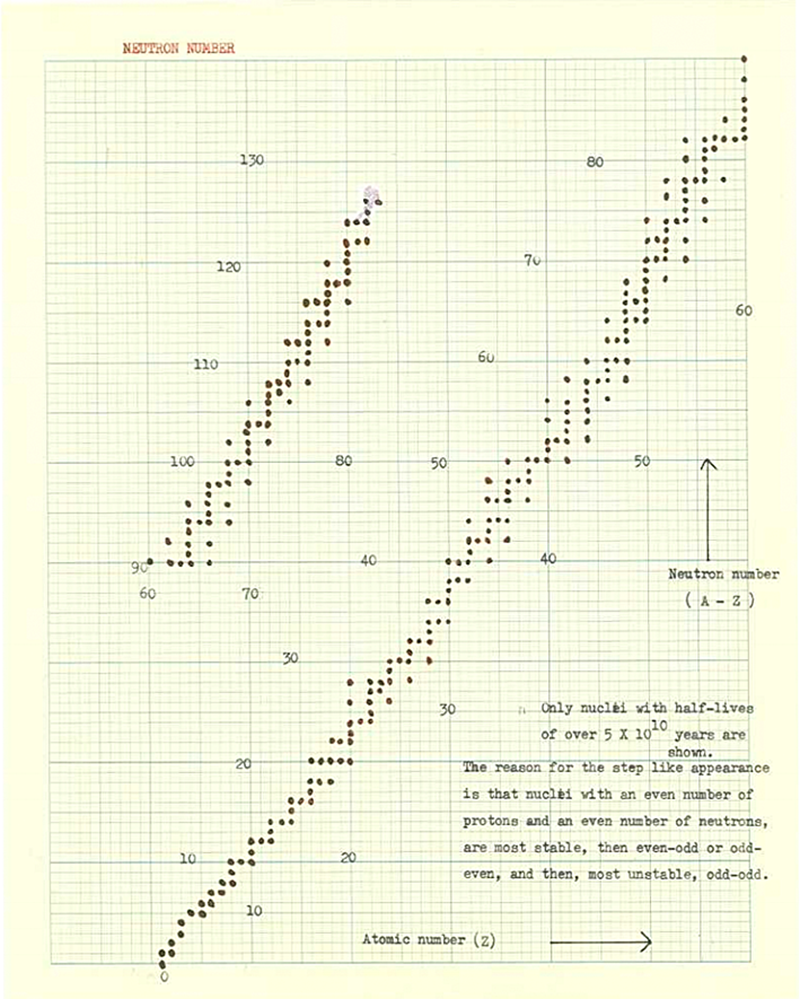

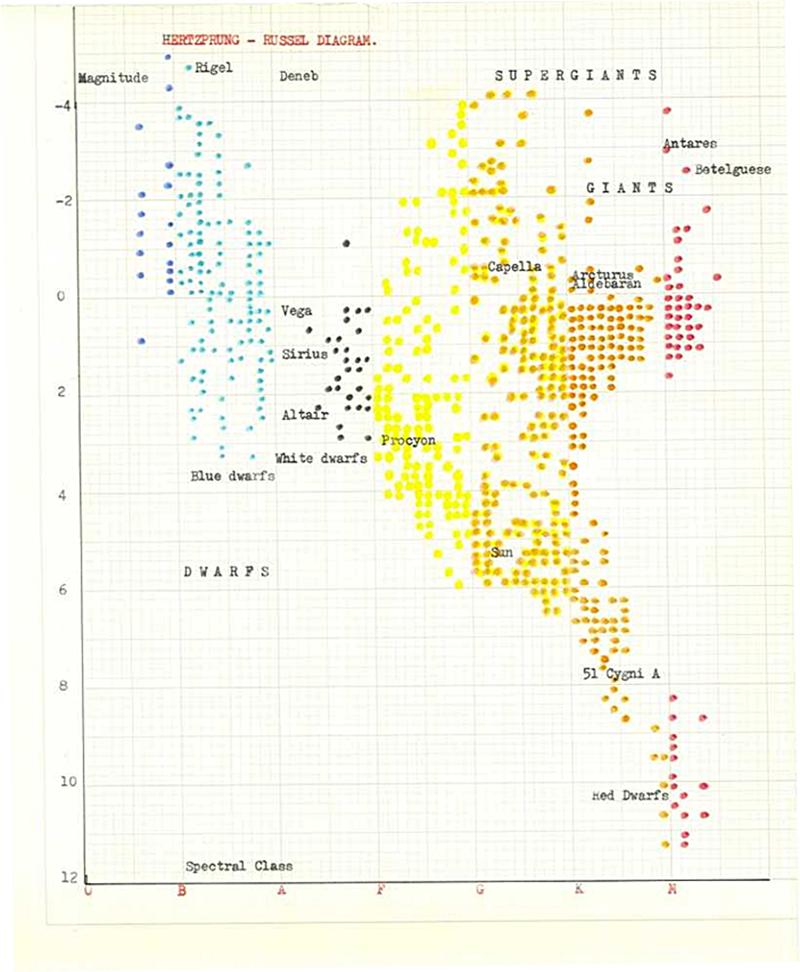

And I found that you can learn a lot and quickly if you just read books (it had nothing to do with school). I chose various areas of physical science and tried to organize knowledge about them into a system. In the end (when I was already 12) I spent the summer, bringing together all the facts about physics. I suppose you could call some of this “visualization.” And, really, now it is, like so much more, easy to find on the Internet :

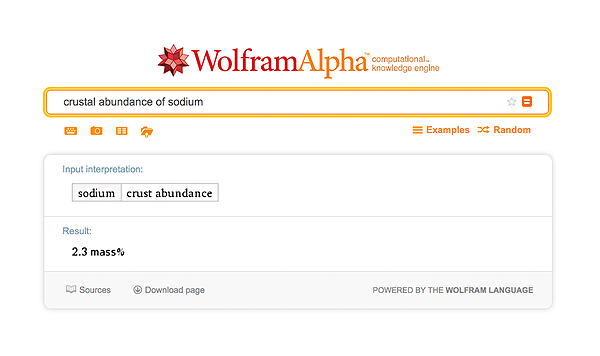

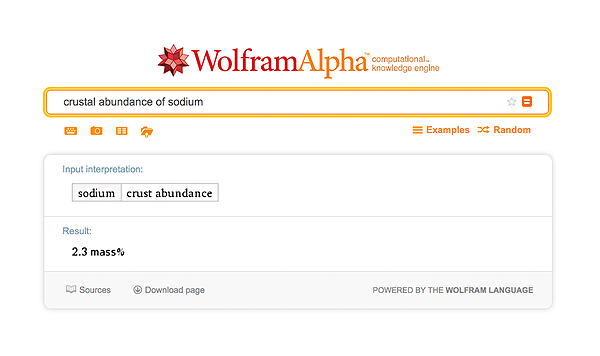

A few years ago, I found this again (at the time of the Wolfram | Alpha) and thought, “ Oh my gosh, I've done the same thing all my life! ” And then I started to dial numbers from those times when I was 11 or 12 years to see if Wolfram | Alpha does the same thing: Of course , everything worked:

When I was 12 years old, following the British tradition, I went to the so-called public school, although in fact it was private. I went to Eaton - the most famous of these schools, which was founded 50 years before Columbus arrived in America. I even received the highest scholarship among my children in 1972.

Yes, all the time they wore coats, and royal scholars like me also wore robes that protected from rain, etc. I thought I had successfully avoided these annual pictures in the style of Harry Potter, but once I was captured on group snapshot:

And at that time with his Latin, Greek and mantles I led a kind of double life, because my real passion was physics.

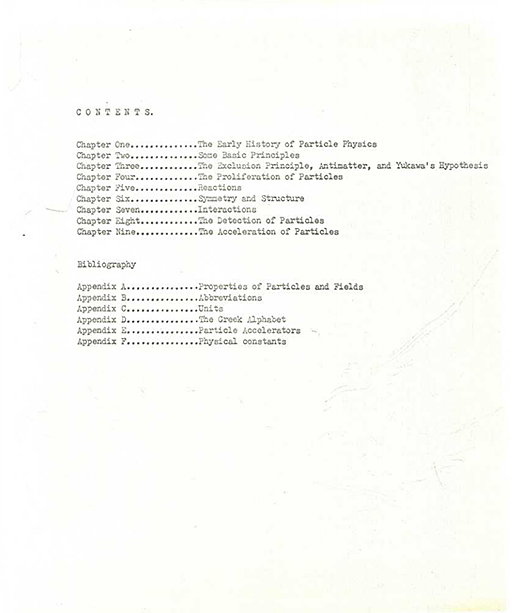

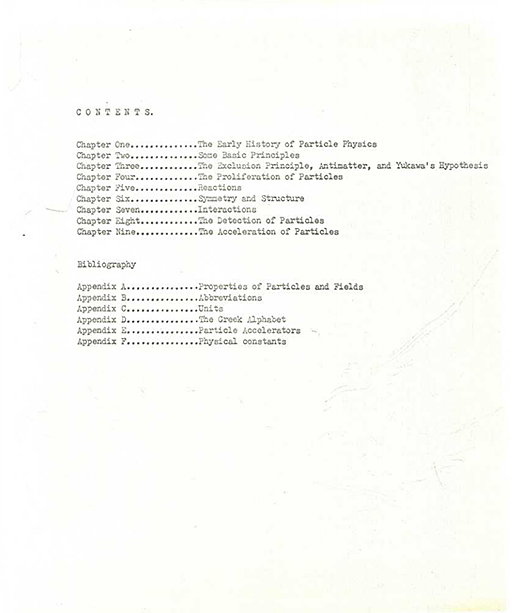

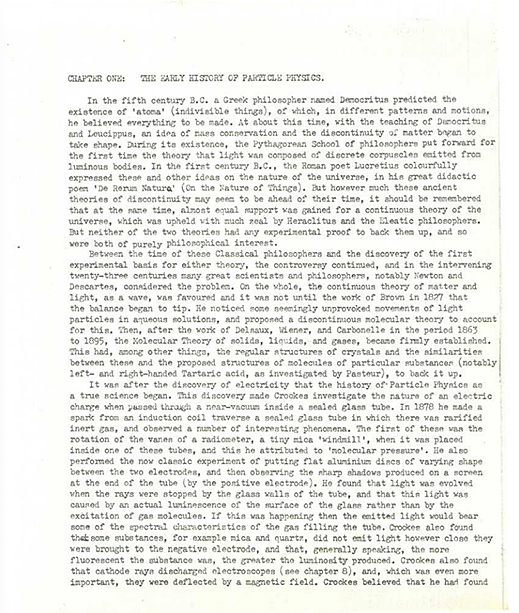

In the summer, when I turned 13, I gathered together brief information about particle physics :

And I made an important discovery: even a child can discover interesting things . And then I began to try to independently answer questions on physics or looked for answers in books, and by the time I turned 15, I began to publish articles on physics . No one asks how old you are when you send an article to a journal about physics.

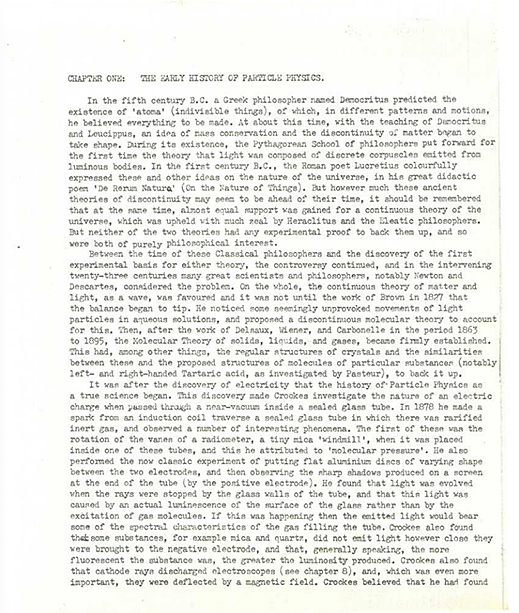

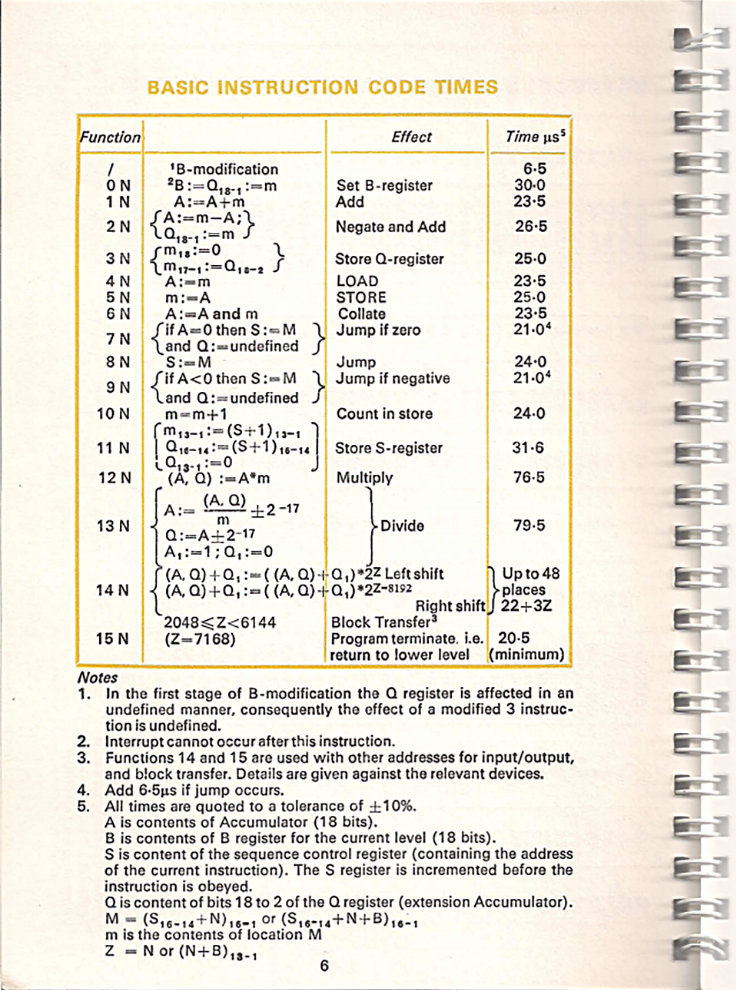

When I was 12, something important happened: I met my first computer. This is Elliot 903C . This is not exactly the one I used, but similar:

He appeared at Eton along with my teacher Norman Routledge, who was a friend of Alan Turing . He had an 18-bit ferrite core on 8 kiloswords, programmed by means of a mylar tape, often on SIR (assembler).

Often it seemed that one of the most important skills was rewinding the tape after passing through an optical reader.

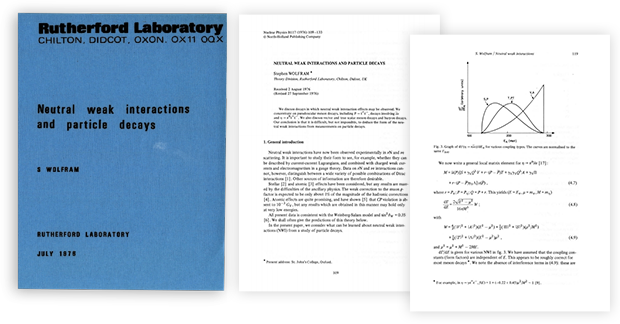

Anyway, I wanted to use a computer to do physics. When I was 12, I received this book :

I assumed that the image on the cover is simulated gas molecules, demonstrating increasing randomness and entropy. As is often the case, several years later I discovered that this picture was actually a kind of fake. But when I was 12, I really wanted to play it with a computer.

It was not so easy. The positions of the molecule should have been real numbers; it was necessary to have a collision algorithm, and so on. And, in order to adapt to the Elliott 903, I eventually simplified a lot - and came to what turned out to be a 2D cellular automaton.

Well, ten years after that, I made some big discoveries in the field of cellular automata . But then I was unlucky with my rule of the cellular automaton, and ended up doing it without finding anything. And in the end, my biggest achievement was writing bootable punched tapes for Elliott 903.

There is one serious problem with the mylar tape: it can get charged with static electricity and zazhevyvat holes, so the bits will be read incorrectly. Well, for my bootloader, I came up with error correction codes, and set them up so that if the check failed, the tape in the reader stopped, and you could pull it back a couple of meters to reread.

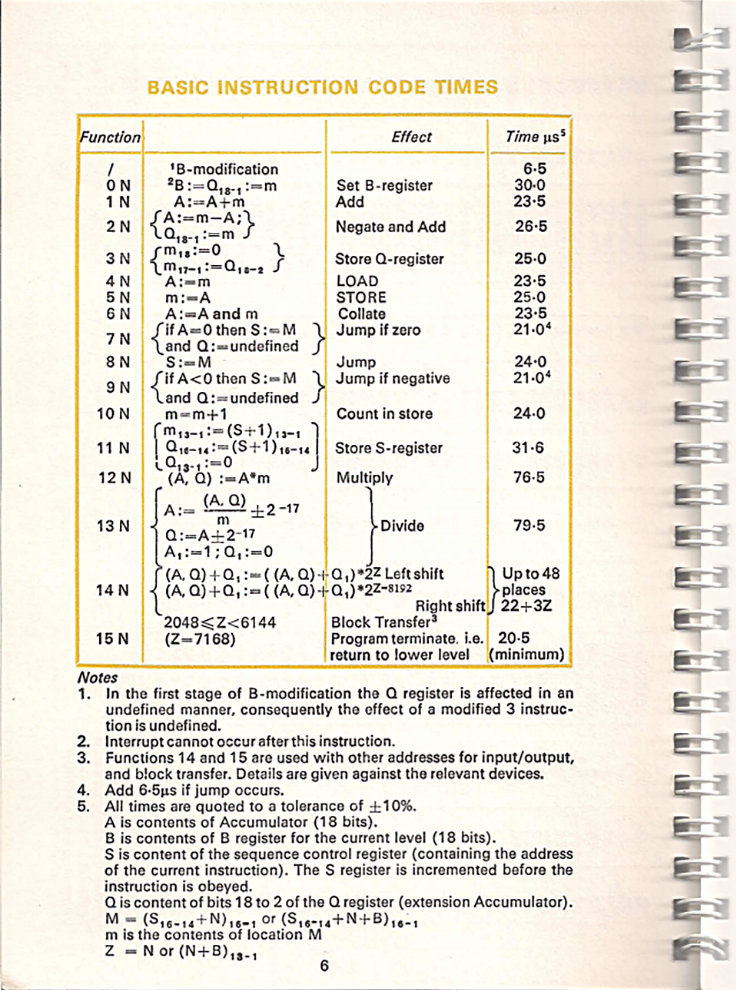

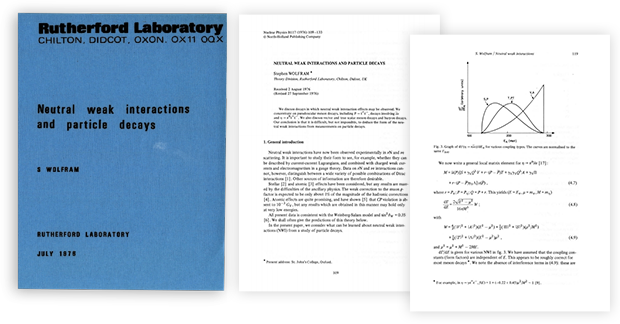

OK, so by the time I was 16, I published articles on physics and even became recognizable, left school and went to work at a British government laboratory called Rutherford Laboratory , which was involved in elementary particle research.

Now you may recall the school report card, from which it was clear that I was not very good at math. Things got a little better when I started using a slide rule, and then, in 1972, and a calculator. But I never liked doing math at school, or doing math in general. And there is a lot of mathematics in particle physics, so this dislike of mine was a problem.

Two things helped me in Rutherford's laboratory. First, a desktop computer with a plotter, on which I could do very beautiful interactive calculations. And, secondly, the mainframe for things that I programmed in Fortran.

After Rutherford's lab, I went to college at Oxford . For a very short time, I realized that this was a mistake, but at that time there was no need to attend lectures, so I just hid and did my research in physics. And basically I spent my time in a well-conditioned underground in the building of nuclear physics with terminals connected to a computer and ARPANET .

And just then - in 1976 - I first started using computers for practicing symbolic mathematics, algebra, and others. Feynman diagrams in elementary particle physics include a lot of algebra. And in 1962, it seems, the year three physicists met at CERN and decided to try using computers to work in this direction. They had three different approaches. One wrote a system called ASHMEDAI on Fortran . Another - under the influence of John McCarthy from Stanford - a system called Reduce in Lisp . And another wrote a system called SCHOONSCHIP on a CDC 6000 in assembly language with mnemonics in Dutch. Curiously, a few years later, one of these physicists won the Nobel Prize . It was Tini Veltman - the one who wrote SCHOONSCHIP in assembler .

In any case, in 1976, few people except the creators used these systems. I started using them all. However, my favorite was a completely different system, written in Lisp at MIT in the mid-1960s. It was a system called Macsyma . She worked on the Project MAC PDP-10 computer. And what was important to me as a 17-year-old child from England was that I could get to her on ARPANET.

There was a host 236. So I entered something like @O 236 and connected to an interactive operating system. Someone took the login SW. So I became Swolf and started using Macsyma.

I spent the summer of 1977 at the Argonne National Laboratory , where some of the ideas of physicists were tested in the room with the mainframe.

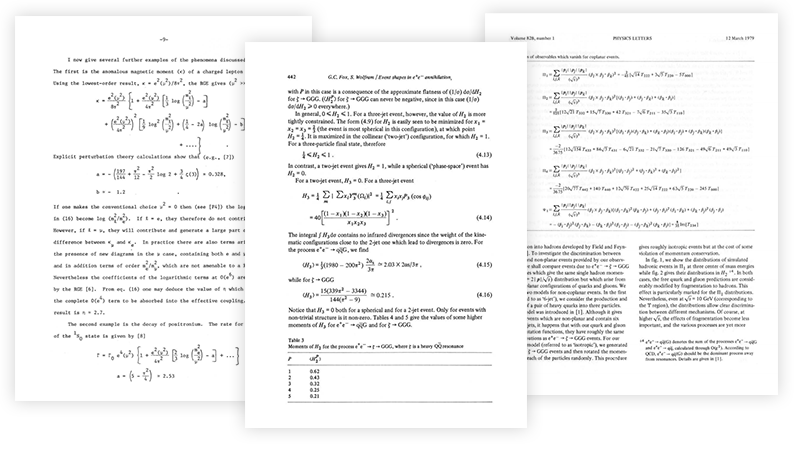

Then, in 1978, I went to a graduate student at the California Institute of Technology . I think that by this time I was the largest user of computer algebra in the world. And it was so great that I could figure out all these things so easily. I got great pleasure using ornate and complex formulas in my works.

I gained a reputation as a great calculator. Of course, she was 100% undeserved, because I did not think, but the computer. Although in reality (to be fair), something remained with me: doing calculations for so long, I earned a new kind of intuition. I did not take the integrals very well myself; but I could go back and get ahead with the computer, intuitively understanding what it was worth trying, and then running experiments to see what worked.

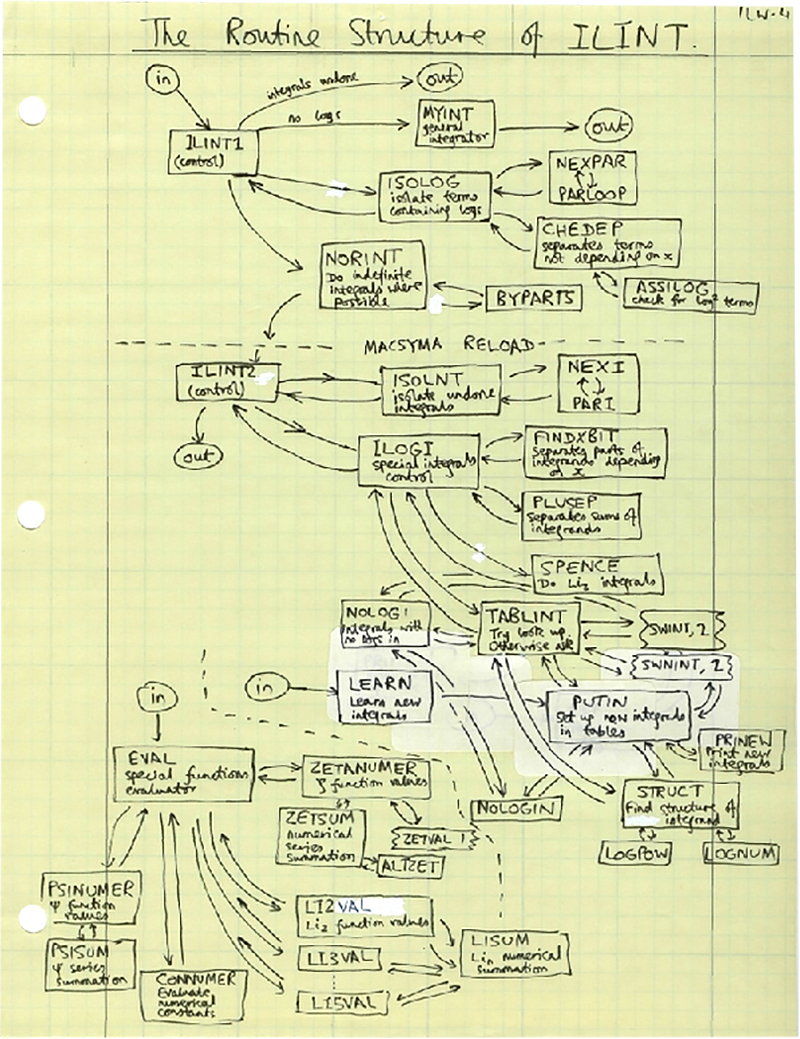

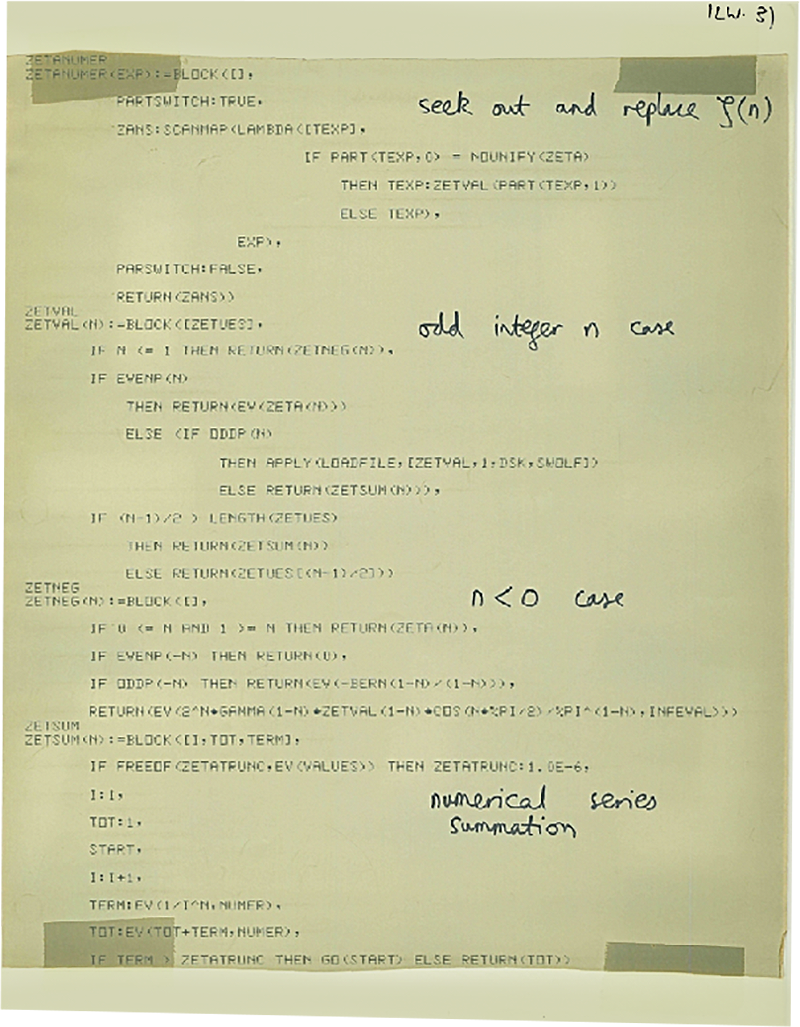

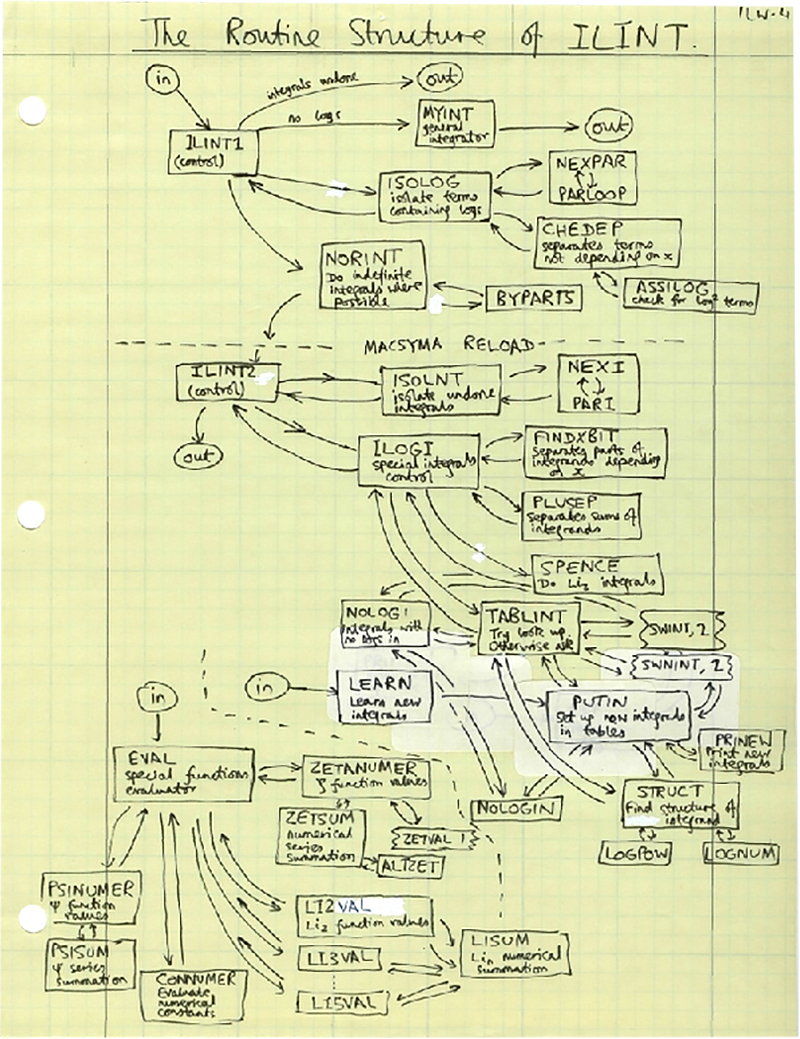

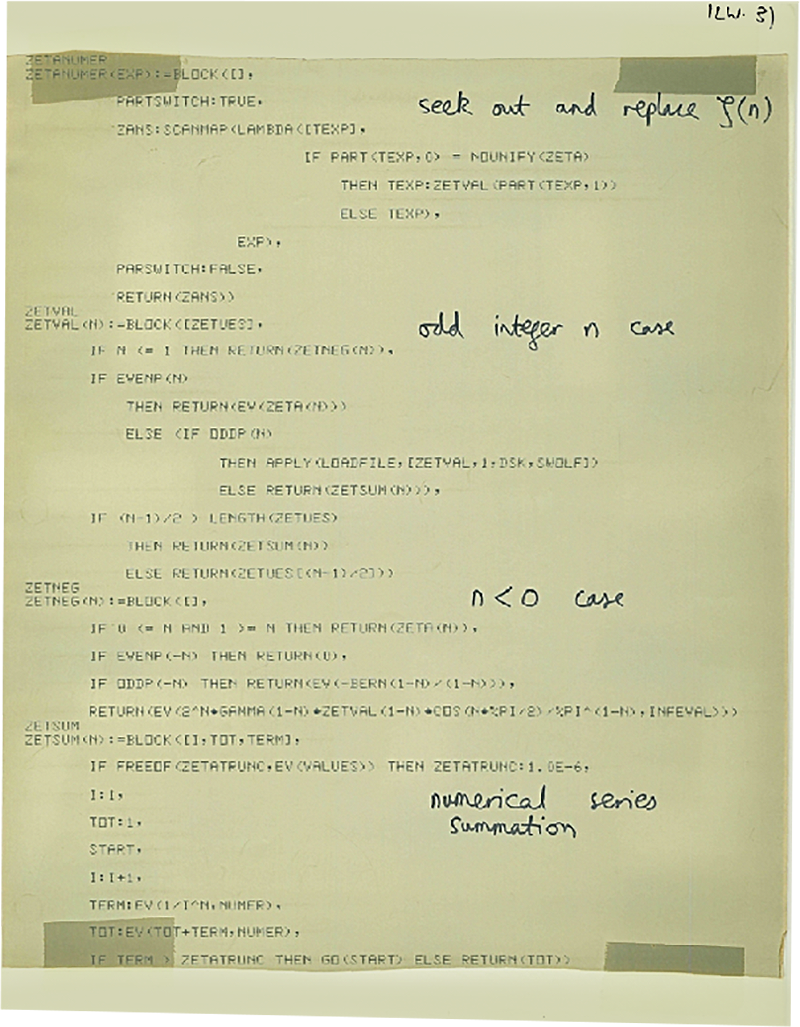

I wrote large chunks of code for Macsyma. And somewhere in 1979, I ran into a wall - something new was needed. Notice the ominous MACSYMA RELOAD line in the diagram.

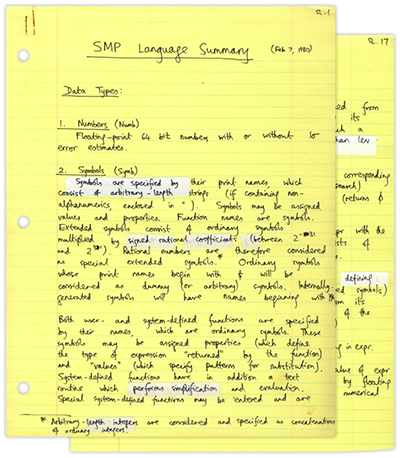

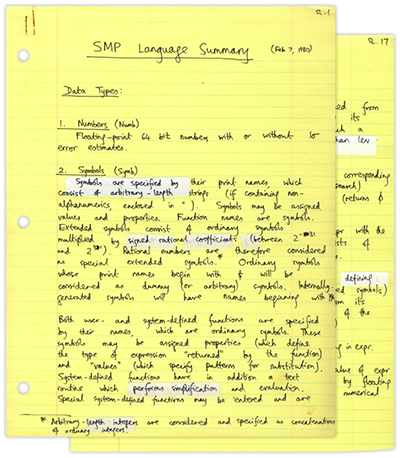

Later, in November 1979 and shortly after my twentieth birthday, I collected some papers, called them a dissertation and received my doctoral degree . And a couple of days later I visited CERN in Geneva and began to think about my future in physics (as it seemed to me then). The only thing I was sure about at the time was that for my calculations I would need something besides Macsyma. That's when I decided to build a system to fit my needs. And I started to create a specification .

At first it was supposed to be ALGY - Algebraic Manipulator. However, I quickly realized that I must do much more than just algebraic manipulations. I knew most of the general-purpose computer languages like Algol , Lisp, and APL . But for some reason they did not capture the area in which I wanted to create my system.

I think I did what I learned from physics: I went deeper in order to find atoms and understand what was happening. I knew something about mathematical logic and the history of attempts to formulate something using logic, even when my mother’s textbook on philosophical logic did not exist.

The history of these attempts at formalization is very interesting and is associated with many well-known names: this is Aristotle and Leibniz (see the post on Habré " A detailed look at the legacy of Leibniz "), and Frege , and Peano , and Hilbert , and Whitehead , and Russell , and etc. But this is another conversation. However, in 1979, thoughts led me to the idea that I invented a structure based on the idea of symbolic expressions and their transformations.

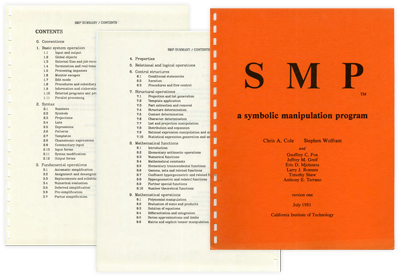

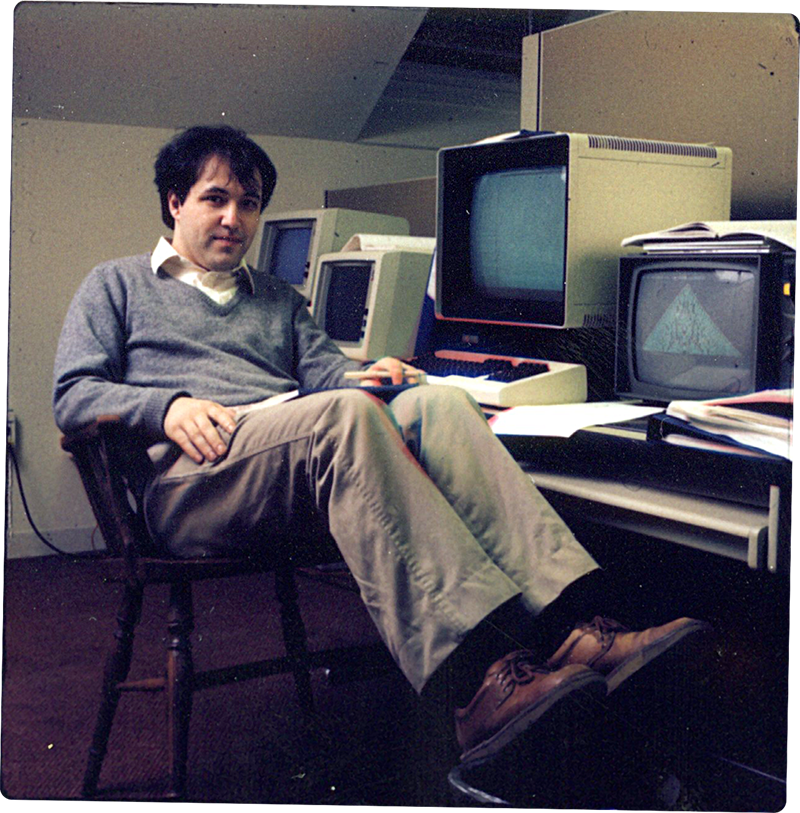

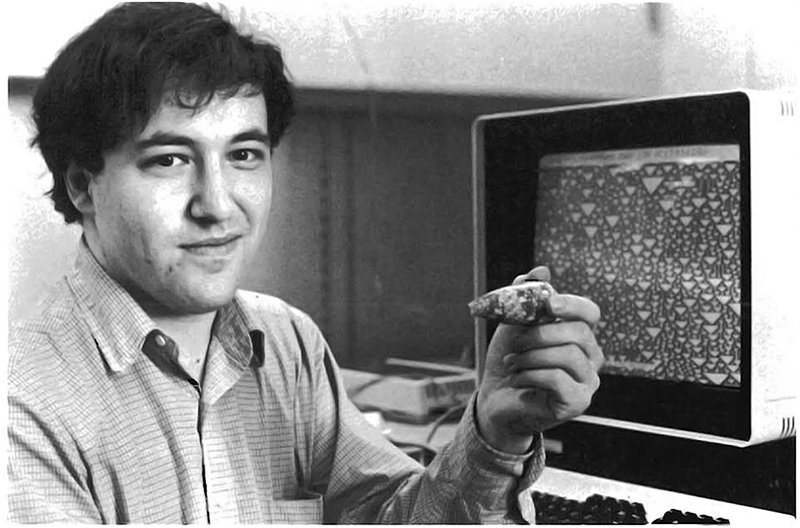

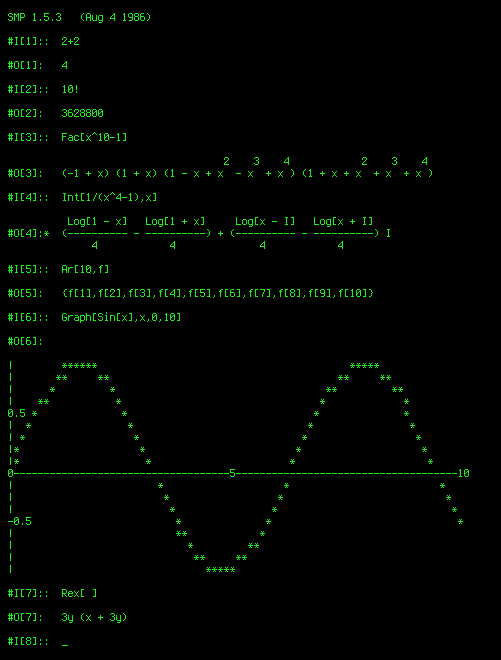

What I got is what I called the SMP: Symbolic Manipulations Program , and I began to attract people from all over the California Institute of Technology to work on it. Richard Feynman was at meetings where I discussed the structure of my program and offered various ideas for interacting with the system. Meanwhile, the Faculty of Physics received a VAX 11/780, and after some wrangling, Unix was launched on it. At the same time, a young physics student named Rob Pike - the creator of the Go programming language - convinced me that I had to write code for my system in “the language of the future”: C.

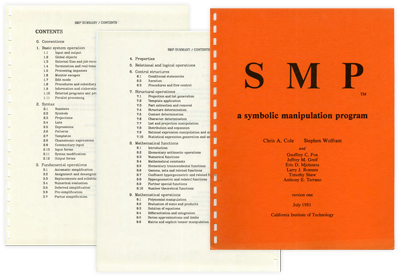

I succeeded in writing C code, and for a while I wrote an average of about a thousand lines a day. And by June 1981, with the participation of several prominent personalities, the first version of SMP was ready - along with a large book of documentation that I wrote.

Good; You may ask: can we see SMP? When we worked on SMP, I had a brilliant idea that we should protect the source code with encryption. And, as you may have guessed, after three decades, no one could remember the password. Until some time ago there was one situation.

Implementing my other idea, I used a modified version of the Unix program for encryption to make more secure encryption. In honor of the 25th anniversary of the Mathematica system a couple of years ago, we implemented a crowdsourcing project on encryption cracking. Unfortunately, compiling the code was not an easy task - although with the help of a 15-year-old volunteer, we finally got something working.

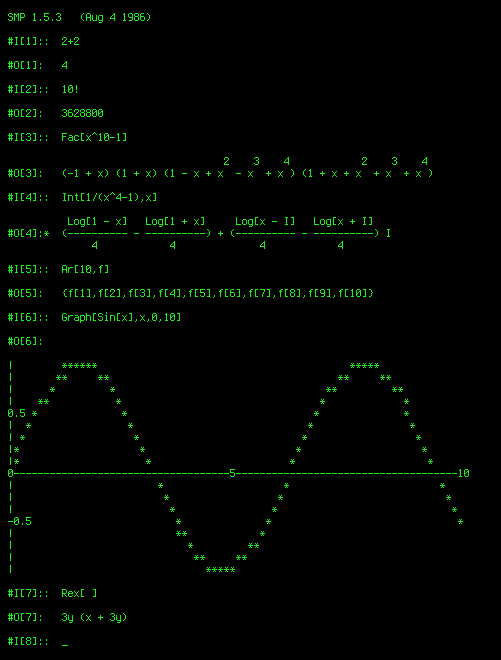

And here it is: it works inside the VAX virtual machine emulator, so I can show (for the first time in 30 years) a running version of SMP.

SMP was a mixture of good and not-so-good ideas. For example, Tini Veltman, the author of SCHOONSHIP, suggested to me a bad idea: he proposed to represent rational numbers as a floating point, so that one could use faster floating-point instructions on several processors. However, there were many other bad ideas.

There were also interesting ideas - like those that I called “projections”: in fact, the union of functions and lists. With the exception of some troubles, they were wonderful. And something strange happened with almost all vectors with consecutive integer indices.

But overall, SMP worked very well, and I, of course, decided that it was a very useful thing. So now the next problem was to decide what to do with it. I realized that for such work a real team is needed, and the best way to get it is to transfer the business to commercial terms. However, at that time I was 21 years old, and I knew nothing about business.

Then I came to the university office of technology commercialization and asked them what to do. But it turned out that they did not know, because " mostly professors do not come to us; they open their own companies ." " Well, " I said, " can I do this? " And right there, the lawyer pulled out some kind of manual, looked into it and said: " it says that the copyright of the materials belong to their creators, and the software, too, so yes: you can do whatever you want ."

So I went out in order to try to create my own company. Although in the end it was not so easy, because the university suddenly decided that I should not have done what I wanted.

A couple of years ago, when I was at Caltech, I ran into a 95-year-old guy who was the rector at the time, and who finally filled out the rest of the details of what he called the " Wolfram case ." It was more strange than you can imagine. I will not talk about it. Suffice it to say that the story began with Arnold Backman , a post-doc from 1929 from California Technological, who claimed his rights to the pH meter and founded Beckman Instruments - and then, in 1980, being chairman of the board of trustees of the same institute, he was upset about for having discovered genetic sequencing technology at Caltech, and left to create Applied Biosystems .

The company I created has withstood a storm, even if I finally left the California Institute of Technology, which, in turn, did away with the strange software ownership policy, which has long influenced their efforts to find personnel in the computer industry.

Having founded Computer Mathematics Corporation , I did nothing grand. I invited a person (who was twice my age) to the position of CEO. And pretty quickly everything began to go away from what I thought made sense.

One of my favorite moments of madness was the idea to get into the equipment business and build a station to launch SMP. Well, at that time no station had enough memory, and the virtual memory was not supported in the Motorola 68000 processor. , 68000-x , , , . , . , , — SUN — .

, 1981 , , , — — . , , , , Inference Corporation ( NASDAQ). SMP , - 40 000$ . , , .

— , , , " ", .

— - , . , — (SUN) ( — ):

- — ; — , . Thinking Machines Corporation . , WarGames , : " , ? ". Connection Machine , .

, (" ") , Ixis. , , . , , , (, ) , .

. ( ), , . , " Microsoft ". Microsoft.

1985 , , , . -, - , . , - .

— , . — , , Beckman Foundation, . , 1986 , - 100 .

, . , . , .

. , , , , . : -, ; , -, .

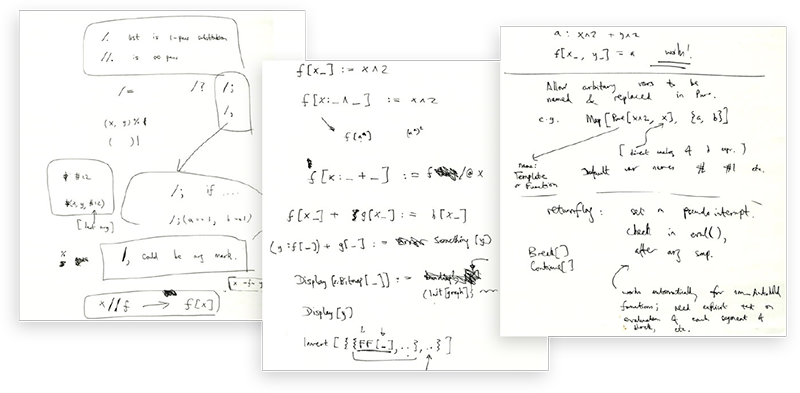

. SMP. C. PostScript , . , . , , , , .

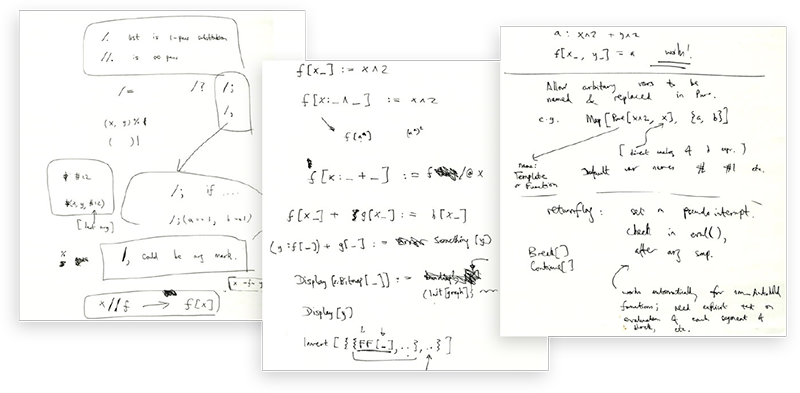

, , . SMP , , — , , Mathematica .

, , . , , ,— . Mathematica , SMP. SMP — Mathematica , .

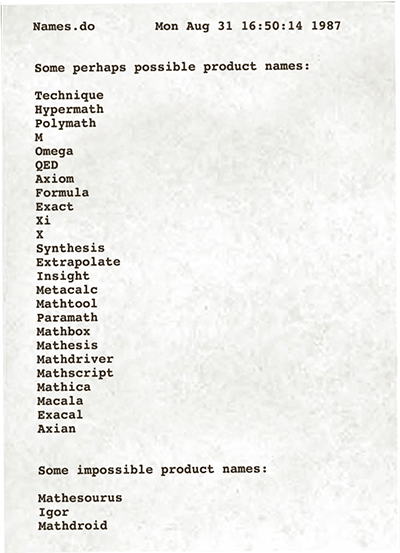

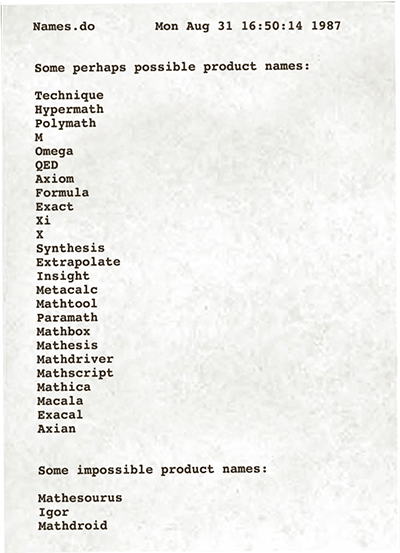

, Mathematica . Omega . . Polymath . Technique . — . , , ( - ) .

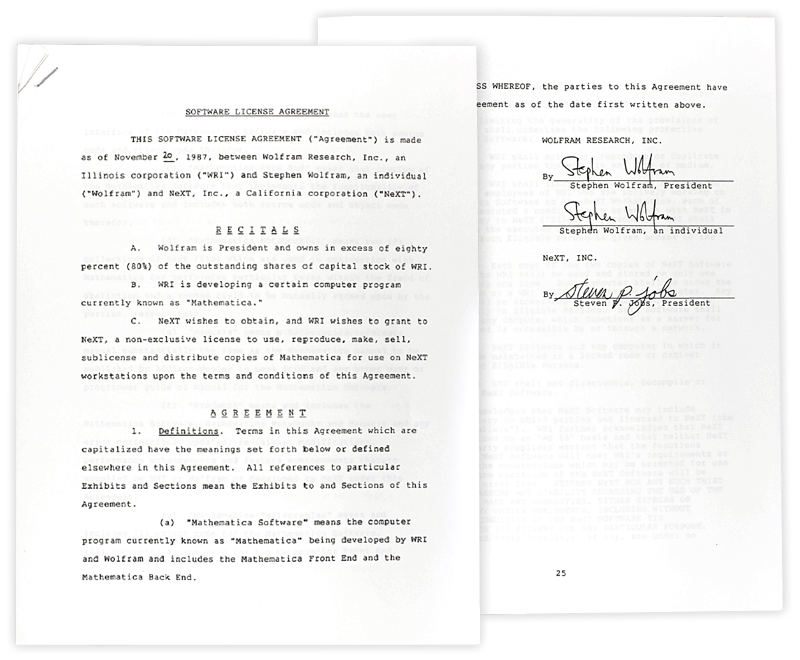

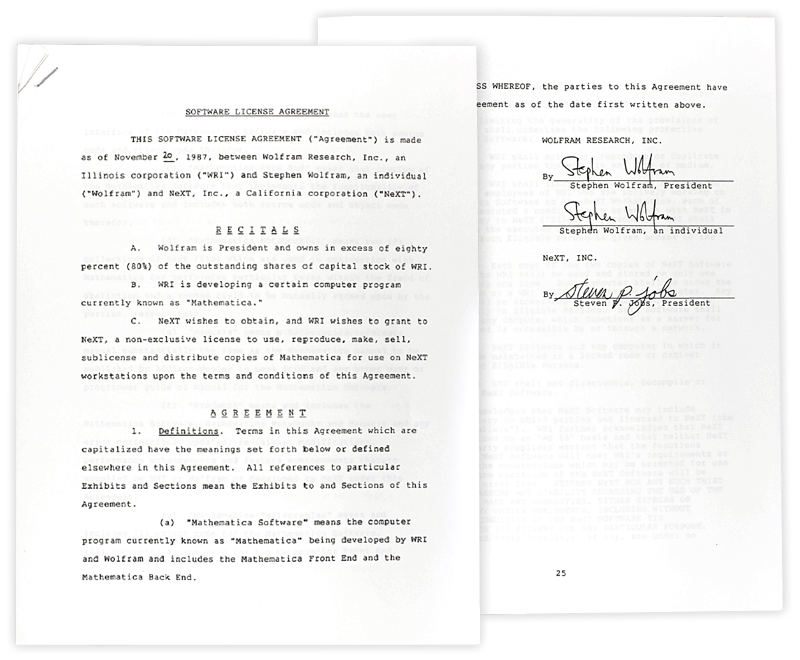

, . - , Adobe PostScript. , , , , , NeXT .

. , , " Mathematica ", , . , — . .

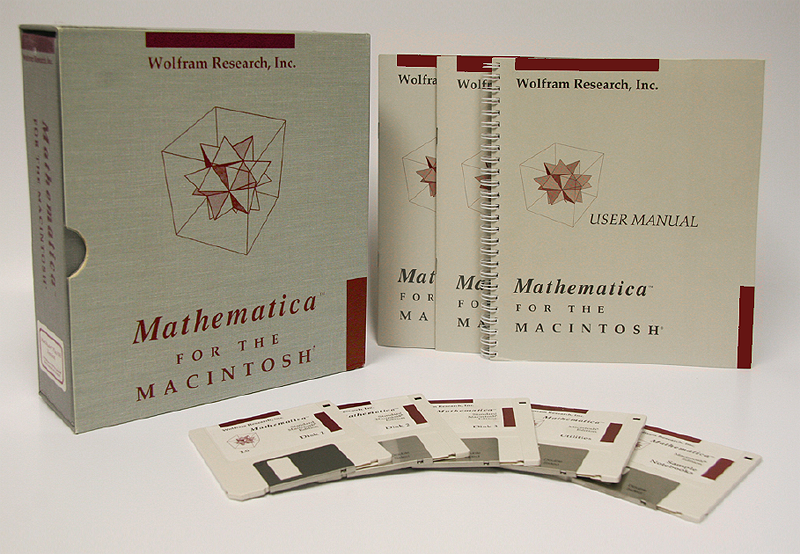

18 Mathematica. , . , , .

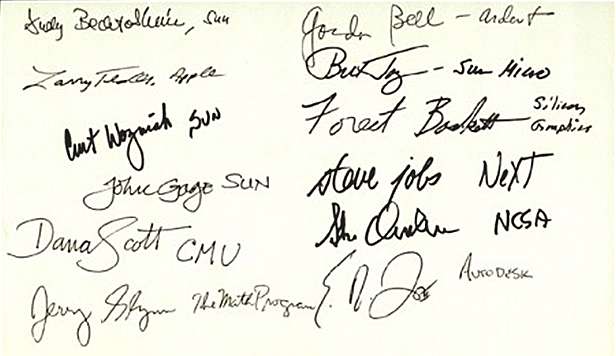

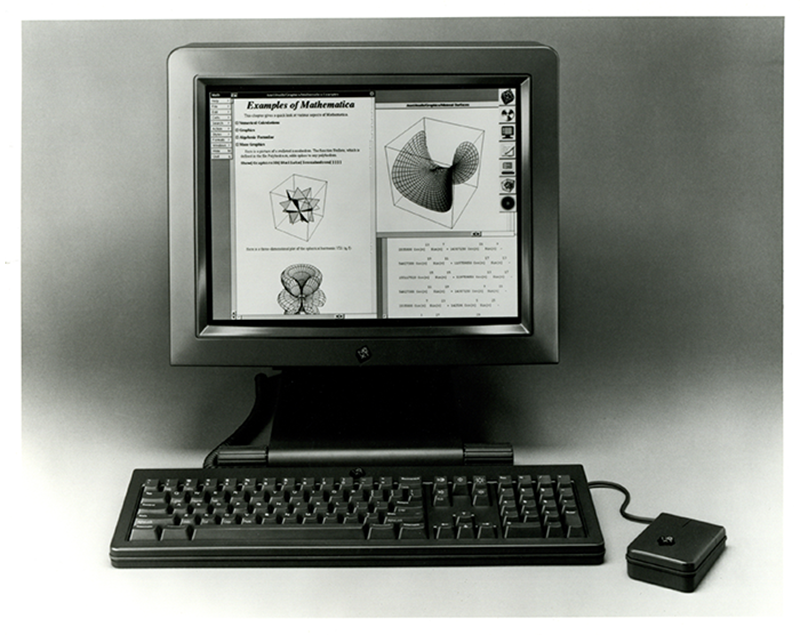

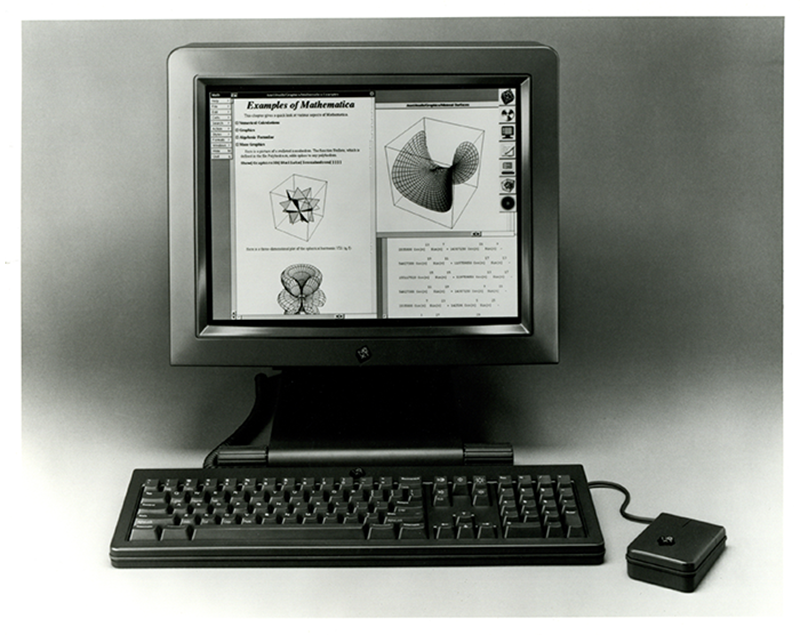

Mathematica NeXT :

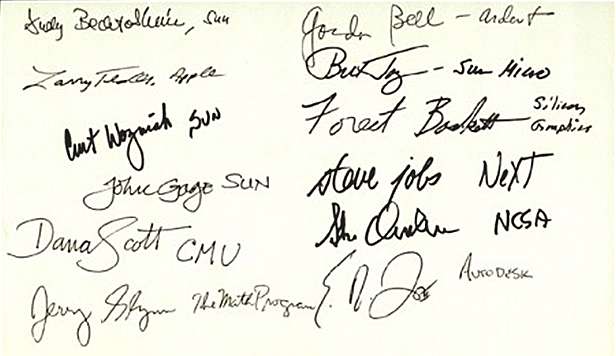

: Sun — ; Silicon Graphics . Ardent — . AIX/RT ( IBM ) — .

: 23 1988 .

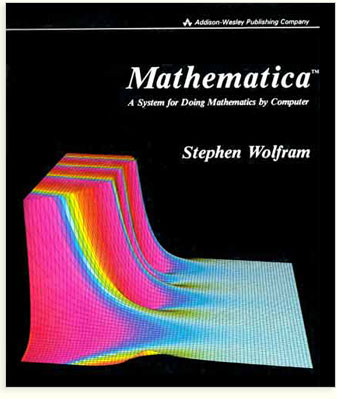

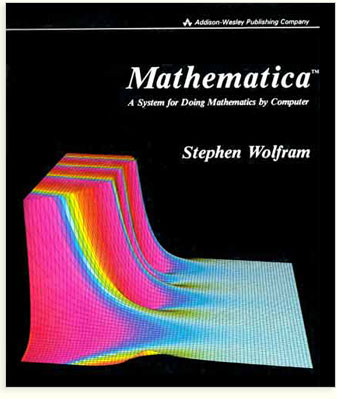

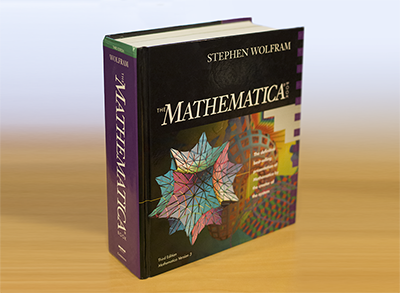

Mathematica: . Addison-Wesley , . , PostScript , . , , , Addison-Wesley.

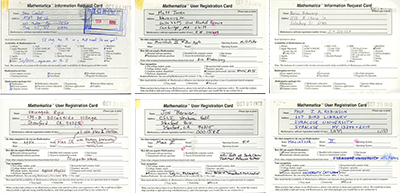

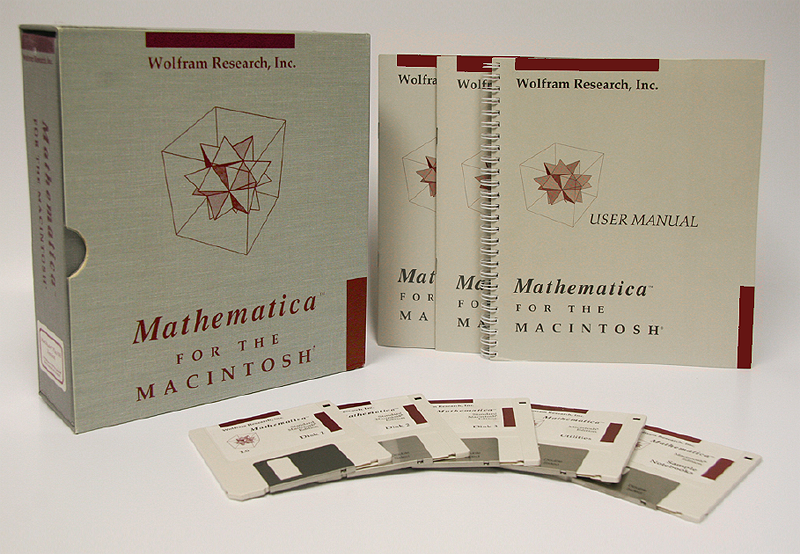

Mathematica — , , Techmart, -. Mathematica MS-DOS - (640). , Mac. ComputerWare — -.

. , . Apple . Sun , :

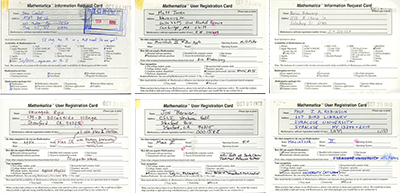

Mathematica. Mathematica — , Mathematica. , — , , - .

. . . , Time " Those Computers Are Dummies ", Mathematica .

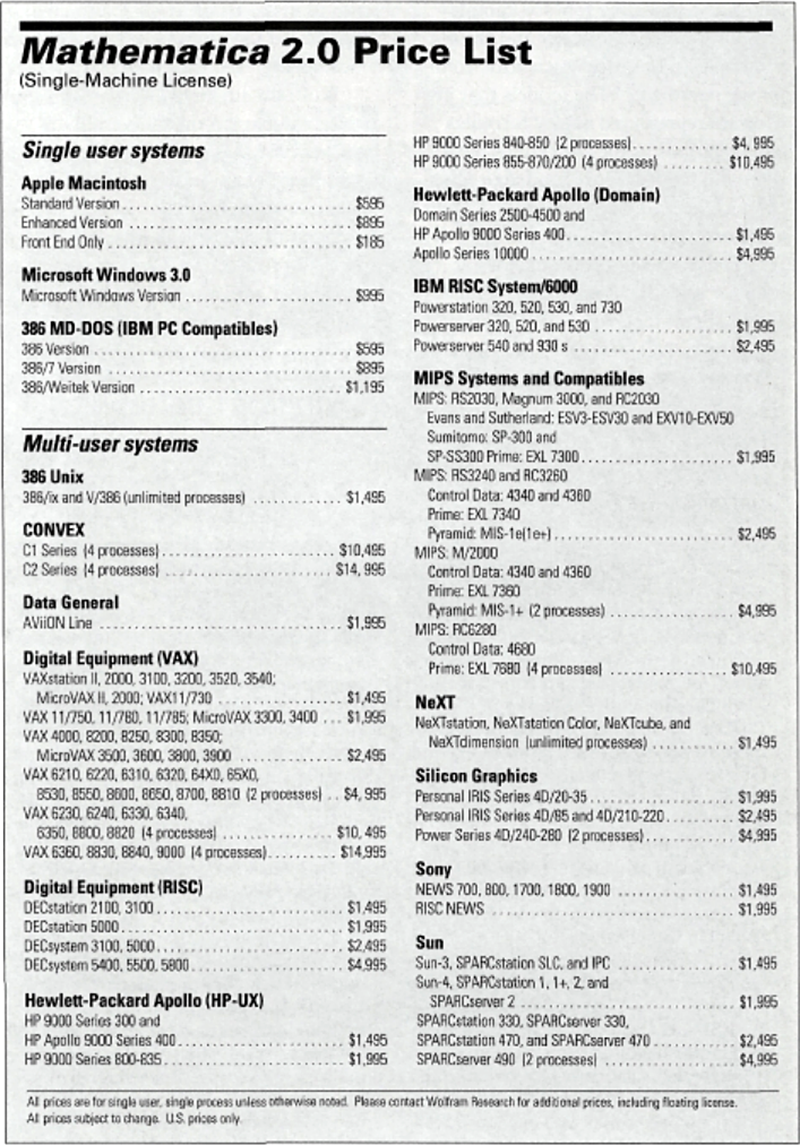

Mathematica . — , , Sony , .

. Cray-2 . Mathematica . - 2 + 2. — — «5». , .

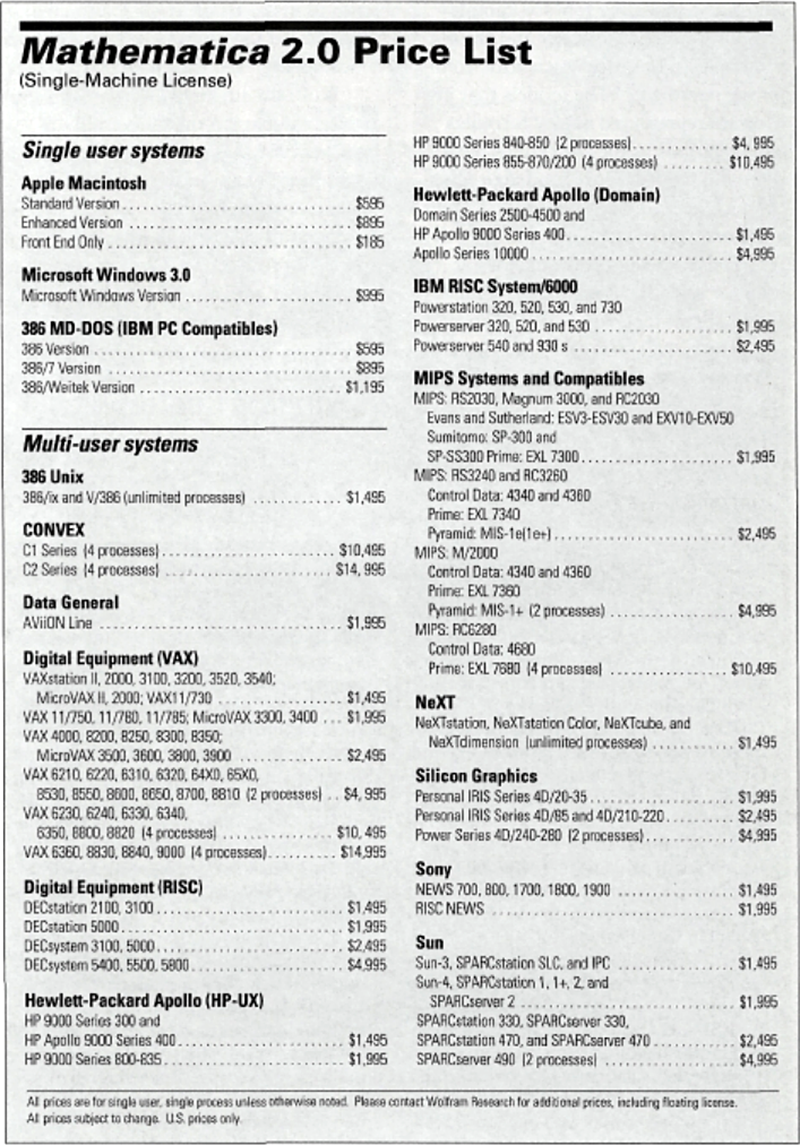

- 1990 — :

NeXT Mathematica . , , NeXT Mathematica. - , .

, - 150 . : , - , ? , ; , . , — — .

— , . , Mathematica . , . , — .

. , . 10 . , … , !

, , , — . . .

, 7 1994 :

, :

1996 Mathematica. 1988 . Mathematica . , . 1989^1989 — , 1989 , . Raspberry Pi , .

, 1988 ( , , , ) Mac NeXT, .

, - Mathematica. C (- C, , C ++ 1988 ). Mathematica, Wolfram Language — .

, , . — Mac, NeXT, Microsoft Windows X Windows. 1996 . 20 ; , .

Mathematica - , .

« », MathMobiles , .

Mathematica . , , . , 1997 Mathematica. , : , . , - — Mathematica. .

. DRM : " PC; Mathematica ! ". : " ". , , .

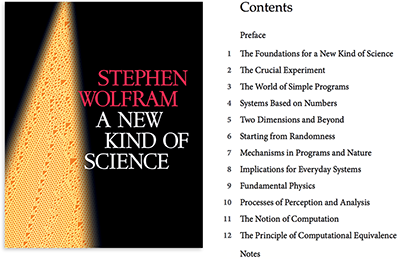

2002 , , , , :

" " , . , , , . , . , , , .

Mathematica, . , . 2006 , ( ). CDF ( ), Wolfram Demonstrations .

. . . , . , 36 , The Wolfram Functions Site 300,000+ :

, . , , , . -, . .

, , . . webMathematica , , …

Mathematica , , .

, , , , " ": -, . , - . 1980 , . .

, . " " " " . , , , " ", .

, , Mathematica. : " , , ? " , . : " - " . . , , .

. , , . — , . , . , .

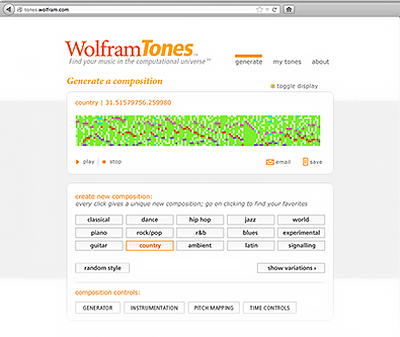

, , . , WolframTones. , . , . . Wolfram|Alpha — , .

, , Wolfram|Alpha . , , - , , .

, Wolfram|Alpha ( Mathematica Wolfram Language) . , .

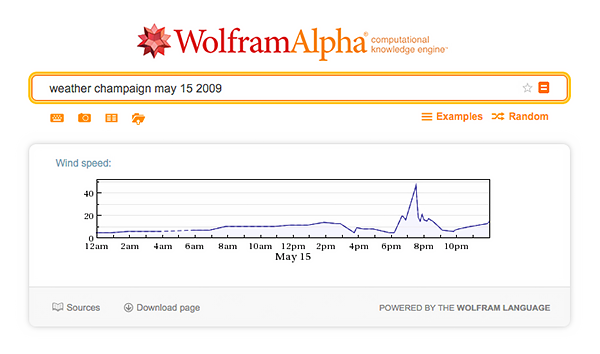

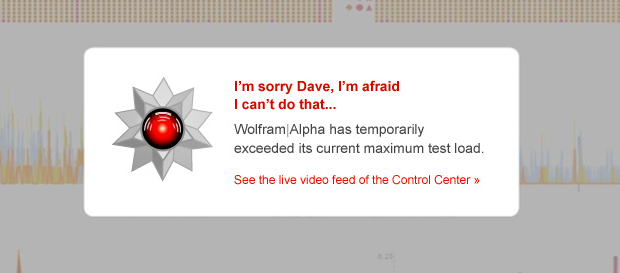

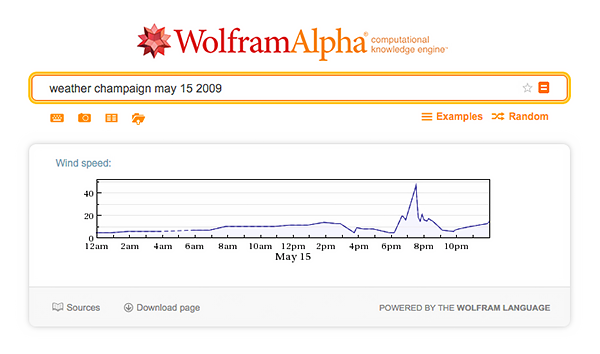

, 15 2009 . : , . Amazon -: , .

. , , . . , - , - , , , , , , , . , justin.tv ( YCombinator ), — .

« » , , . , : , .

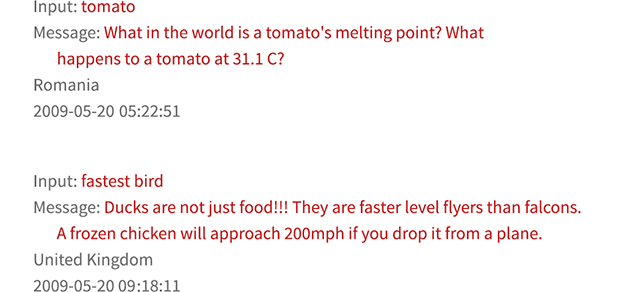

, . , . , — , .

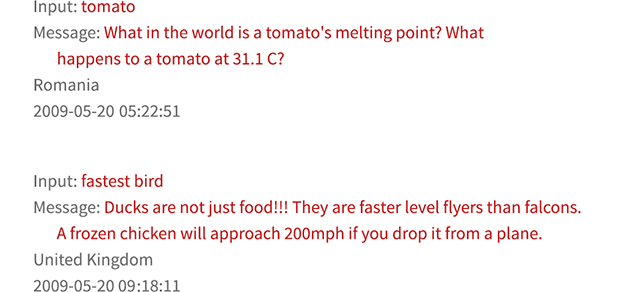

, , . . : ! Wolfram|Alpha ( ):

, , . , , 9:33:50 15 2009 , Wolfram|Alpha . . , .

. , - :

- : « , ?! ". — :

Wolfram|Alpha; . Microsoft Wolfram|Alpha Bing . Siri . Apple Siri, ( ) Wolfram|Alpha Siri.

, . Wolfram Language . , . 1990- Mathematica — M Language. , : , , 1993 . , .

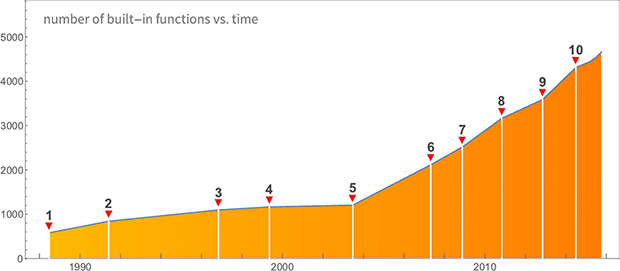

. , Wolfram|Alpha, , . , , , Mathematica . :

, 90% . " ", . , - . , Wolfram|Alpha , .

- — , , — .

Mathematica , . Wolfram Language ( ) — , — . …

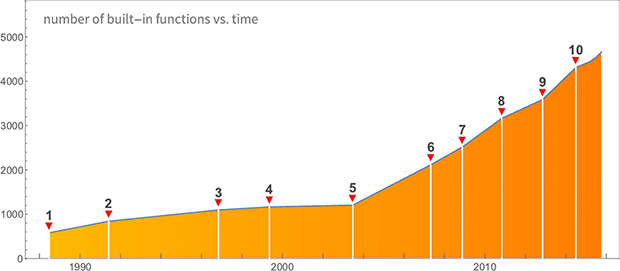

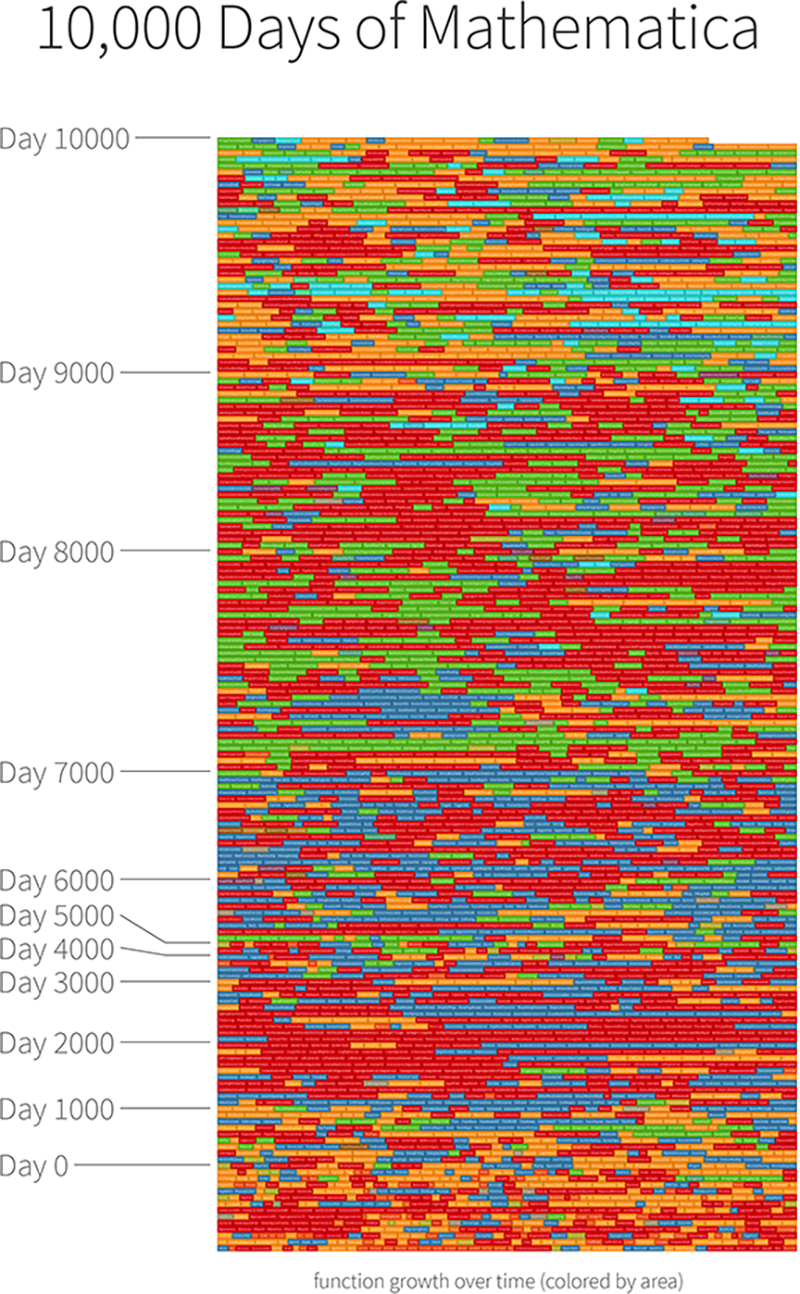

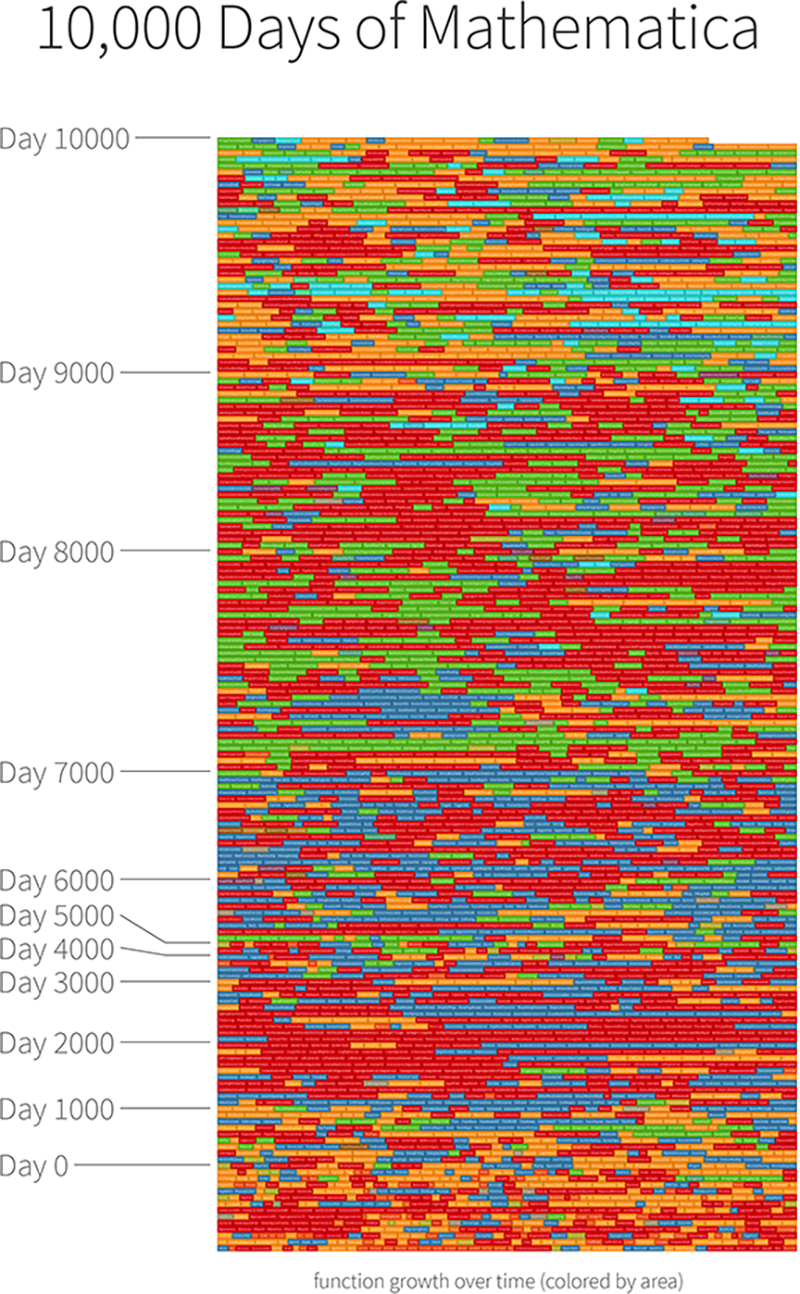

. , , Mathematica 10000 :

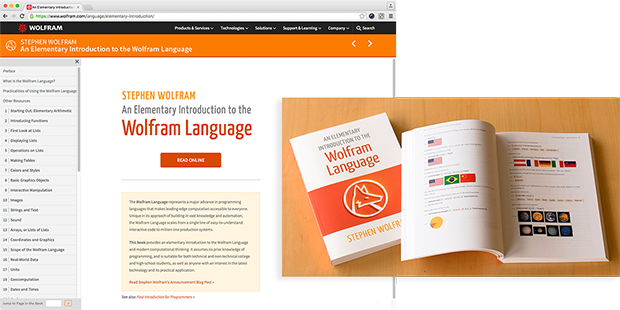

. , , : , . , :

Wolfram Open Cloud , Wolfram Language — 30 40 .

30 , Wolfram Language — , . — , .

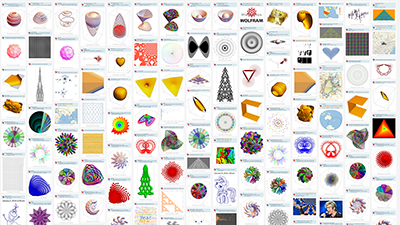

. , , . . , Tweet-a-Program :

— , Wolfram|Alpha , 15 Wolfram Language.

, Wolfram Language. , Wolfram Language . :

, , , 12-, Wolfram Language, Elliott 903. , .

, , , .

( . ):

Translation of the post by Stephen Wolfram (Stephen Wolfram) " My Life in Technology — As Told at the Computer History Museum ".

I express my deep gratitude to Polina Sologub for assistance in translating and preparing the publication.

Usually I am interested in the future. However, the story, in my opinion, is interesting and informative, and I also study it a lot. Most often this is the life story of other people. But the Computer History Museum asked me to tell you today about my own life and the technologies I created. That's what I'm going to do.

')

Now a unique time has come for me - a lot of things over which I worked for more than 30 years began to bear fruit.

My focus is on the Wolfram Language - a new kind of language based on knowledge (in which a huge amount of knowledge is embedded - both about computing and about the world as a whole). Wolfram Language is as automated as possible so that the path from the idea to the actual implementation is as short as possible.

Today I want to talk about how I was going to create the system Mathematica and Wolfram | Alpha .

I will have to talk a lot about my own history: mainly about how I spent most of my life doing science and technology. When I look back, much of what happened seems inevitable and implacable. And something I did not expect.

But let me start at the beginning. I was born in London in 1959 - so yes: I am godlessly old (at least by my current standards). My father ran a small company (international trade in textiles) for almost 60 years, and also wrote several science fiction novels . My mother was a professor of philosophy at Oxford . The last time I was at the Stanford bookstore, I accidentally saw her textbook on philosophical logic.

You know, I remember when I was 5 or 6 years old, I missed a party with a bunch of adults, and here’s a very long conversation about some very respected philosopher from Oxford ended with the words: “the day will come, and this child will philosopher . " Well, they were right. It's pretty funny that this happens.

That's how I was then:

I went to elementary school in Oxford - to a place called The School of the Dragon (I guess this is probably the most famous elementary school in England). Wikipedia believes that the most famous people in my class right now are me and the actor Hugh Laurie .

Here is one of my school reports (I was 7 years old). This is a class rating. So I excelled in poetry and geography, but not in mathematics (and yes, this is England, so we had the subject of “Bible study”). But at least it says: " he is full of spirit and determination; he must go far ... "

It was 1967, and I studied Latin and so on; but what I really liked was the future. At that time, the most future-oriented was the space program. And I became very interested and began to collect all the information I could find about each launched spacecraft, and the little notebooks, in which I saved all the information, put them together. And I found that even from England one could write to NASA and get all the material for free by mail.

At that time it was assumed that there would be colonies on Mars, and I began to make small projects for spacecraft.

I became interested in engines and ion batteries, and when I turned 11 years old, physics became my main interest.

And I found that you can learn a lot and quickly if you just read books (it had nothing to do with school). I chose various areas of physical science and tried to organize knowledge about them into a system. In the end (when I was already 12) I spent the summer, bringing together all the facts about physics. I suppose you could call some of this “visualization.” And, really, now it is, like so much more, easy to find on the Internet :

A few years ago, I found this again (at the time of the Wolfram | Alpha) and thought, “ Oh my gosh, I've done the same thing all my life! ” And then I started to dial numbers from those times when I was 11 or 12 years to see if Wolfram | Alpha does the same thing: Of course , everything worked:

When I was 12 years old, following the British tradition, I went to the so-called public school, although in fact it was private. I went to Eaton - the most famous of these schools, which was founded 50 years before Columbus arrived in America. I even received the highest scholarship among my children in 1972.

Yes, all the time they wore coats, and royal scholars like me also wore robes that protected from rain, etc. I thought I had successfully avoided these annual pictures in the style of Harry Potter, but once I was captured on group snapshot:

And at that time with his Latin, Greek and mantles I led a kind of double life, because my real passion was physics.

In the summer, when I turned 13, I gathered together brief information about particle physics :

And I made an important discovery: even a child can discover interesting things . And then I began to try to independently answer questions on physics or looked for answers in books, and by the time I turned 15, I began to publish articles on physics . No one asks how old you are when you send an article to a journal about physics.

When I was 12, something important happened: I met my first computer. This is Elliot 903C . This is not exactly the one I used, but similar:

He appeared at Eton along with my teacher Norman Routledge, who was a friend of Alan Turing . He had an 18-bit ferrite core on 8 kiloswords, programmed by means of a mylar tape, often on SIR (assembler).

Often it seemed that one of the most important skills was rewinding the tape after passing through an optical reader.

Anyway, I wanted to use a computer to do physics. When I was 12, I received this book :

I assumed that the image on the cover is simulated gas molecules, demonstrating increasing randomness and entropy. As is often the case, several years later I discovered that this picture was actually a kind of fake. But when I was 12, I really wanted to play it with a computer.

It was not so easy. The positions of the molecule should have been real numbers; it was necessary to have a collision algorithm, and so on. And, in order to adapt to the Elliott 903, I eventually simplified a lot - and came to what turned out to be a 2D cellular automaton.

Well, ten years after that, I made some big discoveries in the field of cellular automata . But then I was unlucky with my rule of the cellular automaton, and ended up doing it without finding anything. And in the end, my biggest achievement was writing bootable punched tapes for Elliott 903.

There is one serious problem with the mylar tape: it can get charged with static electricity and zazhevyvat holes, so the bits will be read incorrectly. Well, for my bootloader, I came up with error correction codes, and set them up so that if the check failed, the tape in the reader stopped, and you could pull it back a couple of meters to reread.

OK, so by the time I was 16, I published articles on physics and even became recognizable, left school and went to work at a British government laboratory called Rutherford Laboratory , which was involved in elementary particle research.

Now you may recall the school report card, from which it was clear that I was not very good at math. Things got a little better when I started using a slide rule, and then, in 1972, and a calculator. But I never liked doing math at school, or doing math in general. And there is a lot of mathematics in particle physics, so this dislike of mine was a problem.

Two things helped me in Rutherford's laboratory. First, a desktop computer with a plotter, on which I could do very beautiful interactive calculations. And, secondly, the mainframe for things that I programmed in Fortran.

After Rutherford's lab, I went to college at Oxford . For a very short time, I realized that this was a mistake, but at that time there was no need to attend lectures, so I just hid and did my research in physics. And basically I spent my time in a well-conditioned underground in the building of nuclear physics with terminals connected to a computer and ARPANET .

And just then - in 1976 - I first started using computers for practicing symbolic mathematics, algebra, and others. Feynman diagrams in elementary particle physics include a lot of algebra. And in 1962, it seems, the year three physicists met at CERN and decided to try using computers to work in this direction. They had three different approaches. One wrote a system called ASHMEDAI on Fortran . Another - under the influence of John McCarthy from Stanford - a system called Reduce in Lisp . And another wrote a system called SCHOONSCHIP on a CDC 6000 in assembly language with mnemonics in Dutch. Curiously, a few years later, one of these physicists won the Nobel Prize . It was Tini Veltman - the one who wrote SCHOONSCHIP in assembler .

In any case, in 1976, few people except the creators used these systems. I started using them all. However, my favorite was a completely different system, written in Lisp at MIT in the mid-1960s. It was a system called Macsyma . She worked on the Project MAC PDP-10 computer. And what was important to me as a 17-year-old child from England was that I could get to her on ARPANET.

There was a host 236. So I entered something like @O 236 and connected to an interactive operating system. Someone took the login SW. So I became Swolf and started using Macsyma.

I spent the summer of 1977 at the Argonne National Laboratory , where some of the ideas of physicists were tested in the room with the mainframe.

Then, in 1978, I went to a graduate student at the California Institute of Technology . I think that by this time I was the largest user of computer algebra in the world. And it was so great that I could figure out all these things so easily. I got great pleasure using ornate and complex formulas in my works.

I gained a reputation as a great calculator. Of course, she was 100% undeserved, because I did not think, but the computer. Although in reality (to be fair), something remained with me: doing calculations for so long, I earned a new kind of intuition. I did not take the integrals very well myself; but I could go back and get ahead with the computer, intuitively understanding what it was worth trying, and then running experiments to see what worked.

I wrote large chunks of code for Macsyma. And somewhere in 1979, I ran into a wall - something new was needed. Notice the ominous MACSYMA RELOAD line in the diagram.

Later, in November 1979 and shortly after my twentieth birthday, I collected some papers, called them a dissertation and received my doctoral degree . And a couple of days later I visited CERN in Geneva and began to think about my future in physics (as it seemed to me then). The only thing I was sure about at the time was that for my calculations I would need something besides Macsyma. That's when I decided to build a system to fit my needs. And I started to create a specification .

At first it was supposed to be ALGY - Algebraic Manipulator. However, I quickly realized that I must do much more than just algebraic manipulations. I knew most of the general-purpose computer languages like Algol , Lisp, and APL . But for some reason they did not capture the area in which I wanted to create my system.

I think I did what I learned from physics: I went deeper in order to find atoms and understand what was happening. I knew something about mathematical logic and the history of attempts to formulate something using logic, even when my mother’s textbook on philosophical logic did not exist.

The history of these attempts at formalization is very interesting and is associated with many well-known names: this is Aristotle and Leibniz (see the post on Habré " A detailed look at the legacy of Leibniz "), and Frege , and Peano , and Hilbert , and Whitehead , and Russell , and etc. But this is another conversation. However, in 1979, thoughts led me to the idea that I invented a structure based on the idea of symbolic expressions and their transformations.

What I got is what I called the SMP: Symbolic Manipulations Program , and I began to attract people from all over the California Institute of Technology to work on it. Richard Feynman was at meetings where I discussed the structure of my program and offered various ideas for interacting with the system. Meanwhile, the Faculty of Physics received a VAX 11/780, and after some wrangling, Unix was launched on it. At the same time, a young physics student named Rob Pike - the creator of the Go programming language - convinced me that I had to write code for my system in “the language of the future”: C.

I succeeded in writing C code, and for a while I wrote an average of about a thousand lines a day. And by June 1981, with the participation of several prominent personalities, the first version of SMP was ready - along with a large book of documentation that I wrote.

Good; You may ask: can we see SMP? When we worked on SMP, I had a brilliant idea that we should protect the source code with encryption. And, as you may have guessed, after three decades, no one could remember the password. Until some time ago there was one situation.

Implementing my other idea, I used a modified version of the Unix program for encryption to make more secure encryption. In honor of the 25th anniversary of the Mathematica system a couple of years ago, we implemented a crowdsourcing project on encryption cracking. Unfortunately, compiling the code was not an easy task - although with the help of a 15-year-old volunteer, we finally got something working.

And here it is: it works inside the VAX virtual machine emulator, so I can show (for the first time in 30 years) a running version of SMP.

SMP was a mixture of good and not-so-good ideas. For example, Tini Veltman, the author of SCHOONSHIP, suggested to me a bad idea: he proposed to represent rational numbers as a floating point, so that one could use faster floating-point instructions on several processors. However, there were many other bad ideas.

There were also interesting ideas - like those that I called “projections”: in fact, the union of functions and lists. With the exception of some troubles, they were wonderful. And something strange happened with almost all vectors with consecutive integer indices.

But overall, SMP worked very well, and I, of course, decided that it was a very useful thing. So now the next problem was to decide what to do with it. I realized that for such work a real team is needed, and the best way to get it is to transfer the business to commercial terms. However, at that time I was 21 years old, and I knew nothing about business.

Then I came to the university office of technology commercialization and asked them what to do. But it turned out that they did not know, because " mostly professors do not come to us; they open their own companies ." " Well, " I said, " can I do this? " And right there, the lawyer pulled out some kind of manual, looked into it and said: " it says that the copyright of the materials belong to their creators, and the software, too, so yes: you can do whatever you want ."

So I went out in order to try to create my own company. Although in the end it was not so easy, because the university suddenly decided that I should not have done what I wanted.

A couple of years ago, when I was at Caltech, I ran into a 95-year-old guy who was the rector at the time, and who finally filled out the rest of the details of what he called the " Wolfram case ." It was more strange than you can imagine. I will not talk about it. Suffice it to say that the story began with Arnold Backman , a post-doc from 1929 from California Technological, who claimed his rights to the pH meter and founded Beckman Instruments - and then, in 1980, being chairman of the board of trustees of the same institute, he was upset about for having discovered genetic sequencing technology at Caltech, and left to create Applied Biosystems .

The company I created has withstood a storm, even if I finally left the California Institute of Technology, which, in turn, did away with the strange software ownership policy, which has long influenced their efforts to find personnel in the computer industry.

Having founded Computer Mathematics Corporation , I did nothing grand. I invited a person (who was twice my age) to the position of CEO. And pretty quickly everything began to go away from what I thought made sense.

One of my favorite moments of madness was the idea to get into the equipment business and build a station to launch SMP. Well, at that time no station had enough memory, and the virtual memory was not supported in the Motorola 68000 processor. , 68000-x , , , . , . , , — SUN — .

, 1981 , , , — — . , , , , Inference Corporation ( NASDAQ). SMP , - 40 000$ . , , .

— , , , " ", .

— - , . , — (SUN) ( — ):

- — ; — , . Thinking Machines Corporation . , WarGames , : " , ? ". Connection Machine , .

, (" ") , Ixis. , , . , , , (, ) , .

. ( ), , . , " Microsoft ". Microsoft.

1985 , , , . -, - , . , - .

— , . — , , Beckman Foundation, . , 1986 , - 100 .

, . , . , .

. , , , , . : -, ; , -, .

. SMP. C. PostScript , . , . , , , , .

, , . SMP , , — , , Mathematica .

, , . , , ,— . Mathematica , SMP. SMP — Mathematica , .

, Mathematica . Omega . . Polymath . Technique . — . , , ( - ) .

, . - , Adobe PostScript. , , , , , NeXT .

. , , " Mathematica ", , . , — . .

18 Mathematica. , . , , .

Mathematica NeXT :

: Sun — ; Silicon Graphics . Ardent — . AIX/RT ( IBM ) — .

: 23 1988 .

Mathematica: . Addison-Wesley , . , PostScript , . , , , Addison-Wesley.

Mathematica — , , Techmart, -. Mathematica MS-DOS - (640). , Mac. ComputerWare — -.

. , . Apple . Sun , :

Mathematica. Mathematica — , Mathematica. , — , , - .

. . . , Time " Those Computers Are Dummies ", Mathematica .

Mathematica . — , , Sony , .

. Cray-2 . Mathematica . - 2 + 2. — — «5». , .

- 1990 — :

NeXT Mathematica . , , NeXT Mathematica. - , .

, - 150 . : , - , ? , ; , . , — — .

— , . , Mathematica . , . , — .

. , . 10 . , … , !

, , , — . . .

, 7 1994 :

, :

1996 Mathematica. 1988 . Mathematica . , . 1989^1989 — , 1989 , . Raspberry Pi , .

, 1988 ( , , , ) Mac NeXT, .

, - Mathematica. C (- C, , C ++ 1988 ). Mathematica, Wolfram Language — .

, , . — Mac, NeXT, Microsoft Windows X Windows. 1996 . 20 ; , .

Mathematica - , .

« », MathMobiles , .

Mathematica . , , . , 1997 Mathematica. , : , . , - — Mathematica. .

. DRM : " PC; Mathematica ! ". : " ". , , .

2002 , , , , :

" " , . , , , . , . , , , .

Mathematica, . , . 2006 , ( ). CDF ( ), Wolfram Demonstrations .

. . . , . , 36 , The Wolfram Functions Site 300,000+ :

, . , , , . -, . .

, , . . webMathematica , , …

Mathematica , , .

, , , , " ": -, . , - . 1980 , . .

, . " " " " . , , , " ", .

, , Mathematica. : " , , ? " , . : " - " . . , , .

. , , . — , . , . , .

, , . , WolframTones. , . , . . Wolfram|Alpha — , .

, , Wolfram|Alpha . , , - , , .

, Wolfram|Alpha ( Mathematica Wolfram Language) . , .

, 15 2009 . : , . Amazon -: , .

. , , . . , - , - , , , , , , , . , justin.tv ( YCombinator ), — .

« » , , . , : , .

, . , . , — , .

, , . . : ! Wolfram|Alpha ( ):

, , . , , 9:33:50 15 2009 , Wolfram|Alpha . . , .

. , - :

- : « , ?! ". — :

Wolfram|Alpha; . Microsoft Wolfram|Alpha Bing . Siri . Apple Siri, ( ) Wolfram|Alpha Siri.

, . Wolfram Language . , . 1990- Mathematica — M Language. , : , , 1993 . , .

. , Wolfram|Alpha, , . , , , Mathematica . :

, 90% . " ", . , - . , Wolfram|Alpha , .

- — , , — .

Mathematica , . Wolfram Language ( ) — , — . …

. , , Mathematica 10000 :

. , , : , . , :

Wolfram Open Cloud , Wolfram Language — 30 40 .

30 , Wolfram Language — , . — , .

. , , . . , Tweet-a-Program :

— , Wolfram|Alpha , 15 Wolfram Language.

, Wolfram Language. , Wolfram Language . :

, , , 12-, Wolfram Language, Elliott 903. , .

, , , .

( . ):

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/308728/

All Articles