Graphical user interface as a reflection of the real world: the shadows and the rise of elements

When developing GUIs, they are now trying to gradually get rid of everything superfluous and focus on functionality. But although functionality is one of the key factors for the success of a product, the visual component is just as important - especially because it can improve functionality.

')

In this article, I will show how visual elements, such as shadows, can carry information that is perceived by the user interface.

Interface evolution: from pseudo-three-dimensional to ultra-flat design

Three-dimensional effects and skevomorphism: the illusion of the depth of the interface

Although the displays became almost flat, designers and developers did a lot to make their content appear three-dimensional. Since the inception of graphical interfaces, pseudo-three-dimensional effects (shadows, gradients, selection) have been used in them - helping the user at a glance to understand how to interact with one or another element. Such effects created the illusion of depth, informed the user about the position of the elements in the hierarchy, and also indicated their interactivity. Among other things:

· Items that seem raised look like they can be pressed. So often denoted buttons.

· Items that seem to be depressed (or empty) look like they can be filled. This is often referred to as input fields.

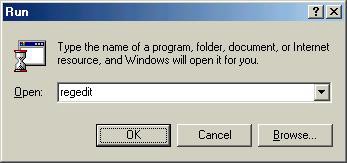

The Windows 95 dialog box below illustrates how using shadows and highlighting can create 3D effects.

Notice that the buttons appear raised and the input field is depressed.

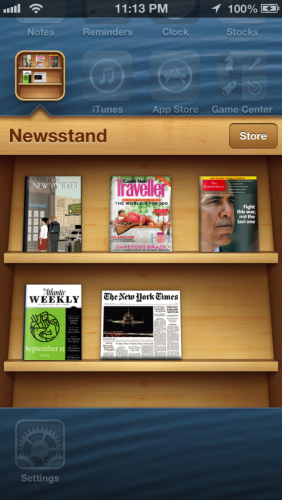

Skevomorphism was the next stage in the evolution of this idea: now the interface elements imitate objects of the real world, transferring them to the digital world. Skevomorphism in the digital world is often associated with Apple products (especially with iOS before version 7). They really are a great example of how ske-morphism looks in digital design. Take for example the application Newsstand. It uses a skevomorphic bookcase with three “shelves” and wood textures. The metaphor of the bookcase should help users quickly learn how to interact with the application.

Newsstand on iOS6. Drop shadows and background textures — tools that simulate real-world objects

And yet, early attempts to create three-dimensional and the use of skeuomorphism often made interfaces too cumbersome — they were overloaded with elements, and the implementation details distracted from the functional.

Flat design: removing shadows reduces potential for mastering the interface.

For every action there is a reaction. So in the world of digital design, there was opposition to skevomorphism. The idea was this: no matter how hard we try, the screen content will never look truly three-dimensional, so why not get rid of all this tinsel and focus on functionality?

Unlike three-dimensional design or skeuomorphism, a truly flat design does not even try to reproduce the appearance of objects in the real world. The elements in it are really flat. No lighting model, not even light shadows, that would indicate that the element is pushed (because it’s as if lifted above the others) or filled (because it’s as if pressed into the surface).

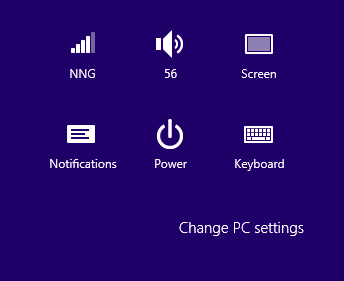

Take, for example, the Microsoft Metro design language in Windows 8.

Windows 8 interface - an example of super-flat design

Extremely opposite: everything seems too flat. The “Change PC Settings” element looks more like a label for this group of icons than a button. As a result, many users never use it, even without realizing that it exists. When an element is simply out of sight or its function is misunderstood, the reason for this is the poor distinguishability of the element and the action associated with it.

For decades, interface designers have been making objects so detailed for a reason. All that was abandoned in the super-flat design - reflections, the effect of elevation in the buttons or indentation in the input fields, that is, a variety of highlighters - were designed to indicate the possibility of interaction with the element. And although the specific means by which this feature was indicated varied from application to application, users could always assume that:

- Clearly selected items can most likely be clicked;

- Elements without a clear selection, most likely, can not be clicked.

Before and after the introduction of a flat design - the almost complete absence of elements with a clear selection does not allow to determine exactly which objects are pressed

For this reason, a complete rejection of any means of distinguishing elements according to their functionality is clearly a bad decision. Users need highlighters - indicators by which you can instantly understand what is clicked on a page or in an application. Among other things, the extremely important indicator on which the human brain relies are the shadows.

Almost flat design

Recently, designers have begun to understand the problems with flat usability with usability. As a result, more balanced solutions have emerged, sometimes called the “almost flat design” or “flat design 2.0”. In style, they are almost flat, but use light shadows, highlights and layers to give the interface depth.

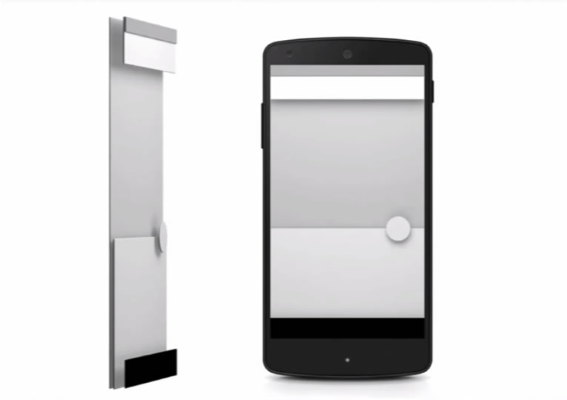

Designed by Google, Material Design is a good example of this almost flat design. It uses physical principles to give the interface meaningful and visually streamline elements. Simplified, Material Design does not sacrifice highlighters.

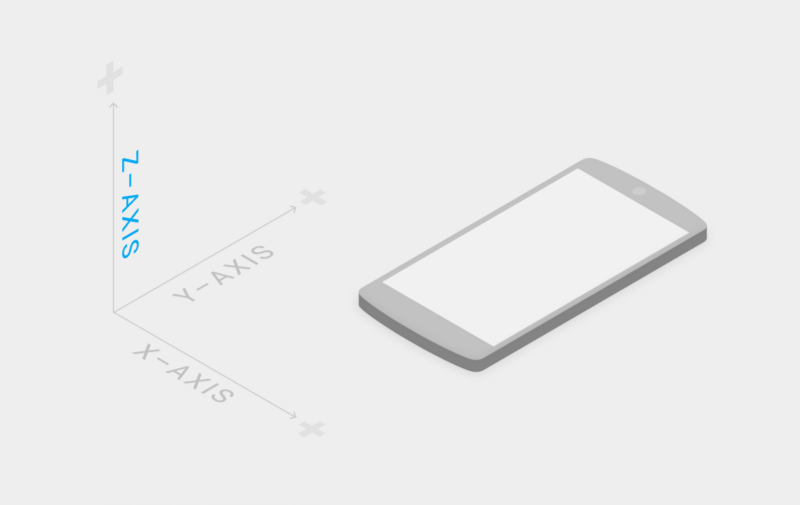

Android GUI Depth

Shadows and lifting elements

Modern interfaces are more multi-layered and take full advantage of the Z axis, that is, depth. This approach makes them more “tangible”.

The feeling of depth is created by shadows - elements and images that cast shadows look like they hover over a page. Shadows slightly “season” the design, but they also do not make it too “cloying”. They do not distract the user, on the contrary - thanks to them he can understand that:

- Drop shadow element can be clicked.

- If one element casts a shadow on another, then the first one is higher - this allows you to arrange the elements, creating a hierarchy.

Before and after - if it were not for the shadow, it would be impossible to understand that the pink circle and the blue surface are separate elements

- Shadows also make it clear in which direction the object has moved.

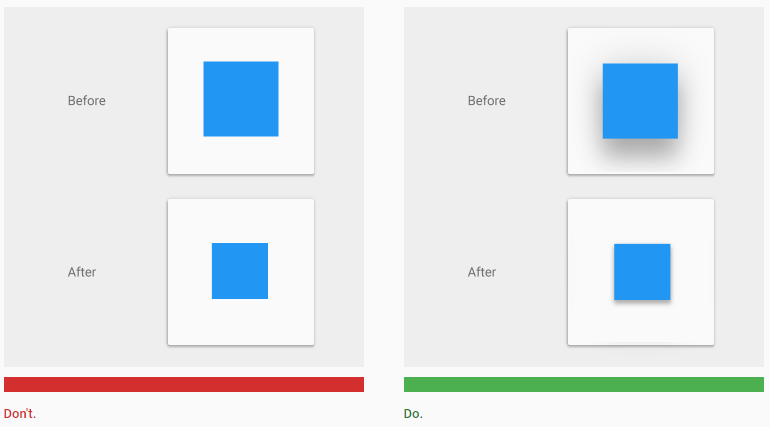

Before and after - the shadow cast is reduced and becomes clearer or enlarged and blurred as the object is lowered or raised.

- Shadows are used in conjunction with lifting elements. Rise is the relative depth (or height), the distance between two surfaces along the Z axis. Rise is measured from the top of one element to the top of another and determines the depth of the shadow that the first one casts on the second.

Different lifting values of two objects in Material Design

If the user is not sure whether the item is clickable or not, he should understand this by the changes that occur after clicking. Here comes the rise. When the rise of an element changes, its shadow also changes:

Button rises after pressing

The card rises after activation

Conclusion

In design, you should not rely on hard shadows, excessively variegated gradients or complex lighting effects - all this can distract the user from the designation of elements.

However, soft shadows and other means of “non-planar” interfaces can be useful - they carry important information, highlighting objects and denoting their functionality and state.

Users prefer simplicity, clarity and orderliness - and when designing interfaces, one should rely on the peculiarities of human perception. Examples of successful interfaces that have emerged in recent years show that the one who brings the underlying principles of design to perfection wins.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/306626/

All Articles