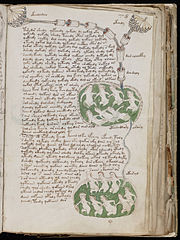

Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich Manuscript (Eng. Voynich Manuscript) is a mysterious book written about 500 years ago by an unknown author, in an unknown language, using an unknown alphabet.

The Voynich Manuscript (Eng. Voynich Manuscript) is a mysterious book written about 500 years ago by an unknown author, in an unknown language, using an unknown alphabet.Manuscript Voynich tried to decipher many times, but so far without any success. She became the Holy Grail of cryptography, but it is not at all possible that the manuscript is only a hoax, an incoherent set of characters.

The book is named after the American bookseller of Lithuanian origin, Wilfried Voinich (the husband of the famous writer Ethel Lilian Voinich, author of Gadfly), who acquired it in 1912. It is now stored in the Beinecke Rare Book And Manuscript Library of the Yale University.

')

Description

The book has about 240 pages of fine parchment. There are no inscriptions or drawings on the cover. The size of the page is 15 by 23 cm, the thickness of the book is less than 3 cm. Gaps in the page numbering (which is probably younger than the book itself) indicate that some pages were lost by the time the book was acquired by Wilfried Voinich. The text is written by a bird feather, he also made illustrations. The illustrations are coarsely painted in color, perhaps after writing the book.

Illustrations

IllustrationsWith the exception of the final part of the book, there are pictures on all pages. Judging by them, there are several sections in the book, different in style and content:

"Botanical". On each page there is an image of one plant (sometimes two) and several paragraphs of the text - the manner usual for the books of European herbalists of that time. Some parts of these figures are enlarged and clearer copies of sketches from the “pharmaceutical” section.

"Astronomical". It contains round charts, some of them with the moon, sun and stars, presumably astronomical or astrological content. One series of 12 diagrams depicts the traditional symbols of the zodiacal constellations (two fish for Pisces, a bull for Taurus, a soldier with a crossbow for Sagittarius, etc.). Each symbol is surrounded by exactly thirty miniature female figures, most of which are naked, each of them holds an inscribed star. The last two pages of this section (Aquarius and Capricorn, or, relatively speaking, January and February) were lost, and Aries and Taurus were divided into four paired diagrams with fifteen stars each. Some of these diagrams are located on embedded pages.

"Biological". Dense inseparable text, wrapping images of bodies, mainly naked women bathing in ponds or ducts connected by a meticulously thought-out pipeline, some "tubes" clearly take the form of body organs. Some women have heads on their heads.

"Cosmological". Other pie charts, but incomprehensible meaning. This section also has embedded pages. One of these six-page attachments contains a kind of map or diagram with six “islands” connected by “dams” with castles and, possibly, a volcano.

"Pharmaceutical". A set of signed drawings of parts of plants with images of pharmaceutical vessels on the margins of pages. There are also a few paragraphs of text in this section, possibly with recipes.

"Prescription". A section consists of short paragraphs separated by flower-like (or star-shaped) marks.

Text

TextThe text is definitely written from left to right, with a slightly “ragged” right margin. The long sections are divided into paragraphs, sometimes with a mark of the beginning of a paragraph in the left margin. There is no usual punctuation in the manuscript. The handwriting is steady and rosary, as if the alphabet was familiar to the scribe, and he understood what he was writing.

The book contains more than 170,000 characters, usually separated from each other by narrow spaces. Most signs are written with one or two simple pen movements. The alphabet of 20-30 letters of the manuscript, you can write the whole text. The exception is a few dozen special characters, each of which appears in the book 1-2 times.

Wider spaces divide the text into about 35 thousand "words" of various lengths. It seems that they obey some phonetic or spelling rules. Some signs must appear in each word (like vowels in English), some signs never follow others, some may double in a word (like two and a long word), some do not.

Statistical analysis of the text revealed its structure characteristic of natural languages. For example, the repetition of words corresponds to Zipf's law, and the dictionary entropy (about ten bits per word) is the same as in Latin and English. Some words appear only in separate sections of the book, or only on several pages; Some words are repeated throughout the text. There are very few repetitions among about a hundred signatures to the illustrations. In the "Botanical" section, the first word of each page is found only on this page and, perhaps, is the name of the plant.

On the other hand, the language of the Voynich manuscript is somewhat quite unlike the existing European languages. For example, in the book there are almost no words longer than ten "letters" and almost no one- and two-letter words. Inside the word, the letters are also distributed in a peculiar way: some characters appear only at the beginning of the word, others only at the end, and some are always in the middle — the arrangement is inherent in the Arabic letter (cf. also variants of the Greek letter sigma), but not in the Latin or Cyrillic alphabet.

The text looks more monotonous (in the mathematical sense) compared with the text in the European language. There are some examples where the same word is repeated three times in a row. Words that differ only in one letter are also found unusually often. The whole "lexicon" of the Voynich manuscript is less than what a normal book should be.

Story

StorySince the manuscript alphabet has no visual similarity with any known writing system and the text has not yet been deciphered, the only “hook” for determining the age of the book and its origin is illustration. In particular, - clothes and decoration of women, as well as a pair of locks on the charts. All the details are typical for Europe between 1450 and 1520, so the manuscript most often dates from this period. This is indirectly confirmed by other signs.

The very first known owner of the book was Georg Baresch, an alchemist who lived in Prague at the beginning of the 17th century. Bares, apparently, was also puzzled by the secret of this book from his library. Upon learning that Athanasius Kircher, a famous Jesuit scholar from the Roman College (Collegio Romano), published a Coptic dictionary and deciphered (as it was thought) Egyptian hieroglyphs, he copied part of the manuscript and sent this sample to Kircher in Rome (twice), asking help decipher it. The letter of Baresh in 1639 to Kircher, discovered already in our time by Rene Zandbergen - the earliest known mention of the Manuscript.

It remains unclear whether Kircher responded to Baresh’s request, but it is known that he wanted to buy the book, but Baresh probably refused to sell it. After the death of Bares, the book passed to his friend Johannes Marcus Marci, the rector of Prague University. Marci allegedly sent her to Kircher, his longtime friend. His cover letter of 1666 is still attached to the Manuscript. Among other things, the letter states that it was originally bought for 600 ducats by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Rudolph II, who considered the book to be the work of Roger Bacon.

The subsequent 200 years of the fate of the Manuscripts are unknown, but it is most likely that it was kept with the rest of Kircher's correspondence in the library of the Roman Collegium (now the Gregorian University). The book probably remained there until the troops of Victor Emmanuel II seized the city in 1870 and annexed the Papal State to the Italian Kingdom. The new Italian authorities decided to confiscate a large amount of property from the Church, including the library. According to Xavier Ceccaldi and others, many books from the university library were quickly transferred to libraries of university staff whose property was not confiscated. Kircher's correspondence was among these books, and also, obviously, there was the Voynich manuscript, as until now the book bears the ex-libris of Petrus Beckx, then the head of the Jesuit order and the rector of the university.

The Bex library was moved to Villa Mondragon in Frascati (villa Borghese di Mondragone a Frascati) - a large palace near Rome, acquired by the Jesuit society in 1866.

In 1912, the Roman College needed money and decided to sell a part of its property in the strictest confidence. Wilfried Voinich purchased 30 manuscripts, among other things, the one that now bears his name. In 1961, after the death of Voinich, the book was sold by his widow Ethel Lilian Voinich (author of Gadfly) to another bookseller, Hanse Kraus. Not finding a buyer, in 1969, Kraus presented the manuscript to Yale University.

Guessing about authorship

Many people are credited with the authorship of the Voynich manuscript. Next are a few common guesses.

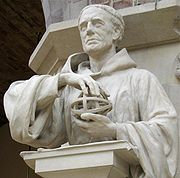

Roger Bacon

Roger BaconThe covering letter of Marci Kircher of 1665 states that, according to the words of his deceased friend Raphael Mnishovsky, the book was at one time purchased by Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) for 600 ducats (several thousand dollars for modern money). According to this letter, Rudolph (or perhaps Raphael) believed that the author of the book was the famous and versatile talented Franciscan monk Roger Bacon (1214-1294).

Although Marzi wrote that he was “refraining from judging” (suspending his judgment) about the statement of Rudolph II, but it was taken seriously enough by Voynich, who rather agreed with him. His conviction strongly influenced most decryption attempts over the next 80 years. However, researchers who were engaged in the Voynich manuscript and are familiar with the works of Bacon, strongly deny this possibility. It should also be noted that Raphael died in 1644 and the deal was to take place before the abdication of Rudolph II in 1611 - at least 55 years before Marci’s letter.

John dee

The assumption that Roger Bacon was the author of the book led Wojnicz to the conclusion that the only person who could sell the Rudolf manuscript was John Dee, a mathematician and astrologer at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, also known for having a large library of Bacon’s manuscripts . Dee and his scrier (assistant medium using a crystal ball or other reflective object to call the spirits) Edward Kelly is associated with Rudolf II by living in Bohemia for several years, hoping to sell his services to the emperor. However, John Dee kept a careful diary, where he did not mention the sale of the Rudolf manuscript, so this deal seems rather improbable. Anyway, if the author of the manuscript is not Roger Bacon, then the possible connection between the history of the manuscript and John Dee is very slim. On the other hand, Dee himself could write a book and spread rumors that this was Bacon’s work, hoping to sell it.

Manuscript Language Theories

Many theories have been advanced about the language used by the manuscript. The following are some of them.

Letter cipher

According to this theory, the Voynich manuscript contains a meaningful text in some European language, which was deliberately translated into an unreadable form by displaying it in the alphabet of a manuscript using some kind of encoding - an algorithm that operated on in separate letters.

This was a working hypothesis for most decrypting attempts during the 20th century, including the unofficial group of cryptanalytics of the National Security Agency (NSA) led by William Friedman in the early 1950s. The simplest ciphers, based on the replacement of characters, can be excluded, since they are very easy to crack. Therefore, the efforts of the decoders were directed to the polyalphabet ciphers invented by Alberti in the 1460s. This class includes the well-known Vigenere cipher, which could be enhanced by using non-existent and / or similar characters, rearranging letters, false spaces between words, etc. Some researchers assume that vowels have been removed before being encoded. There were several declarations of decryption based on these assumptions, but they were not widely accepted. First of all, because the proposed decoding algorithms were based on so many guesses that with their help one could extract meaningful information from any random sequence of characters.

The main argument in favor of this theory is that the use of strange characters by a European author can hardly be explained otherwise than by trying to hide information. Indeed, Roger Bacon understood ciphers, and the estimated period of the creation of the manuscript approximately coincides with the birth of cryptography as a systematized science. This theory is opposed by the observation that the use of a poly-alphabetic cipher should have destroyed the “natural” statistical properties that are observed in the text of the Voynich manuscript, such as Zipf's law. Also, although the poly alphabetic cipher was invented around 1467, its varieties became popular only in the 16th century, which is somewhat later than the estimated time of writing the manuscript.

Codebook Code

According to this theory, words in the text of a manuscript are actually codes that are deciphered in a special dictionary or code book. The main argument in favor of the theory is that the internal structure and distribution of word lengths are similar to those used in Roman numerals, which would be a natural choice for this purpose at that time. However, codebook based coding is only satisfactory when writing short messages, as it is very burdensome for writing and reading.

Visual cipher

James Finn suggested in his book “The Hope of Pandora's Hope” (2004) that the Voynich manuscript is actually a visually coded Hebrew text. After the letters in the manuscript have been correctly transcribed into the “European Voynich Alphabet” (EAB, or EVA in English), many words in the manuscript can be represented as Hebrew words that are repeated with different distortions to mislead the reader. For example, the word AIN from a manuscript is the word "eye" in Hebrew, which is repeated as a distorted version in the form of "aiin" or "aiiin", which gives the impression of several different words, although in reality it is the same word. The possibility of using other methods of visual coding. The main argument in favor of this theory is that it can explain the unfortunate outcomes of other decoding attempts that relied more on mathematical decryption methods. The main argument against this point of view is that with such an approach to the nature of the cipher of the manuscript, the burden of a single decoder falls on the heavy burden of different interpretations of the same text due to the many alternative possibilities of visual coding.

Micrography

After being re-discovered in 1912, one of the earliest attempts to uncover the secret of the manuscript (and undoubtedly the first among the premature decoding statements) was made in 1921 by William Newbold, a renowned expert in cryptanalysis and a professor of philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania of Pennsylvania), as well as a collector of old books. His theory was that the visible text is meaningless, but each character that makes up the text is a collection of tiny lines that can only be distinguished by magnification. These dashes supposedly formed the second level of reading the manuscript, which contained a meaningful text. In this case, Newbold relied on the ancient Greek method of cursive writing, which used a similar system of symbols. Newbold argued that, on the basis of this premise, he was able to decipher a whole paragraph that proved Bacon’s authorship and testified to his outstanding scientist abilities, in particular his use of a complex microscope four hundred years before Anthony van Leeuwenhoek.

However, after Newbold's death, cryptologist John Manly from the University of Chicago (University of Chicago) noted serious flaws in this theory. Each dash contained in the characters of the manuscript allowed several interpretations in decoding without a reliable way to reveal the “correct” version among them. The method of William Newbold also required a rearrangement of the “letters” of the manuscript until a meaningful text in Latin was obtained. This led to the conclusion that using the Newbold method one could obtain almost any desired text from the Voynich manuscript. Manley argued that these lines appeared as a result of ink cracking when they dried on coarse parchment. At present, Newbold's theory is hardly considered when deciphering a manuscript.

Steganography

, , , , , , . . , , (Johannes Trithemius) 1499. , - . , - . , — - .

, . , , ( ), . , , , .

(Jacques Guy) , , . , - (, , ), (, ) , , (, .). «» ( ) , , ( ).

. , , , . , , . , , — XIII , 1499 . , .

, , , ( , ). , (, -), . — , , . , 360 ( 365), 15 , — . , ( ) .

2003 (Zbigniew Banasik) , . :

* www.dcc.unicamp.br/~stolfi/voynich/04-05-20-manchu-theo

* www.voynich.net/Arch/2004/05/msg00187.html

* www.voynich.net/Arch/2004/05/msg00195.html

« : , » (Solution of the Voynich Manuscript: A liturgical Manual for the Endura Rite of the Cathari Heresy, the Cult of Isis) 1987 , (Leo Levitov) , — « ». « , , , , ». .

, , — - : , ( ). , - , . , , , — . , , .

. — , , , , . , XII XIII , , . .

«» (John Tiltman), , , , « ». , , , . , (Ro), «bofo-» , bofo- , bofoc, bofof. , , ( ), , «» , «» , «» . .

, « » 1668 (John Wilkins). , , , . , , , , . . . , , , , , XVII .

( ) ( , ) , .

2003 (Gordon Rugg), () , : , , «». . , , 1550 (Girolamo Cardano), . , , , , . , . «», ( ) , , , . .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/30488/

All Articles