Super Mario World Method: Add-ons and Extensions

This is a continuation of the first lesson on using the Nintendo method to create levels . Working on the Super Mario World game, the Nintendo development team has created (possibly, intuitively) a very effective method of building levels and organizing their content. I call this method Test, Modulation, Series of Obstacles, or IMSP.

In the previous lesson, we looked at the concepts of test and modulation. If you have not had the opportunity to get acquainted with the first part, I recommend to do it, otherwise it will be incomprehensible to you. In this tutorial, we’ll talk more about how to use add-ons and extensions.

Although IMSP is a means of organizing content when creating levels, this method in no way limits the creative potential of the designer. I will show you how it can be used to get the maximum effect with a limited set of tools for building levels.

')

I created a demo level that shows how to form a sequence of various trials with varying complexity using a total of 6 different opponents or obstacles. Next, we analyze all the components of this level:

Level ID: 1288 0000 00EC F5A2

In the first seven tests of this level, the addition method is used. As you can remember from the first article, the supplemented test is qualitatively more complicated than the previous one, but on the whole retains its idea.

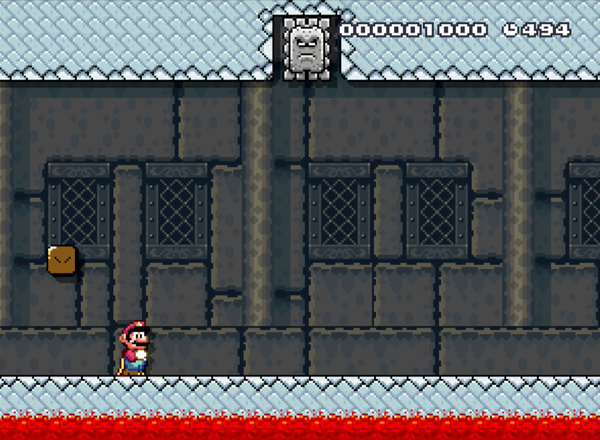

Let's see how it works in this situation. Here is the first test:

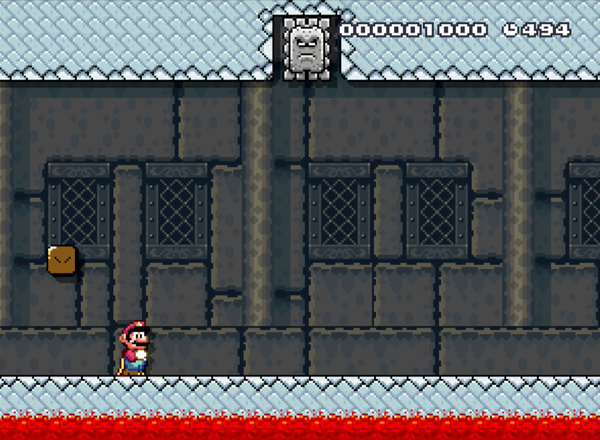

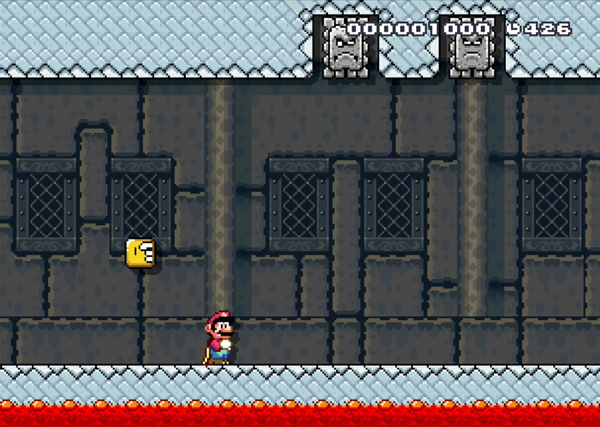

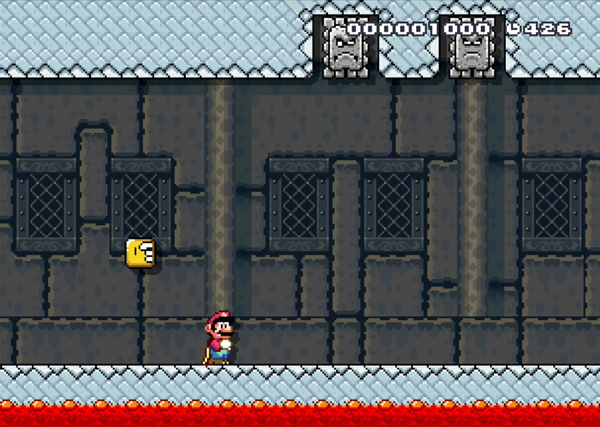

We have before us an ordinary Twomp who tries to crush Mario every time he gets too close. The idea is quite simple, and the addition to it is also not difficult.

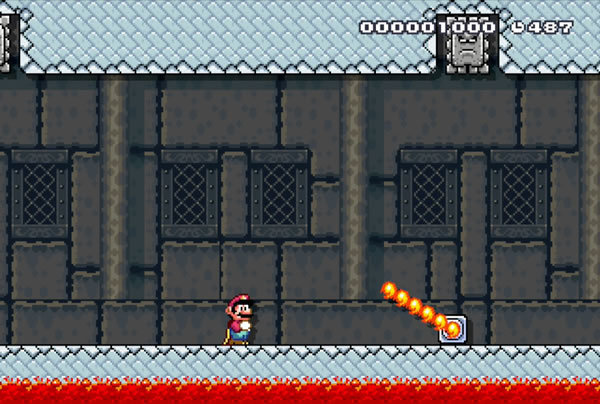

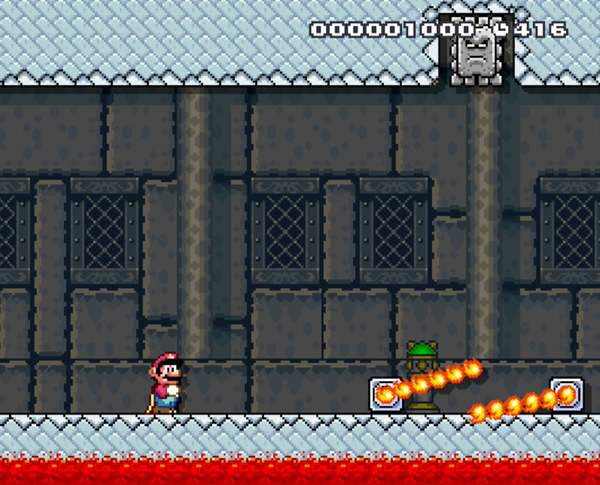

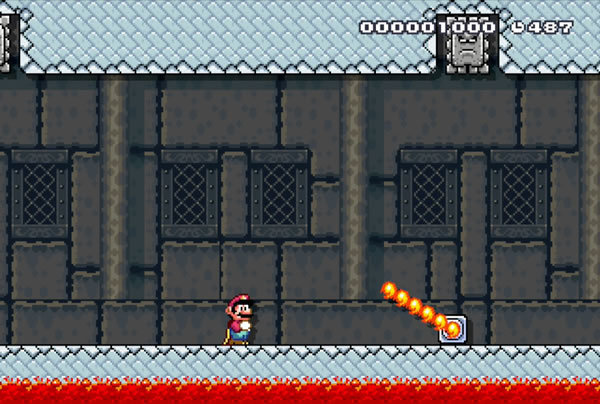

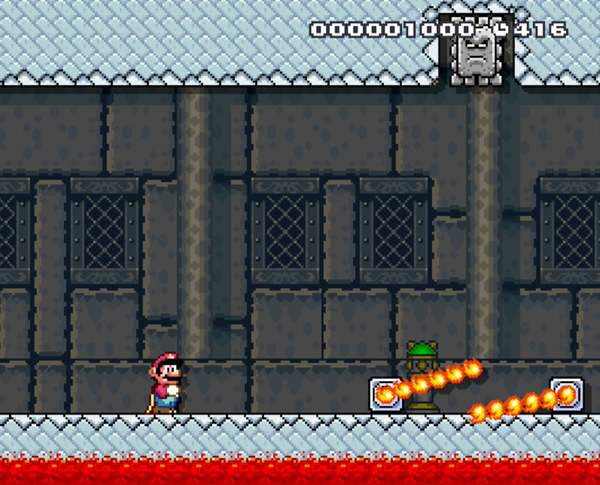

I added a fire barrier, and now the player must jump over it, instead of just running forward.

Adding one element to another is the most basic form of an add-on. The dynamics are simple: the test becomes more difficult when more obstacles appear in it. But it can also be part of an even more difficult test.

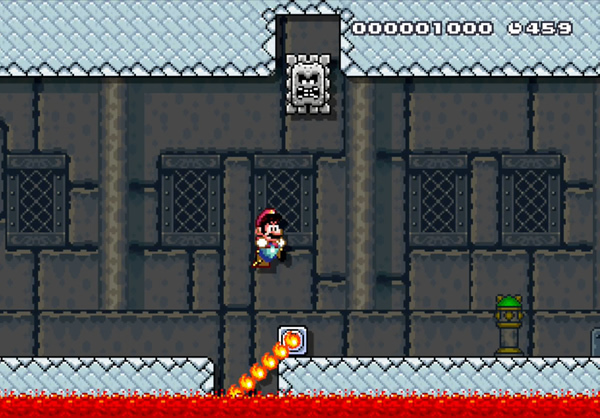

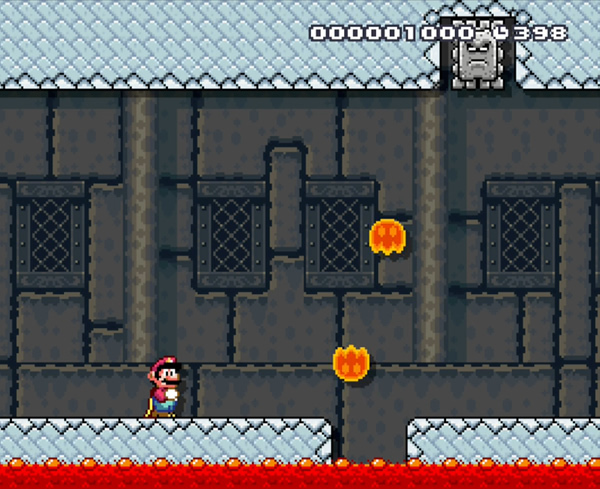

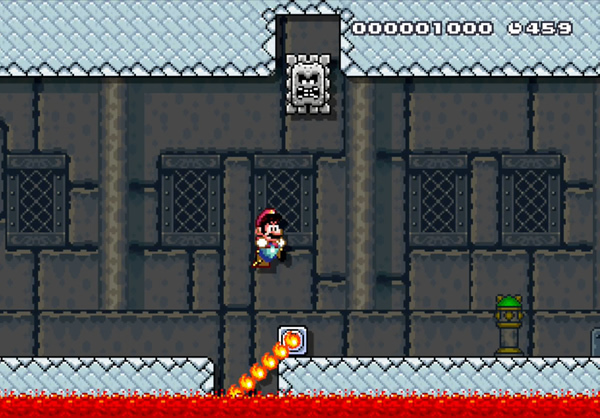

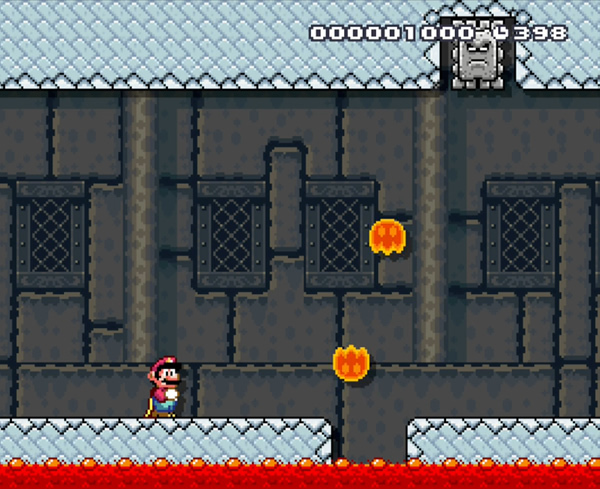

In the following example, I added a new obstacle - the abyss to the left of Twomp.

She doesn’t just force the player to make the jump - she makes him jump right under Twomp’s blow. As you can see, this addition is not much more complicated than the previous one - which is quite normal. Both of these additions are simply branches of the very first test.

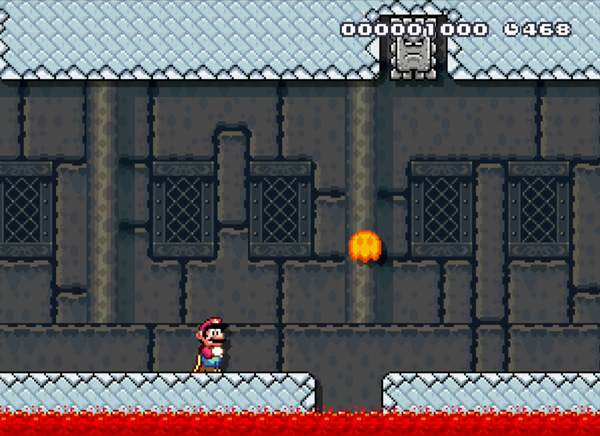

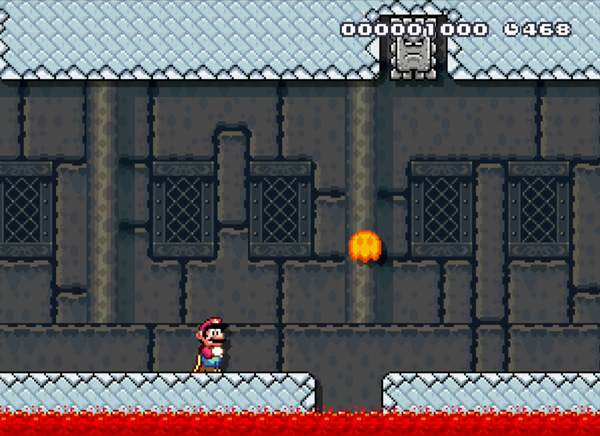

Next, I decided to introduce an addition to the abyss: I added a fireball that shoots at regular intervals. Now the player must wait for the right moment to jump over the abyss and dodge Twomp. This also complicates the previous test - however, still not much.

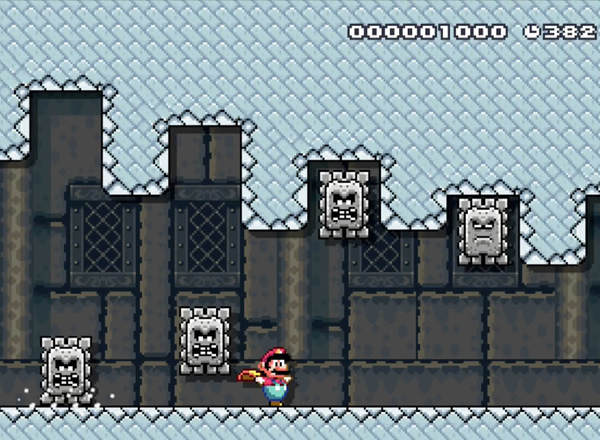

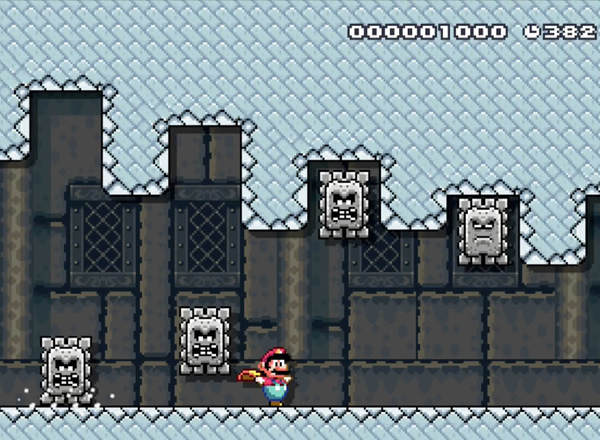

In the following test, I will combine everything that we have used so far:

So far this is the most difficult test: there are 3 obstacles in it at once. In Nintendo games, you rarely find more than three obstacles at a time. This example is really difficult and more or less corresponds to the most difficult trials in games from Nintendo. Of course, you can go further in your game (or in your Mario Maker levels); I am just showing the principle.

In the next two trials, I decided to slightly reduce the complexity and focus on the qualitative changes. Please note: the difficulty levels in the game should not always increase linearly. The complexity may decrease and increase - sometimes it is enough to make the tests diverse, and not more and more difficult.

Given this fact, I removed the chasm and added Chein Chomp instead.

And then I returned the abyss with a ball of fire, but removed the fire barrier.

All these tests are quite complex, but they do not pile up obstacles without stopping. There is a limit to the number of elements added to the test, after which the game ceases to be fun and begins to annoy. But this limit depends on the context.

Before turning to the most important conclusion concerning the supplements, I would like to highlight the correct use of extensions. In the previous article, I defined the extension as an addition, but with quantitative (and not qualitative) changes from the previous test. Consider a simple example:

This is the first extension. We returned to the very first test level and simply doubled the number of Twomp.

What is the relationship between quantitative changes and perceived complexity? Despite the double number of Twomp, the player will hardly make more effort passing it.

Extensions have one important principle: they change the complexity of the test is not linear. Extensions also depend on the context, as well as additions, despite their fundamental differences.

Another example of expansion:

The double number of fire barriers, in contrast to the double number of Twomp, significantly complicates the test (especially due to their asynchronous rotation). In principle, this test can be called the most difficult at all levels. It turns out that we are dealing with exactly the same type of expansion as before, but the experience is completely different.

And what if to apply this reception to other element? For example, to the width of the abyss:

This type of extension is a little harder to recognize. I decided to increase the width of the abyss to two blocks instead of one (that is, double it, like all the elements before), so that the player could feel the difference in the length of the jump, even if he did not immediately see it.

Interesting, but again this slightly increases the difficulty of the test. The fact is that before the player had to select the optimal angle of landing, in order to jump over the abyss, without being hit by Twomp.

It turns out that a jump over a wider abyss solves this problem, since the trajectory of Mario’s movement changes: he takes on more acceleration and therefore he dodges faster from the fall of Twomp, remaining safe. The jump itself is a little harder for the technique, but in general the test remains as simple. You should pay attention to such things when testing the game, if you apply the IHR principle.

Now apply the same extension to the fireballs:

The test came out harder than with two Twomp, but easier than with fire barriers. The time interval for a successful jump was slightly reduced, but in terms of complexity this example is incomparable with the previous one.

Conclusion: although extensions are easy to apply, their effect is difficult to control. Doubling one element and doubling another is not the same thing, no matter how similar they are.

There are other ways to complicate the test. I call one of them expansion due to compression. It sounds paradoxical, but it perfectly conveys the essence of the reception. Consider an example:

I reduced the distance between Mario and Twomp. This is definitely a quantitative change in the complexity of the very first test and can be considered an extension. But it is achieved by reducing the values. Expansion due to compression almost always implies a reduction in the distance between Mario and the threat, sometimes bringing him closer to her, and sometimes reducing the width of the platform under him. It all depends on the context.

It is most dangerous to overdo it with compression - the player simply will not be able to pass the test without receiving damage. I specifically created such a situation in my last test: an extreme Twomp looms so low above the ground that in any case it hurts Mario when he falls.

Two very important observations about extensions follow from this.

First, there is a limit to the expansion of each element level. Otherwise, the abysses will be too wide, too many enemies, and the safe zones will become too narrow. If you want to find the maximum expansion threshold, it probably makes sense to go from the opposite: start with the maximum difficulty level and move back to simplify it.

Secondly, it is necessary to understand that sometimes extensions complicate testing only at the level of psychology. For example, in the last test of the first 3, Twomp does not really touch Mario if he does not slow down. It turns out that the danger is not so great. If the player thought he had just done something super-complicated and intricate, the level designer did an excellent job with his work.

This is a long and slightly confusing article, so I would like to repeat all the key points. The main idea is this: even though there are clear standards for developing content for levels, they do not make the content completely predictable. And this is very cool - it means that the principle of IHR leaves much room for creativity. It is not needed to make the levels under the stencil, but for the proper organization of content, thanks to which your levels will be organic, interesting and complex.

Nintendo has created several games using this method with minor variations. Moreover, the principle of IMSP (extensions and additions) can be traced in many other games, not only from Nintendo and not only in the platformer genre. Ultimately, it is necessary to organize the content of your game, and not to change its essence.

In the previous lesson, we looked at the concepts of test and modulation. If you have not had the opportunity to get acquainted with the first part, I recommend to do it, otherwise it will be incomprehensible to you. In this tutorial, we’ll talk more about how to use add-ons and extensions.

Although IMSP is a means of organizing content when creating levels, this method in no way limits the creative potential of the designer. I will show you how it can be used to get the maximum effect with a limited set of tools for building levels.

')

My example

I created a demo level that shows how to form a sequence of various trials with varying complexity using a total of 6 different opponents or obstacles. Next, we analyze all the components of this level:

Level ID: 1288 0000 00EC F5A2

Using Add-ons

In the first seven tests of this level, the addition method is used. As you can remember from the first article, the supplemented test is qualitatively more complicated than the previous one, but on the whole retains its idea.

Let's see how it works in this situation. Here is the first test:

We have before us an ordinary Twomp who tries to crush Mario every time he gets too close. The idea is quite simple, and the addition to it is also not difficult.

I added a fire barrier, and now the player must jump over it, instead of just running forward.

Adding one element to another is the most basic form of an add-on. The dynamics are simple: the test becomes more difficult when more obstacles appear in it. But it can also be part of an even more difficult test.

In the following example, I added a new obstacle - the abyss to the left of Twomp.

She doesn’t just force the player to make the jump - she makes him jump right under Twomp’s blow. As you can see, this addition is not much more complicated than the previous one - which is quite normal. Both of these additions are simply branches of the very first test.

Next, I decided to introduce an addition to the abyss: I added a fireball that shoots at regular intervals. Now the player must wait for the right moment to jump over the abyss and dodge Twomp. This also complicates the previous test - however, still not much.

In the following test, I will combine everything that we have used so far:

So far this is the most difficult test: there are 3 obstacles in it at once. In Nintendo games, you rarely find more than three obstacles at a time. This example is really difficult and more or less corresponds to the most difficult trials in games from Nintendo. Of course, you can go further in your game (or in your Mario Maker levels); I am just showing the principle.

In the next two trials, I decided to slightly reduce the complexity and focus on the qualitative changes. Please note: the difficulty levels in the game should not always increase linearly. The complexity may decrease and increase - sometimes it is enough to make the tests diverse, and not more and more difficult.

Given this fact, I removed the chasm and added Chein Chomp instead.

And then I returned the abyss with a ball of fire, but removed the fire barrier.

All these tests are quite complex, but they do not pile up obstacles without stopping. There is a limit to the number of elements added to the test, after which the game ceases to be fun and begins to annoy. But this limit depends on the context.

Use extensions

Before turning to the most important conclusion concerning the supplements, I would like to highlight the correct use of extensions. In the previous article, I defined the extension as an addition, but with quantitative (and not qualitative) changes from the previous test. Consider a simple example:

This is the first extension. We returned to the very first test level and simply doubled the number of Twomp.

What is the relationship between quantitative changes and perceived complexity? Despite the double number of Twomp, the player will hardly make more effort passing it.

Extensions have one important principle: they change the complexity of the test is not linear. Extensions also depend on the context, as well as additions, despite their fundamental differences.

Another example of expansion:

The double number of fire barriers, in contrast to the double number of Twomp, significantly complicates the test (especially due to their asynchronous rotation). In principle, this test can be called the most difficult at all levels. It turns out that we are dealing with exactly the same type of expansion as before, but the experience is completely different.

And what if to apply this reception to other element? For example, to the width of the abyss:

This type of extension is a little harder to recognize. I decided to increase the width of the abyss to two blocks instead of one (that is, double it, like all the elements before), so that the player could feel the difference in the length of the jump, even if he did not immediately see it.

Interesting, but again this slightly increases the difficulty of the test. The fact is that before the player had to select the optimal angle of landing, in order to jump over the abyss, without being hit by Twomp.

It turns out that a jump over a wider abyss solves this problem, since the trajectory of Mario’s movement changes: he takes on more acceleration and therefore he dodges faster from the fall of Twomp, remaining safe. The jump itself is a little harder for the technique, but in general the test remains as simple. You should pay attention to such things when testing the game, if you apply the IHR principle.

Now apply the same extension to the fireballs:

The test came out harder than with two Twomp, but easier than with fire barriers. The time interval for a successful jump was slightly reduced, but in terms of complexity this example is incomparable with the previous one.

Conclusion: although extensions are easy to apply, their effect is difficult to control. Doubling one element and doubling another is not the same thing, no matter how similar they are.

Expansion due to compression

There are other ways to complicate the test. I call one of them expansion due to compression. It sounds paradoxical, but it perfectly conveys the essence of the reception. Consider an example:

I reduced the distance between Mario and Twomp. This is definitely a quantitative change in the complexity of the very first test and can be considered an extension. But it is achieved by reducing the values. Expansion due to compression almost always implies a reduction in the distance between Mario and the threat, sometimes bringing him closer to her, and sometimes reducing the width of the platform under him. It all depends on the context.

It is most dangerous to overdo it with compression - the player simply will not be able to pass the test without receiving damage. I specifically created such a situation in my last test: an extreme Twomp looms so low above the ground that in any case it hurts Mario when he falls.

Two very important observations about extensions follow from this.

First, there is a limit to the expansion of each element level. Otherwise, the abysses will be too wide, too many enemies, and the safe zones will become too narrow. If you want to find the maximum expansion threshold, it probably makes sense to go from the opposite: start with the maximum difficulty level and move back to simplify it.

Secondly, it is necessary to understand that sometimes extensions complicate testing only at the level of psychology. For example, in the last test of the first 3, Twomp does not really touch Mario if he does not slow down. It turns out that the danger is not so great. If the player thought he had just done something super-complicated and intricate, the level designer did an excellent job with his work.

Conclusions and Tips

This is a long and slightly confusing article, so I would like to repeat all the key points. The main idea is this: even though there are clear standards for developing content for levels, they do not make the content completely predictable. And this is very cool - it means that the principle of IHR leaves much room for creativity. It is not needed to make the levels under the stencil, but for the proper organization of content, thanks to which your levels will be organic, interesting and complex.

- A few mechanics are enough to fill the entire level with the right combination of elements. In my level there were only 6 different obstacles, but I did not manage to exhaust all their possibilities.

- Use several different add-ons for your main idea.

- Combine different branches with additions to increase the complexity, but do not overdo them with their number. As a rule, two additions are enough to create an interesting test; if you enter the third, make sure that the game does not become too difficult, and the passage does not require too much time.

- Extensions are quantitative changes, but their effect on the gaming experience may be unexpected. Having doubled any element, you will not increase the complexity of the test exactly 2 times. It can grow by both 10% and 400% - it all depends on what you are expanding.

- There is a limit to the expansion of design elements. If you want to experiment with this limit, practice level design against the opposite: make an impassable difficult level and gradually simplify it until you find a balance.

- Remember: the player’s subjective experience does not depend on how many elements are in your level. If the game was harder than it seemed at first glance, then you, as a designer, did a good job with your work.

Nintendo has created several games using this method with minor variations. Moreover, the principle of IMSP (extensions and additions) can be traced in many other games, not only from Nintendo and not only in the platformer genre. Ultimately, it is necessary to organize the content of your game, and not to change its essence.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/303772/

All Articles