Cybersecurity on endless seas

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the shipping industry for modern society: 90% of goods move precisely by sea. Navigation, like any other large field of activity, develops in parallel with the progress of technical progress: ships are increasing, and teams are decreasing, as more and more processes are being automated. The times when a ship in the sea was actually completely cut off from the rest of the world is a long time in the past. Nowadays, some onboard systems receive updates while sailing, teams have access to the Internet. The issues of cybersecurity of shipping facilities are quite acute.

According to the ENISA report “Analysis of cyber security aspects in the maritime sector” dated November 2011, “the confusion about cybersecurity in the maritime sector is low or non-existent” [1]. CyberKeel, an analyst specializing in the safety of the maritime industry, also notes a minor concern about cyber threats. They note the fact that many employed in the maritime sphere have become accustomed to being part of a “practically invisible” industry, invisible to the common man. “Most often, if an ordinary person does not live near a significant port, he cannot imagine the real scale of the whole industry,” says their report [2]. “Together with the growing reliance on automation, the risk of external interference and disruption of key systems is significantly exacerbated; hackers can interfere with the management of the vessel or the operation of navigation systems, chop off all external communications of the vessel or get hold of confidential data, ”says the Allianz report on the safety of navigation in 2015 [3]. The issue of relevance of the subject matter is further complicated by the fact that, according to Reuters, not all information about successful attacks is widely publicized: business owners can often be silent about it, fearing consequences such as loss of image, claims from customers and insurance companies, began investigations conducted by third-party organizations and government bodies [4].

')

In order to continue the conversation on the cybersecurity of shipping, it is necessary to briefly highlight the information systems and technologies specific to this sphere.

AIS (Automatic Identification System) is an automatic identification system. It is used to transmit identification data of the vessel (including its cargo), information on its condition, current location and course. It is also used to prevent collisions of vessels, monitor their condition, with its help the owner can monitor his ship. Provides communication between the courts. The device works by transmitting signals in the VHF range between ships, floating transponders and onshore AIS gateways that are connected to the Internet. All vessels engaged in international voyages, vessels with a capacity of more than 500 tons of register, and all passenger vessels must be equipped with AIS. The system works on marine search and rescue equipment.

ECDIS (Electronic Chart Display and Information System) is an electronic-cartographic navigation and information system that collects and uses AIS messages, data from radar, GPS and other ship sensors (from gyrocompass) and compares them with stitched maps. It is used for navigation, automation of certain tasks of the navigator and enhancement of navigation safety of navigation. It is worth noting that by 2019 ECDIS must be installed on all vessels. The system is usually a workstation connected to ship sensors and instruments (or two for monitoring and course planning) on which ECDIS software is installed.

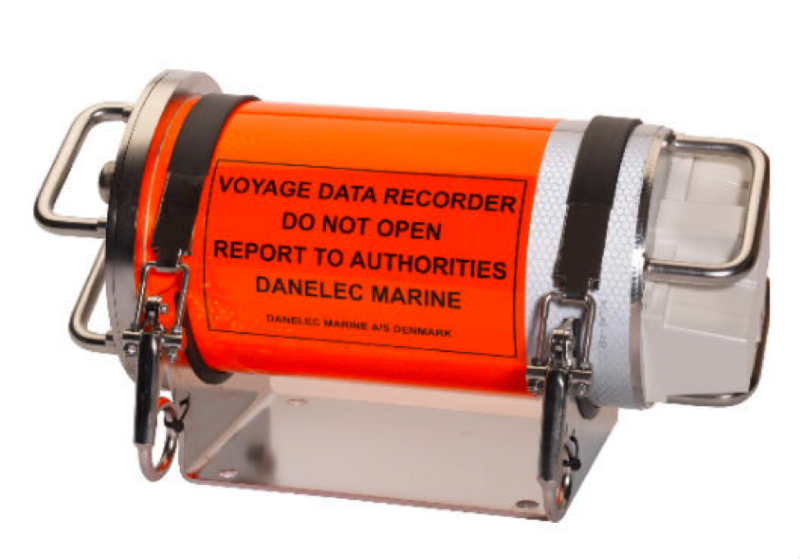

VDR (Voyage Data Recorder) - flight data recorder, flight recorder, analogue of the “black box” used in aviation. The main tasks are recording the vessel’s important voyage information, including both technical and course data, and voice recordings from the captain’s bridge, and its preservation in case of an emergency.

TOS (Terminal Operating System) - IT infrastructure that serves the purpose of automating the processes occurring with cargo in the port - loading and unloading, inventory and monitoring movement through the port area, optimizing storage and finding the right containers at the moment, ensuring further transit. The most complex and heterogeneous item of the list, as in practice it can be both a complete product of a specific vendor and a set of systems (including those for a wide purpose) that perform various tasks.

CTS (Container Tracking System) is a system that allows you to track the movement of containers through GPS and, less commonly, other data transfer channels. Most of the companies involved in this field also offer tracking devices for other areas, for example, personal trackers for tourists, solutions for tracking vehicles, etc.

EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) is an emergency radio beacon, a transmitter that, upon activation, sends a distress signal, the transmission of which, depending on the execution technology, can be carried out via satellite, in the VHF band, or in combination. In addition to the distress signal, some EPIRBs can also transmit vessel information (when synchronized with AIS).

EPIRB beacon

Studies conducted in the past few years, as well as information about incidents, which nevertheless became available to a wide range of individuals, only confirm the concerns about the security of the maritime sector.

Automatic identification system AIS

A large study on the safety of AIS, was conducted by researchers at Trend Micro. The results of the study were presented at the Black Hat Asia 2014 conference [6]. Two attack directions were considered: the first was for AIS providers collecting data from AIS gateways installed on the coasts to collect AIS information and then to provide commercial and free services in real time (for example, MarineTraffic ).

Appearance AIS-device

The second type of attack is at the level of the broadcast, that is, the AIS protocol itself. The attack on the protocol was carried out using SDR (software-defined radio). The protocol architecture was developed quite a long time ago, the mechanisms of validating the sender and encrypting the transmitted data were not provided, since the probability of using expensive “iron” radio equipment to compromise the technology was regarded as low. The study showed the possibility of the following scenarios:

- Changes in ship data, including its location, course, cargo information, speed and name;

- the creation of “ghost ships”, recognized by other ships as a real ship, in any location of the world;

- sending false weather information to specific ships to force them to change course to circumvent a non-existent storm;

- activation of false collision warnings, which may also cause automatic correction of the ship's heading;

- the ability to make an existing ship "invisible";

- creation of non-existent search and rescue helicopters;

- falsifying EPIRB signals that trigger an alarm on nearby vessels;

- the possibility of conducting a DoS attack on the entire system by initiating an increase in the frequency of transmission of AIS messages.

In addition, it is worth noting that ship personnel can turn off their AIS, becoming “invisible” (according to CyberKeel, quite common practice for passing dangerous areas of the water area, such as the Gulf of Aden, the “fiefdom” of Somali pirates) and in some cases changing the broadcast information manually.

Drawing a non-existent warship of country A on AIS maps in the territorial waters of country B could provoke a diplomatic conflict. In addition, an attacker could also cause the vessel to deviate from its course due to the substitution of reports of a possible collision with it or to “lure” to a certain point in the water area by creating a false alarm beacon signal.

Navigation system ECDIS

On 3 March 2014, the NCC Group released a report on the security of ECDIS systems. The report presented the results of a study of one of the leading vendors (the name is not indicated in the report) [7]. It is noted that most systems of this class are a set of applications installed on a workstation running Windows OS (often XP) and located on the bridge of the vessel. To the workstation with ECDIS, by means of the on-board LAN network, from which most often there is access to the Internet, other systems are connected: NAVTEX (navigation telex, unified system for transmitting navigation, meteorological and other line information), AIS, radar and GPS equipment, as well as other sensors and sensors.

ECDIS system interface

Complete with ECDIS-systems usually do not come with any means of information protection. It is also worth noting that Windows systems deployed on ships that have been on cruise for a long time do not always have time to receive even critical security updates within a reasonable time. Vulnerabilities found by researchers from the NCC are mainly related to the Apache server installed in conjunction with the system. A malicious code can be implemented either by an external intruder via the Internet, or by a member of the team through physical media used to update or supplement navigation maps. The found vulnerabilities allowed to read, download, move, replace and delete any files located on the workstation. With this development, the attacker gets access to reading and changing data from all service devices connected to the ship’s on-board network.

The correct operation of the ECDIS system is very important, its compromise can lead to the most adverse consequences - injuries and even death of people, pollution of the environment and large economic losses. A ship is “frozen”, having lost the ability to navigate correctly, will block a busy canal or gateway for an indefinite period, which will cause, under certain circumstances, enormous economic losses. A tanker carrying oil or other chemical products and stranded due to navigational errors is a ready-made scenario for an environmental disaster.

VDR Flight Data Recorder

As mentioned above, the VDR is an analogue of the aircraft "black box". The data obtained from the device is extremely important in the investigation of incidents, accidents and catastrophes that occurred at sea.

It looks like a VDR

On February 15, 2012, the Marines on board the Italian private tanker Enrica Lexie, whose task was to protect the vessel from a possible attack by pirates, mistakenly opened fire on an Indian fishing vessel and killed two Indian citizens. From the onboard recorder of the tanker, data from the sensors and voice recordings disappeared during the period of time when the incident occurred [9]. Two versions of the cause of what happened were called: overwriting the data by the VDR itself and intentionally destroying evidence. The loss of data naturally complicated the investigation, which gave rise to the diplomatic conflict between India and Italy and ended only on August 24, 2015.

A couple of weeks after the events at Enrica Lexie, the first of May 2012, a Singapore-owned Prabhu Daya cargo truck rammed a fishing boat in the coastal waters of India, in the Kerala region, and fled the scene. As a result of the collision, three fishermen were killed. After the Indian law enforcement agencies launched an investigation, an interesting detail surfaced in the press: “When officials arrived at the Singapore vessel, one of the members inserted a USB stick into the VDR; this led to erasing all files and voice recordings from it. Later, despite all the efforts of the experts, the data could not be recovered ”[9].

The manufacturer of the VDR recorder installed on the Italian ship Enrica Lexie was Furino. Later, one of the devices of this company (VDR-3000 recorder) was investigated by IOActive employees. The device under study consisted of two modules: DCU (Data Collection Unit) and DRU (Data Recording Unit). The DCU module was a Linux-machine with a set of interfaces (USB, IEEE1394 and LAN) for connecting to ship sensors, sensors and other systems, as well as equipped with HDD with a partial copy of the data of the second module. Inside the DRU module, protected from aggressive external influences, there was a stack of flash disks designed to record data for a 12-hour period. The device collected and stored all sorts of navigation and statistical data of the vessel, sound recordings of conversations on the bridge of the vessel, all radio communications and radar images. Following the results of the work, such opportunities as changing and deleting data from both the DCU disk and DRU, as well as the ability to remotely execute commands with superuser privileges, which completely compromises this device, were demonstrated [10].

The cases of Enrica Lexie and Prabhu Daya clearly indicate that deleting data on a VDR can make it extremely difficult, or completely deadlocked, to investigate an incident at sea. Moreover, if the attackers have the ability to edit data on the recorder and their replacement, there is a high probability of fraud, which will lead the investigation into a false path.

TOS and other port systems

Port information systems are undoubtedly the most complex and extensive IT structures in shipping. “If you saw one port - you saw one port” is a common phrase, because each port as a whole and from the point of view of information systems is unique. However, it says a lot that extremely little attention is paid to port cybersecurity.

TOS operator at work

US Coast Guard Commander Joseph Krameck, in a monograph on cyber security of major US ports, writes: “Of the six ports that have been verified, only one has carried out a cybersecurity risk assessment; no port had an incident response plan in this area. Moreover, out of the $ 2.6 billion allocated under the program of grants to protect ports created after the events of September 11, 2001, less than 6 million were spent on projects related to cybersecurity ”[11]. Other risk factors noted by the author are the maintenance of some systems by companies that are not related to the port, the work of employees from their devices, the lack of cybersecurity training among personnel.

The most famous port cybersecurity incident occurred in the port of Antwerp in 2012 [12]. A brief scheme according to which smuggling was delivered to Europe was as follows: smuggled goods (mainly drugs and weapons) were loaded into containers in which registered and properly decorated goods arrived from Latin America were transported. Upon arrival in Europe, the IT department of the gang intercepted the 9-digit PIN codes used to conduct operations with containers in DP World systems. These codes are necessary for operations with port loading-unloading systems. After the smuggling container arrived in Antwerp, smugglers connected to one of the port wireless networks gave the command to the loading systems to move the “charged” container to their truck before the owner arrived. Operational work, which began after company complaints about the periodic loss of containers, led to a series of searches and raids in Denmark, the Netherlands and Belgium. Weapons, cash and cocaine were found, fifteen people were detained. It's funny that a similar technological approach to smuggling appeared in popular culture several years before the events in Antwerp: in the second season of the TV series The Wire, the story develops around the American port of Baltimore (according to the plot of one of the series, the criminals bribe working docks to replace records of containers in which drugs are transported). Jim Girmansky, a former FBI agent, now chairman of Powers International, a security and monitoring logistics company, said that he was not surprised by the “Antwerp” business, because most transport companies have no idea how to protect container [13].

Image: Bloomberg

According to the latest estimates, more than 420 million containers are transported annually by sea, and only 2% are subject to inspection and inspection, so that it is difficult even to speculate about the actual volumes of smuggling even in “legal” containers. In addition to drug traffickers and smugglers, terrorist and radical groups may also benefit from security holes in port and other logistics systems, for example, organizing the delivery of explosive devices to the desired city and, possibly, at another's expense.

CTS, GPS and satellite systems

The maritime industry is actively using satellite technology SATCOM (Satellite Communications) to access the Internet, ship-to-ship and ship-to-land communications, GPS / DGPS for positioning and navigation, as well as tracking of goods transported.

At the Black Hat USA 2015 conference, Synack researcher Colby Moore presented the Globalstar GPS tracking systems security report [14]. In addition to commercial freight, the solutions offered by the company are also used in the mining industry, environmental monitoring systems, the car industry, small boats and many other areas. The study showed that the exploitation of the found vulnerabilities leads to the interception and substitution of information or jamming of the signal.

As in the case of AIS, the disclosure of the Globalstar problem became possible due to the development of SDR technologies, their relative simplicity and low cost. The Simplex network, based on the radio transmission used by Globalstar to transfer data between trackers, satellites and ground stations, lacks authentication and encryption mechanisms serving the systems, and the data transfer mechanism working only in one direction does not represent the possibility of validating the transmitted data. Moore is confident that this problem is not only present in Globalstar [15].

Satellite communication systems (SATCOM), including ships connected via the Internet to each other and to the “mainland”, also contain a large number of vulnerabilities, according to an IOActive report [16]. Inspection of satellite communications terminals used in shipping and in other sectors (aviation, military complex) and produced by leading companies in the industry (Harris, Hughes, Cobham, JRC, Iridium) revealed critical security holes such as devices using unprotected or even undocumented protocols. “factory-made” accounts, the ability to exploit the password reset function, backdoors. However, all confidential information obtained during inspections and research, including technical aspects and procedures for conducting inspections, as well as information on exploitation opportunities for vulnerabilities, after being transferred to vendors and regulatory commissions, was not made publicly available.

Another significant case of satellite systems compromise occurred in July 2013. Students from the University of Texas at Austin were able to deviate a yacht worth $ 80 million from the course using equipment whose price did not exceed $ 3,000. Using a GPS signal simulator (used, for example, when calibrating equipment) duplicating the signal of a real satellite and gradually increasing the power, they managed to “convince” the ship’s navigation system to receive messages from the spoofing device and to discard the signal of a real satellite as interference. After the navigation system began to navigate according to the data of two satellites and an attacking device, the researchers managed to divert the vessel from the original course [17].

In conclusion, it is possible to say that poorly preparedness is so important for any country in the industry for times when cyber attacks are no longer something new and are widely used in their own interests by the state and various activist, criminal and terrorist groups. In addition to software vulnerabilities and other security holes in these systems, there is also an acute problem of the inability to instantly apply security updates to systems on ships that are in voyage or remote ports. One can only hope that the above problems will not turn the sea transportation into a “time bomb” and the large-scale work to correct the problems and “hardening” of the considered systems will begin before serious precedents appear.

List of sources:

- Analysis of cyber security aspects in the maritime sector , ENISA, 10.2011.

- Maritime Cyber-Risks , CyberKeel, 10/15/2014.

- Safety and Shipping Review 2015 , H. Kidston, T. Chamberlain, C. Fields, G. Double, Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, 2015.

- All at sea: global shipping fleet exposed to hacking threat , J. Wagstaff, Reuters, 04/23/2014.

- MARIS ECDIS900 , MARIS brochure.

- AIS Exposed: Understanding Vulnerabilities & Attacks 2.0 ( video ), Dr. M. Balduzzi, Black Hat Asia 2014.

- Preparing for Cyber Battleships - Electronic Chart Display and Information System Security , Yevgen Dyryavyy, NCC Group, 03/03/2014.

- Daya's Voyage Data Recorder of Prabhu may have been tampered with , N. Anand, The Hindu, 11.03.2012.

- Lost voice data recorder for cost indians. Italian marines case , A. Janardhanan, The Times of India, 13.3.2013.

- Maritime Security: Hacking into a Voyage Data Recorder (VDR) , R. Samanta, IOActive Labs, 01/09/2015.

- The Critical Infrastructure Gap: US Office Buildings, Comdr (USCG) J. Kramek, Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at Brookings, 07.2013.

- The Mob's IT Department: How two technology consultants helped the drug traffickers hack the Port of Antwerp , J. Robertson, M. Riley, Bloomberg Businessweek, 07.07.2015.

- To Move Drugs, Traffickers Are Hacking Shipping Containers , A. Pasternack, Motherboard, 10/21/2013.

- Spread Spectrum Satcom Hacking: Attacking the Globalstar Simplex Data Service , C. Moore, Black Hat USA 2015.

- Hackers Could Heist Semis by Exploiting This Satellite Flaw , K. Zetter, Wired, 07/30/15.

- A Wake-Up Call for SATCOM Security , R. Santamarta, IOActive, 09.2014.

- University of Texas team takes on GPS GPS , B. Dodson, gizmag, 08/11/2013.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/303198/

All Articles